Jet lag

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| F51.2 | Inorganic disruption of the sleep-wake cycle |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

As jet lag (from the English by jet , jet 'and was , time difference') is one after long-haul flights over several time zones of the sleep-wake rhythm occurring disorder (circadian dysrhythmia - circadian rhythm ), respectively. As a German transmission, it is sometimes referred to as the time zone hangover.

According to the classification system for sleep disorders " International Classification of Sleep Disorders " (ICSD-2), jetlag belongs to the circadian sleep-wake rhythm disorders and is referred to in this context as "circadian sleep-wake rhythm disorder, type jetlag".

After traveling quickly across several time zones, the internal clock is no longer in sync with the new local time . Light and darkness appear at unusual times; the natural rhythms like eating and sleeping times, hormone production or body temperature are out of step. Since the internal clock cannot adjust to a new local time in the short term, various physical and psychological complaints develop. Prevention and treatment are used in particular with behavioral recommendations that make it easier to adapt to the time zone of the destination.

complaints

The most common complaints of jet lag are sleep disorders in the form of difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep , fatigue, dizziness, mood swings, loss of appetite and reduced performance with physical, manual and cognitive demands. The subjective complaints usually disappear after a few days, while objectively measurable parameters in the sleep laboratory , body temperature and hormone status only adapt after a long time (up to two weeks). Although almost all travelers experience complaints with a time difference of more than five hours, their severity and recovery from them vary greatly from person to person. Even if the influence of many factors has not been systematically investigated, the symptoms seem to be more pronounced with older age.

Influence of the flight direction

The direction of flight has an influence on the extent of jetlag, although this is usually felt more strongly when traveling by air to the east. For many people, it is easier to stay up late in the evening than to get up earlier in the morning. Flights to the east require accelerated, i.e. shortened, clock phases (corresponds to an early sunrise or sunset and thus getting up earlier) , flights to the west, on the other hand, require longer clock phases (corresponds to a delayed sunrise or sunset and thus longer staying up) .

|

Example 1: Eight time zones

westward from Frankfurt am Main to Denver

|

Example 2: Eight time zones

eastwards from Munich to Seoul

|

After the westward flight shown in the table, it is as if you had stayed up all night and only went to bed at 6 a.m., eight hours later than normal. After the illustrated flight eastwards, it is as if one had also stayed awake the night, but only went to bed at 2 p.m., 16 hours later than usual.

Basics

The aim of the research is to gain an understanding of the mechanisms underlying jet lag. For methodological reasons, animal experiments are primarily available.

Circadian rhythm

The most important timer in humans is the light-dark rhythm of the times of day. The mechanisms on which this is based have remained remarkably stable during evolution and typically consist of self-regulating cycles in which specific proteins (so-called “clock proteins”) control their own gene expressions . Such regulations maintain the 24 hour cycle of RNA and protein expression . Despite the retention of these mechanisms, questions have been raised about their relevance, whereupon it has been shown that the oscillation of important “clock” genes can be eliminated without the loss of the basic internal clock. Already at the beginning of the 1970s, Seymour Benzer was able to document different timelines of the circadian rhythm in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster .

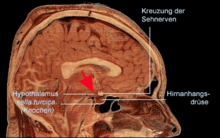

Internal clock (mammals including humans)

In mammals, the circadian rhythm is determined by an internal clock, which is located in a part of the hypothalamus , the nucleus suprachiasmaticus . The circadian rhythm influences numerous body functions, such as body temperature, blood pressure, urine production and hormone secretion, and could also be detected in individual cells. The internal clock usually does not run exactly every 24 hours. Under normal, constant conditions, it is influenced daily by exogenous timers (e.g. living conditions, time of meals and bright light); so it stays in sync under normal circumstances. These timers are also important in readjustment in the event of jet lag, in which melatonin is also involved. This is increased in the dark and in bright light - z. B. Daylight - less released. The most important timer in humans is the light-dark rhythm of the times of day. The circadian rhythm changes only slowly, so that it is not changed abruptly despite a one-time disturbance of the night's rest.

Basic research on the animal model

Although jet lag is very common these days, few high-level studies have looked at it. Shift work and frequent jet lag reduce mental performance and increase the risk of health problems. Examples of this are digestive problems, stomach ulcers , sleep disorders and cancer . Some of these problems increase over the years as a result of the aging process or an accumulation (accumulation) of damage. The morbidity rate also naturally increases over the years; However, what role the internal clock plays in this is largely not understood.

When a mammal is exposed to bright light and this information is passed on to the suprachiasmatic nucleus , glutamate and PACAP (pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide) are released, which reach the nerve cells ( neurons ) there and cause the internal clock to change. Light in the early night phase delays and light in the late phase accelerates this adjustment. In both cases, the intracellular calcium ion level and the activity of some enzymes such as phosphatases and kinases (including the mitogen-activated protein kinases and the Ca 2+ / calmodulin-dependent protein kinase) increase. This process depends on CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein) and ELK-1 (member of ETS oncogene family) and the "clock genes" (CLOCK for Circadian Locomotor Output Cycles Kaput ). In contrast to these nocturnal processes, animals also react to stimuli such as saline injections, involuntary activities in a new environment, or even darkness during the day. The cAMP / PKA metabolic pathway is involved in these cases , and the administration of cAMP analogues then accelerates the phase sequence. In addition, there are indications that the cAMP / PKA metabolic pathway also plays a role at night. It seems to support the effects of the above-mentioned glutamate and PACAP release in the early hours of the night and counteract them in the late hours.

In hamsters that are active at night and at dusk , the mechanism responsible for light-induced phase forerunners includes glutamate, Ca 2+ / calmodulin-dependent protein kinase and neuronal NO synthase , which in turn influence the “clock genes”. This influence takes place differently in the early and late hours of the night. In the late hours of the night, it leads to the activation of guanylyl cyclase - cGMP -dependent protein kinase (PKG-cGMP-dependent protein kinase) , which in turn accelerates the phases. In hamsters, the cGMP level in the suprachiasmatic nucleus is highest during the day. The change appears to be related to the cGMP phosphodiesterase activity and not to that of guanylyl cyclase. With light stimulation in the late hours of the night, the cGMP level increases significantly, but not with the same stimulation in the early hours of the night, from which it can be deduced that it leads to a phase acceleration and not a phase delay. cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitors , which prevent the hydrolysis of cGMP, allow this substance to accumulate in the cell. Sildenafil prevents the influence of phosphodiesterase-5 on the cGMP and extends and increases the effect of the NO synthase / cGMP metabolic pathway described above. The cGMP level is of particular importance for the accelerated phase shift of the internal clock.

Prevention and treatment

For the prevention and treatment of jet lag, there are a large number of behavioral recommendations aimed at making it easier to adapt to the time zone of the destination and thus alleviating the symptoms of jet lag. In the case of short stays at the destination, however, it can also be considered, contrary to the reality found, to maintain the day-night rhythm of home.

General recommendations for behavior

The following behavioral recommendations are based in most cases on experience and have not been proven by medical studies.

- Set the clock to the time of the destination country while on the plane in order to mentally get used to the new time rhythm

- participate in the daily rhythm of the destination

- spend a lot of time outdoors at the destination

- ensure adequate sleep the first night after arriving at your destination

- avoid strenuous activity for the first two days after landing

- do not take sleeping pills or alcohol

Influence of light

In analogy to the basics found on the animal model, it is known from laboratory studies, but only from a few field tests , that the time of exposure to bright light - based on the phase of the lowest core body temperature (3 to 5 a.m. of the felt time) - has a particular influence has to adapt to a time change. If bright light has an effect in the six hours before, it delays the change, in the six hours after it it promotes it. When flying eastwards from up to nine time zones, the goal must be to adjust the internal clock by exposure to light in the six hours after the body temperature has reached its minimum. At the same time, such light exposure should be avoided beforehand, as it delays the changeover. Converted into hours this means that you should expose yourself to bright light after 5 a.m. and avoid it before 3 a.m. (based on the felt time, not local time). For all flights to the west and over more than nine time zones to the east, however, the aim should be to delay the changeover by exposing yourself to bright light in the six hours before 3 a.m. and avoiding it in the six hours after 5 a.m. So if you live there according to your usual habits analogous to local time on a flight to the west, this is in accordance with these rules, but not on a flight to the east. This concept explains the often described feeling that trips to the west are better tolerated than trips to the east. Battery-operated “light glasses” and corresponding tables for travelers have been developed to help implement this concept. These principles can also be used preventively.

Melatonin supplements

The widely touted use of melatonin supplements to relieve jet lag remains controversial. Although a meta-analysis of several clinical studies indicated that melatonin can be effective in a dose of 0.5–5 mg, another meta-analysis questions the effectiveness of melatonin and also sheds light on the problem of possible drug interactions (e.g. . Antithrombotic drugs and anti-epileptics).

Medication

The intake of medication must be adapted to the new daily rhythm. This is particularly relevant for some hormone preparations such as B. Insulin or the mini pill . Before traveling across several time zones, you should therefore seek medical advice from a suitably trained doctor or pharmacist .

nutrition

Sufficient fluid intake during the flight can prevent dehydration and thus improve well-being after the flight, regardless of jet lag syndrome. Further studies will have to confirm whether a special diet actually has a positive effect on jet lag symptoms; current studies seem to confirm this influence.

Origin of the term

Historically, the worldwide spread of the term “jetlag” (in the sense used today) goes back to the work of Charles Ehret (American chronobiologist, 1923–2007). Through his book Overcoming Jet Lag , published in 1983 together with Lynne Waller , the term first came to the general public. The book has sold over 200,000 copies. It caught the attention not only of musicians, athletes, businessmen, diplomats and shift workers, but also of the American President Ronald Reagan and the military.

In the Anglo-American literature, however, the term appeared before 1983. It can be proven as early as the mid-1960s on the rainbow pages of the press. More or less ironically, it was referred to as one of the chic new ailments (“one of the chic new diseases”) or used as an alliteration to jet set .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Time zone hangover in Beolingus

- ↑ S3 guideline for non-restful sleep / sleep disorders of the German Society for Sleep Research and Sleep Medicine (DGSM). In: AWMF online (as of 2009)

- ^ A b c Paulson: Travel statement on jet lag. In: CMAJ. 1996, 155 (1), pp. 61-66. PMID 1487871 .

- ^ A b c J. Waterhouse: Jet-lag and shift work: (1). Circadian rhythms. In: JR Soc Med. August 1999, 92 (8), pp. 398-401. PMC 1297314 (free full text)

- ^ Waterhouse et al.: Identifying some determinants of “jet lag” and its symptoms: a study of athletes and other travelers. In: Br J Sports Med. 2002, 36 (1), pp. 54-60. PMID 11867494

- ↑ Ariznavarreta et al .: Circadian rhythms in airline pilots submitted to long-haul transmeridian flights. In: Aviat Space Environ Med. 2002, 73 (5), pp. 445-455. PMID 12014603

- ^ Xiangzhong Zheng, Amita Sehgal: Probing the Relative Importance of Molecular Oscillations in the Circadian Clock. In: Genetics. March 2008, 178 (3), pp. 1147-1155. doi: 10.1534 / genetics.107.088658 . PMC 2278066 (free full text)

- ↑ Russell Van Gelder: Timeless genes and jetlag. In: Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006, 103 (47), pp. 17583-17584. doi: 10.1073 / pnas.0608751103 . PMID 1693787

- ↑ a b A. J. Davidson, MT Sellix, J. Daniel, S. Yamazaki, M. Menaker, GD Block: Chronic Jet-lag Increases Mortality in Aged Mice. In: Curr Biol. November 7, 2006, 16 (21), pp. R914-R916. doi: 10.1016 / j.cub.2006.09.058 . PMC 1635966 (free full text)

- ↑ LJ Ptácek: Novel insights from genetic and molecular characterization of the human clock. In: Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2007, pp. 273-277. PMID 18419283

- ↑ a b Patricia V. Agostino, Santiago A. Plano, Diego A. Golombek: Sildenafil accelerates reentrainment of circadian rhythms after advancing light schedules . In: PNAS. June 5, 2007, Volume 104, No. 23, pp. 9834-9839.

- ↑ CS Colwell: NMDA-evoked calcium transients and currents in the suprachiasmatic nucleus: gating by the circadian system . In: European Journal of Neuroscience. Volume 13, Issue 7, pp. 1420-1428. doi : 10.1046 / j.0953-816x.2001.01517.x , PMID 11298803 , PMC 2577309 (free full text).

- ↑ N. Mrosovsky: Locomotor activity and non-photic influences on circadian clocks. In: Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. Volume 71 August 1996, pp. 343-372. PMID 8761159 .

- ^ Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT): Travel Statement on Jet Lag . In: Canada Communicable Disease Report. Volume 29. ACS-3, April 1, 2003.

- ^ I. Charmane: Advancing Circadian Rhythms Before Eastward Flight: A Strategy to Prevent or Reduce Jetlag In: Sleep. January 1, 2005, 28 (1), pp. 33-44. PMC 1249488 (free full text)

- ^ J. Arendt: Does melatonin improve sleep? In: BMJ. 2006, 332, p. 550 (March 4th), doi: 10.1136 / bmj.332.7540.550

- ↑ A. Herxheimer, KJ Petrie: Melatonin for the prevention and treatment of jet lag. In: Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1, p. CD001520, 2001.

- ↑ Buscemi et al .: Efficacy and safety of exogenous melatonin for secondary sleep disorders and sleep disorders accompanying sleep restriction: meta-analysis. In: British Medical Journal. Volume 332, 2006, pp. 385-393. PMID 16473858

- ^ NC Reynolds, R. Montgomery: Using the Argonne diet in jet lag prevention: deployment of troops across nine time zones. In: Mil Med. 2002, 167 (6), pp. 451-453. PMID 12099077

- ^ PM Fuller, J. Lu, CB Saper: Differential Rescue of Light- and Food-Entrainable Circadian Rhythms. In: Science. 320, 2008, pp. 1074-1077, doi: 10.1126 / science.1153277 .

- ↑ Patricia Sullivan: Charles F. Ehret; Devised Method to Fight Jet Lag . In: Washington Post. March 4, 2007, p. C07.

- ^ DA Rockwell: The "Jet Lag" syndrome. In: West J Med. 122 (5). May 1975, p. 419 PMC 1129759 (free full text)

- ^ E. Sheppard (Women's Feature Editor): A Case of Jet Lag. In: New York Herald Tribune . Inside Fashion rubric , February 23, 1965, p. 21, column 3 (online) ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Los Angeles Times , article by H. Sutton dated February 13, 1966. In: R. Maksel: When did the term "jet lag" come into use? Air & Space / Smithsonian Magazine, June 18, 2008.