Xueta

The Xuetas , in Catalan xuetes [ ʃwətəs ], are a social group on the Spanish island of Mallorca . They are descendants of the Mallorcan Jews who converted to Christianity . Throughout the period since converting to Christianity, they have acquired a collective awareness of their ancestry. Because they have one of the surnames of converted families who were persecuted by the Inquisition for “secretly practicing the Jewish faith” in the last quarter of the 17th century. Historically, they have been stigmatized and have had to live in isolation. Until the middle of the 20th century, families only got married within the group. Today around 18,000 to 20,000 people in Mallorca have one of the Xueta surnames.

Etymology and other designations

The term xueta appeared for the first time in connection with the first inquisition trials in 1688 as a common expression for the accused. Its etymology is controversial and various hypotheses exist. The most common are:

- The term comes from the Catalan word juetó , the diminutive of jueu (Jew), which changed to xuetó - a term that is still in use - only to develop into xueta . The main argument in support of this hypothesis is that its original use is self-explanatory, which precludes condescending connotations.

- For others it is a disparaging expression that comes from the word xulla (bacon or pork in general, in Mallorcan it is pronounced xuia or xua [ ʃwə ]). This term would refer to the eating habits of the converted Christians with regard to pork or to the tradition of different cultures to name Jews and converts with insulting words that are in connection with pigs - see also Marranen .

- A third hypothesis connects both etymologies: the word xuia is said to have provoked the replacement of the letter j from juetó by the letter x , so that xuetó was created. And for its part, xueta prevailed instead of xuetó due to its higher phonetic similarity to xuia .

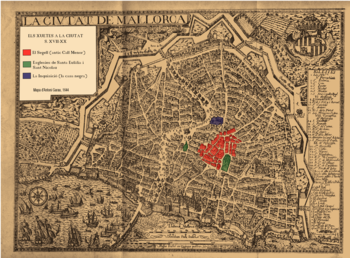

In addition, the Xuetas were also called del carrer del Segell (from the Segell street) because of the name of the neighborhood in which the majority of them lived. In addition, there is the name del carrer , which on the one hand is an abbreviation of the just mentioned expression del carrer del Segell , on the other hand it can be derived from the Castilian de la calle , an internal name for the Xuetas in the official documents from the Inquisition period, due to their phonetic proximity to the expression del call , which refers to the old Jewish quarter in Palma de Mallorca. Recently, the Xuetas have been associated with Argenteria Street . This now represents the Jewish street with the most Jewish inhabitants in Palma until recently. Its name goes back to one of the most characteristic buildings of the group.

In some documents the terms hebreo , genero hebreorum , estirpe hebrea , direkt jueus or also the Castilian judío [ ʒodío ], macabeos or in connection with their usual professions argenters (jeweler) and marxandos (grocer and peddler) were used.

What is certain is that the term xueta developed into an insulting expression after the Inquisition trials . Those affected themselves used more neutral terms such as del Segell , del carrer . The most common was noltros (we) or es nostros (our) as a counterpart to ets altres (the others) and es de fora del carrer (those from outside the street).

Surname

The Xueta surnames are: Aguiló, Bonnín, Cortès, Fortesa / Forteza, Fuster, Martí, Miró, Picó, Pinya, Pomar, Segura, Tarongí, Valentí, Valleriola and Valls. These come from very large converted congregations, as the registers of religious conversions between the 14th and 15th centuries and those of the Inquisition in Mallorca at the end of the 15th and beginning of the 16th centuries document more than 330 converts who were punished for their Jewish faith. It attracted the attention of many researchers in this field that some Mallorcans clearly have Jewish surnames, but have neither Hebrew nor Jewish ancestors (for example: Abraham, Amar, Bofill, Bonet, Daviu, Duran, Homar, Jordà, Maimó, Salom, Vidal and others).

Having a converted ancestor is not enough to be xueta ; this descent must have established itself in the common memory of the Mallorcans through the identification of families and lineages. Therefore only some of the converted descendants are really Xuetas, although the Xuetas are all descendants of converted people.

genetics

Various studies by the Departamente de Genética Humana of the University of the Balearic Islands confirmed that the Xuetas form a homogeneous group from a genetic point of view. With regard to the analysis of the Y chromosome on the paternal side and the mitochondrial ADN on the maternal side, they are related to the Jewish population in the Orient, but also to the East and Central European Jews and those in North Africa.

They can also have some pathologies of genetic origin, such as the familial Mediterranean fever , which they have in common with the Sephardic Jews.

history

ancestors

Converted Jews (1391–1488)

Until the end of the 14th century, the Mallorcan Church put great effort into converting the Jews. But the success was only of anecdotal character and had no consequences for the social structure of the population. This situation changed from 1391 with the attack on the Jewish quarters, the sermons of San Vicente Ferrer in 1413 and the conversion of the rest of the Jewish community on Mallorca in 1435. These events represented a risk and a danger to the community, which is why mass conversions were carried out, which led to the emergence of the converts social phenomenon.

Because conversions were forced, many new converts simply continued to practice their traditional religious practices. As a result, the Cofradía de Nuestra Señora de Gracia or de Sant Miquel dels Conversos was founded to replace the old Jewish congregation, which had supported the group in various areas of life, such as internal justice, marital union and, of course, religious cohesion.

Until the last quarter of the 15th century, converts were able to carry out their activities, albeit partly secretly, without any particular social or state pressure, because there was little inquisition activity and there were no rules for a separation of faith. It was probably because a relatively large group of the converts remained intact.

Beginning of the Spanish Inquisition (1488–1544)

In 1488, when some of the last converts from 1435 were still alive, the first inquisitors of the new Tribunal of Catholic Kings , who were in the process of establishing a nation-state based on a unified religion, came to Mallorca. As in all areas of the Aragonese rule, there was no lack of protest and a fundamental defensive stance against it, which was of little use. The main goal was the suppression of secret Judaism. It began with the introduction of a pardon order, which meant that if you reported yourself for heresy , you could avoid severe conviction.

Because of this pardon decree (1488–1492) 559 Mallorcan Jews reported themselves, with the Inquisition the names of the majority of the Jews living on Mallorca fell into the hands. Entire families and kinship groups were severely punished. In retrospect and up to 1544, 239 defendants were waived their sentences as Jews who were supposedly disguised. Of the remaining 537 accused, 82 were executed and cremated and 455 fled, which is why only one statue of them was burned.

New game of hide and seek (1545–1673)

This period is characterized by the reduction in the group due to fleeing the punishment of the previous epoch and because the majority of those who remained converted to Catholicism . At the same time, the statutes of the Limpieza de sangre began to expand in a large part of the organizations of the Catholic Church and religious orders. Even so, a small group of the large community of converted Mallorcans persevered and concentrated in a few streets. They were in some way integrated into the Catholic church organization and in special trading communities, had a pronounced and complex endogamy, and secretly practiced their Jewish faith.

During this period, the Inquisition in Mallorca ceased to act against Jews, although they knew of prohibited activities. The following reasons are possible: the adoption of the structure of the Inquisition in the internal Mallorcan parties, the emergence of new religious phenomena such as conversions to Islam and Protestantism or the control of the morality of the clergy . But there is no doubt that the secret Jews use more efficient strategies for their own protection. The later inquisition processes inform that the transition to religious practices did not take place until adolescence and for women only when it was clear who they were Husband would be and what faith he practiced.

In this context, the lead Mallorcan inquisition official Juan de Fontamar sent a report to the Supreme Inquisition Authority in 1632, in which he listed 33 cases of secret Judaism. These included, for example, the prohibition of marrying old Catholics and, in the event of violation, social rejection; secret exercise of Judaism; the arrangement of marriages; the sole possession of the Old Testament in the house without owning the New Testament ; Contempt and abuse of Christians; exercising weight-related occupations to deceive Christians; gaining positions within the Catholic Church in order to make fun of them after impunity; Introduction of a separate legal system; Making collections for the poor; Financing a synagogue in Rome , where they had a representative; secret gatherings; Jewish practices such as B. Consecration and fasting; Keeping the sabbath ; Avoidance of religious practices in the event of death; and finally the performance of human sacrificial rituals. Surprisingly, the Inquisition did not intervene in this case.

Around 1640, the descendants of the converts began a strong economic rise and they gained increasing influence on the trading world. Before that, with a few exceptions, they were primarily artisans and grocers. From then on, however, and for little apparent reasons, some of them began to emerge in other branches of the economy: they set up complex trading companies, participated in foreign trade (they managed to control 36% of it), they dominated the insurance market and distribution of imported products. On the other hand, usually only converts had a part in the companies and these determined part of the income for charitable purposes, which flowed directly to the population, while the rest of the population was used to donating through the church.

Because of the immense economic activity abroad, they re-established contact with the Jewish communities around the world, particularly Livorno , Rome , Marseille and Amsterdam . Through these contacts they had access to Jewish literature. It is known that Rafel Valls, the religious leader of the converted Mallorcans, traveled to Alexandria and Esmirna during the epoch of the false messiah Shabbtai Zvi , although it is not known whether he had any contact with him.

It is likely that a system of internal social camps was formed during this period - although it is also said to date from an earlier Jewish era - that distinguished a kind of aristocracy from the rest of the group. Later these were called orella alta or orella baixa . There should have been distinctions according to religion, occupation and kinship, which led to a kind of umbrella association and the avoidance of cross-surnames and at that time had a great influence on endogamous practices.

genesis

Second persecution (1673–1695)

The reasons for the resumption of the persecution of Mallorcan Jews after around 130 years and that at a time when the inquisition activities were already declining are not entirely clear: the Crown's financial crisis, the concern about decayed, economic sectors in addition to the economically dynamic rise of the Converts, the resumption of religious practices in the community instead of restrictions on the domestic 4 walls, a resurgence of religious fervor and the judgment against Alonso López could be among the motivations.

The clues

Up to the year 1670 concrete references to Mallorcan converts like these are very rare, but from this point on they appear increasingly in the writings of the Catholic Church, the tax office and the Inquisition. This suggests a general perception of the group's existence. Some of them announced the mobilization activities by the Inquisition:

In July 1672 a merchant informed the Inquisition that some Jews from Livorno had asked him for information about Mallorcan Jews named Forteses, Aguilóns, Tarongins, Cortesos, Picons, etc. In 1673 a ship with a group of Jews displaced by the Spanish Crown stopped for Livorno on Mallorca. The Inquisition arrested a young man called Isaac López who was 17 years old and who was born in Madrid and baptized Alonso. He fled as a child with his converted parents. Alonso refused to repent and was eventually burned alive in 1675. His execution aroused strong sympathy among the Jews and at the same time aroused great admiration for his resilience and courage. In the same year that López was arrested, some young converts informed their confessor of their spied knowledge about Jewish ceremonies that their employers held.

The Conspiracy

In 1677, four years late, the supreme authority of the Inquisition decreed that the young people should be prosecuted. At the same time, the spies - as they called themselves, referring to the observance of the Laws of Moses - gathered in a garden in the city to celebrate Yom Kippur . One of the leaders of the secret Jews of Mallorca, Pere Onofre Cortés alias Moixina , employer of one of the youths and owner of the garden, was arrested along with five other people. From then on, 237 more people were arrested in just one year. With the help of corrupt officials, however, the accused only had to divulge little information and were thus able to divulge only a small number of fellow believers. All of the accused asked to be re-admitted to the church and were pardoned because of that. These trials became known as conspiracies. Part of the penalty consisted of the confiscation of all belongings of the accused. This was estimated at a total of 2 million Mallorcan libras, and it was converted into valid currency on the orders of the Inquisition. It was an exorbitantly high sum of 654 tons of silver, and according to an objection by the Gran i General Consell de Mallorca, there was no such amount on the entire island. In the spring of 1679, five judgments were finally carried out. The first judgment was preceded by the destruction of the garden where the converts met and the sowing of salt. In these judgments, convictions were pronounced against 221 converts in front of an enormous crowd. Afterwards, those found guilty were moved to new prisons that the Inquisition had built with the confiscated property.

La Cremadissa (burning)

After serving their sentence, the majority of those who wanted to pursue the Jewish faith decided to flee the island in small groups. Their clandestine practice was convicted, they were concerned about Inquisition surveillance and harassed by a society that held them responsible for the economic crisis caused by the confiscations. A few managed to escape. In the midst of this process, an anecdotal circumstance accelerated another wave of the Inquisition. Rafel Cortés, alias cap loco , married a woman with a surname typical of converts: Miró. However, she was a Catholic. His relatives did not congratulate him on his marriage, but rather accused him of mixing with bad blood. Despite this, he again denounced some of his co-religionists at the Inquisition and accused them of continuing to practice the forbidden faith. Since they suspected that it was a general complaint, they agreed on a mass escape. On March 7, 1688, a large group of converts wanted to clandestinely set off in an English ship for Amsterdam. But an unexpected storm prevented them from casting off and at dawn they returned to their homes. The Inquisition had become aware of their action and everyone was arrested.

The trials dragged on for three years. The accused were kept strictly separated in order to prevent any collusion, which, together with the religious defeat because it was impossible to escape, weakened the group's cohesion. In 1691 the Inquisition sentenced 88 people in four trials; of 5 the pictures were symbolically burned, of 3 people the bones and 37 were actually killed. Of the latter, 3 people (Rafel Valls and the siblings Rafel Benet and Caterina Tarongí) were burned alive. 30,000 spectators were present.

The announced convictions by the Inquisition included other punishments that would affect at least two subsequent generations: immediate family members, both children and grandchildren, could not hold public posts, become priests, wear jewelry or ride horses. The last two penalties appear to have not been implemented. The other punishments remained in effect beyond the two generations actually sentenced out of sheer habit.

The last trials

The trial chapter was still not closed when the Inquisition opened some proceedings against people denounced by defendants in the 1691 files - although it later dropped them. The majority were already deceased; A single trial was held in 1695 against 11 dead and one living woman who was pardoned. In the 18th century, too, there were two individual trials: in 1718, Rafel Pinya spontaneously reported himself and was pardoned, and in 1720 Gabriel Cortés, alias Morrofés , was briefly in Alexandria and formally converted to Judaism, the last to be sentenced to death by the Mallorcan Inquisition.

There is no doubt that the last few cases are anecdotal. With the trials of 1691, religious decline and ubiquitous fear made it impossible for ancient beliefs to be any support. This fulfilled the goals of the Inquisition: confiscation of property, especially in the trials of 1678; Punishment of heretics, which continued into the 20th century, and the subjugation of converts. From this point on, one can speak of Xuetas in the modern sense.

Anti-Jewish propaganda

La Fe Triunfante

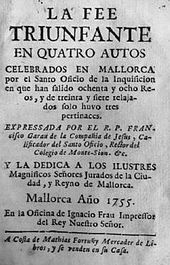

In the course of the convictions of 1691, Francesc Garau, a Jesuit , theologian and active participant in the inquisition trials , published the text La Fe Triunfante en quatro autos celebrados en Mallorca por el Santo Oficio de la Inquisición en qué an salido ochenta i ocho reos, i de treinta, i siete relaiados solo uvo tres pertinaces . Aside from its current importance as documentation and historical source, the main intention of the book was to perpetuate the memory and shame of the converts. It made a considerable contribution to laying an ideological basis for the segregation of the Xuetas and also to maintain it. The volume was reprinted in 1755 and used to argue for a restriction of the civil rights of the Xuetas. It also served as the basis for the 1857 pamphlet La Sinagoga Balear o historia de los judíos mallorquines . In the 20th century, a few new editions were published, but now with the aim of achieving exactly the opposite of the author's intention at the time.

Penitential shirts

Gramalleta or sanbenito was a custom used to punish the defendants of the Inquisition. They were forced to wear penitent shirts. The appearance of the penitential shirts revealed the crimes committed and the expected punishment. After the verdict, a picture was painted with the defendant in his penitent shirt and his name. In the case of Mallorca, these images were exhibited in public in the Santo Domingo convent to immortalize the memory of the convictions.

Due to the deterioration of the situation from the perspective of the Inquisition since the 17th century, it ordered a reform several times. But the situation was not exactly easy because of the huge number of surnames, some of which matched surnames from the nobility. In 1755 the reform was finally implemented. However, only a reform of the ordinances was implemented from 1645 onwards, and thus only the surnames of clearly proven Jews were taken into account. The surnames of around 1,000 convicts and 200 accused of secret Judaism fell under the table. By reducing the surname list, it became even easier for the majority of the Mallorcan population to engage in the discriminatory ideology, because the group of the accused converts was now precisely - and incorrectly - defined and finally marginalized.

In the same year, 1755, in which La Fe Triunfante was reissued, Relación de los sanbenitos que se han puesto, y renovado este año de 1755, en el Claustro del Real Convento de Santo Domingo, de esta Ciudad de Palma, por el Santo Oficio de la Inquisición del Reyno de Mallorca, de reos relaxados, y reconciliados publicamente por el mismo tribunal desde el año de 1645 , in order to insist, despite the active opposition of those concerned, not to forget what happened . The penitential shirts were on public display until 1820 when a group stormed Santo Domingo and burned it down.

The Community

The activities of the Inquisition, which initially wanted to force the disappearance of the Jews by forcing them into the Christian community, provoked an almost unique paradoxical effect . They kept the memory of the punished, and of all the namesake of the dishonored families, even if they were not related or even sincere Christians. As a result, a society developed that, although there were no longer any Jewish elements, had a group-like structure that resembled that in the rest of the Jewish communities of the Diaspora : its role in the economic system, the strong cohesion of the group, internal endogamy, cooperation - and the model of interdependence, the Jewish consciousness and the social hostility towards the outside are elements which, to varying degrees, continue to identify them as Jews, or rather as Catholic Jews. They provided the organizational basis of the group after the shock of the Inquisition. In the Mallorcan context of the 17th and 18th centuries, the communal solution corresponded to a much tighter social structure than in previous centuries, in which aristocrats, merchants, craftsmen, day laborers and farmers also formed dense, endogamous units among themselves, which up until before lasted a comparatively short time, even if they were not socially stigmatized.

But the society that emerged after the trials of the Inquisition, where the changes in religious orientation were added, modified just as essential aspects of the previous structure. And once the economic importance that they had previously possessed was regained, a fierce and ongoing process of active struggle for equality began that marked their history. In this environment, individual personalities emerged at different times who stood out for their struggle for equality: es sastre xueta Rafel Cortès Fuster, the merchant Miquel Forteza i Pinya and Gabriel Cortès Cortès. On the other hand, society at that time, especially civil and religious institutions, armed itself, starting from La fe triunfante, with a textbook against equality that developed into the 18th century and lasted into the 20th century.

The 18th century

The War of Succession (1706-1715)

As with the rest of the island's population, the Xuetas had both Habsburg and Bourbon supporters. On the one hand, the French ruling house was perceived as an element of religious and social modernization because it was hoped for something completely different from the previously experienced oppression and discrimination by Austrian rule, especially under the last Carlos. A small core of Xuetas, led by Gaspar Pinya, an importer and merchant of clothing who supplied nobles, were active supporters of Philip V. In 1711, a conspiracy they sponsored was exposed, jailed, and their property confiscated. Nonetheless, after the conflict ended, they were given the privilege of wearing a sword and public honorary positions as compensation, and the rest of their community suffered no harm.

The religious conflicts

Until the trials of the Inquisition, the existence of monks and nuns del Segell was quite common, some of them were even related to Jews, but after the execution of sentences it became much more difficult to obtain religious offices, for which an episcopal permission was required. The simplest solution was to join a monastery abroad that did not require permission, which meant they had to leave the island, or they joined a smaller order and waited for a more tolerant bishop. Both possibilities brought conflict with them.

Expulsions of Jewish clergymen on royal decree in 1739, 1748 and 1763 are documented. With regard to the priesthood, the head of the cathedral repeatedly forced the bishops to prohibit any permission in their own and other dioceses. In one case, a monk waited 30 years to be ordained a priest.

Conflicts in the guilds

As early as the 17th century, the statutes of the limpieza de sangre were introduced into different areas, although there were indications of a relatively loose handling up to the trials of the Inquisition. From that time on, they established themselves. In 1689 a split took place. The converts were no longer allowed to join the guild cooperatives: dyers (1691), bakers (1695), surgeons and bathers (1699), tailors (1701), esparto sellers (1702), carpenters (1705), clerks and authorized signatories (1705) and painters and sculptor (1706). In 1757 the Seiler split up into two camps. Because of this, the converts were ultimately limited to the guilds of their traditional professions: haberdashery, jewelers, shopkeepers and peddlers. These had no exclusion provisions, but were considered almost exclusive. This led to conflicts, the best-known case being the saga de sastres Cortés : They litigated for 30 years and over three generations until they were allowed to practice their profession. The stay of Rafel Cortés, alias es sastre xueta , in Madrid to defend himself in the legal dispute was the trigger for the next steps, which finally ended in the decrees of Carlos III.

The reissue of La Fe Triunfante in 1755

The quoted Rafel Cortès Fuster, Tomàs Forteza and Jeroni Cortès, alias Geperut , tried in 1755 with protests in a meeting in Mallorca to prevent the re- edition of La Fe Triunfante . The intervention of the Inquisitor finally allowed the sale to resume.

Emissaries (1773–1788)

In 1773 six emissaries were appointed. They were known as perruques because of their pompous furnishings, which they displayed during their business negotiations before King Charles III. wore in order to demand complete social and legal equality compared to all other Mallorcans. Talks with Mallorcan institutions that vehemently opposed the demands of the descendants of the converts were ordered from the court. The incident turned into a long and costly process in which the parties put forward their respective arguments. The documents produced give an idea of the point at which the discrimination came from deep ideological convictions and from defiance of the persistent demand for equal rights.

In October 1782 the Court of Auditors of the Real Audiencia of Mallorca, although it was known that the result of the deliberations would be in favor of the xuetas, requested a petition with clearly racist arguments in which the suspension of the agreement and the expulsion of the Jews from Menorca and Cabrera (island) with severe restrictions of their freedom demanded.

Finally, the king was inclined in favor of the xuetas, and on November 29, 1782 the Real Cédula was signed, which granted freedom of movement and freedom of residence, the demolition of every architectural element that served to separate the Jewish quarter of Segell and the prohibition of verbal abuse and abuse and enacted the use of slanderous expressions. In a somewhat cautious manner, the monarch was willing to allow them free career choice and entry into the navy and the military. However, this decree should only be implemented when the mood has calmed down after a while.

Less than half a year later, the delegates returned with the same demand that they be allowed to practice all professions. They said the allegations and discrimination had not decreased and protested the display of penitent shirts at Santo Domingo Monastery. The king then called a meeting to investigate the situation. The following were proposed: removal of the penitential shirts, prohibition of La Fe Triunfante , distribution of the xuetas throughout the city, elimination of any formal obstacles to mutual aid among the xuetas, access without restrictions to all ecclesiastical offices, universities and the military, abolition of the guilds and deletion of the statutes of the limpieza de sangre and, if this were not possible, a limit of 100 years (the last two provisions should apply to the entire kingdom).

A discussion phase began again, and in October 1785 there was a second Real Cédula , which however hardly came close to the proposals of the convened assembly. Only access to the military and public office was granted. In 1788, a final decree finally stipulated full equality in the exercise of the profession. However, this made no reference to access to universities or church offices. In the same year efforts were made by the court and the main authority of the Inquisition to remove the penitential shirts from the monastery, but without success.

Probably the most noticeable effect of the Reales Cédulas was the slow breakdown of the calle . In some localities, small groups got together and slowly and carefully established themselves in other streets and communities. Social discrimination, maternal endogamy, and the exercise of traditional services did not change, but most importantly, the divisions continued to apply in the areas of honorary degrees, upbringing, and religion. This area did not affect the legal regulation.

19th century

End of the old rule (1808–1868)

Mallorca was not occupied during the Napoleonic invasion and, in contrast to Cádiz , primarily refugees with the most indomitable ideology and inclination to the old rule established themselves; Against this background, the xuetas of 300 soldiers mobilized for the front were accused of being guilty of the invasion situation and were attacked by them in their Segell district . In 1812, the Constitución de Cádiz , which was valid until 1814, abolished the Inquisition and introduced the full and longingly awaited equality. Whereupon the most active xuetas joined the liberal movement. In 1820, when the constitution was reinstated, a group of xuetas raided the headquarters of the Inquisition and the Santo Domingo convent and burned the documents and penitential shirts. When this was again abolished, the quarter was again attacked and looted in 1823. Such episodes are often encountered in this epoch, even in smaller towns such as Felanitx, Llucmajor, Pollença, Sóller, Campos etc. In the religious context, an event of 1810 became significant: the priest Josep Aguiló, alias capellà Mosca , made it after countless attempts to preach in the Church of San Felipe Neri; this ended a few days later with a storm on the church and the pulpit in the campfire.

Progress coincided with the establishment of recreational and mutual aid institutions, and they joined liberal parties. The first was Onofre Cortés in 1836, who was appointed councilor in Palma City Hall. For the first time since the 16th century a xueta held a post of equal rank. From then on, his presence in the city council and in the meetinghouse was normal. Between 1850 and 1854 a long criminal case for insults developed, known as Pleito de Cartagena , because two young people xuetas in the Casino Balear had been excluded from the carnival celebrations because of their origins. It ended with a sentence for the chairman of the association. In 1857, La sinagoga balear o historia de los judíos de Mallorca was published. Juan de la Puerta Vizcaíno signed the document, most of which reproduced La Fe triunfante and a year later by Tomàs Bertran i Soler with Un milagro y una mentira. Vindicaciäon de los mallorquines cristianos de estirpe hebrea was answered.

End of the century (1869–1900)

Although the ideological division within this society extended to before the trials of the Inquisition, it was revealed during this virulent change: A certainly small but influential group, avowedly liberal (later republican) and moderately hostile to the Church, militantly advocated the abolition of all forms of discrimination; and another, perhaps majority group, but hardly noticeable, was ideologically conservative, deeply religious, and went unnoticed. Basically, both strategies intended the same thing: the disappearance of the xueta problem, one by proving injustice and the other by imitating the rest of society.

Whenever possible, some better-off families gave their children a high level of education. They then played an important role in the aristocratic movements of that era. In particular, the primary role they played in the Renaixença catalana , in their commitment to the language and in the reintroduction of the Juegos Florales , must be mentioned. The first noticeable personality to be mentioned is Tomàs Aguiló i Cortès at the beginning of the 19th century and among the notable successors were: Tomàs Aguiló i Forteza, Marian Aguiló i Fuster, Tomàs Forteza i Cortès, Ramón Picó i Campamar, etc. Josep Tarongí Cortès , a priest and writer who completed his studies under particularly difficult conditions and had to achieve his canonical due to his origin outside of Mallorca, is also worth mentioning. He played a leading role in one of the biggest waves of polemics on the Xueta issue in the 19th century because he was forbidden to preach in the church of Sant Miquel in 1876. That is why he, together with another clergyman, Miquel Maura, Antonio Maura's brother, started a debate in which many other writers took part and which was followed with interest both inside and outside Mallorca.

20th century

Until the Second World War (1900–1945)

Major changes took place in Mallorca during the first third of the 20th century. The social indolence of the previous centuries began to disappear: the city of Palma began to expand beyond its city walls, attracting new residents (Spaniards and foreigners) for whom the xueta issue was completely irrelevant. The economy also opened up to less traditional models and the professional ties to an origin were loosened. In this environment, the town planner and politician Guillem Forteza Pinya was mayor of Palma as xueta from January to October 1923. From 1923 to 1930, during the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera, Joan Aguiló Valentí, alias Cera , and Rafel Ignasi Cortès Aguiló, alias Bet , held the mayor's office. The short period of the Second Republic also played an important role because of the official secularism and because a large part of the xuetas sympathized with the new state model as well as with the then liberal ideas. As an event of great symbolic power, a Xueta priest preached the sermon in the Mallorcan cathedral for the first time during the Republican Republic.

At the end of the republican period , many xuetas fell victim to Franco's oppression . But some also supported the military rebellion. Because a collaboration with the European Jews was assumed, at the beginning of the civil war and later in the 1940s, at the request of the Falange movement and the German Nazi government, lists and questionnaires were prepared for a possible control of the Xueta numbers and their possible deportation became planned in concentration camp. In order to avoid any activity in this direction, a report was recommended to Bishop Miralles which increased the number of those affected to an unimaginable number.

From post-war Europe to today (since 1945)

The prejudice against the xuetas began to disappear irrevocably from the 1950s due to the flourishing tourism industry. This brought about great demographic changes and urban growth, which definitely changed the traditional social structure and model of group relocation. In this way, the structured community became a social category that was well aware of its origin. This is confirmed in innumerable aspects, the most important of which is certainly the gradual disappearance of endogamous marriages; in Palma the numbers fell from 85% in 1900 to 20% in 1965 and now they are practically non-existent.

But still in 1966 provoked the publication of Els descendents dels jueus conversos de Mallorca. Quatre paraules de la veritat by Miquel Forteza i Pinya, the brother of Mayor Guillem, the last major public polemic on the Xueta question. It was in this publication that Baruch Braunstein's successes in the Archivo Histórico Nacional de Madrid , published in the United States in 1936, became known. These showed that more than 200 Jewish surnames were punished on Mallorca. At that moment, the withdrawal of discrimination can symbolically be dated solely to the non-public area, because it practically eliminated accusations in public. The publication of Forteza was also the beginning of a successful series of publishers on the island, which is currently being continued and made the Xueta question one of the most studied topics in Mallorcan historiography.

The religious freedom created by the laws at the end of Franco's government enabled certain contact with Judaism and encouraged attempts at rapprochement in the 1960s, which did not materialize except in the case of Nicolau Aguiló, who emigrated to Israel in 1977, and who returned to Judaism became a rabbi under the name Nissan ben Avraham . In any case, Judaism and the xuetas had a certain ambivalent relationship to one another, because the xuetas are Jews with a Christian tradition. This was ignored by the political and religious institutions in Israel. All that mattered to them was the fact that they had a Christian tradition. Whereas for the xuetas who were interested in some form of rapprochement, the criterion for distinguishing them from others was always that they were Jews. Perhaps this duality explains the Judeo-Christian syncretic cult, called cristanismo xueta , preached by Cayetano Martí Valls. An important event with the beginning of the democratic government was the election of Ramón Aguiló as socialist mayor of Palma until 1991. His election by the citizens can be seen as the main evidence of the end of discrimination. Ultimate confirmation would be the case of Francesc Aguiló i Pons, who was mayor of the regional left of Campanet from 1987 to 2007 .

None of this automatically implies the complete disappearance of discrimination. In a survey conducted in 2001 by the Universidad de las Islas Baleares , 30% of all respondents said that they would never marry a xueta and 5% would not make friends with xuetas either. While these numbers are quite high, one has to take into account in evaluating them that most of the proponents of discrimination belong to the older generation.

In recent years, the association ARCA-Llegat Jueu , a research group on Memoria del Carrer , the Instituto Rafel Valls with a religious character, the Segell magazine , and the City of Palma has joined the Red de Juderías network . All this suggests that previously secret activities are now lived out with an open naturalness.

Literary work

Since the beginning of the 19th century the xuetas were fairly present in literary creation in the Balearic Islands . But the topic of xueta can also be found in literature beyond the Balearic Islands. It was probably most processed in poetry, and there in a bitter tone. However, there is no systematic collection of the literature that has survived to this day, although the bibliography contains some special individual works. There is also much published literature in which the topic xueta plays an important role and which is of high literary value, such as Mort de dama or Dins el darrer blau .

Literary works

Works on Mallorcan Judaism are also listed:

poetry

- Autos de fe celebrats per la Inquisició de Mallorca en els darrers anys del segle XVII , Oliver Gasà, Bartomeu , around 1691.

- L'adeu del Jueu , Picó i Campamar, Ramon , 1867.

- La filla de l'argenter , Picó i Campamar, Ramon , 1872.

- A SM el Rey , Tarongí Cortès, Josep , 1877.

- The Chueta , Levin, D. , 1884

- Lo fogó dels juheus , Pons i Gallarza, Josep Lluís , 1892.

- El xueta , d'Efak, Guillem , 196 ?.

- Càbales del Call , Fiol, Bartomeu , 2005.

Novels and short stories

- Jorge Aguiló o Misterios de Palma , Infante, Eduardo , 1866.

- Los muertos mandan , Blasco Ibáñez, Vicente , 1909.

- La mayorquine , Gaubert, Ernest , 1914.

- Por el amor al dolor. Una chuetada , Monasterio, Antonia de , 1924.

- Mort de dama , Villalonga PonsS, Llorenç , 1931.

- La custodia Aguiló Aguiló, Marià , 1956.

- Els emparedats , Moyà i Gilabert de la Portella, Llorenç , 1958.

- Primera memoria , Matute, Ana Maria , 1960.

- El chueta , Ferrà i Martorell, Miquel , 1984.

- Contes del Call , Ferrà i Martorell, Miquel , 1984.

- Carrer de l'Argenteria, 36 , Serra i BauçàA, Antoni , 1988.

- La por , ben Avraham, Nissan , 1992.

- Dins el darrer blau , Riera, Carme , 1994.

- La casa del pare , Segura Aguiló, Miquel , 1995.

- L'atlas furtiu , Bosch, Alfred , 1998.

- Cap al cel obert , Riera, Carmé , 2000.

- Josep J. Xueta , Pomar, Jaume , 2001.

- El darrer chueta de Mallorca , Aguiló, Tano , 2002.

- Le maître des boussoles , Rey, Pascale , 2004.

- La aguja de luz , Turrent, Isabel , 2006.

- Els crepuscles més pàl • lids , López Crespí, Miquel , 2009.

theatre

- Entremès d'un fadrí gran pissaverde , anonymous, 18th century

- La cua del chueta , Ubach i Vinyeta, Francesc d'Assis , 1881.

- Dilluns de festa major , Mayol Moragues, Martí , 1955.

- El fogó dels jueus , Moyà i Gilabert de la Portella, Llorenç , 1962.

- Els comparses , Cortès CortèsS, Gabriel , 1963.

- A l'ombra de la Seu , Villalonga Pons, Llorenç , 1966.

Travel records and memoirs

- Voyage dans les lles Baleares et Pithiuses , Grasset de Saint-Sauveur, André , 1800–05.

- Notas y observaciones hechas en mi viaje y permanencia en Mallorca , de Cabanyes i Ballester, Jose Antonio , 1837.

- Un hiver a Majorque , Sand, George , 1839.

- Viaje a la isla de Mallorca en el estio de 1845 , Cortada, Juan , 1845.

- L'illa de la calma , Rusiñol, Santiago , 1919.

- Del meu temps , Forteza i Pinya, Miquel , 1926-1962.

- Babels i Babilònics , Fuster i Ortells, Joan .

- Diari 1957-1958 , Fuster i Ortells, Joan

- A dead branch on the tree of Israel , Graves, Robert , 1957.

- Memòria chueta , Segura Aguiló, Miquel . 1994.

- La nissaga d'un chueta , Cortès, Llorenç . 1995.

- Històries del Carrer , Forteza, Conxa . 2006.

- Raíces chuetas, alas judías . Segura Aguiló, Miquel . 2007.

bibliography

- Anonymous: La Inquisición de Mallorca. Reconciliados y Relajados, 1488-1691 . Ed .: Perdigó. Barcelona 1946.

- Anonymous; Muntaner, Lleonard (introduction): Relación de los Sanbenitos: 1755 . Miquel Font, editor, Palma de Mallorca 1993, ISBN 978-84-7967-018-4 .

- Anonymous; Pérez, Lorenzo (editing, introduction and commentary): Anales judaicos de Mallorca . Luís Ripoll, editor, Palma de Mallorca 1974, ISBN 84-400-7581-2 .

- ben-Avraham, Nissan: Els anussim. El problema dels xuetons segons la legislació rabínica . Miquel Font, editor, Palma de Mallorca 1992, ISBN 84-7967-009-6 .

- Bibiloni Amengual, Andreu: El comerç exterior de Mallorca. Homes mercats i productes d'intercanvi (1650-1720) . El Tall, Palma de Mallorca 1995, ISBN 84-87685-49-8 .

- Braustein, Bàruc; Massot i Muntaner, Josep (prologue): Els xuetes de Mallorca . Curial, Barcelona 1976, ISBN 84-7256-078-3 (Original title: The chuetas of Mallorca. Conversos and the Inquisition of Mallorca. ).

- Colom Palmer, Mateu: La Inquisició a Mallorca (1488–1578) . Curial, Barcelona 1992, ISBN 84-7256-993-4 .

- Cortès Cortès, Gabriel; Serra, Antoni (preliminary study): Historia de los judios mallorquines y de sus descendientes cristianos . Miquel Font, editor, Palma de Mallorca 1985, ISBN 84-86366-05-4 .

- Cortès Cortès, Gabriel; Piña Homs, Roman: Les cartes romanes de Mossen Pinya . UIB, Palma de Mallorca 2000, ISBN 84-7632-588-6 .

- Cortès, Llorenç: La nissaga d'un xueta . Lleonard Muntaner, Palma de Mallorca 1995, ISBN 84-88946-14-7 .

- Rubén Darío : Mallorca's gold. Stories. Translated from the Spanish by Ulrich Kunzmann. Reclam's Universal Library , 1018. Leipzig 1983

- Font Poquet, Miquel S .: La fe vençuda. Jueus, conversos i xuetes a Mallorca . Miquel Font, editor, Palma de Mallorca 2007, ISBN 978-84-7967-119-8 .

- Miguel Forteza: Els descendents dels jueus conversos de Mallorca. Quatre mots de la veritat . Editorial Moll, Palma de Mallorca 1970, OCLC 654155154 .

- Francisco Garau, Llorenç Pérez (prologue), Lleonard Muntaner (preliminary version): La fe triunfante . Imagen / 70, Palma de Mallorca 1984, ISBN 84-86366-00-3 .

- Juan and Eva Laub, Carmelo Lisón Tolosana (prologue): El mito triunfante: estudio antropológico-social de los chuetas mallorquines . Miquel Font, editor, Palma de Mallorca 1987, ISBN 84-86366-28-3 .

- Moore, Kenneth: Los de la calle. Un estudio sobre los chuetas . Siglo XXI de España editores, SA, Madrid 1987, ISBN 84-323-0602-9 (Original title: Those of the street: the Catholic-Jews of Mallorca .).

- Pérez Martínez, Lorenzo (edition); Riera i Monserrat, Francesc (introduction): Reivindicación de los judíos Mallorquines . Fontes Rerum Balearium, Palma de Mallorca 1983, ISBN 84-398-0247-1 .

- Picazo Muntaner, Antoni: Els xuetes de Mallorca: grups de poder i critojudaisme al segle XVII. Sobre jueus i conversos de les Balears . El Tall, Palma de Mallorca 2006, ISBN 84-96019-34-9 .

- Piña Homs, novel: El plet de Cartagena (1850–1855): Discriminacions de sang i dues burgesies en lluita a la Mallorca del XIX . Miquel Font, editor, Palma de Mallorca 2006, ISBN 84-7967-113-0 .

- Planas Ferrer, Rosa; Pons, Damià (prologue): Els malnoms dels xuetes de Mallorca . Lleonard Muntaner, Palma de Mallorca 2003, ISBN 84-95360-83-7 .

- Pons Pons, Jerònia: Companyies i mercat assegurador a Mallorca (1650–1715) . El Tall, Palma de Mallorca 1996, ISBN 84-87685-51-X .

- Porcel, Baltasar: Los chuetas mallorquines. Quince siglos de racismo . Península, Barcelona 2002, ISBN 978-84-297-5059-1 .

- Porqueres i Gené, Enric: L'endogàmia dels xuetes de Mallorca. Identitat i matrimoni en una comunitat de conversos (1435–1750) . Lleonard Muntaner, Palma de Mallorca 2001, ISBN 84-95360-18-7 (Original title: Lourde alliance. Mariage et identité chez les descendants de juifs convertis à Majorque (1435–1750) . Translated by Riera i Montserrat, Francesc).

- Porqueres i Gené, Enric; Riera i Montserrat, Francesc: Xuetes, nobles i capellans (segles XVII-XVIII) . Lleonard Muntaner, Palma de Mallorca 2004, ISBN 84-96242-12-9 .

- Quadrado, José Maria: La judería en Mallorca en 1391 . Lleonard Muntaner, Palma de Mallorca 2008, ISBN 978-84-92562-08-4 .

- Riera i Montserrat, Francesc; Melià i Pericàs, Josep (introduction): Les lluites antixuetes del segle XVIII . Edición Moll, Palma de Mallorca 1973, ISBN 84-273-0341-6 .

- Riera i Montserrat, Francesc: Xuetes i antixuetes. Quatre històries desedificants . El Tall, Palma de Mallorca 1993, ISBN 84-87685-32-3 .

- Riera i Montserrat, Francesc; Porqueres i Gené, Enric (prologue): La causa xueta a la cort de Carles III . Lleonard Muntaner, Palma de Mallorca 1996, ISBN 84-88946-24-4 .

- Riera i Montserrat, Francesc: Els xuetes des de la intolerancia a la llibertat . Lleonard Muntaner, Palma de Mallorca 2003, ISBN 84-95360-93-4 .

- Sand, George: Un invierno en Mallorca . Edicions Cort, Palma de Mallorca 2004, ISBN 978-84-7535-417-0 .

- Angela Selke: Los chuetas y la Inquisición. Vida y muerte en el ghetto de Mallorca (= Ensayistas . No. 80 ). Taurus ediciones SA, Madrid 1972, OCLC 403904 (Original title: The Conversos of Majorca: Life and Death in a Crypto-Jewish Community in XVII Century. ).

- Tarongí Cortès, José: Algo sobre el estado religioso y social de la isla de Mallorca . Miquel Font, editor, Palma de Mallorca 1984, ISBN 84-86366-04-6 .

- Sail. Revista de Historia y cultura jueva . No. 1, 2, 3, 2005-2006 . Lleonard Muntaner, ISSN 1696-6503 , OCLC 70912578 .

See also

Web links

- Research group Memòria del Carrer

- Association for historical processing ARCA-Llegat Jueu

- Segell magazine ( Memento from June 20, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- Association of Jewish Culture Tarbut Sepharat. Mallorca

- Red de Juderías (Association of the Jewish Quarter of Spain)

Remarks

- ↑ Estimate based on data from the Instituto Nacional de Estadística de España in the Balearic Islands.

- ↑ ... You are of the sex of those from the Strait of the Sail, who are commonly called Xuetas ... , L'endogàmia ... p. 42, Braunstein, Els xuetes ... p. 13.

- ↑ Juetó is documented in 1580. P. de Muntaner, Martí: Una familia del brazo noble mallorquín durante el siglo XVII. P. 636, paragraph 7, Homenaje a Guillem Rosselló Bordoy, II, Palma 2002. Moore derives the term from a presumably old Mallorcan word, xuhita , which in turn is not documented, Moore, Los de la calle ... p. 23.

- ↑ 1595 it appears as an insult, next to juheu (jude), but also in a completely different context. Porqueres, L'endogàmia…. P. 27. In the 19th century, pilgrims shouted at young people Xuia, xuia marrana , Pérez, Anales…. Pp. 97 and 111.

- ↑ Some of the older authors motivated not to eat pork, Garau, La fe… Pérez, Anales…. P. 62, Font, La fe vençuda… p. 118, while others showed themselves eating meat to prove that they have nothing against the Jewish faith, Braunstein, Los xuetas… p. 13.

- ↑ Braunstein describes the hypothesis that chucho , derived from the French chouette , colloquially dog, comes from Castilian, as careless, Braunstein, Els xuetes ... p. 13.

- ↑ Diccionari Català-Valencià-Balear , Alcover-Moll, Xuetó .

- ↑ Del carrer del Segell is the oldest known name of the group and was documented in 1617. P. de Muntaner and Enric Porqueres Subendogamias en el Mediterráneo: Los ejemplos mallorquines de la aristocracia y de los descendientes de los judíos p. 93 a Memorias de la Academia Mallorquina de Estudios Genealógicos , Palma 1994.

- ↑ Del Carrer documented in 1658, Porqueres, L'endogàmia…. P. 79.

- ↑ The Argenteria or platería became an important city building with the urban reform of the street calle Colón in the middle of the 19th century, which practically brought about the physical disappearance of the street “calle del Segell”, Pérez, Anales… pp. 104-105.

- ↑ Forteza, Els descendents… pp. 24–28.

- ↑ It is forbidden to insult these individuals or to cause them suffering, to address them with a hateful voice and disdain, and to call them neither Jews, Hebrews, nor Xuetas ... (from the decrees of Carlos III), Forteza, Els descendents ... p. 47.

- ↑ Diccionari Català-Valencià-Balear , Alcover-Moll Jodio or Judio .

- ↑ Perez, Anales…. P. 75.

- ^ Moore, Los de la Calle ... p. 31.

- ↑ Occasionally the words xueta and judío were used contemptuously in the cultural Spanish environment to refer generally to the Mallorcan and Balearic population , or in an analogous way to the fenicios to refer to individual people who did not come from the Balearic Islands, Antonio Maura and Juan March, for example, were referred to several times as such; Moore, p. 5, Los judíos y la segunda repúblca. 1931–1939 Isidro González García, Madrid: Alianza, 2004, p. 63, El último Pirata del mediterráneo, Manuel Domínguez Benavides, Tipografía Cosmos, Barcelona, 1934.

- ↑ Forteza, Els descendents ... , in detail.

- ↑ This is the exemplary list by Miquel Forteza, Els descendents…, p. 18 but the subject is complex, in earlier lists Valleriola (almost obliterated) or Valentí (originally the house name for the Fortesa family) sometimes do not appear; Enrich is also not on any list (originally house name for the Cortès family); In the lists of the last prisoners during the Inquisition, the surnames Galiana, Moià and Sureda appear, which were actually not considered to be typically Jewish names; on the other hand, Picó and Segura are not found among the convicts in the 17th century, although they are Jewish surnames.

- ↑ Quadrado. La judería… , in detail.

- ↑ Anónimo, Reconciliados y Relajados…, in detail.

- ↑ Forteza, Els descendents ... p. 14.

- ↑ In this context one can come across secret ancestors of converted Mallorcans (according to purely family-internal tradition) who were proud of their ancestry, but hostile to the xuetas, Moore, Los de la calle ... pp. 187 and 192.

- ↑ Tres poblacions genèticament diferenciades a les Illes Balears. (PDF; 333 kB) Accessed July 23, 2013 (Catalan).

- ↑ Bases genètiques de la febre mediterrània familiar a la població espanyola, dinàmica genòmica i història natural de les mutacions en el locus MEFV. (PDF) (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on July 21, 2011 ; Retrieved January 31, 2010 (Catalan). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Els investigadors del Laboratori de Genètica de la UIB i de l'Hospital Universitari Son Dureta confirmen la prevalença d'una mutació en la població xueta relacionada amb l'hemocromatosi, un trastorn metabòlic del ferro. March 3, 2006, archived from the original on June 15, 2013 ; Retrieved July 23, 2013 (Catalan).

- ↑ Cortès, Historia… , Volume I, in detail; Font, La fe vençuda… pp. 25–39.

- ↑ On the other hand, there were strict rules for slaves very early on, although their ancestors were Christians, Greeks and Moors, Riera, Lluites…. P. 37.

- ↑ L'origen dels conversos mallorquins. Pp. 43–46 in Colom La Inquisició… .

- ↑ Moore, Los de la Calle… pp. 112–116.

- ↑ This exile must not be confused with the expulsion of the Jews in 1492. This had no effect on Mallorca, since according to official information there have been no Jews there since 1435.

- ^ The text by Braunstein from 1936 is the first to reproduce lists of Mallorcan prisoners from the 15th and 16th centuries. But it contains a relatively large number of transcription errors which were subsequently corrected in 1946 in reconciled and mitigated cases. The piece of text is difficult to obtain, but it exists with the title Judíos y descendientes de judíos conversos de Mallorca as a special edition of the Historia de Mallorca by Mascaró Passarius, 1974.

- ↑ Even so: While the statues of blood purity (limpieza de sangre) were ubiquitous in Castile in the 16th century, they are almost unknown in Mallorca. Porqueres, L'endogamia ... p. 25.

- ↑ Porqueres, L'endogàmia… in detail, on religious unity, pp. 91–106, on the practices of disguising oneself as a Jew: Braunstein, Els xuetes… pp. 165–188, Picazo, Els xuetes… p. 13– 56.

- ↑ Colom, La Inquisició… pp. 186–189.

- ↑ Fontamar's report is a copy in an Inquisition file from 1674. That is why Braunstein in Els xuetes… p. 279–286 accepted the date. In the history of writing this was also mentioned more often. Fontamar was the driving force behind the pen and the Inquisitions tax clerk on Mallorca from 1632 to 1649, Gran Enciclopedia de Mallorca, Vol. 5, p. 366. Porqueres assumes that Mateu Colom and Lleonard Muntaner showed the elaboration in 1632; Porqueres, L'endogamia ..., p. 40, note 38.

- ↑ Bibiloni, El comerç… and Pons Companyies… .

- ↑ Hebrew Community of Livorno ( Memento from June 29, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Cortès, La nissaga ... p. 153.

- ↑ Porqueres, L'endogàmia… , in detail.

- ↑ Braunstein, Els xuetes ... pp. 114 and 115.

- ↑ Braunstein Els xuetes… pp. 116–120.

- ↑ Braunstein Els xuetes ... S. 115 and 116th

- ↑ Riera, Lluites ... p. 17.

- ↑ Braunstein, Els xuetes… pp. 121-139.

- ↑ Braunstein, Els xuetes… pp. 140–142.

- ↑ Specifically presented in Selke, Los Xuetas y la Inquisición ... , in detail.

- ↑ Braunstein, Els xuetes ... pp. 147 and 148.

- ↑ Braunstein, Els xuetes… pp. 162–164 and 190–198.

- ^ Moore, Los de la calle ... p. 137, 199.

- ↑ Francesc Guerau ( Memento from June 29, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ La Fe Triunfante , 1984, especially the study by Lleonard Muntaner.

- ↑ Some excerpts were shocking because of their brutality and lack of sensitivity. The third act of faith in 1691 came true five days later […]. They were the siblings Catalina and Rafel Benet Tarongí and Rafel Valls. The father created his most repulsive and at the same time most sensual side by describing the burn: […] While the smoke reached Valls, he remained motionless, but when the shouts reached him, he defended himself as best he could, he struggled until it got there was no longer possible for him. He was fat as a pig and suddenly he was burning from the inside and although the calls did not reach him, his flesh burned like ashes. It burst in the middle and its entrails fell out like Judas' [...] ; Porcel, Los xuetas mallorquines ... p. 56.

- ↑ Reconciliados y relajados. Pp. 17-21.

- ↑ Relación de los Sanbenitos , especially the introduction by Lleonard Muntaner.

- ↑ Strictly speaking, and from the point of view of formal Judaism , Jews and Catholics represent incompatible concepts; in this context it must be understood more in a syncretistic sense, with a common ethical origin and also common anthropological and cultural aspects and not from a religious point of view; Moore, los de la calle ... pp. 9, 22, 137, 199.

- ^ Moore, Los de la Calle ... p. 147.

- ^ Moore, Los de la Calle ... p. 151.

- ↑ This view, generalized by historiography, is contradictory because of the strict introduction of the estatutos de limpieza de sangre during the first term of office of Philip V (1700–1706). These precisely determined the punishment of the viceroy. However, it was not confirmed by his policy in the post-war period (1715-1740).

- ↑ Riera, Lluites ... , 1973, pp. 29-35.

- ↑ Porqueres, Riera, Xuetes, nobles y capellans… pp. 190–224.

- ↑ This practice was used until the mid-20th century, especially among women; Forteza, Els descendents ... p. 73.

- ↑ Riera, Lluites… pp. 82–86.

- ↑ The Jewish ordination did not normalize until Bishop Bernat Nadal i Crespí , at the end of the 18th century, in 1848 they were tolerated in the seminary as external students, in 1866 entry became compulsory in order to continue their studies, but the boarding school they were not allowed. That's why they had to leave the island to study. These restrictions did not change until the end of the 19th century; Riera, Lluites… , Piña, Las cartas romanes… Cortès, Història… volumes. II, pp. 364-367.

- ↑ Porqueres, La endogamia ..., pp. 25-27.

- ↑ In addition, the converted were excluded; Gerber (1431); Blacksmith's shop (1543); Pharmacist, sugar and spice dealer (1553); Sieve maker and surveyor (1571); Wax puller; Potter; Hatter; Silkworms; Furrier; Linen cutters and shoemakers (measures will have been taken against the majority who do not have a date after the trials), Riera, Lluites…. Pp. 41-54.

- ↑ Riera, Lluites…. Pp. 55-78.

- ↑ Font, La Fe vençuda. Pp. 87-89.

- ↑ For the entire paragraph Riera, La causa xueta… , in detail, Quatre històries… pp. 21–55 and Pérez, Riera, Reivindicación… in detail

- ↑ Pérez, Riera, Reivindicación… pp. 269–278.

- ↑ This exclusion was negotiated, Campomanes refers in a petition to the king to the reservation of the ordinances: avoid “any designation which could have offended the nobility of the kingdom” (it refers to the attainment of honor); “And also not pleasant to speak of literary grades, because there are too many students on Mallorca, and because it is important to increase the number of traders, artisans and workers ... the opposite would turn out ... they would idle people and imitators to be of the nobility; and that the same silence deserves respect to empower them ... to exercise religious services, the degradation of which is clearly visible in Mallorca ”; Riera, La causa xueta ... p. 98.

- ↑ Font, La fe ... vençuda pages 96 and 97th

- ↑ Font, La fe ... vençuda S. 98-112.

- ↑ Gran Enciclopedia de Mallorca Volume 18, p. 258.

- ↑ Pérez, Anales ... p. 157, Cortès, Història ... Vol. II, p. 363.

- ↑ Josep M. Pomar Reynés, La Paz, el casino de l '"altra" burguesia de Palma , Segell No. 3, pp. 100-102; Moore, Los de la calle ... p. 32.

- ↑ Cortès, Història ... Vol. II, p. 363.

- ↑ Pinya, El Plet ...

- ^ Moore, Los de la Calle ... pp. 154–155.

- ↑ Font, La fe ... vençuda S. 138th

- ↑ Tarongí, Algo ... in detail; Riera, Los xuetas ... pp. 121-138.

- ^ Moore, Los de la Calle ... p. 158.

- ↑ Font, La fe ... vençuda S. 150 and 151st

- ^ Moore, Los de la Calle ... p. 179.

- ↑ Forteza, Els descendents ... p. 74.

- ↑ Font, La fe vençuda. Pp. 154-158.

- ↑ In relation to the different perceptions of the current degree of liquidation, I refer to the transcription of the Round Table Els xuetas: la pervivencia d'una identitat , Segell , No. 1, pp. 193–212.

- ↑ Moore, Los de la Calle… pp. 173–175.

- ↑ In fact, the same Forteza, together with Gabriel Cortès Cortès , both have already done it with the book Reconciliados y Relajados , which appeared anonymously in Barcelona in 1946 in an edition of only 200 copies.

- ↑ Riera, Els xuetes…. Pp. 145-200.

- ↑ Font, La fe vençuda… pp. 163–168.

- ↑ Font, La fe vençuda ... p. 163.

- ↑ For example at the end of this article: Hace 57 años que me “ comí un rabino ”. Retrieved January 31, 2010 (Spanish).

- ↑ Cayetano Martí Valls. Retrieved January 31, 2010 (Spanish).

- ↑ Los xuetas mallorquines. Quince siglos de racismo. P. 73.

- ↑ Pere A. Salvà i Margalida Gamundí, UIB, 1997; quoted in the journal Segell No. 1, p. 199.

- ↑ ARCA Llegat Jueu . Retrieved January 31, 2010 (Catalan, Spanish).

- ^ Memòria del Carrer . Retrieved January 31, 2010 (Catalan, Spanish, English).

- ↑ Sail . Retrieved January 31, 2010 .

- ↑ Red de Juderías. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on December 18, 2010 ; Retrieved January 31, 2010 (Spanish). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Pérez, Anales… , in detail, Laub, El mito triunfante. Pp. 256–259 and Font, La fe vençuda… pp. 62 and 107, Planas, Els malnoms… pp. 16 and 17.

- ↑ In the eponymous, autobiographical tale in chap. 4, pp. 37-40; Spelling also "Chueta". The narrative from 1913, the author died prematurely 3 years later, which seems unfinished on the whole, conveys anti-Jewish interpretations to the Xuetas. Darío notices her isolation from the rest of the islanders and the propaganda of marriage bans with non-Xuetas within the group.