Sandra Day O'Connor: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

m BOT - Reverted all consecutive edits by Yonee {possible vandalism}. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox Judge |

|||

| name = Sandra Day O'Connor |

|||

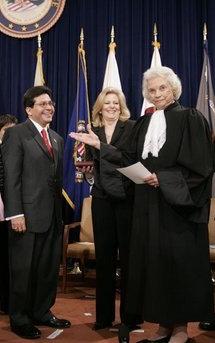

| image = O'connor, Sandra.jpg |

|||

| imagesize = |

|||

| caption = |

|||

| office = [[Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States|Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court]] |

|||

| termstart = [[September 25]] [[1981]] |

|||

| termend = [[January 31]] [[2006]] |

|||

| nominator = [[Ronald Reagan]] |

|||

| appointer = |

|||

| predecessor = [[Potter Stewart]] |

|||

| successor = [[Samuel Alito]] |

|||

| office3 = [[Arizona State Senate|Arizona State Senator]] |

|||

| termstart3 = [[1969]] |

|||

| termend3 = [[1975]] |

|||

| nominator3 = |

|||

| appointer3 = |

|||

| predecessor3 = |

|||

| successor3 = |

|||

| office2 = [[Arizona State Senate|Arizona State Senate Majority Leader]]<br>[[Arizona State Senate|Arizona State Senate Republican Leader]] |

|||

| termstart2 = [[1973]] |

|||

| termend2 = [[1975]] |

|||

| birthdate = {{birth date and age|1930|03|26}} |

|||

| birthplace = [[El Paso, Texas|El Paso]], [[Texas]] |

|||

| deathdate = |

|||

| deathplace = |

|||

| spouse = John Jay O'Connor, III |

|||

| alma_mater = [[Stanford University]] |

|||

| religion = [[Episcopal Church in the United States of America|Episcopalian]] |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Sandra Day O'Connor''' (born [[March 26]] [[1930]]) is an [[United States|American]] [[jurist]] who was the first woman to serve as an [[Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States|Associate Justice]] of the [[Supreme Court of the United States]]. She served from 1981 to 2006. Although she was considered a [[strict constructionist]], her case-by-case approach to [[jurisprudence]] and her relatively moderate political views made her the crucial [[swing vote]] of the Court for many of her final years on the bench. She still objected to that characterization because she felt it painted her as an unprincipled jurist. In 2001, ''[[Ladies' Home Journal]]'' ranked her as the second most powerful woman in America.<ref>{{cite news |

'''Sandra Day O'Connor''' (born [[March 26]] [[1930]]) is an [[United States|American]] [[jurist]] who was the first woman to serve as an [[Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States|Associate Justice]] of the [[Supreme Court of the United States]]. She served from 1981 to 2006. Although she was considered a [[strict constructionist]], her case-by-case approach to [[jurisprudence]] and her relatively moderate political views made her the crucial [[swing vote]] of the Court for many of her final years on the bench. She still objected to that characterization because she felt it painted her as an unprincipled jurist. In 2001, ''[[Ladies' Home Journal]]'' ranked her as the second most powerful woman in America.<ref>{{cite news |

||

| Line 43: | Line 73: | ||

In several speeches broadcast nationally on [[C-SPAN]], she mentioned feeling some relief from the media clamor when [[Ruth Bader Ginsburg]] joined her on the court in 1993. |

In several speeches broadcast nationally on [[C-SPAN]], she mentioned feeling some relief from the media clamor when [[Ruth Bader Ginsburg]] joined her on the court in 1993. |

||

===Presence on the Court=== |

|||

In 1985, at a Washington Press Club dinner, an intoxicated [[Washington Redskins]] player ([[John Riggins]]) drew widespread scorn<ref>[http://www.timesdispatch.com/servlet/Satellite?pagename=RTD/MGArticle/RTD_BasicArticle&c=MGArticle&cid=1031783618415 "Riggins' uncourtly words created no hard feelings"], ''TimesDispatch,'' November 18, 2005.</ref> when he told O'Connor: "Come on, Sandy Baby, loosen up. You're too tight," then passed out on the floor. The next day, the women with whom she shared an early morning exercise class presented her with a T-shirt that read: "Loosen up at the Supreme Court." She apparently bore him no ill will; years later, when he made his acting debut at a local playhouse, she gave him a dozen roses on opening night. O'Connor made her own brief foray into acting one night in 1996 with a surprise appearance as Queen Isabel in a Shakespeare Theatre production of ''[[Henry V (play)|Henry V]]''. |

|||

In 1989, a letter O'Connor wrote regarding three Court rulings on [[Christianity|Christian]] heritage was used by a group of conservative Arizona Republicans in their claim that America was a "Christian nation". O'Connor, an [[Episcopal Church in the United States of America|Episcopalian]], said, "It was not my intention to express a personal view on the subject of the inquiry." |

|||

=== Supreme Court jurisprudence === |

=== Supreme Court jurisprudence === |

||

| Line 74: | Line 109: | ||

| accessdate = 2007-04-26 |

| accessdate = 2007-04-26 |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

==== Abortion ==== |

|||

O'Connor's rulings on the issue of abortion were those that were perhaps most widely considered controversial. In her confirmation hearings and early days on the court, she was carefully ambiguous on the issue, as some conservatives questioned her anti-abortion credentials on the basis of certain of her votes in the Arizona legislature. O'Connor generally dissented from opinions in the 1980s which took an expansive view of ''Roe v. Wade'' and criticized that decision's "trimester approach" sharply in her dissent in 1983's ''Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health''. |

|||

In ''[[Planned Parenthood v. Casey]]'', O'Connor's opinion introduced a new test that reined in the unrestricted freedom from regulation during the first trimester as proscribed by ''[[Roe v. Wade]]''. Whereas before the regulatory powers of the State could not intervene so early in the pregnancy, O'Connor opened a regulatory portal where a State could enact measures so long as they did not place an "undue burden" on a woman's right to an abortion. |

|||

==== Foreign law ==== |

==== Foreign law ==== |

||

| Line 186: | Line 226: | ||

<!-- Link farms --> |

<!-- Link farms --> |

||

{{sandradayoconnoropinions}} |

|||

{{start U.S. Supreme Court composition| CJ=[[Warren E. Burger|Burger]]| }} |

|||

{{U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan|cj=Warren Earl Burger|years=1969–1986| }} |

|||

{{U.S. Supreme Court composition 1981-1986}} |

|||

{{U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ| CJ=[[William Rehnquist|Rehnquist]]| }} |

|||

{{U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan|cj=William Hubbs Rehnquist|years=1986–2005| }} |

|||

{{U.S. Supreme Court composition 1986-1987}} |

|||

{{U.S. Supreme Court composition 1988-1990}} |

|||

{{U.S. Supreme Court composition 1990-1991}} |

|||

{{U.S. Supreme Court composition 1991-1993}} |

|||

{{U.S. Supreme Court composition 1993-1994}} |

|||

{{U.S. Supreme Court composition 1994-2005}} |

|||

{{U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ| CJ=[[John Glover Roberts, Jr.|Roberts]]| }} |

|||

{{U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan|cj=John Glover Roberts, Jr.|years=2005–current| }} |

|||

{{U.S. Supreme Court composition 2005-2006}} |

|||

{{end U.S. Supreme Court composition}} |

|||

{{ISG}} |

{{ISG}} |

||

| Line 199: | Line 256: | ||

|PLACE OF DEATH= |

|PLACE OF DEATH= |

||

}} |

}} |

||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Oconnor, Sandra Day}} |

|||

[[Category:1930 births]] |

|||

[[Category:Living people]] |

|||

[[Category:American Episcopalians]] |

|||

[[Category:Arizona lawyers]] |

|||

[[Category:Arizona State Senators]] |

|||

[[Category:People from El Paso, Texas]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Phoenix, Arizona]] |

|||

[[Category:Prosecutors]] |

|||

[[Category:Rockefeller Foundation]] |

|||

[[Category:Stanford University alumni]] |

|||

[[Category:United States Supreme Court justices]] |

|||

[[Category:Women judges]] |

|||

<!-- Interwiki --> |

<!-- Interwiki --> |

||

[[da:Sandra Day O'Connor]] |

|||

[[pdc:Sandra Day O'Connor]] |

|||

[[de:Sandra Day O’Connor]] |

|||

[[es:Sandra Day O'Connor]] |

|||

[[eo:Sandra Day O'Connor]] |

|||

[[fr:Sandra Day O'Connor]] |

|||

[[he:סנדרה דיי או'קונור]] |

|||

[[mr:सांड्रा डे ओ'कॉनोर]] |

|||

[[nl:Sandra Day O'Connor]] |

|||

[[pl:Sandra Day O'Connor]] |

|||

[[pt:Sandra Day O'Connor]] |

|||

[[ro:Sandra Day O'Connor]] |

|||

[[simple:Sandra Day O'Connor]] |

|||

[[sv:Sandra Day O'Connor]] |

|||

Revision as of 15:14, 12 January 2008

Sandra Day O'Connor | |

|---|---|

| File:O'connor, Sandra.jpg | |

| Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court | |

| In office September 25 1981 – January 31 2006 | |

| Nominated by | Ronald Reagan |

| Preceded by | Potter Stewart |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Alito |

| Arizona State Senate Majority Leader Arizona State Senate Republican Leader | |

| In office 1973–1975 | |

| Arizona State Senator | |

| In office 1969–1975 | |

| Personal details | |

| Spouse(s) | John Jay O'Connor, III |

| Alma mater | Stanford University |

Sandra Day O'Connor (born March 26 1930) is an American jurist who was the first woman to serve as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. She served from 1981 to 2006. Although she was considered a strict constructionist, her case-by-case approach to jurisprudence and her relatively moderate political views made her the crucial swing vote of the Court for many of her final years on the bench. She still objected to that characterization because she felt it painted her as an unprincipled jurist. In 2001, Ladies' Home Journal ranked her as the second most powerful woman in America.[1] In 2004 and 2005 Forbes Magazine listed her as the sixth and thirty sixth most powerful woman in the world, respectively; the only American women preceding her on the list were National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, New York Senator and former First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, and First Lady Laura Welch Bush.[2]

Prior to joining the Supreme Court, she was a politician and jurist in Arizona.[3] She was nominated to the Court by President Ronald Reagan and served for over twenty-four years. On July 12005, she announced her intention to retire effective upon the confirmation of her successor. Justice Samuel Alito, nominated to take her seat in October 2005, received confirmation on January 31 2006. She is currently the Chancellor of the College of William and Mary.

Personal life and education

O'Connor was born Sandra Day to Harry Alfred Day (a rancher) and Ada Mae Wilkey.[4] She grew up on a cattle ranch in the southeastern Arizona town of Duncan. She later wrote a book with her brother, H. Alan Day, titled Lazy B : Growing up on a Cattle Ranch in the American Southwest about her childhood experiences on the ranch. For schooling, she lived in El Paso with her maternal grandmother, and attended the Radford school for girls and Stephen F. Austin High School.

O'Connor attended Stanford University, where she received her B.A. in economics in 1950. She continued at the Stanford Law School for her LL.B, serving on the Stanford Law Review, and graduating toward the top of a class of 102, of which future Chief Justice William Rehnquist was valedictorian. O'Connor briefly dated Rehnquist during this time.[5]

In 1952 she married John Jay O'Connor III, whom she had met in law school, and with whom she has three sons: Scott, Brian, and Jay. John O'Connor has suffered from Alzheimer's disease for over 17 years and Sandra O'Connor has placed many of her efforts recently into creating more awareness about the disease. In November 2007, CNN reported that her family's situation has been made more difficult as, due to memory loss, her husband has formed new personal attachments in the institution where he now lives while not fully recalling his life-long family connections.[6]. On Sunday, November 18, 2007, New York Times reported in an article titled Seized by Alzheimer’s, Then Love[7], that she is relieved to see her husband of 55 years so content.

Early career

In spite of her accomplishments at law school, no law firm in California was willing to hire her as a lawyer, although one firm did offer her a position as a legal secretary. She therefore turned to public service, taking a position as Deputy County Attorney of San Mateo County, California from 1952–1953 and as a civilian attorney for Quartermaster Market Center, Frankfurt, Germany from 1954–1957. From 1958–1960, she practiced law in the Maryvale area of the Phoenix metropolitan area, and served as Assistant Attorney General of Arizona from 1965–1969.

In 1969 she was appointed to the Arizona State Senate and was subsequently re-elected as a Republican to two two-year terms. In 1973, she was elected majority leader.

In 1975, she was elected judge of the Maricopa County Superior Court and served until 1979, when she was appointed to the Arizona Court of Appeals by Democratic governor Bruce Babbitt. During her time in Arizona state government, she served in all three branches.

Supreme Court career

Appointment

On July 7 1981, President Reagan, who had pledged during the 1980 presidential campaign to appoint the first woman to the Supreme Court, nominated her as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, replacing the retiring Potter Stewart. O'Connor was confirmed by the Senate 99–0 on September 21 and took her seat September 25. In her first year on the Court, O'Connor received over sixty thousand letters from the public, more than any other justice in history.

O'Connor was unprepared for the intense scrutiny which came with being the first woman on the Court, but she learned to handle the attention with good humor. For example: In response to a New York Times editorial which mentioned the "nine old men" of the Supreme Court, the self-styled FWOTSC (the First Woman On The Supreme Court) sent a pithy letter to the editor:

- "I noticed the following ....:

- Is no Washington name exempt from shorthand? One, maybe. The Chief Magistrate responsible for executing the laws is sometimes called the POTUS [the President Of The United States].

- The nine men who interpret them are often the SCOTUS [the Supreme Court Of The United States].

- The people who enact them are still, for better or worse, Congress.

- "According to the information available to me, and which I had assumed was generally available, for over two years now SCOTUS has not consisted of nine men. If you have any contradictory information, I would be grateful if you would forward it as I am sure the POTUS, the SCOTUS and the undersigned (the FWOTSC) would be most interested in seeing it."

- -- SANDRA D. O'CONNOR, Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, October 12, 1983[8]

In several speeches broadcast nationally on C-SPAN, she mentioned feeling some relief from the media clamor when Ruth Bader Ginsburg joined her on the court in 1993.

Presence on the Court

In 1985, at a Washington Press Club dinner, an intoxicated Washington Redskins player (John Riggins) drew widespread scorn[9] when he told O'Connor: "Come on, Sandy Baby, loosen up. You're too tight," then passed out on the floor. The next day, the women with whom she shared an early morning exercise class presented her with a T-shirt that read: "Loosen up at the Supreme Court." She apparently bore him no ill will; years later, when he made his acting debut at a local playhouse, she gave him a dozen roses on opening night. O'Connor made her own brief foray into acting one night in 1996 with a surprise appearance as Queen Isabel in a Shakespeare Theatre production of Henry V.

In 1989, a letter O'Connor wrote regarding three Court rulings on Christian heritage was used by a group of conservative Arizona Republicans in their claim that America was a "Christian nation". O'Connor, an Episcopalian, said, "It was not my intention to express a personal view on the subject of the inquiry."

Supreme Court jurisprudence

Sandra O'Connor was part of the federalism movement and approached each case as narrowly as possible, avoiding generalizations that might later "paint her into a corner" for future cases. Initially, she seemed as conservative as Rehnquist but seemed to moderate over the years. Many critics of her tenure on the bench pointed out that her case-by-case approach to jurisprudence allowed her to make arbitrary decisions and shift her principles according to political expediency. Although she formed part of the conservative axis during the later years of the Burger Court, with the departure of the last members of the liberal Warren Court, she was later regarded as occupying the ideological center. It was both O'Connor's dedication to asserting her judicial power over that of other federal institutions and her pragmatic circumspection that gave her a deciding centrist vote for many of the Rehnquist Court's cases.

Here are just some of the cases in which O'Connor was the deciding vote:

- McConnell v. FEC, 540 U.S. 93 (2003)

- This was the ruling that upheld the constitutionality of most of the McCain-Feingold campaign finance bill regulating "soft money" contributions.

- Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003) and Gratz v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 244 (2003)

- O'Connor wrote the opinion of the court in Grutter and joined the majority in Gratz. In this pair of cases, the University of Michigan's undergraduate admissions program was held to have engaged in unconstitutional reverse discrimination, but the more limited type of affirmative action in the University of Michigan Law School's admissions program was held to have been constitutional.

- Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, 536 U.S. 639 (2002)

- O'Connor joined the majority holding that the use of school vouchers for religious schools did not violate the First Amendment's Establishment Clause.

- Boy Scouts of America v. Dale, 530 U.S. 640 (2000)

- O'Connor joined the majority in holding that New Jersey violated the Boy Scouts' freedom of association by prohibiting it from discriminating against its troop leaders on the basis of sexual orientation.

- United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549 (1995)

- O'Connor joined a majority holding unconstitutional Gun-Free School Zones Act as beyond Congress's Commerce Clause power.

On December 12, 2000, O'Connor joined with four other (ruling to stop the ongoing Florida recount) and four other (ruling to allow no further recounts) justices to rule on the Bush v. Gore case that ceased challenges to the results of the 2000 election. Some charged that the Supreme Court interceded unfairly in a political issue. Others noted that the Court specifically restricted the precedent-setting effect of the decision by holding, "Our consideration is limited to the present circumstances, for the problem of equal protection in election processes generally presents many complexities." O'Connor was seen as the ultimate swing vote in 9 member Supreme Court.

Justice O'Connor played an important role in other notable cases, such as:

- Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, 492 U.S. 490 (1989)

- This decision held that state regulation of abortion was constitutional if it provided exceptions for the health of the mother and if it didn't ban abortions contrary to the trimester regime of Roe v. Wade. Although O'Connor joined the majority, which also included Rehnquist, Scalia, Kennedy, and White, in a concurring opinion she refused to explicitly overturn Roe.

- Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003)

- O'Connor wrote a concurring opinion contending that state laws that prohibited homosexual sodomy, but not heterosexual sodomy, violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Although she agreed with the majority in holding such laws unconstitutional, she did not join in the opinion that they violated the substantive due process afforded by the Due Process Clause. Under a ruling under the Equal Protection Clause, states could still prohibit sodomy, provided they prohibited both homosexual sodomy and heterosexual sodomy.

On February 22, 2005, with Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justice John Paul Stevens (who was senior to her) absent, O'Connor presided over oral arguments in the case of Kelo v. City of New London, becoming the first woman to preside over an oral argument before the Supreme Court.

Critique

O'Connor's case-by-case approach routinely placed her in the center of the court, and drew both criticism and praise. Washington Post conservative columnist Charles Krauthammer, for instance, described her as lacking a judicial philosophy and instead displaying "political positioning embedded in a social agenda."[10] Another conservative commentator, Ramesh Ponnuru, wrote that, though O'Connor "has voted reasonably well" from a conservative standpoint, her tendency to issue very case-specific rulings "undermines the predictability of the law and aggrandizes the judicial role."[11]

In contrast, Willamette University College of Law Professor Steven Green, who served for nine years as general counsel for Americans United for Separation of Church and State and has argued before the Court numerous times stated, "She was a moderating voice on the court and was very hesitant to expand the law in either direction." Green also noted that, unlike some other Supreme Court justices, O'Connor "seemed to look at each case with an open mind."[12]

Abortion

O'Connor's rulings on the issue of abortion were those that were perhaps most widely considered controversial. In her confirmation hearings and early days on the court, she was carefully ambiguous on the issue, as some conservatives questioned her anti-abortion credentials on the basis of certain of her votes in the Arizona legislature. O'Connor generally dissented from opinions in the 1980s which took an expansive view of Roe v. Wade and criticized that decision's "trimester approach" sharply in her dissent in 1983's Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health.

In Planned Parenthood v. Casey, O'Connor's opinion introduced a new test that reined in the unrestricted freedom from regulation during the first trimester as proscribed by Roe v. Wade. Whereas before the regulatory powers of the State could not intervene so early in the pregnancy, O'Connor opened a regulatory portal where a State could enact measures so long as they did not place an "undue burden" on a woman's right to an abortion.

Foreign law

O'Connor was a vigorous defender of the citing of foreign laws in judicial decisions. In a well-publicized October 28 2003 speech at the Southern Center for International Studies, O'Connor said:

- The impressions we create in this world are important and can leave their mark... There is talk today about the "internationalization of legal relations." We are already seeing this in American courts, and should see it increasingly in the future. This does not mean, of course, that our courts can or should abandon their character as domestic institutions. But conclusions reached by other countries and by the international community, although not formally binding upon our decisions, should at times constitute persuasive authority in American courts—what is sometimes called "transjudicialism".[13]

In the speech she noted the 2002 Supreme Court case Atkins v. Virginia, in which the majority decision (which included her) cited disapproval of the death penalty in Europe as part of its argument.

This speech, and the general concept of relying on foreign law and opinion, was widely criticized by conservatives.[14] In May 2004, the House of Representatives responded by passing a non-binding resolution, the "Reaffirmation of American Independence Resolution", stating that "U.S. judicial decisions should not be based on any foreign laws, court decisions, or pronouncements of foreign governments unless they are relevant to determining the meaning of American constitutional and statutory law."[15]

O'Connor once quoted the constitution of the Middle Eastern nation of Bahrain, which states that "no authority shall prevail over the judgement of a judge, and under no circumstances may the course of justice be interfered with." Further, "It is in everyone's interest to foster the rule-of-law evolution." O'Connor proposed that such ideas be taught in American law schools, high schools and universitieses. Critics contend that such thinking is contrary to the U.S. Constitution and establishes a rule of man, rather than law.[16]

Retirement

Justice O'Connor was successfully treated for breast cancer in 1988 (she also had her appendix removed that year). One side effect of this experience was that there was perennial speculation over the next seventeen years that she might retire from the Court.

On December 12 2000, the Wall Street Journal reported O'Connor was reluctant to retire with a Democrat in office:

At an Election Night party at the Washington, D.C. home of Mary Ann Stoessel, widow of former Ambassador Walter Stoessel, the justice's husband, John O'Connor, mentioned to others her desire to step down, according to three witnesses. But Mr. O'Connor said his wife would be reluctant to retire if a Democrat were in the White House and would choose her replacement. Justice O'Connor declined to comment.[17][18]

By 2005, the membership of the Supreme Court had been static for eleven years, the second longest period without a change in the Court's composition in American history. Chief Justice William Rehnquist was widely expected to be the first justice to retire during President George W. Bush's term, due to his age and his battle with cancer. However, on July 1 2005 it was O'Connor who announced her retirement. In her letter to President Bush she stated that her retirement from active service would take effect upon the confirmation of her successor.

On July 19, President Bush nominated D.C. Circuit Judge John G. Roberts, Jr. to succeed Justice O'Connor, answering months of speculation as to Bush Supreme Court candidates. O'Connor heard the news over the car radio on the way back from a fishing trip. She felt he was an excellent and highly qualified choice—he had argued numerous cases before the Court during her tenure—but was somewhat disappointed her replacement was not a woman.

On July 21, O'Connor spoke[19] to a 9th U.S. Circuit conference and blamed the televising of Senate Judiciary Committee hearings for escalated conflicts over judges. She expressed sadness over attacks on the independent judiciary, and praised President Reagan for opening doors for women.

O'Connor had expected to leave the high court before the start of the next term on October 3 2005. However, on September 3, Rehnquist died (O'Connor spoke at his funeral). Two days later, President Bush withdrew Roberts as his nominee for O'Connor's seat and instead appointed him to fill the vacant office of Chief Justice. O'Connor agreed to stay on the court until her replacement was confirmed. On October 3, President Bush nominated White House Counsel Harriet Miers to replace O'Connor. On October 27, Miers asked President Bush to withdraw her nomination; Bush accepted her request later the same day. On October 31, President Bush nominated Third Circuit Judge Samuel Alito to replace O'Connor; Alito was confirmed and sworn in on January 31 2006.

Her last opinion, Ayotte v. Planned Parenthood of New England, written for a unanimous court, was a procedural decision that involved abortion.

She has stated that after leaving the high court, she plans to travel, spend time with family, and, due to her fear of the attacks on judges by legislators, will work with the American Bar Association on a commission to help explain the separation of powers and the role of judges. She has also announced that she is working on a new book, which will focus on the early history of the Supreme Court. She is currently a trustee on the board of the Rockefeller Foundation. She would have preferred to stay on the Supreme Court for several more years until she was ill and "really in bad shape" but stepped down to spend more time with her husband, who has been diagnosed with early stage Alzheimer's Disease. O'Connor, who is still physically and mentally fit, said it was her plan to follow the tradition of previous justices, who enjoy lifetime appointments. "Most of them get ill and are really in bad shape, which I would've done at the end of the day myself, I suppose, except my husband was ill and I needed to take action there".[20]

Post-Supreme Court career

Commentary

On March 9 2006, during a speech at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., O'Connor said some political attacks on the independence of the courts pose a direct threat to the constitutional freedoms of Americans. She said any reform of system is debatable as long as it is not motivated by "nakedly partisan reasoning" retaliation because congressmen or senators dislike the result of the cases. Courts interpret the law as it was written, not as the congressmen might have wished it was written, and "it takes a lot of degeneration before a country falls into dictatorship, but we should avoid these ends by avoiding these beginnings."

On September 19 2006, Justice O'Connor echoed her concerns for an independent judiciary during the Dedication Address at the Elon University School of Law.

On September 27 2006, Justice O'Connor published an op-ed in Wall Street Journal titled "The Threat to Judicial Independence", in which she decried recent efforts to curtail the independence of the judiciary (such as South Dakota's J.A.I.L. 4 Judges initiative and the attempts by some members of Congress to strip the federal judiciary of its jurisdictional ability to hear certain Constitutional claims). The next day, Justice O'Connor co-hosted and spoke at a conference at Georgetown University Law Center titled "Fair and Independent Courts: A Conference on the State of the Judiciary."[21]

Judge William H. Pryor, Jr., a conservative jurist, has criticized O'Connor's speeches and op-eds for hyperbole and factual inaccuracy, based in part on O'Connor's opinions as to whether judges face a rougher time in the public eye today than in the past. [22][23]

On November 7, 2007, at a conference on her landmark opinion in Strickland v. Washington sponsored by the Constitution Project, O'Connor urged the creation of a system for "merit selection for judges." She also highlighted the lack of proper legal representation for many of the poorest defendants.[24]

Activities and memberships

As a Retired Supreme Court Justice (roughly equivalent to senior status for judges of lower federal courts), Justice O'Connor is entitled to receive a full salary, maintain a staffed office with at least one law clerk, and to hear cases on a part-time basis in the federal District Courts and Courts of Appeals.

On October 4, 2005, President Gene Nichol of the College of William and Mary announced that O'Connor had accepted[25] the largely ceremonial role of becoming the 23rd Chancellor of the College, replacing Henry Kissinger, and following in the position held by Margaret Thatcher, Chief Justice Warren Burger, and President George Washington. The Investiture Ceremony was held April 7, 2006. O'Connor continues to make semi-regular visits to the College, and has played a notably more active role than her predecessors.

- In 2005, she wrote a children's book titled Chico (ISBN 0-525-47452-8), which gives an autobiographical description of her childhood.

Justice O'Connor was a member of the 2006 Iraq Study Group, appointed by the United States Congress.[26]

On May 15, 2006, O'Connor gave the commencement address at the William and Mary School of Law, where she said that judicial independence is "under serious attack at both the state and national level."[27]

As of Spring 2006, Justice O'Connor teaches a two week course called "The Supreme Court" at the University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of Law every Spring semester.

In October 2006, Justice O'Connor sat as a member of panels of the United States Courts of Appeals for the Second, Eighth, and Ninth Circuits, to hear arguments in one day's cases in each court.[28]

The retired Justice chaired the Jamestown 2007 celebration at Jamestown, Virginia, which commemorated the 400th anniversary of the founding of the Jamestown Settlement in 1607. Her appearances in Jamestown dovetailed with her appearances and speeches as chancellor at the nearby College of William and Mary.

Justice O'Connor and W. Scott Bales are currently (Fall 2007) teaching a course at Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law at Arizona State University.

Awards and honors

- In 2002, O'Connor was inducted into the National Cowgirl Hall of Fame.[29]

- On September 8, 2004, Redwood City, California dedicated the courtroom of the renovated historical courthouse (now a museum) to O'Connor.[30]

- For her commitment to the ideals of "Duty, Honor, Country," she was awarded the prestigious Sylvanus Thayer Award by the United States Military Academy in 2005, becoming only the third woman to receive the award.

- On October 18 2005, Justice O'Connor was appointed Grand Marshal of the Tournament of Roses. She participated in the 117th annual Tournament of Roses Parade in Pasadena, California on January 2 2006 and started the 92nd Rose Bowl game with a coin toss on January 4. Coincidentally, the parade was conducted in heavy rain for the first time since 1955, when the Grand Marshal had been Chief Justice Earl Warren.

- On April 5, 2006, Arizona State University renamed its law school the Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law.[31]

- On May 22 2006, Yale University granted Justice O'Connor an honorary doctoral degree at Yale's 305th commencement.

- On September 19 2006, Justice O'Connor delivered the Dedication Address for the Elon University School of Law and accept an Honorary Doctor of Laws degree. Earlier that day, she delivered the Fall Convocation Address at Elon University, where she accepted a Doctor of Laws degree.

Other facts and information

This article contains a list of miscellaneous information. (June 2007) |

- In 1990, Justice O'Connor was present, along with Warren Burger at the dedication of the Warren Burger Law Library at Burger's alma mater, William Mitchell College of Law.

- O'Connor is an avid golfer who scored a hole-in-one in 2000 at the Paradise Valley Country Club in Arizona.[32][33]

- In 2004, she gave a reading during the state funeral of Ronald Reagan.

References

- Steve Lash. "Trailblazer for women determined big issues". Tennesseean.com. Retrieved July 22.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - The Pointer View. "Academy names O'Connor as this year's Thayer Award recipient". pointerview.com. Retrieved October 19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - E.J. Montini. "Rehnquist is No. 1, O'Connor is No. 3, Baloney is No. 2.", Arizona Republic, (July 12, 2005).[1]

- Sandra Day O'Connor and H. Alan Day (2002). Lazy B: Growing Up on a Cattle Ranch in the American Southwest. Random House. ISBN 0-375-50724-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)

Notes

- ^ John McCaslin (November 7 2001). ""McCaslin's Beltway Beat: Power Weomen". Townhall.com. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The World's Most Powerful Women". Forbes magazine. August 31 2006. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Sandra Day O'Connor, Judges of the United States Courts, Federal Judicial Center". Retrieved March 21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.oyez.org/oyez/resource/legal_entity/102/print

- ^ http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,161325,00.html

- ^ CNN Newsroom, Cable News Network, 1:45 PM on November 14, 2007.

- ^ 'Seized by Alzheimer’s, Then Love", New York Times, November 18, 2007.

- ^ "High Court's '9 Men' Were a Surprise to One", New York Times, October 12, 1983 re: (First Woman On The Supreme Court); Safire, "On Language' Potus and Flotus", New York Times, October 12, 1997. Retrieved 7 Dec 2007

- ^ "Riggins' uncourtly words created no hard feelings", TimesDispatch, November 18, 2005.

- ^ Krauthammer, Charles. "Philosophy for a Judge". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Ponnuru, Ramesh (June 30, 2003). "Sandra's Day". National Review. Retrieved March 18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Smythe, Barbara. "Retired But Remembered: Oregon lawyers reminisce about Justice Sandra Day O'Connor". Retrieved 2007-04-26.

- ^ Remarks at the Southern Center for International Studies, Sandra Day O'Connor, October 28, 2003

- ^ Phyllis Schlafly (May 2005). "Is Relying on Foreign Law Impeachable?". The Phyllis Schlafly Report.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Reaffirmation of American Independence Resolution Approved", May 13, 2004

- ^ Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, Remarks before the Southern Center for International Law Studies, Keynote Address, October 28, 2003

- ^ "Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics, The: Conflicts of interest in Bush v. Gore: Did some justices vote illegally?". Retrieved November 18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "TIME Pacific : Can the Court Recover? : December 25, 2000 : NO. 51". Retrieved November 18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "O'Connor Saddened by Attacks on Judiciary". Retrieved November 18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Associated Press (February 5, 2007). "Former Justice O'Connor:'I Would Have Stayed Longer'".

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Greg Langlois and Anne Cassidy. "Fair and Independent Courts: A Conference on the State of the Judiciary" (Press release). Georgetown University Law Center. Retrieved 2006-11-11.

- ^ "'Neither Force Nor Will, But Merely Judgment'", Wall Street Journal, 4 Oct 2006

- ^ "Judge Pryor on Judicial Independence", Harvard Law Record, 15 Mar 2007

- ^ "Justice O'Connor's Wish: a Wand, not a Gavel", U.S. News & World Report, November 7, 2007.

- ^ "College of William and Mary announcement of O'Connor's appointment to Chancellor post". Retrieved November 18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Iraq Study Group Members". Retrieved November 10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Brian Whitson. "Maintain Judicial Independence O'Connor Tells Law Graduates". Retrieved 9-19-07.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Mulcahy, Ned (2006-10-07). "Paper Chase: O'Connor to hear Second Circuit cases". Jurist. Retrieved 2006-11-11.

- ^ "Cowgirl Hall of Fame". Retrieved November 18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Sanda Day O'Connor at courthouse

- ^ "ASU names College of Law after O'Connor". ASU Insight. 2006-04-05. Retrieved 2007-09-19.

- ^ "TIME Magazine Archive Article — Off The Bench? — Feb. 26, 2001". Retrieved November 18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Digest.com - Will Augusta come calling?". Retrieved November 18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)

External links

- General biographical information

- Additional information

-

Works related to Works by Sandra Day O'Connor at Wikisource

Works related to Works by Sandra Day O'Connor at Wikisource- Read Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding Justice O'Connor

- "O'Connor not bothered by delayed retirement.", Associated Press September 28, 2005.

- "Sandra Day O'Connor prepares for final days on Supreme Court.", Associated Press September 19, 2005.

- Cases in which O'Connor has been the deciding vote (July 1, 2005)

- Farewell comments from her fellow justices (July 1, 2005)

- Centrist justice sought 'social stability'

- Yahoo!: Sandra Day O'Connor directory category

Template:Start U.S. Supreme Court composition Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1981-1986 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1986-1987 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1988-1990 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1990-1991 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1991-1993 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1993-1994 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1994-2005 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 2005-2006 Template:End U.S. Supreme Court composition