Shapeshifting: Difference between revisions

m →Forms of Shapeshifting: Spacing. |

m →Forms of Shapeshifting: typos |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

===Forms of Shapeshifting=== |

===Forms of Shapeshifting=== |

||

There are many different styles of shapeshifting to be seen. One is the literal bodily alteration where the body physically changes. Depending on what the subject is changing into, the different parts of the body will shift, stretch, compress, and expand. This type of shapeshifting is often against the subject's will and can be a slow and painful process; articles of clothing are usually lost or destroyed, as in the case of the [[werewolf]], although there are |

There are many different styles of shapeshifting to be seen. One is the literal bodily alteration where the body physically changes. Depending on what the subject is changing into, the different parts of the body will shift, stretch, compress, and expand. This type of shapeshifting is often against the subject's will and can be a slow and painful process; articles of clothing are usually lost or destroyed, as in the case of the [[werewolf]], although there are separate cases that can cause the werewolf to transform in the thirdform of shapeshifting(read the third paragraph in this section), or the transformation of Eustace into a dragon in ''[[The Voyage of the Dawn Treader]]'' by C.S. Lewis. |

||

A second style is what can be called the 'fold over'. In this transformation, the subject new flesh forms overtop of their original. In a sense, it is almost as if they are wearing a body over another, and their old form is underneath. In Margaret Weis's ''[[Mistress of Dragons]]'', an evil dragon called Marista steals human hearts and uses them to acquire a human form which she changes into in this way. This form of shapeshifting is most commonly painless but can be traumatic if the change was unintentional, as in the case of Link in the video game [[The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess]], where the hero is transformed into a wolf. Clothing is rarely lost in this process. In retransformation, the form will fold back and the subject will 'crawl' back out. |

A second style is what can be called the 'fold over'. In this transformation, the subject new flesh forms overtop of their original. In a sense, it is almost as if they are wearing a body over another, and their old form is underneath. In Margaret Weis's ''[[Mistress of Dragons]]'', an evil dragon called Marista steals human hearts and uses them to acquire a human form which she changes into in this way. This form of shapeshifting is most commonly painless but can be traumatic if the change was unintentional, as in the case of Link in the video game [[The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess]], where the hero is transformed into a wolf. Clothing is rarely lost in this process. In retransformation, the form will fold back and the subject will 'crawl' back out. |

||

Revision as of 04:19, 5 February 2008

Shapeshifting is a common theme in folklore, as well as in science fiction and fantasy. In its broadest sense, it is a change in the physical form or shape of a person or animal. Other terms include metamorphosis, morphing, transformation, or transmogrification.

There is no settled agreement on the terminology. Still, the most common usages are:

- shapeshifting indicates changes that are temporary[1]

- metamorphosis indicates changes that are lasting[2]

- transformation indicates changes that are externally imposed[3]

Shapeshifting is distinguished from natural processes such as aging or metamorphosis (despite shared use of the term), the body contortions of animals such as the Mimic Octopus, and illusory changes. Instead, shapeshifting involves physical changes such as alterations of age, gender, race, or general appearance or changes between human form and that of an animal, plant, or inanimate object.

Themes in shapeshifting

The most important aspect of shape-shifting, thematically, is whether the transformation is voluntary. Circe transforms intruders to her island into swine, and Ged, in A Wizard of Earthsea, becomes a hawk to escape an evil wizard's stronghold. A werewolf's transformation, driven by internal forces, is as hideous as that which Circe enforces, and when Minerva transforms Cornix into a crow, Ovid put into Cornix's mouth that "the virgin goddess feels pity for a virgin and she helped me" because her new form enabled her to escape rape at Neptune's hands. When a form is taken on involuntarily, the thematic effect is one of confinement and restraint; the person is bound to the new form. In extreme cases, such as petrifaction, the character is entirely disabled. Voluntary forms, on the other hand, are means of escape and liberation; even when the form is not undertaken to effect a literal escape, the abilities specific to the form, or the disguise afforded by it, allow the character to act in a manner previously impossible.

Hence, in fairy tales, a prince who is forced into a bear's shape (as in East of the Sun and West of the Moon) is prisoner, but a princess who takes on a bear's shape to flee (as in The She-Bear) escapes with her new shape.[4]

Shapeshifting may be used as a plot device, as when Puss In Boots tricks the ogre into changing into a mouse so he may eat him; it may also include a symbolic significance, as when the Beast's transformation at the end of Beauty and the Beast indicates Beauty's ability to accept him despite his appearance.[5]

In modern fantasy, more than in folklore, the extent to which the change affects the mind can be important. Poul Anderson, in Operation Chaos, has the werewolf observe that taking on wolf-form can simplify his thoughts. This can be more dangerous in other writers' works; J.K. Rowling observed that a wizard who became a rat had a rat's brain (although the Animagus talent bypasses this problem), and in her Earthsea books, Ursula K. Le Guin depicts an animal form as slowly transforming the wizard's mind, so that the dolphin, or bear, or other creature forgets it was human and can not change back, a voluntary shapeshifting becoming an imprisoning metamorphosis.[6]

Beyond this, the uses of shape-shifting, transformation, and metamorphosis in fiction are as protean as the forms the characters take on. Some are rare — Italo Calvino's "The Canary Prince" is a Rapunzel variant in which shape-shifting is used to gain access to the tower — but others are common motifs.

Forms of Shapeshifting

There are many different styles of shapeshifting to be seen. One is the literal bodily alteration where the body physically changes. Depending on what the subject is changing into, the different parts of the body will shift, stretch, compress, and expand. This type of shapeshifting is often against the subject's will and can be a slow and painful process; articles of clothing are usually lost or destroyed, as in the case of the werewolf, although there are separate cases that can cause the werewolf to transform in the thirdform of shapeshifting(read the third paragraph in this section), or the transformation of Eustace into a dragon in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader by C.S. Lewis.

A second style is what can be called the 'fold over'. In this transformation, the subject new flesh forms overtop of their original. In a sense, it is almost as if they are wearing a body over another, and their old form is underneath. In Margaret Weis's Mistress of Dragons, an evil dragon called Marista steals human hearts and uses them to acquire a human form which she changes into in this way. This form of shapeshifting is most commonly painless but can be traumatic if the change was unintentional, as in the case of Link in the video game The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess, where the hero is transformed into a wolf. Clothing is rarely lost in this process. In retransformation, the form will fold back and the subject will 'crawl' back out.

The third is the fastest and most convenient type of shapeshifting. In this style the subject in a sense has two separate bodies that they can freely switch between. Such being can be found in the Harry Potter series, in which they are known as Animagi. This change is always intentional and won't harm clothing, or any other article on the body. Injuries sustained on either of the bodies usually don't carry onto each other (Animagi in Harry Potter being an exception), although death of one of the forms usually results in the death of both forms and the individual in question. During the shapeshift, there sometimes is a moment when the subject seems to disappear, but this is a very rare moment .

Between the sexes

A particularly noteworthy aspect is where the person changes sex, from female to male, or vice versa. Fiction that makes use of such shape-shifting tends to invoke themes not normally found in other shapeshifting fiction.

It may be merely used as means of disguise: appearing as a woman allows a man to enter situations from which men are forbidden, and vice versa. Zeus disguised himself as Artemis in order to get close enough to Callisto that she could not escape when he turned himself into male form again, and raped her. More innocently, Vertumnus could not woo Pomona on his own; in the form of an old woman, he gained access to her orchard, where he persuaded her to marry him.

In Norse mythology, however, both Odin and Loki taunt each other with having taken the form of females in the Lokasenna. The ultimate proof of this was that they had given birth and had nursed their offspring. It is not known what myths, if any, lie behind the charges against Odin, but Loki had taken the form of a mare and was the mother of Sleipnir.

L. Frank Baum concluded The Marvelous Land of Oz with the revelation that the princess, Ozma, that the characters had been looking for had been turned into a boy while a baby and raised the boy Tip. Tip, one of the characters looking for Ozma, agreed to let himself be changed back into a girl but wished that he could be changed back into a boy if he did not like being a girl; Glinda decreed that he could be changed only into his proper form and, because as a sorceress, she disapproves of and does not perform shapeshifting magic, had it done by the evil witch Mombi, who knew how to do it.[7]

In Greek mythology, Tiresias, who became the blind prophet who helps Jason and the Argonauts, was walking through a forest when he found two snakes in the act of love. He prodded them with a stick and he instantly changed into a woman. He lived as one for many years, married and had children. Years later, he was walking through the same forest, and saw the same snakes doing the same thing. Again he poked them with a stick, and he turned back into a man. Later in his life, he was asked by Zeus which of the two sexes enjoys sex more. Tiresias, speaking from experience, replied that it is woman, and Hera blinded him for telling her husband of the greatest secret of women. Zeus, unable to undo what his wife has done, gave the now blind Tiresias the gift of foresight. Other versions say that it was Zeus who was angered by Tiresias for saying that men did not get the most out of sex and that it was Hera who gave him the gift of foresight to comfort him.

Rumiko Takahashi's manga Ranma 1/2, along with several characters that transform into animals, also features two that transform from male to female. One is the title character, Ranma Saotome, and another is a powerful antagonist, Herb, from late in the series. While some have drawn the conclusion that this constitutes a parody of Japanese gender roles,[8] Takahashi herself has replied that it was a "simple, fun idea," that she "doesn't think in terms of societal agendas," and "thought humans turning into animals might also be fun and marchenhaft."[9]

Punitive changes

In many cases, imposed forms are punitive in nature. This may be a just punishment, the nature of the transformation matching the crime for which it occurs; in other cases, the form is unjustly imposed by an angry and powerful person.

This motif is used in tales from myths to modern fantasy:

- Athena transformed Arachne into a spider for challenging her as a weaver.

- Artemis transformed Actaeon into a stag for spying on her in her bath.

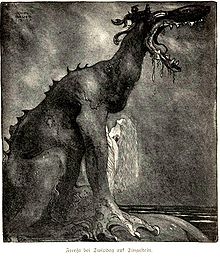

- Odin transformed Svipdag into a dragon because he had angered him.

- In Child ballad 35, Allison Gross, the title witch turned a man into a dragon for refusing to be her lover; this is a motif found in many legends and folktales, of a thwarted lover punishing the refusal with a transformation.[10]

- In some variants of the fairy tales, both The Frog Prince and Beast, of Beauty and the Beast, were transformed as a form of punishment for some transgression.

- In Eglė the Queen of Serpents, Eglė transforms her children and herself into trees as a punishment for betrayal.

- In East of the Sun and West of the Moon, the hero was transformed into a bear by his wicked stepmother, who wished to force him to marry her daughter.[11]

- Circe transformed all intruders into her home. Generally, this is for merely intruding, but in Nathaniel Hawthorne's Tanglewood Tales, "she changes every human being into the brute, beast, or fowl whom he happens most to resemble."

- In George MacDonald's The Princess and Curdie, Curdie is informed that many human beings, by their acts, are slowly turning into beasts; he is given the power to detect the transformation before it is visible, and is assisted by beasts that had been transformed and are working their way back to humanity.[12]

- In The Chronicles of Narnia, Eustace transforms into a dragon,[13] and the war-monger Rabadash into a donkey,[14]. Eustace's transformation is not strictly a punishment - his transformation simply revealing the truth of his human nature. It is reversed after he repents and (through grace) his nature is transformed. Rabadash is given an opportunity to return to human form providing he does so in a public place, so that his former followers will know that he had spent some time as a donkey. He is also warned that, if he ever leaves his capital city again, he will once more become a donkey and this time the transformation will be permanent. After following the instructions to regain his human form, Rabadash never again leads a military campaign ... as to do so would require him to leave his capital city. Also in The Chronicles of Narnia the Dufflepuds are dwarfs who have been transformed into monopods as a punishment.

In mythology, the punishment is often a metamorphosis, and may be origin myths.

In most works of fiction, the changes are usually a temporary transformation. If the punishment was just, the character can often re-gain his form on learning the lesson it instructed him in; if unjust, the restoration is merely dependent on discovering the trick of it.

Transformation chase

In many fairy tales and ballads, as in Child Ballad #44, The Two Magicians or Farmer Weathersky, a magical chase occurs where the pursued endlessly takes on forms in an effort to shake off the pursuer, and the pursuer answers with other shape-shifting, as, a dove is answered with a hawk, and a hare with a greyhound. The pursued may finally succeed in escape or the pursuer in capturing. This appears in legends around the world. In Dapplegrim, this was set as a challenge; if the youth found the transformed princess twice, and hid from her twice, they would marry. The Grimm Brothers fairy tales Foundling-Bird contains this as the bulk of the plot.[15] In Greek mythology, Zeus frequently transformed himself and his love to escape Hera's wrath, or that of the women's fathers, but generally in a simplified form, with only one transformation.[16]

In other variants, the pursued may transform various objects into obstacles, as in the fairy tale "The Master Maid", where the Master Maid transforms a wooden comb into a forest, a lump of salt into a mountain, and a flask of water into a sea. In these tales, the pursued normally escapes after the three obstacles.[17] This obstacle chase is literally found world-wide, in many variants in every region.[18]

In fairy tales of the Aarne-Thompson type 313A, the girl helps the hero flee, one such chase is an integral part of the tale. It can be either a transformation chase (as in The Grateful Prince, King Kojata, Foundling-Bird, Jean, the Soldier, and Eulalie, the Devil's Daughter, or The Two Kings' Children) or an obstacle chase (as in The Battle of the Birds, The White Dove, or The Master Maid).[19]

In a similar effect, a captive may shape-shift in order to break a hold on him. Proteus's shape-shifting was to prevent heroes from forcing information from him.[20] Tam Lin, once seized by Janet, was transformed in her arms by the faeries to keep Janet from taking him, but as he had advised her, she did not let go, and so freed him.[21] The motif of capturing a person by holding him through all forms of transformation is found throughout Europe in folktales.[22]

Patricia A. McKillip made use of this motif at one point in the The Riddle-Master of Hed trilogy: a shapeshifting Earthmaster finally wins its freedom by startling the man holding it.

Another variant was used by T. H. White in The Sword in the Stone, where Merlin and Madam Mim fought a wizards' duel, in which the duelists would endlessly transform until one was in a form that could destroy the other.[23]

Powers

One motif is a shape change in order to obtain abilities in the new form. Berserkers were held to change into wolves and bears in order to fight more effectively. In many cultures, evil magicians could transform into animal shapes and thus skulk about.

In many fairy tales, the hero's talking animal helper proves to be a shapeshifted human being, able to help him in its animal form. In one variation, featured in The Three Enchanted Princes and The Death of Koschei the Deathless, the hero's three sisters have been married to animals. These prove to be shape-shifted men, who aid their brother-in-law in a variant of tale types.[24]

This use, though rare in older fiction, is perhaps the most common in modern fiction. Several superheroes — Beast Boy, Chameleon Boy/Chameleon, Morph, Ben 10, Mystique — have it as their sole power. The Harry Potter series contains both Animagi who can change to a single form and Metamorphmagi who can alter their appearance. Even one episode of the television show " Supernatural " featured a shape-shifter, and a reference that the main characters had hunted shape-shifters before, or at least knew how to. Both the Earthmasters and their opponents in The Riddle-Master of Hed trilogy make extensive use of their shape-shifting abilities for the powers of their new forms.[25]

Even creatures from folklore may regard their other forms as abilities. The werewolf in Poul Anderson's Operation Chaos uses his wolf form to track and to fight, and never suffers from the desire to attack humans so common in legend.[26]

Bildungsroman

A young character may learn of his shape-shifting abilities, and exploring them becomes part of a Bildungsroman. Mavin Manyshaped and her son Peter in Sheri S. Tepper's True Game novels are both shifters, being a subspecies of humans having this power, and in both, the learning of their abilities is a large portion of their growing up.

For a very different effect, T. H. White had Merlin transform Arthur into various animals in The Sword in the Stone, as an educational experience.[27] Although the lessons are very different, the Bildungsroman element is in common.

Needed items

Some shape-shifters are able to change form only if they have some item, usually an article of clothing. Most of these are innocuous creatures — even if they are werewolves. In Bisclavret by Marie de France, a werewolf cannot regain human form without his clothing, but in wolf form does no harm to anyone.

Another such creature is the selkie, which needs its sealskin to regain its form. In "The Great Silkie of Sule Skerry" the (male) selkie seduces a human woman but does no further harm.

The commonest use of this motif, however, is in tales where a man steals the article and forces the shape-shifter, trapped in human form, to become his bride. This lasts until she discovers where he has hidden the article, and she can flee. Selkies feature in these tales. Others include swan maidens and the Japanese Tennin.

Various forms of fairytale fantasy have taken up these creatures and incorporated them into modern day works. Jane Yolen took up the notion of selkie in Greyling and transformed it into a foundling tale.

Usurpation

Some transformations are performed to remove the victim from his place, so that the transformer can usurp it. Bisclaveret's wife steals his clothing and traps him in wolf form because she has a lover. A witch, in The Wonderful Birch, changed a mother into a sheep to take her place, and had the mother slaughtered; when her stepdaughter, with her dead mother's aid, married the king, the witch transformed her into a reindeer so as to put her daughter in the queen's place. In the Korean "Transformation of the Kumiho", a kumiho, a fox with magical powers, transformed itself into an image of the bride, only being detected when her clothing is removed. In Terminator 2: Judgment Day, the T-1000 took the form of John Connor's foster mom to gather information regarding his whereabouts, and later as his biological mother to gain his trust. Changelings take the place of the infant the elves have stolen, and usually resemble it, at least initially; sometimes, this is temporary, so that the child will appear to die, and sometimes the changeling grows up in the child's family.

This may not be so much desire to usurp a specific place as to remove possible rivals, but the intended effect of the removal is much the same. In Brother and Sister, when two children flee their cruel stepmother, she enchants the streams along the way to transform them. While the brother refrains from the first two, which threaten to turn them into tigers and wolves, he is too thirsty at the third, which turns him into a deer. The Six Swans are transformed into swans by their stepmother,[28] as are the Children of Lir in Irish mythology. In The Laidly Worm of Spindleston Heugh, Princess Margaret is transformed into a dragon by her stepmother; her motive sprung, like Snow White's stepmother's, from the comparison of their beauty.[29]

Modern fiction also includes this motif: Mary Stewart's A Walk in Wolf Wood revolves about revealing that one man is an imposter, taking the form of a man who is living as a wolf in the woods, and Patricia A. McKillip has her shapeshifters, in the Riddle-master trilogy, use their forms to take the place of others. The Harry Potter series included both a usurpation by a shape-shifter, and considerable precautions being taken by wizards and witches to attempt to identify such shape-shifters as they arose. In science fiction, "Who Goes There?" by John W. Campbell included a shape-shifting alien that could devour and replace terrestrial life.

While Doppelgängers in folklore were a kind of portent that resembled a person, with no shapeshifting required, in modern fiction and roleplaying games, they are usually depicted as shape-shifters out to usurp someone's place.

This motif can also be used in a similar manner to the Monstrous Bride/Bridegroom theme. A character who falls in love with a usurper (given a justifiable motive for the replacement) can discover the unimportance of appearances beside character. In the Legion of Super-Heroes comics, Colossal Boy fell in love with a shapeshifter who had been duped into taking the form of a woman he had been attracted to. The revelation of this made him realize that he had fallen in love with the shapeshifter herself and not with the woman he had thought her to be. Similarly, the Human Torch fell in love with a Skrull imposter; although in the Marvel Universe they eventually broke up, in the MC2 alternate universe, they remarried, are now members of the Fantastic Five, and have a son.

Ill-advised wishes

Many fairy-tale characters have expressed inadvised wishes to have any child at all, even one that has another form, and had such children born to them.[30] At the end of the fairy tale, normally after marriage, such children metamorphize into human form.

"Hans My Hedgehog" was born when his father wished for a child, even a hedgehog. Even stranger forms are possible: Giambattista Basile included in his Pentamerone the tale of a girl born as a sprig of myrtle, and Italo Calvino, in his Italian Folktales, a girl born as an apple.

Sometimes, the parent who wishes for a child is told how to gain one, but does not obey the directions perfectly, resulting in the transformed birth. In Prince Lindworm, the woman eats two onions, but does not peel one, resulting in her first child being a lindworm. In Tatterhood, a woman magically produces two flowers, but disobeys the directions to eat only the beautiful one, resulting her having a beautiful and sweet daughter, but only after a disgusting and hideous one.

Less commonly, ill-advised wishes can transform a person after birth. The Seven Ravens are transformed when their father thinks his sons are playing instead of fetching water to christen their newborn and sickly sister, and curses them.[31] In Puddocky, when three princes start to quarrel over the beautiful heroine, a witch curses her because of the noise.

Monstrous bride/bridegroom

Such wished-for children may become monstrous brides or bridegrooms. Other such characters have no explanation for their forms, because their tales focus on the person who must marry them.

These tales often lean heavily on the promise of the father that his child should marry, or on the financial advantages to her family that she should do so -- factors clearly present in arranged marriages. These tales have often been intrepreted as symbolically representing arranged marriages; the bride's (in particular) revulsion to marrying a stranger being symbolized by his bestial form.[32]

These tales form, broadly, three subclasses.

The heroine must fall in love with the transformed groom. Beauty and the Beast falls under this. This has been interpreted as a young woman's coming-of-age, in which she changes from being repulsed by sexual activity and regarding a husband therefore bestial, to a mature woman who can marry. [33]

The hero or heroine must marry, as promised, and the monstrous form is removed by the wedding. Sir Gawain thus transformed the Loathly lady; although he was told that this was half-way, she could at his choice be beautiful by day and hideous by night, or vice versa, he told her that he would chose what she preferred, which broke the spell entirely.[34] In Tatterhood, Tatterhood is transformed by her asking her bridegroom why he didn't ask her why she rode a goat, why she carried a spoon, and why she was so ugly, and when he asked her, denying it and therefore transforming her goat into a horse, her spoon into a fan, and herself into a beauty. Puddocky is transformed when her prince, after she had helped him with two other tasks, tells him that his father has sent him for a bride. A similar effect is found in Child ballad 34, Kemp Owyne, where the hero can transform a dragon back into a maiden by kissing her three times.[35]

Sometimes the bridegroom removes his animal skin for the wedding night, whereupon it can be burned. Hans My Hedgehog, The Donkey and The Pig King fall under this grouping. At an extreme, in Prince Lindworm, the bride who avoids being eaten by the lindworm bridegroom arrives at her wedding wearing every gown she owns, and she tells the bridegroom she will remove one of hers if he removes one of his; only when her last gown comes off has he removed his last skin, and become a white shape that she can form into a man.[36]

The lindworm's bride was the last of a number of brides. Some other tales using this theme also have one or two who fail the task of the marriage.

In other tales, such as The Brown Bear of Norway, The Golden Crab, The Enchanted Snake and some variants of The Frog Princess, burning the skin is a catastrophe, putting the transformed bride or bridegroom in danger; this is an example of the third grouping.

In the third grouping, the hero or heroine must obey a prohibition; the bride must spend a period of time not seeing the transformed groom in human shape (as in East of the Sun and West of the Moon), or the bridegroom must not burn the animals skins. In these tales, the prohibition is broken, invariably. The hero or heroine must therefore find his bride, or her bridegroom again.[37]

This motif is found in modern fiction mostly in the form of fairytale fantasy. Robin McKinley retold Beauty and the Beast twice, in Beauty and Rose Daughter.

Death

Ghosts sometimes appear in animal form. In The Famous Flower of Serving-Men, the heroine's murdered husband appears to the king as a white dove, lamenting her fate over his own grave. In The White and the Black Bride and The Three Little Men in the Wood, the murdered — drowned — true bride reappears as a white duck. In The Rose Tree and The Juniper Tree, the murdered children become birds who avenge their own deaths.

In some fairy tales, the character can reveal himself in every new form, and so a usurper repeatedly kills the victim in every new form, as in Beauty and Pock Face, A String of Pearls Twined with Golden Flowers, and The Boys with the Golden Stars. This eventually leads to a form into which the character (or characters) can reveal the truth to someone able to stop the villain.

Similarly, the transformation back may be acts that would be fatal. In The Wounded Lion, the prescription for turning the lion back into a prince was to kill him, chop him to pieces, burn the pieces, and throw the ash into water. Less drastic but no less apparently fatal, the fox in The Golden Bird, the foals in The Seven Foals, and the cats in Lord Peter and The White Cat tell the heroes of those stories to cut off their heads; this restores them to human shape.[38]

Shapeshifting in folklore

Popular shapeshifting creatures in folklore are werewolves and vampires (mostly of European, Canadian, and Native American/early American origin), the fox spirits East Asia (including the Japanese kitsune), and the gods, goddesses, and demons of numerous mythologies, such as the Norse Loki or the Greek Proteus. It was also common for deities to transform mortals into animals and plants.

Although shapeshifting to the form of a wolf is specifically known as lycanthropy, and such creatures who undergo such change are called lycanthropes, those terms have also been used to describe any human-animal transformations and the creatures who undergo them. Therianthropy is the more general term for human-animal shifts, but it is rarely used in that capacity.

Other terms for shapeshifters include metamorph, skin-walker, mimic, and therianthrope. The prefix "were-," coming from the Old English word for "man" (masculine rather than generic), is also used to designate shapeshifters; despite its root, it is used to indicate female shapeshifters as well.

Almost every culture around the world has some type of transformation myth, and almost every commonly found animal (and some not-so-common ones) probably has a shapeshifting myth attached to them. Usually, the animal involved in the transformation is indigenous to or prevalent in the area from which the story derives. While the popular idea of a shapeshifter is of a human being who turns into something else, there are numerous stories about animals that can transform themselves as well.[39]

Greco-Roman

Shapeshifting, transformations and metamorphoses serve a wide variety of purposes in classical mythology.

Examples of shapeshifting in classical literature include many examples in Ovid's Metamorphoses, Circe's transforming of Odysseus' men to pigs in Homer's The Odyssey, and Apuleius's Lucius becoming a donkey in The Golden Ass.

Proteus among the gods was particularly noted for his shape-shifting; both Menelaus and Aristaeus seized him to win information from him, and succeeded only because they held on during his manifold shape changes.

This file may be deleted after Thursday, 13 December 2007.

While the Greek gods could use transformation punitively — as for Arachne, turned to a spider for her pride in her weaving, and Medusa, turned to a monster for having sexual intercourse with Poseidon in Athena's temple — even more frequently, the tales using it are of amorous adventure. Zeus repeatedly transformed himself to approach mortal women, both as a means of gaining access:

or to attempt to conceal his affair from Hera

- Io, as a cloud, and Io herself as a white heifer.

More innocently, Vertumnus transformed himself into an old woman in order to gain entry to Pomona's orchard; there, he persuaded her to marry him.

In other tales, the woman appealed to other gods to protect her from rape, and was transformed (Daphne into laurel, Cornix into a crow). Unlike Zeus and other god's shape-shifting, these women were permanently metamorphosed.

In one tale, Demeter transformed herself into a mare to escape Poseidon, but Poseidon counter-transformed himself into a stallion to pursue her, and succeeded in the rape.

Humans were also transformed, for many reasons.

Tiresias once saw two snakes mating and struck the female with his staff; this transformed him into a woman, and he lived as such for many years. At the end, he saw the snakes again, and this time was careful to hit the male, which restored him to male form.

Caenis, having been raped by Poseidon, demanded of him that she be changed to a man. He agreed, and she became Caeneus, a form he never lost, except, in some versions, upon death.

As a final reward from the gods for their hospitality, Baucis and Philemon were transformed, at their deaths, into a pair of trees.

Pygmalion having fallen in love with a statue he had made, Venus had pity on him and transformed the stone to a living woman.

In some variants of the tale of Narcissus, he is turned into a flower.

After Tereus raped Philomela and cut out her tongue to silence her, she wove her story into a tapestry for her sister, Tereus's wife Procne, and the sisters murdered his son and fed him to his father. When he discovered this, he tried to kill them, but the gods changed them all into birds.

Sometimes metamorphoses transformed objects into humans. In the myths of both Jason and Cadmus, one task set to the hero was to sow dragon's teeth; on being sown, they would metamorphosize into belligerent warriors, and both heroes had to trick them into fighting each other to survive. Deucalion and Pyrrha repopulated the world after a flood by throwing stones behind them; they were transformed into people.

British and Irish

Celtic mythology

Though much of Welsh mythology has been lost, shapeshifting magic features several times in what remains.

Pwyll was transformed by Arawn into Arawn's own shape, and Arawn transformed himself into Pwyll's, so that they could trade places for a year and a day.

Llwyd ap Cil Coed transformed his wife and attendants into mice to attack a crop in revenge; when his wife is captured, he turned himself into three clergymen in succession to try to pay a ransom.

Math and Gwydion transform flowers into a woman named Blodeuwedd, and when she betrays her husband Lleu, who is transformed into an eagle, they transform her again, into an owl - Blodeuwedd.

Gilfaethwy having committed rape, and Gwydion his brother having helped him, they were transformed into animals, for one year each, Gwydion into a stag, sow and wolf, and Gilfaethwy into a hind, boar and she-wolf. Each year, they had a child. Math turned the three young animals into boys.

Gwion, having accidentally taken some of wisdom potion that Ceridwen was brewing for her son, fled her through a succession of changes that she answered with changes of her own, ending with his being eaten, a grain of corn, by her as a hen. She became pregnant, and he was reborn in a new form, as Taliesin.

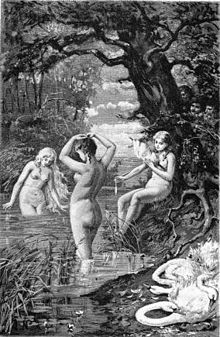

Irish mythology also features shapeshifting. Perhaps the best known myth is that of Aoife who turned her stepchildren, the Children of Lir, into swans to be rid of them. Likewise in the Wooing of Etain Fuamnach jealously turns Étaín into a butterfly.

Sadbh, the wife of the famous hero Fionn mac Cumhaill was changed into a deer by the druid Fer Doirich.

The most dramatic example of shapeshifting in Irish myth is that of Tuan mac Cairill, the only survivor of Partholón's settlement of Ireland. In his centuries long life he became successively a stag, a wild boar, a hawk and finally a salmon prior to being eaten and (as in the Wooing of Étaín) reborn as a human.

British folklore

Fairies, witches, and wizards were all noted for their shapeshifting ability. Not all fairies could shapeshift, and some were limited to changing their size, as with the spriggans, and others to a few forms, such as the each uisge, which appears only as a horse and a young man.[40] Other fairies might have only the appearance of shape-shifting, through their power, called glamour, to create illusions.[41] But others, such as the Hedley Kow, could change to many forms, and both human and supernatural wizards were capable of both such changes, and inflicting them on others.[42]

Witches could turn into hares and in that form steal milk and butter.[43]

Many British fairy tales, such as Jack the Giant Killer and The Black Bull of Norroway, feature shapeshifting.

Norse

Both Odin and Loki are shape-shifters in Norse myth. Unusually, both take on female forms, and Loki in the form of a mare bore Sleipnir. The Lokasenna depicts the two of them taunting each other with it, as having been women through and through, having borne children. (Any myths that depict Odin in female form have been lost, but the Lokasenna does contain references to many myths that are known to be believed.

In the Hyndluljóð, the goddess Freya transformed her protégé Óttar into a boar to conceal him. She also possessed a cloak of robin feathers that allowed her to transform into any kind of bird.

The Volsung saga contains many shapeshifting characters. Siggeir's mother changed to a wolf to help torture his defeated brothers-in-law with slow and igmonious deaths. When one, Sigmund, survived, he and his nephew and son Sinfjötli killed men wearing wolfskins; when they donned the skins themselves, they were cursed to become werewolves.

Fafnir was originally a dwarf or a giant, depending on the exact myth, but in all variants, he became a dragon guarding his hoard.

In more recent folklore, the Nisse is sometimes said to be a shapeshifter. This trait also is attributed to Huldra.

Slavic

In Slavic mythology, werewolves and other human-to-animal shapeshifters are fairly common, usually created as a course of Leszi.

Hinduism

Hindu folklore tells of nāga, snakes that can sometimes assume human form. One nāga took on a man's shape in order to be ordained a monk; the Buddha refused it, but gave it directions on how to ensure it could be reborn as a man after death, in which form it could be ordained.

Far East

Chinese, Japanese, and Korean folklore all tell of animals able to assume human shape. Though they have other traits in common -- such animals are often old, they grow additional tails along with their abilities, and they frequently still have some animal traits to betray them -- there are distinctions between the folklore in the various countries.

Chinese

Chinese folklore contains many tales of animal shapeshifters, capable of taking on human form. The commonest such shapeshifter is the huli jing, a fox spirit which usually appears as a beautiful young woman; most are dangerous, but some feature as the heroines of love stories.

Madame White Snake is one such legend; a snake falls in love with a man, and the story recounts the trials that she and her husband faced.

Japanese

Many Japanese yōkai are animals with the ability to shapeshift. The fox, or kitsune is among the most common, but other such creatures include:

Korean

Korean folklore also contains a fox with the ability to shape-shift. Unlike its Chinese and Japanese counterparts, the kumiho is always malevolent. Usually its form is of a beautiful young woman; one tale recounts a man, a would-be seducer, revealed as a kumiho.[44] She has nine tails and as she desires to be a full human, she uses her beauty to seduce men and eat their hearts (or in some cases livers where the belief is that 100 livers would turn her into a real human).

Tatar

Tatar folklore includes Yuxa, a hundred-year-old snake that can transform itself into a beautiful young woman, and seeks to marry men in order to have children.

Shapeshifting in popular culture

Shapeshifting can be a rich symbolical and narrative tool. Today, the theme appears in many fantasy, science fiction and horror stories; some would even recognize a distinct subgenre of shapeshifting or transformation fiction, with its own genre conventions. Fantasy and science fiction occasionally feature races or species of shapeshifters, and both magic and technology can be used to impose a change in form. Some of the more popular themes include werewolves, vampires, and age regression. In a broader sense, the term includes stories about characters who shrink or grow in size without changing their form.

Transformation in this regard is physical, as opposed to the character development common to many stories, even with no fantastic element, which typically involves characters changing mentally, psychologically or spiritually.

Two episodes of the television show Supernatural (Episode 6, Season 1 "Skin" & Episode 12, Season 2 "Nightshifter") deal with the shapeshifter lore.

Shapeshifting in comics

Calvin created a transmogrification machine that allowed him to transform into anything he wished.

In the Japanese manga Ranma 1/2, by Rumiko Takahashi, many of the main characters are under a curse and shapeshift when are touched by cold water and recover their original form with a little splash of hot water. For example, the hero, Ranma, changes into a beautiful maiden, and his father Genma into a Giant Panda.

In the Japanese manga and anime series Fullmetal Alchemist by Hiromu Arakawa, the Homunculus Envy is able to turn into any person or animal, and occasionally turns his limbs into blades.

The Zoanoids from the Guyver manga and anime series are also notoriously known for their abilities to change from humans into monsters.

In the Japanese manga and anime series Fruits Basket, people who are members of The Zodiac transform into their respective zodiac animals when hugged. Over time, they gain the ability to change back into their human forms.

Psychology of transformation fiction

Science fictional transformation fiction tends to feed a sense of discovery and suggest the unlocking of potential. This may be an analogy for the idealization of the experience of a teenager who discovers that puberty has changed his body, including increased strength and physical ability. Jack L. Chalker's Wellworld series is an example of this sort. The eponymous planet is populated by hundreds of different species, each in its own territory, and visitors become residents by being forcibly transformed at the polar immigration entry points into a member of a randomly selected resident species.

Fantasy transformation fiction is often mystical or dynamic, focusing on the change of the person's identity when transformed. This may be an analogy for learning to take a different perspective. Patricia A. McKillip's Riddlemaster of Hed series includes transformations of wizards into mountain sheep, ancient trees, ravens, and even the wind; each change leaves its mark on the essence of the wizard who transforms. In T.H. White's The Sword in the Stone, the wizard Merlyn transforms young Arthur into a variety of animals so he can learn from the animals the lessons he will need to be a good king.

Horror transformation fiction captures a feeling of fear, of people suddenly becoming monsters, of yourself becoming a monster, of things prowling in the night that used to be human. This is possibly an analogy for emotions that are so strong, they rip away one's rationality and leave one a beast. An American Werewolf in London is a perfect example; a young man is bitten, and without his permission or desire, becomes a creature of darkness that exists to kill.

Transformation can also be viewed as a metaphor for puberty and budding sexuality, such as in the Disney film The Shaggy Dog. In the story, the teenage protagonist Wilby Daniels finds himself under the curse of a ring reputed to having belonged to Lucrezia Borgia that causes him to randomly transform into a sheepdog. This happens concurrently with the arrival of a beautiful and exotic neighbor that Wilby has a crush on; throughout the film he finds himself helplessly transforming into a dog, frequently in her presence. Most tellingly, this happens at a dance where he is slow-dancing with her — an activity that might cause the average adolescent male to find himself getting an erection; though this gets filtered into him growing shaggy hair and becoming a beast, essentially his animal instincts take control of him and he rushes away from the social activity humiliated.

In some stories, an unexpected but welcome transformation (especially various forms of lycanthropy) plays a thematic role similar to the plot device of the protagonist being a commoner who finds out they are actually royal, or have unsuspected magical talent, or have some other wonderful unsuspected destiny. In others, a transformation imposed from without by a hostile entity is a challenge to be overcome; the protagonist seeks a way to reverse the transformation and regain their original form. In many such stories, the final resolution involves the unwillingly transformed protagonist coming to terms with their new shape and turning it to their advantage rather than finding a way to return to "normal".

Shapeshifting in real life

Some animals, particularly octopi, are able to change their body shape and color to mimic other creatures and objects, for camouflage or to hide in narrow spaces. The Mimic Octopus is noted for its ability to impersonate sea snakes, widely different fish species, and rock formations.

Insects often undergo metamorphosis, in a transformation between their larval and adult stages. While fictional metamorphoses are almost always permanent, these changes are always so.

Transformation enthusiasts

Many children have animal transformation fantasies and shapeshifting is a well-known feature of fairy tales, such as the story of the Frog Prince and The Spiderwick Chronicles . Interest in transformation isn't limited just to them, though; the concept captures some imaginations of all ages. The subject is rather obscure and there's no established term for those who like transformations; the general expression is just "TF fans". Note that having an interest in shapeshifting is distinct from belonging to therians, otherkin or any other group that actually identifies with or wishes to become something else.

It is possible for this interest to be sexually charged, or to accentuate other fetishes; for instance, forced shapeshifting can lend itself well to themes of dominance. The result is a transformation fetish.

Websites and online communities about transformation exist, both clean and otherwise, although for someone who e.g. just likes coming across shapechanges on TV, a site dedicated for appreciating them might be entirely too much. The Transformation Story Archive is a prominent example of its kind.

Two currently prominent webcomics feature transformations for their own sake: El Goonish Shive is technology- and magic-based and more character-driven, while The Wotch is somewhat younger, magic-based and considerably more madcap.

See also

- List of shapeshifters in myth and fiction

- Resizing (in fiction)

- Self reconfigurable

- Werewolves in fiction

- Animal transformation fantasy

- Shapeshifting as a comic book superpower

- Soul eater (folklore)

Notes and references

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Shapeshifting", p 858 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Metamorphosis", p 641 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Transformation", p 960 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ Marina Warner, From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales And Their Tellers, p 353 ISBN 0-374-15901-7

- ^ Anne Wilson, Traditional Romance and Tale, p 84, D.S. Brewer, Rowman & Littlefield, Ipswitch, 1976, ISBN 0-87471-905-4

- ^ David Colbert, The Magical Worlds of Harry Potter, p 28-9, ISBN 0-9708442-0-4

- ^ Jack Zipes, When Dreams Came True: Classical Fairy Tales and Their Tradition, p 176-7 ISBN 0-415-92151-1

- ^ Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation; Napier, Susan Jolliffe; ISBN-13: 9780312238636

- ^ Animerica Vol.1, #2; http://www.furinkan.com/takahashi/takahashi7.html

- ^ Francis James Child, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, v 1, p 313-4, Dover Publications, New York 1965

- ^ Maria Tatar, p 193, The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- ^ Stephen Prickett, Victorian Fantasy p 86 ISBN 0-253-17461-9

- ^ Erik J. Wielenberg, "Aslan the Terrible" p 226-7 Gregory Bassham ed. and Jerry L. Walls, ed. The Chronicles of Narnia and Philosophy ISBN 0-8126-9588-7

- ^ James F. Sennett, "Worthy of a Better God" p 243 Gregory Bassham ed. and Jerry L. Walls, ed. The Chronicles of Narnia and Philosophy ISBN 0-8126-9588-7

- ^ Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p 57, ISBN 0-292-78376-0

- ^ Richard M. Dorson, "Foreword", p xxiv, Georgias A. Megas, Folktales of Greece, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1970

- ^ Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p 57, ISBN 0-292-78376-0

- ^ Stith Thompson, The Folktale, p 56, University of California Press, Berkeley Los Angeles London, 1977

- ^ Stith Thompson, The Folktale, p 89, University of California Press, Berkeley Los Angeles London, 1977

- ^ David Colbert, The Magical Worlds of Harry Potter, p 23, ISBN 0-9708442-0-4

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Transformation", p 960 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ Francis James Child, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, v 1, p 336-7, Dover Publications, New York 1965

- ^ L. Sprague de Camp, Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy, p 266 ISBN 0-87054-076-9

- ^ Stith Thompson, The Folktale, p 55-6, University of California Press, Berkeley Los Angeles London, 1977

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Shapeshifting", p 858 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Shapeshifting", p 858 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Transformation", p 960 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ Maria Tatar, The Annotated Brothers Grimm, p 226 W. W. Norton & company, London, New York, 2004 ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ Joseph Jacobs, English Fairy Tales, "The Laidly Worm of Spindleston Heugh"

- ^ Maria Tatar, Off with Their Heads! p. 60 ISBN 0-691-06943-3

- ^ Maria Tatar, The Annotated Brothers Grimm, p 136 ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ Maria Tatar, Off with Their Heads! p. 140-1 ISBN 0-691-06943-3

- ^ Steven Swann Jones, The Fairy Tale: The Magic Mirror of Imagination, Twayne Publishers, New York, 1995, ISBN 0-8057-0950-9, p84

- ^ Anne Wilson, Traditional Romance and Tale, p 89, D.S. Brewer, Rowman & Littlefield, Ipswitch, 1976, ISBN 0-87471-905-4

- ^ Francis James Child, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, v 1, p 306, Dover Publications, New York 1965

- ^ Terri Windling, "Married to Magic: Animal Brides and Bridegrooms in Folklore and Fantasy"

- ^ Terri Windling, "Married to Magic: Animal Brides and Bridegrooms in Folklore and Fantasy"

- ^ Maria Tatar, The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Fairy Tales, p174-5, ISBN 0-691-06722-8

- ^ Terri Windling, "Married to Magic: Animal Brides and Bridegrooms in Folklore and Fantasy"

- ^ Katharine Briggs, An Encyclopedia of Fairies, Hobgoblins, Brownies, Boogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures, "Shape-shifting", p360. ISBN 0-394-73467-X

- ^ Katharine Briggs, An Encyclopedia of Fairies, Hobgoblins, Brownies, Boogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures, "Glamour", p191. ISBN 0-394-73467-X

- ^ Katharine Briggs, An Encyclopedia of Fairies, Hobgoblins, Brownies, Boogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures, "Shape-shifting", p360. ISBN 0-394-73467-X

- ^ Eddie Lenihan and Carolyn Eve Green, Meeting The Other Crowd: The Fairy Stories of Hidden Ireland, p 80 ISBN 1-58542-206-1

- ^ Heinz Insu Fenkl, "A Fox Woman Tale of Korea"

- Hall, Jamie, Half Human, Half Animal: Tales of Werewolves and Related Creatures (AuthorHouse, 2003 ISBN 1-4107-5809-5)

External links

- The Transformation Stories List (not updated recently)

- Transformation Stories Archive (not updated recently)

- Transformation Stories, Art, Talk (online magazine)

- TFCentral - A portal dedicated to transformation. Hosting, forums, image gallery, story archives, and chat.

- Portal of Transformation - Site with sections on the folklore behind a number of different shapeshifters from around the world.

- Stories set in fictional town "Barken, TX"

- The Siren Song - Started back in 1997 - this site is home to original TG transformation/shapeshifting art, comics and animated shorts.

- Shapeshifters in Love - A series of articles about shapeshifting characters in romance and speculative fiction.