River Wear

| River Wear | |

|---|---|

| |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Mouth | Sunderland |

| Length | 96 km (60 miles) |

The River Wear (Template:PronEng) is a river in North East England. Rising in the east Pennines, its head waters consisting of several streams draining from the hills between Killhope Law and Burnhope Seat, the head of the river is held to be in Wearhead, County Durham at the confluence of Burnhope Burn and Killhope Burn. This is shown on Ordnance Survey maps, and on the County Durham GIS online. However, a map produced by Durham County Council, and used on an interpretation board at Cowshill shows the River Wear extending from Wearhead to Killhope. Excepting that this apparent extension of the Wear is an error, it can be assumed that there are attempts to reclassify Killhope Burn as the River Wear. This would make sense, as it would then give the River Wear a source.

The river flows eastwards through Weardale, one of the larger valleys of west County Durham, subsequently turning south-east, and then north-east, meandering its way through the Wear Valley and County Durham to the North Sea where it outfalls at Wearmouth on Wearside in Sunderland. The river is 96 km (60 miles) from head to mouth. Prior to the creation of Tyne and Wear, the Wear had been the longest river in England with a course entirely within one county. The Weardale Way, a long-distance public footpath, roughly follows the entire route, including the length of Killhope Burn.

Geology and History

The Wear rises in the east Pennines, an upland area raised up during the Caledonian orogeny. Specifically, the Weardale Granite underlies the headwaters of the Wear. Devonian Old Red Sandstone in age, the Weardale Granite does not outcrop, and was initially surmised, and subsequently proved as a result of the famous Rookhope borehole. It is the presence of this granite that has both retained the upland nature of this area (less through its relative hardness, and more due to isostatic equilibrium), and accounts for heavy local mineralisation, although it is considered that most of the mineralisation occurred during the Carboniferous period. Mining of lead ore has been known in the area of the headwaters of the Wear since Roman times, and continued into the nineteenth century when it accounts for the early extension of the then-new railways westwards along the Wear valley. Fluorspar, another mineral associated with the intrusion of the Weardale Granite, became important in the nineteenth century manufacture of steel. Along with overlying Carboniferous Limestone and Carboniferous Coal Measures, both important raw materials for iron and steel manufacture, as well as Carboniferous sandstone, useful as a refractory material, the local presence of fluorspar explains why iron and steel manufacture flourished in the Wear valley during the nineteenth century, ironstone (although having been sought by miners in Weardale) being imported from south of the Tees. Spoil heaps from the abandoned lead mines can still be seen, and since the last quarter of the twentieth century have been the focus of attention for the recovery of gangue minerals, such as fluorspar for the smelting of aluminium. However, abandoned mines and their spoil heaps continue to contribute to the mineral pollution of the river and its tributaries. This has significance because the River Wear is an important source of drinking water for many of the inhabitants along its course. The former cement works at Eastgate, until recently run by Steetley, was based on an inlier of limestone.

The upland area of Upper Weardale retains a flora that relates, almost uniquely in England, to the end of the last Ice Age. This may, in part, be due to the Pennine areas of Upper Weardale and Upper Teesdale being the site of the shrinking ice cap. The glaciation left behind many indications of its presence, including lateral moraines and material from the Lake District and Northumberland, although surprisingly few drumlins. After the Ice Age, the Wear valley became thickly forested. During the Neolithic period and increasingly in the Bronze Age, the forests were progressively cleared for agriculture.

It is thought that the course of the River Wear, prior to the last Ice Age, was much as it is now as far as Chester-le-Street. This can be established as a result of boreholes, of which there have been many in the Wear valley due to coal mining. However, northwards from Chester-le-Street, the Wear may have originally followed the current route of the lower River Team. The confluence of the ancient River Wear with the River Tyne is thought to have been at Dunston, two miles downstream from the Tyne's confluence with the River Derwent. Augmented with flow from the ancient River Wear, and with substantially lower sea levels, the River Tyne had gouged a deep river valley as it flowed towards the North Sea between what are now Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead, Hebburn, Wallsend and Jarrow, to the coast at Tynemouth and South Shields. The last glaciation reached its peak about 18,500 years ago, from which time it also began a progressive retreat, leaving a wide variety of glacial deposits in its wake, filling existing river valleys with silt, sand and other glacial till. At about 14,000 years ago, retreat of the ice paused for maybe 500 years at the city of Durham. This can be established by the types of glacial deposits in the vicinity of Durham City. The confluence of the River Browney was pushed from Gilesgate (the abandoned river valley still exists in Pelaw Woods), several miles south to Sunderland Bridge (Croxdale). At Chester-le-Street, when glacial boulder clay was deposited blocking its northerly course, the River Wear was diverted eastwards towards Sunderland where it was forced to cut a new, shallower valley. The gorge cut by the river through the Permian magnesian limestone can be seen most clearly at Ford Quarry. Whereas the lower reaches of the River Tyne had cut deeply into the underlying bedrock, therefore subsequently allowing the Tyne to be dredged, thus permitting deep draught shipping, the bedrock beneath the Wear at Sunderland was too shallow to permit deep draught shipping. This may go some way to explain the greater industrial growth of Tyneside compared to Wearside.

In the 17th edition of Encycloaedia Britannica (1990), reference is made to a pre-Ice Age course of the River Wear outfalling at Hartlepool.

Much of the River Wear is associated with the history of the Industrial Revolution. Its upper end runs through lead mining country, until this gives way to coal seams of the Durham coalfield for the rest of its length. As a result of lead and coal mining, the Wear valley was amongst the first places to see the development of railways. The Weardale Railway continues to run occasional services between Stanhope and Wolsingham.

Course

Wearhead to Bishop Auckland

There are several towns, sights and tourist places along the length of the river. The market town of Stanhope is known in part for the ford across the river. From here the river is followed by the line of the Weardale Railway, which crosses the river several times, through Frosterley, Wolsingham, and Witton-le-Wear to Bishop Auckland.

Bishop Auckland to Durham

On the edge of Bishop Auckland the Wear passes below Auckland Park and Auckland Castle, the official residence of the Bishop of Durham and its Deer Park. A mile or so downstream from here, the Wear passes Binchester Roman Fort, Vinovia, having been crossed by Dere Street, the Roman road running from Eboracum (now York} to Coria (now Corbridge) close to Hadrian's Wall. From Bishop Auckland the River Wear meanders in a general northeasterly direction, demonstrating many fluvial features of a mature river, including wide valley walls, fertile flood plains and ox-bow lakes. Bridges over the river become more substantial, such as those at Sunderland Bridge (near Croxdale), and Shincliffe. At Sunderland Bridge the River Browney joins the River Wear.

Durham

When it reaches the city of Durham the River Wear passes through a deep, wooded gorge, from which several springs emerge, historically used as sources of potable water; and a number of coal seams are visible. Twisting sinuously in an incised meander, the river has cut deeply into the (Cathedral Sandstone) bedrock, creating a peninsula which is known as such in Durham. This peninsula was formerly exploited as a defensive enclosure, and include a motte, inner bailey and outer bailey, now represented by road alignments, city walls and the imposing Norman monuments of Durham Castle and Durham Cathedral, The latter contains the tomb and pilgrimage shrine of St. Cuthbert and the tomb of St. Bede. Between the castle and cathedral is an open lawned space named Palace Green. Palace Green and its encircling buildings is a UN World Heritage Site. As the Wear flows though the city of Durham, it passes beneath eight bridges: Bath's Bridge (modern footbridge); New Elvet Bridge (modern road bridge); Elvet Bridge (medieval road bridge, now largely pedestianised); Kingsgate Bridge (modern footbridge); Prebends' Bridge (18th century road bridge, now effectively pedestriansed); Framwellgate Bridge (medieval road bridge, now largely pedestianised); Milburngate Bridge (modern road bridge); Pennyfeather Bridge (modern footbridge). Beneath Elvet Bridge are Brown's Boats (rowing boats for hire) and the mooring for the Prince Bishop, a pleasure cruiser. Photographs of these bridges are shown in the Gallery below. The River Wear at Durham was featured on a television programme Seven Natural Wonders as one of the wonders of the North.

There are two weirs impeding the flow of the river through the city: the first at the Old Fulling Mill, the second, more complex weir, beneath Milburngate Bridge and beside the former ice rink, includes a salmon leap and fish counter (largely trout and salmon), and is on the site of a former ford. Considering that 138,000 fish have been counted migrating upriver since 1994, it may not be surprising that a family of cormorants live on this weir, and can frequently be watched stretching their wings in an attempt to cool off after feeding.

The river's Elvet Banks also lend their name to a tune in the LCMS 2006 hymnbook, used (appropriately) for a hymn for baptism.

Durham to Chester-le-Street

Between Durham City and Chester-le-Street, ten miles due north, the River Wear changes direction repeatedly, flowing south westwards several miles downstream having passed the medieval site of Finchale Priory, a former chapel and later a satellite monastery depending on the abbey church of Durham Cathedral. Two miles downstream, the river is flowing south eastwards. The only road bridge over the Wear between Durham and Chester-le-Street is Cocken Bridge. As it passes Chester-le-Street, where the river is overlooked by Lumley Castle, its flood plain has been developed into The Riverside, the home pitch of Durham County Cricket Club. Passing through the Lambton Estate (still owned by the Lambton family, and briefly a lion park during the 1970s) the river becomes tidal, and therefore navigable.

Chester-le-Street to Sunderland

On exiting the Lambton estate the river leaves County Durham and enters the City of Sunderland, specifically the southern/south-eastern edge of the new town of Washington. At Fatfield the river passes beneath Worm Hill, around which the Lambton Worm is reputed to have curled its tail.[1]

Already the riverbanks are showing evidence of past industrialisation, with former collieries and chemical works. A little further downstream the river passes beneath the Victoria Viaduct. Named after the newly-crowned queen, the railway viaduct opened in 1838, was the crowning achievement of the Leamside Line, then carrying the East Coast Main Line. A mile to the east is Penshaw Monument, a local iconic landmark. As the river leaves the environs of Washington, it forms the eastern boundary of Washington Wildfowl Trust.

Sunderland

Shadows in Another Light, a sculpture in which the shadow cast by a tree represents a hammerhead crane, unique to the Sunderland shipyards,[2] can be seen at the left of this image.

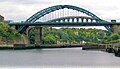

Having flowed beneath the A19 trunk road, the river enters the suburbs of Sunderland. The riverbanks show further evidence of past industrialisation, with former collieries, engineering works and dozens of shipyards. In their time, Wearside shipbuilders were some of the most famous and productive shipyards in the world. The artist L. S. Lowry visited Sunderland repeatedly and painted pictures of the industrial landscape around the river. Three bridges cross the Wear in Sunderland: the Queen Alexandra Bridge to the west, and the Wearmouth rail and road bridges in the city centre.

On both banks at this point there are modern developments, some belonging to the University of Sunderland (St. Peter's Campus; Scotia Quay residences) and to the National Glass Centre. A riverside sculpture trail runs alongside this final section of its north bank.[3] The St Peter's Riverside Sculpture Project was created by Colin Wilbourn, with crime novelist and ex-poet Chaz Brenchley. They worked closely with community groups, residents and schools.[4]

As the river approaches the sea, the north bank (Roker) has a substantial residential development and marina. A dolphin nick-named Freddie was a frequent visitor to the marina, attracting much local publicity. However, concern was expressed that acclimatising the dolphin to human presence might put at risk the safety of the dolphin regarding the propellors of marine craft. The south bank of the river is occupied by what remains of the Port of Sunderland, once thriving and now almost gone.

The River Wear flows out of Sunderland between Roker Pier and South Pier, and into the North Sea.

Crossings

- Wearhead Bridge (road)

- Daddry Shield brige (road)

This list is incomplete; you can help by adding missing items. |

- Frosterley Bridge (road, connects Weardale with Eggleston and Middleton-in Teesdale)

- Witton-le-Wear

- Bishop Auckland Railway Viaduct, (road)

- Bishop Skirlaw Bridge, (road)

- Page Bank Bridge, (road, connects Spennymoor to Willington)

- Croxdale Viaduct, (rail)

- Sunderland Bridge, (former route of road)

- Croxdale Bridge, A167 (road)

- Shincliffe Bridge, A177 (road) (old print of bridge at Shincliffe)

- Maiden Castle Bridge (foot)

- Bath's Bridge (foot)

- New Elvet Bridge (road)

- Elvet Bridge (road, pedestrianised)

- Kingsgate Bridge (foot)

- Prebends Bridge (road, pedestrianised)

- Framwellgate Bridge (road, pedestrianised)

- Milburngate Bridge (road, foot)

- Pennyfeather Bridge (foot)

- viaduct at Raintonpark woods (railway, disused)

- Finchale Priory / Cocken Woods Bridge (foot)

- Cocken Bridge (road)

- Lumley Bridge (road)

- A1(M) bridge (road)

- Lambton Bridge, Chester Road A183 (road)

- Chester New Bridge (road)

- Lamb Bridge, Lambton Castle (private)

- New Bridge, Lambton Castle (private)

- Chartershaugh Bridge, Washington Highway (A182) (road)

- Fatfield Bridge (road)

- Victoria Viaduct (railway, disused)

- Washington Cox Green (foot)

- A19 Viaduct (road)

- Queen Alexandra Bridge (road)

- Wearmouth Rail Bridge (rail/Tyne and Wear Metro)

- Wearmouth Bridge (road, foot)

See also

References

- ^ "The Lambton Worm". The Legends and Myths of Britain. Retrieved 2007-06-17.

- ^ "Alice in Sunderland". chazbrenchley.co.uk. Retrieved 2007-06-17.

- ^ "St Peter's Riverside Sculpture Project". chazbrenchley.co.uk. Retrieved 2007-06-17.

- ^ Talbot, Bryan (2007). Alice in Sunderland: An Entertainment. London: Jonathon Cape. pp. 95–107. ISBN 0-224-08076-8.

Sources Consulted

Natural Environment Research Council, Institute of Geological Sciences, 1971, "British Regional Geology: Northern England" Fourth Edition, HMSO, London.

Johnson, G.A.L. & Hickling, G. (eds.), 1972, "Geology of Durham County", Transactions of the Natural History Society of Northumberland, Durham and Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Vol.41, No.1.

'Wear River', "Encyclopaedia Britannica", 17th Edition, 1990.

Gallery

-

Croxdale Viaduct carries the East Coast Main Line railway between London and Edinburgh over the River Wear at Sunderland Bridge, near Durham City

-

Sunderland Bridge over the River Wear near Durham City. The brown colouration of the water is due to moorland peat that has been washed into the river upstream during heavy rainfall.

-

Maiden Castle footbridge links the University of Durham's sports centre with its football and rugby pitches across the river. Running over the footbridge at a certain speed creates a resonance such that the bridge vibrates.

-

Baths Bridge is a footbridge named after the swimming baths at the southern end of the bridge. In warm summer weather, youths eschew the chlorinated water of the swimming pool, and throw themselves into the river from the centre of Baths Bridge, a feat that requires courage as the river is shallow.

-

New Elvet Bridge over the River Wear in Durham City

-

Elvet Bridge over the River Wear in Durham City. Elvet Bridge is now largely pedestrianised.

-

Prebends Bridge over the River Wear in Durham City. Although built as a road bridge, subsidence due to coal mining beneath the bridge means that Prebends Bridge is almost exclusively pedestrianised.

-

Prebends Bridge over the River Wear in Durham City.

-

Milburngate Bridge (foreground) and Framwellgate Bridge (background) are respectively modern and ancient. The series of weirs is on the site of an ancient ford, whereas a modern fish-counter on one of the weirs allows the National Rivers Authority to count the fish (mostly trout and salmon) migrating upstream.

-

Pennyfeather Bridge is a millennium footbridge over the River Wear in Durham City.

-

Cocken Bridge over the River Wear is the only road crossing between Durham and Chester-le-Street. It is a narrow bridge on a twisty, narrow road, but serves as a rat-run between the A690 at West Rainton and the A167 between Pity Me (Durham City) and Chester-le-Street, by-passing Durham city centre.

-

Fatfield Bridge over the River Wear, in Fatfield, beside Worm Hill, and close to Penshaw Monument.

-

Victoria Viaduct over the River Wear near Washington. This massive railway viaduct, a spectacular engineering feat on the Leamside Line, was completed in 1839, and carried the East Coast Main Line between London and Edinburgh until 1872.

-

Hylton Viaduct carries the A19 over the River Wear. North and South Hylton are respectively on the north and south banks of the river; Washington lies upstream and Sunderland downstream. Many years ago, a ferry plied the river close by, and the name of the road from which this photograph was taken is called Ferryboat Lane. Washington's Nissan car factory is just beyond the viaduct, built on the site of the former Sunderland Airport.