Benjamin Banneker

This article needs attention from an expert in History. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. (June 2007) |

Benjamin Banneker, originally Banna Ka, or Bannakay (November 9, 1731–October 9, 1806) was a free African American astronomer, mathematician, surveyor and almanac author.

Family history

Banneker's mother was Mary Bannaky (1710-1790–?). Oral tradition states that his grandmother was a European American named Molly Welsh. The story goes that Molly became the owner of a farm and married one of her slaves named Bannakay, whom she freed. They had four girls and Mary was the oldest.

Benjamin's father, Robert Banna Ka, was a former slave who had built a series of dams and watercourses that successfully irrigated the family farm at Ellicott's Mills, where Benjamin was born and lived most of his life. Benjamin was taught to read and do simple arithmetic by his grandmother and by a Quaker schoolmaster, who changed his name to Banneker. (During Banneker's lifetime, Quakers were leaders in the antislavery movement and advocates of racial equality in accordance with their Testimony of Equality belief.) Once he was old enough to help on his parents' farm, Benjamin's formal education ended.

Clockmaking

Apparently using a pocketwatch as a model, Banneker carved large-scale wooden replicas of each piece and used the parts to make a wooden clock. The clock continued to work for many years.

Astronomy and geographical survey work

Banneker began his self-taught study of astronomy at age 58. In early 1791, the Quaker Andrew Ellicott hired Banneker to assist in a survey of the boundaries of the 100 square-mile district (the future District of Columbia) that Maryland and Virginia had ceded to the federal government following passage of the federal Residence Act.

Banneker's duties on the survey team consisted primarily of making astronomical observations to ascertain distances and locations along the district's boundaries and of maintaining a clock that he used when relating points along the boundaries to the positions of stars at specific times. Because of illness and the difficulties in helping to survey at the age of 59 an extensive area that was largely wilderness, Banneker left the boundary survey in April 1791 and returned to his home at Ellicott's Mills to work on an ephemeris.[1]

At Ellicott's Mills, Banneker made astronomical calculations that predicted solar and lunar eclipses for inclusion in his ephemeris. He placed the ephemeris in Benjamin Banneker's Almanac, which an anti-slavery society published from 1792 through 1797. He also kept a series of astronomical journals that contained his notebooks for astronomical observations, his diary, and his mathematics notebook.[2]

Views on slavery and racial equality

After departing the federal capital area, Banneker expressed a vision of social justice and equity that he wished to be adhered to in the everyday fabric of American life. He wrote to the Secretary of State and author of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson, a plea for justice for African Americans, calling on the colonists' personal experience as "slaves" of Britain and quoting Jefferson's own words. To support his plea, Banneker included a copy of his newly published ephemeris with its astronomical calculations. Jefferson replied to Banneker less than two weeks later in a series of statements asserting his own interest in the advancement of the equality of America's black population. Jefferson also forwarded a copy of Banneker's Almanac to the French Academy of Sciences in Paris. It was also used in Britain's House of Commons. Benjamin died on October 9 1806 at age 74 in his log cabin. He never married.

Following a life journey that would be echoed by others after him including Martin Luther King Jr., and, being largely supported by European Americans who promoted racial equality and an end to racial discrimination, Banneker spent the early years of his advocacy efforts arguing specifically for the rights of American Blacks, but turned in his later years to an argument for the peaceful equality of all mankind. In 1792, Banneker included in his Almanac a plan for the creation of a new Department in the American federal government. Several pages of the Almanac outlined a Department of Peace, testifying to his ethical positions and to the need to balance a Department of War with a Department of Peace dedicated to promoting the de-escalation of national and international conflict.

Letter to Thomas Jefferson on racism

"Sir, how pitiable is it to reflect, that although you were so fully convinced of the benevolence of the Father of Mankind, and of his equal and impartial distribution of these rights and privileges, which he hath conferred upon them, that you should at the same time counteract his mercies, in detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my brethren, under groaning captivity and cruel oppression, that you should at the same time be found guilty of that most criminal act, which you professedly detested in others, with respect to yourselves."[3]

Mythology of Benjamin Banneker

A substantial mythology exaggerating Banneker's accomplishments has developed during the two centuries that have elapsed since he lived. One such urban legend describes Banneker's alleged activities after he left the federal district boundary survey.

While Andrew Ellicott and his team were conducting the district boundary survey, Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant was making a plan for the federal capital city (the City of Washington), which would be located in a relatively small area northeast of the Potomac River at the center of the much larger 100 square mile federal district. In 1792, President George Washington accepted the resignation of L'Enfant, who had decided to quit out of frustration with his superiors after completing his plan for the federal city.

According to the Banneker legend, L'Enfant took his plans with him after he resigned, leaving no copies behind. As the story is told, Banneker spent two days reconstructing the bulk of the city's plan from his presumably photographic memory. The plans that Banneker puportedly drew from memory provided the basis for the later construction of the federal capital city.

In one version of the legend, Banneker and Andrew Ellicott both surveyed the area of, and configured the final layout for, the placement of major governmental buildings, boulevards and avenues while reconstructing L'Enfant's plan. According to this version, Banneker's astronomical calculations and implementations established points of astronomical significance in the capital city, including those of the 16th Street Meridian, the White House, the Capitol and the Treasury Building.[4]

However, the legend cannot be correct. Banneker left the federal capital area and returned to Ellicott's Mills in April 1791. At that time, L'Enfant was still developing his plan for the federal city and had not yet resigned from his job.[5][6] L'Enfant presented his plan to President George Washington in August 1791, four months after Banneker had left.[7]

Further, there was never any need to reconstruct L'Enfant's plan. At the time that L'Enfant resigned, President Washington and perhaps others, including Andrew Ellicott, possessed copies of various versions of the plan that L'Enfant had prepared. After largely completing the boundary survey, Ellicott began a survey of the federal city in accordance with L'Enfant's plan and continued the city survey in accordance with revisions that he alone made after L'Enfant departed.[8] Moreover, the U.S. Library of Congress presently owns a copy of a plan for the federal city that bears the adopted name of the plan's author, "Peter Charles L'Enfant".[9][10]

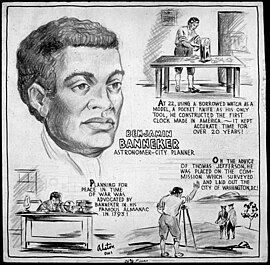

A 1943 cartoon by Charles Alston embellished the Banneker legend by stating that Banneker was a "city planner" and "was placed on the commission which surveyed and laid out the city of Washington, D.C." The cartoon also stated that Banneker "constructed the first clock made in America".[11]

In 1976, the singer-songwriter Stevie Wonder celebrated Banneker's mythological achievements in his song "Black Man", from the album "Songs in the Key of Life". A stanza in the song states: "Who was the man who helped design the nation's capitol, made the first clock to give time in America and wrote the first almanac? Benjamin Banneker - a black man."[12] None of these statements are correct. Banneker did not help design either the U.S. Capitol or the nation's capital city. "Pierce's (Peirse's) Almanac of 1639 calculated for New England and printed by Stephen Day" preceded Banneker's birth by nearly a century.[13] The first known American clock was made in 1680.[14]

In 2008, the District of Columbia government considered selecting an image of Banneker to represent the District on the side of a 2009 commemorative United States quarter dollar coin. Although the District chose to commemorate another person on that coin, the District's mayor, Adrian M.Fenty, sent a letter to the Director of the United States Mint that claimed that Banneker had "played an integral role in the physical design of the nation's capital."[15] In reality, Banneker played no role at all in that design process.

Benjamin Banneker Park and Memorial, Washington, D.C.

A small urban park memorializing Benjamin Banneker is located at a prominent overlook at the south end of L'Enfant Promenade in southwest Washington, D.C., a half mile south of the Smithsonian Institution's "Castle" on the National Mall.[16] Although the National Park Service administers the park, the Government of the District of Columbia owns the park's site, which is inside of a traffic circle (Benjamin Banneker Circle). The park, which was constructed in 1970, is now stop number 8 on Washington's Southwest Heritage Trail.[17] In 2004, the D.C. Preservation League listed the park as one of the most endangered places in the District of Columbia.[18]

The Washington Interdependence Council is planning to construct a monumental memorial to Banneker at or near the site of the park.[19] On November 8, 2006, the Council held a charrette to select the artist that would design the memorial.[20]

Notes

- ^ Boundary markers of the Nation's Capital: a proposal for their preservation & protection : a National Capital Planning Commission Bicentennial report. National Capital Planning Commission, Washington, DC, 1976; for sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office

- ^ Fasanelli, Florence; Jagger, Graham; Lumpkin, Bea, Benjamin Banneker's Trigonometry Puzzle and Mahony, John F., Benjamin Banneker's Inscribed Equilateral Triangle in Convergence in Math DL, The Mathematical Sciences Digital Library in MAA Online: official website of The Mathematical Association of America Accessed August 11, 2008.

- ^ University of Virginia Library

- ^ The ninth and tenth paragraphs of the "His Story" page in official website of the Washington Interdependence Council: Administrators of the Benjamin Banneker Memorial (Accessed August 6, 2008), the fourth paragraph of the section entitled "BENJAMIN BANNEKER (1731-1806)" in Benjamin Banneker page in "ChickenBones: A Journal for Literary & Artistic African-American Themes" website (Accessed August 6, 2008) and the first paragraph of the webpage entitled "Benjamin Banneker (1731-1806)" in official website of the Brookhaven National Laboratory (Accessed August 8, 2008) relate part or all of this urban legend.

- ^ Bedini, Silvio A., The Life of Benjamin Banneker. Scribner, New York, 1971, c1972. ISBN 0-684-12574-9

- ^ Arnebeck, Bob, Through a Fiery Trial: Building Washington, 1790-1800. Madison Books, Lanham. Distributed by National Book Network, c1991. ISBN 0-8191-7832-2

- ^ Stewart, John (1899). "Early Maps and Surveyors of the City of Washington, D.C". Records of the Columbia Historical Society. 2: p. 52.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Bowling, Kenneth R., Creating the federal city, 1774-1800 : Potomac fever. American Institute of Architects Press, Washington, D.C., 1988.

- ^ Library of Congress' copy of L'Enfant's Plan in official website of the U.S. Library of Congress. Accessed August 6, 2008. The Library's webpage describing the plan states: "Selected by Washington to prepare a ground plan for the new city, L'Enfant arrived in Georgetown on March 9, 1791, and submitted his report and plan to the president about August 26, 1791. It is believed that this plan is the one that is preserved in the Library of Congress. After showing L'Enfant's manuscript to Congress, the president retained custody of the original drawing until December 1796, when he transferred it to the City Commissioners of Washington, D.C. One hundred and twenty-two years later, on November 11, 1918, the map was presented to the Library of Congress for safekeeping."

- ^ A copy of the oval in L'Enfant's plan that identifies the plan's author as "Peter Charles L'Enfant" is inscribed several yards west of an inlay of the plan in Freedom Plaza on Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, in downtown Washington, D.C. The coordinates of the inscription are: 38°53′45″N 77°01′53″W / 38.895845°N 77.031286°W

- ^ 1943 Cartoon by Charles Alston: "BENJAMIN BANNEKER - ASTRONOMER-CITY PLANNER". Image available from the Archival Research Catalog (ARC) of the National Archives and Records Administration under the ARC Identifier 535626.

- ^ "Black Man" lyrics in website of www.sing.com Accessed August 7, 2008.

- ^ Description of Pierce's Almanac of 1639 in Bancroft, G., "History of the United States", Boston, C. Bowen, 1837-, cited in biography of Captain William Pierce in website of Pierces.org Accessed August 7, 2008.

- ^ "Clockmakers" in Historical Reference on Vintage & Antique Clocks, 08/07/08 in website of Antique-antiques Accessed August 7, 2008.

- ^ Letter from Mayor Adrian M. Fenty to Edmund C. Moy, Director, United States Mint, June 19, 2008, regarding the District's selection of Edward Kennedy ("Duke") Ellington for the reverse side of the U.S. Quarter Dollar coin for the District of Columbia in news release from the Office of the Secretary of the District of Columbia entitled "DC Announces Results of Online Quarter Vote" Accessed August 8, 2008.

- ^ Coordinates of Benjamin Banneker Park: 38°52′54″N 77°01′34″W / 38.8817128°N 77.0259833°W

- ^ Brochure: Southwest Heritage Trail in official website of Cultural Tourism DC, 1250 H Street, NW, Washington, DC 20005 Accessed August 6, 2008.

- ^ "BENJAMIN BANNEKER PARK, BANNEKER CIRCLE" in official website of DC Preservation League Accessed August 6, 2008.

- ^ "The Memorial" page in official website of the Washington Interdependence Council: Administrators of the Benjamin Banneker Memorial Accessed August 6, 2008.

- ^ COMCAST NEWS MAKERS video of Washington Interdependence Council's November 8, 2006, charette for Benjamin Banneker Memorial in official website of the Washington Interdependence Council: Administrators of the Benjamin Banneker Memorial Accessed August 6, 2008.

References

- Bedini, Silvio A., The Life of Benjamin Banneker. Scribner, New York, 1971, c1972. ISBN 0-684-12574-9.

- Cerami, Charles A., Benjamin Banneker: Surveyor, Astronomer, Publisher, Patriot (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 2002) ISBN 0-471-38752-5.