Anti-nuclear movement in Australia

The anti-nuclear movement in Australia can look back on years of development. The nuclear weapons tests , uranium mining and exports of Australia and the numerous incidents involving the use of nuclear energy have been the subject of frequent public debates in Australia . The roots of this anti-nuclear movement lie in the dispute over the French nuclear weapons tests in the Pacific from 1972 to 1973 and in the debate from 1976 to 1977 over uranium mining in Australia.

Some environmental groups formed in the mid-1970s after the nuclear incidents in nuclear power plants , such as the Movement Against Uranium Mining and Campaign Against Nuclear Energy (CANE), which cooperated with other environmental groups, such as the Friends of the Earth Australia and the Australian Conservation Foundation . A resurgence of this movement developed in 1983 when the newly elected Labor Government did not stop uranium mining - contrary to its earlier promises. When the price of uranium fell and the cost of nuclear power increased in the late 1980s , it appeared that the anti-nuclear movement had been successful, so the CANE organization disbanded itself in 1988.

When the supporters of the use of atomic energy declared that this use could contribute in part to solving the problem of global warming , the Australian government showed renewed interest in nuclear energy. Opponents and some scientists from Australia pointed out that nuclear energy in Australia cannot replace the abundant sources of energy and that uranium mining itself is a significant source of greenhouse gases .

To date (2011) Australia has not operated a nuclear power plant and has not yet built any nuclear weapons. The last failed attempt to build a nuclear power plant - the Jervis Bay Nuclear Power Plant - was in 1970.

Julia Gillard's Australian Labor Party (ALP), which ruled in 2011, is against the construction of nuclear weapons and in favor of the construction of a fourth uranium mine, which the 2009 ALP National Conference decided on.

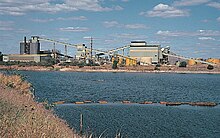

Uranium is currently being mined in Australia at the Olympic Dam mines , Beverley - both in northern South Australia , and the Ranger uranium mine in the Northern Territory . In April 2009, development of the Honeymoon Uranium Mine , another uranium mine located in South Australia, began.

Australia has been operating a HITAR research reactor since 1958 and has been operating a research reactor from 2007 , the Open Pool Australian Lightwater Reactor (OPAL) in Lucas Heights , a district of Sydney .

history

1950s and 1960s

In 1952, the Australian government opened the Rum Jungle uranium mine , 85 km south of Darwin , the ancestral Aborigines were not consulted and the mine site became an ecological debacle. In 1952, the Conservative government of Robert Menzies , led by the Liberal Party , passed the Defense (Special Undertakings) Act 1952 , which allowed the government of Great Britain to carry out surface nuclear tests in remote areas of Australia. The first nuclear test in Australia took place on October 15, 1953 in the Woomera Prohibited Area . Further tests were carried out in Maralinga at Emu Fields in South Australia between 1955 and 1963. The truth about the legal and political implications, as well as the consequences for the environment and for the Aborigines in the area of these test programs, crystallized only in the course of time. The secrecy of the UK's nuclear testing program and the remoteness of the test sites meant that public awareness of the risks in Australia grew very slowly.

When the Ban the Bomb movement emerged in Western societies during the 1950s, Australian resistance to British nuclear tests also grew. An opinion poll conducted in 1957 showed that 49% of the Australian public were against these tests and only 39% were in favor. In 1964 there were peace marches with the posters "Ban the Bomb" in various major cities in Australia.

In 1969 the first Australian nuclear power plant with a capacity of 500 megawatts was planned: The Jervis Bay nuclear power plant, on the Jervis Bay Territory 200 km south of Sydney . A local opposition campaign was formed and the South Coast Trades and Labor Council , which organizes workers in the area, said it would refuse to help build the reactor. Environmental studies and further preparatory work on the area had been completed, two bids had been opened, the tender documents had been examined and the first foundation work had been completed, but the Australian government decided in 1971 not to pursue the project for various reasons, mainly for economic reasons.

1970s

The political controversy over France's 1972-1973 nuclear test in the Pacific mobilized some Australian groups and unions. In 1972, the International Court of Justice of Australia and New Zealand because of the nuclear tests of France on the atoll of Mururoa called. In 1974 and 1975 the uranium mining in Australia got into the political dispute and local groups of the Friends of the Earth Australia were founded. The Australian Conservation Foundation also started speaking out on uranium mining again and supported grassroots activists . The environmental impact of uranium mining and poor waste management at the first Rum Jungle uranium mine sparked extensive environmental discussions in the 1970s. The Australian anti-atomic force movement was given further momentum by comments from various personalities on the nuclear option, such as nuclear scientists Richard Temple and Rob Robotham and the writers Dorothy Green and Judith Wright .

A report by Russell Fox in 1976 and 1977 made uranium mining the focus of public political controversy. Some environmental groups were formed as a result of incidents at nuclear power plants, such as the Movement Against Uranium Mining , which was founded in 1976 when the Campaign Against Nuclear Energy took place in South Australia in 1976 . These groups also collaborated with other environmental groups such as Friends of the Earth Australia and the Australian Conservation Foundation .

In November and December 1976 7,000 people marched through Australian cities protesting against uranium mining. In April 1977 the first national demonstration took place, coordinated by the Uranium Moratorium organization, which took about 15,000 demonstrators in Melbourne , 5,000 in Sydney and more in other Australian cities. In an important national collection of signatures, over 250,000 signatures for a 5-year moratorium were collected. In August of the same year, 50,000 people demonstrated nationwide and the opposition to uranium mining developed political strength.

When the Australian Labor Party (ALP) favored an infinitive moratorium on uranium mining at a national conference in 1977 , the anti-nuclear movement decided to support the ALP in the upcoming election. However, there was a setback when another ALP conference decided on a "one mine policy" (German: "Eine-Mine-Politik") and when the ALP won the 1983 election, another ALP conference voted for a " three mines policy "(German:" Drei-Minen-Politik "). This decision resulted in the retention of the three uranium mines in operation at the time, the Nabarlek Uranium Mine , Ranger Uranium Mine and Olympic Dam . This also meant the continuation of the existing mining contracts, but the opening of new uranium mines was excluded.

1980s and 1990s

Between 1979 and 1984 was Kakadu National Park , which lies at the Ranger uranium mine and one of the few Australian sites in the rank of UNESCO - World Natural and - world cultural heritage is largely developed. The contradiction between natural and cultural interests and uranium mining led to long-lasting tensions in this area. These disputes led to a demonstration march in Sydney on Hiroshima Day 1980 , supported by Movement Against Uranium Mining (MAUM), where "Keep uranium in the ground" (German: "Let the uranium in the ground") and "No to nuclear war" (German: "No" to nuclear war) was demanded. Later that year, the Sydney city council officially declared the city a nuclear-weapon-free zone in an overarching action , and numerous other municipal assemblies in Australia joined the campaign.

In the 1980s, academics like Jim Falk criticized the "deadly connection" between uranium mining, nuclear reactors and nuclear weapons and described Australian nuclear policy as the connection between the "proliferation of weapons of mass destruction" and the "plutonium" Economy ".

On Palm Sunday 1982, about 100,000 Australians took part in anti-nuclear force demonstrations in the country's largest cities. These events grew continuously to 350,000 demonstrators by 1985. This movement focused on Australia's continued uranium mining and exports, calling for a nuclear weapon ban, the removal of foreign military bases on Australian soil and a nuclear-free Pacific. Opinion polls showed that half of the Australian population was in opposition to uranium mining and export, as was the stay of US nuclear warships in Australia. According to public opinion polls, 72% of the population believed that nuclear weapons should be banned and 80% favored the creation of a world without nuclear energy.

A Nuclear Disarmament Party won a seat in the Australian Senate in 1984 but soon disappeared from the political scene. The ALP-led governments of Bob Hawke and Paul Keating (1983–1996) were “ uneasy standoff in the uranium debate ” (German: “ uneasy in the stalemate of the uranium debate”). Although the ALP recognized the community spirit against uranium mining, it was reluctant to oppose the mining industry.

On Palm Sunday 1986, 250,000 people took part in anti-nuclear force demonstrations in Australia. In Melbourne , the seafarers' union, Seaman's Union of Australia , boycotted work for foreign nuclear warships.

Australia's only nuclear engineering school, the former School of Nuclear Engineering at the University of New South Wales closed in 1986.

In the late 1980s, the price of uranium fell and the cost of using nuclear power increased, and it appeared that the anti-nuclear movement was successful and eventually the anti-nuclear movement in Australia disintegrated on its own two years after the Chernobyl disaster.

Government policy was against the opening of new uranium mines until the 1990s, but there were occasional public discussions about it. After a protest march in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane , the opening of a new uranium mine in the Jabiluka mine was prevented in 1998.

In 1998 there was a plan by Pangea Resources , an international consortium, to landfill nuclear waste in Western Australia . This plan called for 20% of the world's garbage, nuclear fuel and nuclear weapons to be dumped there. This concept was "publicly condemned and abandoned" (German: "publicly rejected and abandoned")

2000s

In 2000, the Ranger uranium mine in the Northern Territory and the Olympic Dam mine in South Australia were operational and the Nabarlek uranium mine had been closed. A third uranium mine, the Beverley , was in operation. Various advanced plans for uranium mining such as the Honeymoon uranium mine in South Australia, the Jabiluk uranium mine in the Northern Territory and the Yeeliree uranium mine in Western Australia had been halted because of political and Aboriginal opposition .

In May 2000, an anti-nuclear demonstration was held at the Beverley uranium mine by 100 protesters. Ten of the protesters were ill-treated by police and later sued by the South Australia government for AUD $ 700,000 in damages .

According to the McClelland Royal Commission report , a complete decontamination had to be carried out at Marlalinga in the outback of South Australia because of the British atomic bomb tests in the 1950s, which cost more than AUD $ 100 million. There was only controversy about the methods and success of the measure.

Uranium prices rose from 2003 onwards, and when nuclear energy supporters came out in favor of using it in the face of global warming, the Australian government showed interest. However, in June 2005 the Australian Senate passed a motion against the use of nuclear energy. As a result, the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Industry and Resources issued a report on the use of nuclear energy in Australia, which was positive. In late 2006 and early 2007, Prime Minister John Howard's statements were reported in favor of nuclear power for environmental reasons.

In view of the advocacy of using nuclear power as a possible alternative to climate change, the opponents of nuclear energy and scientists countered that nuclear energy in Australia cannot be significantly replaced by other energies and that uranium mining itself results in significant greenhouse gas emissions . The anti-nuclear power campaigns publicly spread concerns about possible reactor locations: These fears took advantage of the anti-nuclear power parties and this led to the success of the 2007 national election. The laboratory government of Kevin Rudd was elected in November 2007 and decided against the use of atomic energy. The anti-nuclear movement resumed its activity in Australia, expanding its opposition to the existing uranium mines, working against the development of nuclear power and criticizing the advocates of nuclear waste disposal.

In October 2009 the Australian government pursued plans to store nuclear waste in the Northern Territory. However, there was opposition from the indigenous people there, the government of the Northern Territory and most of the population of that state. In November 2009, 100 anti-nuclear movement protesters gathered in front of the House of Parliament for a sit-in in Alice Springs , demanding that the Northern Territory government not approve the opening of a mine on the nearby uranium deposit.

In early April 2010, more than 200 environmentalists and Aboriginal people gathered in Tennant Creek to protest the nuclear waste dump being built at Muckaty Station in the Northern Territory.

Western Australia has a significant Australian uranium resource that was subject to a state ban on exploitation between 2002 and 2008. The Liberal Party loosened this spell when it was in power and numerous companies explored these deposits. One of the world's largest mining companies, BHP Billiton , plans to develop the Yeelirrie uranium deposit in 2011 in a $ 17 billion project.

Towards the end of 2010 there was Australian debate over whether the nation should use nuclear power as part of an energy mix. Nuclear power seems to be " a divisive issue that can arouse deep passions among those for and against " (German: a "polarizing matter that generates deep passion between those who are for or against"),

Decision against the repository at Muckaty Station

In June 2014 the Australian government announced that it would no longer adhere to the plan for the repository at Muckaty Station. This was preceded by a lawsuit against the agreement concluded in 2007 between the government and the Ngapa clan to set up a repository for nuclear waste from Sydney's medical and research reactors. Among other things, the Northern Land Council had sued against it.

Nuclear incidents

Because of the environmental, political, economic, social and cultural problems, the deficiencies of nuclear power as an energy source and the lack of sustainable energy policy, nuclear power and uranium mining are rejected in Australia. The most weighty reason for rejection, however, is seen in the proliferation of nuclear weapons of mass destruction . For example, the Ranger Report found that: " The nuclear power industry is unintentionally contributing to an increased risk of nuclear. This is the most serious hazard associated with the industry ". (German: The nuclear industry inadvertently contributes to an increased risk of nuclear war. This is the greatest danger associated with this industry.)

The health risks associated with the use of atomic energy and materials play an important role in the Australian anti-nuclear campaign. This became evident in the case of the Chernobyl disaster, but for Australians the dispute over the atomic bomb tests in Australia and the Pacific plays a special role as a local factor that can be traced back to a well-known opponent of nuclear exploitation, Helen Caldicott , a medical professional .

The economic use of nuclear energy is questionable because this use is uneconomical for Australia, especially since coal is in abundance in Australia.

The nuclear industry in Australia has produced a total of 3,700 m³ of nuclear waste in the past 25 years, which is stored in more than 100 locations and 45 m³ are added every year. There is no sustainable strategy for nuclear waste storage in Australia.

From the perspective of the anti-nuclear movement, today's problems with nuclear power are mostly the same problems as they were in the 1970s. This movement argues that nuclear power plants pose the risk of incidents and that there is no solution for long-term storage of nuclear waste. The proliferation of weapons of mass destruction continues, which can be seen after the construction of nuclear power plants and the acquired expertise in the operation of nuclear plants in Pakistan and North Korea . The alternatives to nuclear power are more efficient energy use and renewable energies , particularly wind power , which promotes the development of a renewable energy industry.

Public opinion

An opinion poll carried out by the Uranium Information Center in 2009 found that Australians between the ages of 40 and 55 form the age group who are "most trenchantly opposed to nuclear power" (German: most sharply opposed to nuclear power). This generation was shaped by the Cold War , the anti-nuclear movement experience of the 1970s, the nuclear disasters of the reactor on Three Mile Island in the USA in 1979 and that of Chernobyl in 1986. It's the generation that has also been under the cultural influence of films made against the use of nuclear power, such as The China Syndrome and Silkwood and the apocalyptic Dr. Strangelove . Younger people are "less resistant" (German: less resistant) to the idea of using nuclear power in Australia.

Indigenous landowners are unanimously against uranium mining, saying it is having a negative impact on their communities.

Active groups

- Anti-Nuclear Alliance of Western Australia

- Australian Conservation Foundation

- Australian Nuclear Free Alliance , an Aboriginal-led organization that educates indigenous people about the dangers of using nuclear power on their land.

- Cycle Against the Nuclear Cycle

- EnergyScience

- Friends of the Earth

- Greenpeace Australia Pacific

- Kupa Piti Kungka Tjuta

- Mineral Policy Institute

- Peace Organization of Australia

- The Australia Institute

- The Sustainable Energy and Anti-Uranium Service Inc.

- The Wilderness Society

Personalities

Below are some prominent Australian figures who have publicly opposed the use of nuclear energy:

literature

- Greg Adamson: Stop Uranium Mining! Australia's Decade of Protest . Resistance Books, 1999, ISBN 978-0-909196-89-9 ( limited preview in Google Book Search - the history of the anti-nuclear movement in Australia from the 1970s and 1980s).

- Stephanie Cooke : In Mortal Hands: A Cautionary History of the Nuclear Age , Black Inc, 2009.

- Mark Diesendorf: Climate Action: A Campaign Manual for Greenhouse Solutions , University of New South Wales Press, 2009.

- Mark Diesendorf : Greenhouse Solutions with Sustainable Energy , University of New South Wales Press, 2007.

- David Elliott : Nuclear or Not? | Nuclear or Not? Does Nuclear Power Have a Place in a Sustainable Energy Future? Palgrave, 2007.

- Jim Falk: Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power , Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Marco Giugni: Social Protest and Policy Change: Ecology, Antinuclear, and Peace Movements in Comparative Perspective , Rowman and Littlefield, 2004.

- Amory Lovins : Soft energy path | Soft Energy Paths: Towards a Durable Peace , Friends of the Earth International, 1977, ISBN 0-06-090653-7

- Amory B. Lovins, John H. Price: Non-Nuclear Futures: The Case for an Ethical Energy Strategy , Ballinger Publishing Company, 1975, ISBN 0-88410-602-0

- Ian Lowe : Reaction Time: Climate Change and the Nuclear Option , Quarterly Essay , 2007.

- Alan Parkinson: Maralinga: Australia's Nuclear Waste Cover-up , ABC Books, 2007.

- Ron Pernick , Clint Wilder : The Clean Tech Revolution: The Next Big Growth and Investment Opportunity. Collins, 2007, ISBN 978-0-06-089623-2 .

- Mycle Schneider , Steve Thomas , Antony Froggatt, Doug Koplow: The World Nuclear Industry Status Report. Ministry of the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety , 2009.

- Jennifer Smith (Ed.): The Antinuclear Movement. Cengage Gale, 2002.

- J. Samuel Walker: Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective. University of California Press, 2004.

Web links

- Current criticism of the use of nuclear power by Australian scientists

- Australian map of nuclear weapons tests in Australia

- Nuclear Knights , a book about the opponent of the use of nuclear power Brian Martin

- Strategy against nuclear power , an anti- nuclear power strategy published by Friends of the Earth .

- Backs to the Blast, an Australian Nuclear Story , a documentary about nuclear testing in Australia.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jim Green: Australia's anti-nuclear movement: a short history ( Memento of the original from April 5, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Green Left Online, August 26, 1998. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ↑ a b Jason Koutsoukis: Rudd romps to historic win . The Age , November 25, 2007. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ^ A b c Roy McLeod: Resistance to Nuclear Technology: Optimists, Opportunists and Opposition in Australian Nuclear History. In: Martin Bauer (Ed.) Resistance to New Technology. Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 171-173.

- ^ A b Drew Hutton, Libby Connors: A History of the Australian Environmental Movement , Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- ^ Strategy against nuclear power . Friends of the Earth (Canberra), January 1984.

- ^ A b c Roy McLeod: Resistance to Nuclear Technology: Optimists, Opportunists and Opposition in Australian Nuclear History. In: Martin Bauer (Ed.) Resistance to New Technology. Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 175-177.

- ↑ a b Mark Diesendorf: Paths to a Low-Carbon Future: Reducing Australia's Greenhouse Gas Emissions by 30 per cent by 2020 . 2007 (PDF).

- ↑ a b Jim Green: Nuclear Power: No Solution to Climate Change ( Memento of the original from September 25, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . 2005 (PDF)

- ^ Sarah Martin: Peter Garrett says Four Mile uranium mine decision not taken lightly . The Advertiser Adelaide, July 15, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2011

- ↑ Work begins on Honeymoon uranium mine . ABC News, April 24, 2009. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ↑ a b c Justine Vaisutis: Indigenous communities getting dumped into it. Again. In: Habitat Australia , Vol. 38, No. 2, 2010, p. 22.

- ^ A b A toxic legacy: British nuclear weapons testing in Australia . Australian government. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ↑ Women with Ban the Bomb banner during Peace march on Sunday 5 April 1964, Brisbane, Australia . Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ↑ Girl with placard Ban nuclear tests during Peace march on Sunday April 5, 1964, Brisbane, Australia . Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ↑ Jim Falk Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power. 1982, p. 260.

- ↑ Gorton gave nod to nuclear power plant. The Age, January 1, 2000.

- ^ A b c d e Brian Martin: The Australian anti-uranium movement . In: Alternatives: Perspectives on Society and Environment , Volume 10, Number 4, 1982, pp. 26-35. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ↑ Kate Dewes, Robert Green: Aotera / New Zealand at the World Court ( Memento of the original from May 26, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 2.1 MB). The Raven Press, 1999, pp. 11-15.

- ↑ a b Martin Bauer (Ed.): Resistance to New Technology , Cambridge University Press, 1995, p. 173.

- ^ A b Jim Falk: Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power. 1982, pp. 264-265.

- ↑ Alice Cawte: Atomic Australia 1944-1990 , New South Wales University Press, 1992, p. 156.

- ^ Verity Burgmann: Power, profit, and protest: Australian social movements and globalization . Allen & Unwin, 2003, ISBN 978-1-74114-016-3 , pp. 174–175 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Chris Evans: Labor & uranium: an evolution. Laboratory E-herald. March 23, 2007.

- ^ A b c d Lawrence S. Wittner: Nuclear Disarmament Activism in Asia and the Pacific, 1971-1996 . The Asia-Pacific Journal , Vol. 25-5-09, June 22, 2009.

- ↑ a b c d e Four Corners : Chronology - Australia's Nuclear Political History ( Memento of the original from April 20, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . 2005, Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ↑ a b c d Brian Martin: Opposing nuclear power: past and present . In: Social Alternatives. 26, No. 2, pp. 43-47, 2007. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ↑ a b c Anti-uranium demos in Australia . BBC News, April 5, 1998. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ↑ a b Vassilios Agelidis: Too late for nuclear ( Memento of the original from December 9, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . ABC News, December 7, 2010.

- ^ Ian Holland: Waste Not Want Not? Australia and the Politics of High-level Nuclear Waste. In: Australian Journal of Political Science. 37, No. 2, pp. 283-301, 2002.

- ↑ Anti-nuke protesters awarded $ 700,000 for 'feral' treatment . Sydney Morning Herald, April 9, 2010.

- ↑ Australia's uranium - Greenhouse friendly fuel for an energy hungry world ( Memento of the original from August 5, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . House of Representatives Standing Committee on Industry and Resources, 2006. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ↑ Matthew Franklin, Steven Wardill: PM nukes lab's "campaign of fear". Courier-Mail, June 6, 2006.

- ↑ Joseph Kerr, Steve Lewis: Support for N-power plants falls. The Australian, December 30, 2006.

- ↑ Ty Pedersen: Olympic Dam expansion: a risk too great ( Memento of the original from January 30, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Green Left Weekly, January 26, 2008. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ↑ Anti-nuclear campaigners say Muckaty will be dumped. ABC News, Nov. 26, 2007.

- ^ Dave Sweeney: Australia's Nuclear Landscape. In: Habitat Australia. October 2009, pp. 15-16.

- ↑ Kirsty Nancarrow: 100 protest in Alice against uranium mine . ABC News, Nov. 24, 2009.

- ^ Hundreds rally to stop nuclear dump . ABC News, April 5, 2010.

- ↑ Jessie Boylan: Australia's aboriginal communities clamor against uranium mining . The Guardian, Aug. 9, 2010.

- ↑ Aborigines prevent nuclear waste dumps . Die Tageszeitung website, June 19, 2014. Accessed June 19, 2014.

- ↑ cf. Brian Martin: Nuclear Power and the Western Australia Electricity Grid. In: Search. Vol. 13, No. 5-6, 1982.

- ^ Australia's uranium . World Nuclear Association (January 2011). Retrieved February 10, 2011

- ^ Radioactive waste repository & store for Australia . World Nuclear Association, October 2007 :. Retrieved February 10, 2011

- ^ A b c Geoff Strong, Ian Munro: Going Fission . The Age , October 13, 2009.

- ^ Anti-Nuclear Alliance of Western Australia. Anti-Nuclear Alliance of Western Australia. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ Australian Conservation Foundation. Nuclear Free ( Memento of the original from December 22, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ↑ Australian Nuclear Free Alliance ( Memento of the original from February 26, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ Australian Conservation Foundation. Australian Nuclear Free Alliance ( Memento of the original from March 13, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ New alliance to mount anti-nuclear election fight ABC News , August 13, 2007. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ Cycle Against the Nuclear Cycle. Cycle Against the Nuclear Cycle ( Memento of the original dated November 3, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ↑ Energy Science. The Energy debate . Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ Australian Nuclear Issues . Retrieved May 5, 2010

- ^ Greenpeace Australia Pacific. Nuclear power ( Memento of the original from October 31, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ Friends of the Earth International (2004). Aboriginal women win battle against Australian Government ( Memento of the original dated May 11, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ The Australia Institute. Nuclear Plants - Where would they go? ( Memento of the original from September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 29 kB) Media release , January 30, 2007. Accessed May 5, 2010.

- ↑ The Sustainable Energy and Anti-Uranium Service Inc. The Sustainable Energy and Anti-Uranium Inc. Service . Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ The Wilderness Society. The Nation said YES! to a Nuclear Free Australia ( Memento of the original from July 18, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ The Wilderness Society launches new anti-nuclear TV Ad . Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ↑ JA Camilleri. The Myth of the Peaceful Atom ( Memento of the original from September 14, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 170 kB) Journal of International Studies , Vol. 6, No. August 2, 1977, pp. 111-127.

- ↑ Bill Williams. Nuclear delusions keep mushrooming The Age , October 15, 2009.

- ↑ James Norman and Bill Williams. Stars align in quest to rid the world of nukes The Age , September 24, 2009.