Education system in Malaysia

The educational system in Malaysia is under the Ministry of Education ( Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia ). It is divided into two main departments, of which the Education Sector deals with all matters relating to pre-schools, primary and secondary schools, while the Higher Education Sector is responsible for the universities . Although the federal government is responsible for education policy, every Malaysian state has its own ministry of education . The legal basis for government education policy is the Education Act 1996 .

Malaysia has a publicly owned school system that guarantees free multilingual education to all citizens. There is also the option of attending a private school or taking part in homeschooling . Compulsory schooling is limited to primary level. As in many Asia-Pacific countries, such as South Korea , Singapore and Japan , the curricula and final exams follow a uniform, cross-school system.

history

The Sekolah Pondok (literally hut school ), the madrasa and other Islamic schools were the oldest forms of school in Malaysia. Early works of Malay literature, such as Munshi Abdullah's autobiography Hikayat Abdullah, mention these schools and prove that they preceded the secular school model.

Secular schools emerged in Malaysia through the British colonial government. Many of the country's oldest schools were founded in the Penang , Malacca and Singapore Straits Settlements . The oldest English-speaking school in Malaya was the Penang Free School , founded in 1816, followed by Malacca High School and the Anglo-Chinese School in Klang . Many of these old schools are highly regarded.

The British historian Richard O. Winstedt played an important role in improving the education of the Malays and played a leading role in setting up the Sultan Idris Training College , which should serve to train teachers of Malay origin. Richard James Wilkinson established the Malay College Kuala Kangsar in 1905 , whose task it was to educate the Malay elite.

Originally, the British colonial government refused to support Malaysian-language secondary schools and forced those who had only learned Malaysian in primary school to adapt to English-language instruction. Many Malaysians willing to educate failed at this hurdle. Despite complaints about this regulation, the British Director of Education stated :

“It would be contrary to the considered policy of government to afford to a community, the great majority of whose members find congenial livelihood and independence in agricultural pursuits, more extended facilities for the learning of English which would be likely to have the effect of inducing them to abandon those pursuits. "

In both the Federal Council and the Singapore Legislative Assembly, Malay MPs vehemently protested the statement, which one of them described as "British policies that make Malaysians unemployed by banning them from learning Malaysia's language for work."

“In the fewest possible words, the Malay boy is told 'You have been trained to remain at the bottom, and there you must always remain!' Why, I ask, waste so much money to attain this end when without any vernacular school, and without any special effort, the Malay boy could himself accomplish this feat? "

To remedy this problem, the British government founded the Malay College Kuala Kangsar . However, the purpose of the school was to train simple and middle service officials rather than to open the door to trade for the Malays - and it was never intended to prepare its students for higher education .

Christian missionaries such as the Mission Society of St. Joseph von Mill Hill , the Brothers of the Christian Schools , Marist School Brothers , Adventists , Anglicans, and Methodists founded a variety of mission schools offering primary and secondary education in English. Most of these schools were single- educational schools. Although today they have been fully integrated into Malaysian-speaking national schools and although access to these schools is possible regardless of gender, origin or religious background, many of these schools still bear their original names in which the names of saints or religiously connoted words such as "Catholic", "Convention", "Advent" and "Methodist" are included.

Large numbers of Chinese and Indians immigrated to Malaya during the British colonial period. These groups ran their own schools, used their own curricula, and hired teachers from their own ranks.

In the 1950s, four different proposals were on the table for the necessary restructuring of the education system: The Barnes Report , favored by the Malays , the Ordinance Report, which consisted only of a modified Barnes Report, the Fenn-Wu Report , which was supported by the Chinese and Indians and the Razak Report , which was a compromise between the two proposals. Against the protest of the Chinese, Barnes' proposal was implemented in 1952 by the Education Ordinance 1952 . In preparation for the establishment of an independent Malaya, the education system was converted to the Razak Report in 1956. The Razak Report called for a system of national schools with the languages of instruction Malay, English, Chinese and Tamil in the primary level and Malay and English in the secondary level. It also included a national curriculum that was independent of the language of instruction. Schools with Malaysian as the language of instruction should be classified as "National Schools", all others as "National-type Schools".

In the earlier years of independence, the Chinese and Tamil-speaking schools and the mission schools received financial support from the government and were allowed to keep the language of instruction if they accepted the national curriculum. The Chinese-speaking secondary schools had to choose either to receive state support and become a "national-type school" or to continue to exist as a private school without state support. Most schools accepted the change; the others continued their work as a Chinese Independent High School . Shortly after the move, some of the new national-type schools established a Chinese Independent High School as a branch.

In accordance with Malaysian language policy, the government began converting all English-speaking national-type schools into Malaysian-speaking national schools in the 1970s. This conversion affected the first graders of the following years, so that a gradual introduction took place. The complete transfer to the new system was therefore not completed until the end of 1982.

In 1996, the Education Act 1996 came into effect, replacing the Education Ordinance 1956 and Education Act 1961 .

Grade levels

The school year is divided into two semesters. The first semester starts in January and ends in June, the second starts in July and ends in December.

| Name of the class level | Typical age |

|---|---|

| Preschool | |

| Preschool playgroup | 3-4 |

| kindergarten | 4-6 |

| Primary school | |

| Standard 1 or Tahun 1 or Darjah 1 | 7th |

| Standard 2 or Tahun 2 or Darjah 2 | 8th |

| Standard 3 or Tahun 3 or Darjah 3 | 9 |

| Standard 4 or Tahun 4 or Darjah 4 | 10 |

| Standard 5 or Tahun 5 or Darjah 5 | 11 |

| Standard 6 or Tahun 6 or Darjah 6 | 12 |

| Secondary school | |

| Form 1 | 13 |

| Form 2 | 14th |

| Shape 3 | 15th |

| Form 4 | 16 |

| Shape 5 | 17th |

| Shape 6 | 18-19 (possible in some schools) |

| Tertiary education | |

|

College or University The individual years of a four-year degree are sometimes referred to as the Freshman Year, Sophomore Year, Junior Year, and Senior Year. |

No defined age. |

School types

Preschool education

There are no set rules as to when a child needs to start preschool education , but the majority start at the age of five. The school education can start earlier, with 3–6 years in kindergarten . Pre-school education usually lasts for two years and ends with school enrollment at the age of 7. There is no curriculum for pre-school education, but training and certification are required to run a pre-school or to work as a teacher there. The training covers child psychology , didactics and other relevant topics related to child welfare and child development.

Pre-school education is mostly offered by private companies, but also church groups and a few state organizations are active here. Some primary schools have attached preschool departments. The acceptance of pre-school programs varies; While people in urban areas can send their children to private kindergartens, this rarely happens in rural areas. Registered preschools are subject to territorial division and must comply with the relevant health and fire protection regulations. Many preschools are located in densely populated areas and were originally normal residential buildings that were converted into schools.

Primary level

The primary level (primary education) begins with the age of seven and six years. The classes are counted consecutively from 1 to 6 and given the prefix Tahun ("year") or Darjah ("standard"). Tahun 1 to Tahun 3 are referred to as level I ( tahap satu ) and Tahun 4 to Tahun 6 as level II ( tahap dua ). The move to the next year takes place regardless of school performance.

From 1996 to 2000, at the end of Level I, students took the Penilaian Tahap Satu (PTS) exam . Passing this test allowed the student to skip the fourth year and go straight to Tahun 5 . However, the test was abolished in 2001 because it was feared that it would lead parents and teachers to put unnecessary pressure on the students to succeed.

At the end of level II of primary school, all pupils take the primary school final test ( Ujian Pencapaian Sekolah Rendah , UPSR) at the end of the sixth year . Spelling and language comprehension of the Malaysian language, English, natural sciences and mathematics are tested. In addition to these five subjects, there are comprehension tests and spelling tests for Chinese for students in Chinese-speaking schools and a corresponding test for Tamil for Tamil-speaking schools.

School types and language of instruction

The public primary schools are divided into two categories according to the language of instruction:

- Malaysian- speaking national schools ( National Schools , Sekolah Kebangsaan , SK)

- non-malaysischsprachige National Schools ( National-type schools , Sekolah Jenis Kebangsaan , SJK), also known as People's Language Schools ( vernacular schools ) announced that turn into

- Chinese-speaking ( National-type School (Chinese) , Sekolah Jenis Kebangsaan (Cina) , SJK (C) for short) or

- Tamil ( National-type School (Tamil) , Sekolah Jenis Kebangsaan (Tamil) , SJK (T) for short).

All schools accept students without restrictions on their race or language background.

Malaysian and English are compulsory subjects in all schools. For non-linguistic subjects, the same curriculum is used in all schools regardless of the language of instruction. Learning Mandarin is compulsory in the SJK (C), just as Tamil is a compulsory subject in the SJK (T). Tamil and Mandarin must also be offered in a Malaysian-speaking national school as soon as parents of more than 15 students request it; the same is true of the indigenous languages spoken in Malaysia.

In January 2003, English was introduced as the language of instruction in science and mathematics. Due to political pressure from the Chinese population, science and mathematics were taught in both English and Chinese in the SJK (C). In 2009, the government reversed its decision, so that from 2012 the original language regulations applied again.

For public funding, the National Schools are owned and operated by the government. National-type schools are only funded by the state: while the state finances the teaching operations, takes over the training and payment of the teachers and sets the curriculum, the real estate of the school and the fixed assets are owned by the local, ethnically-based communities which the board of directors to watch over the school property. Between 1995 and 2000 the budget for the development of primary education in the " Seventh Malaysia Plan " was divided in such a way that the National Schools 96.5%, the Chinese National-type Schools 2.4% and the Tamil National-type Schools 1% Received budgets, despite the fact that only 75% of students went to national schools, while Chinese-language schools taught 21% and Tamil-language schools taught 3.6% of students.

There were other types of non-Malaysian language schools in earlier years. The former English National-type Schools were integrated into the national schools as a result of decolonization . Other schools, such as those whose language of instruction was Punjabi , were closed due to dwindling student numbers. The care of Punjabi and the associated culture is currently carried out outside of school in the Gurdwara of the Malaysian Sikh .

The division of the primary school education system into Malaysian-speaking and non-Malaysian-speaking schools has been criticized for allegedly creating a racially motivated polarization at an early stage in life. To counter the problem, experimental Sekolah Wawasan ("vision schools") were set up. With this concept, three schools - typically one SK, one SJK (C) and one SJK (T) each - share the same premises and school facilities, but retain their own administration. However, the model found little acceptance among the Chinese and Indian populations, as they feared restricted use of their mother tongues.

Secondary school

The secondary (secondary education) in Malaysia (by the National Secondary English. National Secondary Schools , times. Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan abbreviated SMK ) covered. National secondary schools use Malaysian as the main language of instruction. English is a compulsory subject in all schools. English was introduced experimentally in 2003 as the language of instruction in mathematics and science subjects, but in 2009 the government decreed that from 2012 these subjects should be taught in Malaysian again.

As in primary education, National Secondary Schools must offer Chinese, Tamil and Indigenous Languages if the parents of more than 15 students so wish. In addition, certain schools can include other languages such as Arabic , Japanese , German or French in the curriculum.

The secondary level lasts five years and is referred to as grades 1 to 5 (English form 1-5 , mal. Tingkatan 1-5 ). Grades 1 to 3 correspond to secondary level I ( Lower Secondary or Menengah Rendah ), while grades 4 and 5 correspond to secondary level II ( Upper Secondary or Menengah Atas ). The majority of students have direct admission to the Form 1 class after completing primary school . Pupils from non-Malaysian- speaking primary schools must pass the primary school final test UPSR with at least grade "C", otherwise attending a one-year transition class ( Remove or Kelas / Tingkatan Peralihan ) before switching to Form 1 is mandatory. As in the primary level, promotion within the secondary level takes place regardless of academic performance.

From secondary school onwards, all students are required to demonstrate participation in at least two co-curricular activities - i.e. activities that go beyond the curriculum - in Sarawak even three. The offers for these activities vary from school to school. Competitions and demonstrations take place regularly. Co-curricular activities are often offered in the following categories: uniformed groups, performing arts, clubs, sports and games. Participation in more than two activities is possible.

At the end of grade 3, students take the Penilaian Menengah Rendah exam, or PMR for short, which was formerly known as Sijil Pelajaran Rendah (SRP) , Lower Certificate of Education (LCE), or Lower Secondary Evaluation . According to the PMR exam results, they find themselves in the upper secondary level either in a scientific or a humanities trait. The scientific trajectory is generally the more desirable one, since one can change to the humanities trajectory at any time, but rarely the other way around.

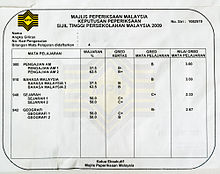

At the end of grade 5, the final exam Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia (SPM) or Malaysian Certificate of Education takes place.

A subset of the public secondary schools are the National-type Secondary Schools ( Sekolah Menengah Jenis Kebangsaan , SMJK). At the time of Malaya's independence in 1957, it had been decided that secondary education should be provided by Malaysian- speaking national secondary schools and English-speaking national-type secondary schools should be ensured. The government offered assistance to the fee-paying English-language schools belonging to the religious communities or mission societies if they would adopt the national curriculum. Secondary schools with other languages of instruction - most of them Chinese schools - also received funding if they were converted into English-speaking schools. When the government abolished English as the language of instruction in the 1970s, all national-type secondary schools were gradually converted into Malaysian - speaking schools. The term "National-type Secondary School" is not included in the Education Act 1996 , which led to a blurred separation between SMK and SMJK. This development has been criticized by Chinese interest groups; The clear positioning of the 78 former Chinese-speaking schools of other secondary schools continues to be demanded from this side. The schools still have the abbreviation "SMJK" in the school name and the respective Board of Directors continues to manage the school property - in contrast to the schools, which are run by the state. In addition, Chinese language teaching is one of the compulsory subjects taught during normal school hours, while other schools only offer such language courses outside of the timetable.

Other state or state-sponsored school types are religion-based secondary schools ( Sekolah Menengah Agama ), technology-oriented schools ( Sekolah Menengah Teknik ), boarding schools ( Sekolah Berasrama Penuh ) and the MARA Junior Science College ( Maktab Rendah Sains MARA ).

There are a few elite schools among public secondary schools. Access to these schools is selective and restrictive; The school places are reserved for students who consistently shine with outstanding performance in grades Standard 1 to Standard 6 . The elite schools are either all-day schools or boarding schools (asrama penuh) . Examples of such schools are Malacca High School , the Royal Military College, and the Penang Free School .

Residential schools or Sekolah Berasrama Penuh are also known as "science schools ". They were originally designed for the Malaysian elite, but are now dedicated to promoting those Malaysians who have distinguished themselves through exceptional academic or athletic achievements or through leadership skills. The schools are based on British boarding schools.

Post secondary education

After the SPM exam, students of public secondary schools the choice of either the secondary school with have form 6 to continue or at the Malaysian Matriculation Program (matriculation) participate.

Those who with Form 6 go on to take the final exam Sijil Tinggi Persekolahan Malaysia (STPM, Engl. Malaysian Higher School Certificate) part. The STPM is regulated and organized by the Malaysian Examinations Council . Although it is generally required as admission to the state universities in Malaysia, it is also recognized internationally and can also serve as admission for undergraduate courses ( undergraduate courses ) of the private universities are used.

The matriculation is a university pre-qualification program that is designed to prepare for study at a university. Participation is open to all secondary school graduates. Unlike the SPTM, the qualifications of the preparatory course are only valid at universities in Malaysia. The matriculation is a one- or two-year course organized by the Ministry of Education.

Since not all applicants are admitted to the preparatory course and the selection criteria are not transparent, there is always speculation about possible arbitrariness. The selection process also follows an ethnicity-based regulation, according to which 90% of the places are reserved for Bumiputeras . Another criticism is that the program is less demanding than participating in the STPM and that it gives Bumiputeras easier access to university places overall. The critics see matriculation as a modified form of the earlier racial discrimination, in which university access was directly linked to a quota system.

The "Center for Basic Science Research" at Universiti Malaya offers two programs exclusively for Bumiputeras:

- The "Science Program", a one-year course of the Ministry of Higher Education. After completing this program, the students will be placed on various science-based courses at the universities of the country according to their performance.

- A special preparatory program that serves as college entrance for Japanese universities. The two-year intensive course is organized by the Office of Public Administration in cooperation with the Japanese government.

Some of the graduates take preparatory courses in private colleges. There are several programs to choose from, such as the UK A-Level Program, the Canadian Enrollment Program, the Australian NSW Board of Studies Higher School Certificate and the American High School Diploma . The International Baccalaureate has recently been enjoying increasing popularity as a qualification program.

The official announcement by the Malaysian government is that access to universities is all regulated according to meritocratic principles . Due to the large number of preparatory courses and without comparison criteria between the individual programs, the Malaysian public is skeptical about these statements.

Tertiary level

In 2004 the government created the Ministry of Higher Education to specifically oversee the tertiary education sector. The ministry is headed by Mustapa Mohamed . The classification levels of tertiary education are based on the Malaysian Qualifications Framework (MQF) published by the ministry . The aim of the MQF is a uniform system of qualifications that apply at the national level to both the vocational and academic sectors.

Prior to the introduction of the Malaysian enrollment system, applicants to public universities were required to complete an additional 18 months of Form 6 secondary school and take the STPM final exam ( Sijil Tinggi Persekolahan Malaysia or Malaysian Higher School Certificate ). Since the introduction of the matriculation program in 1999 as an alternative to the STPM, it has been possible to gain access to universities within Malaysia by participating in a 12-month course run by special matriculation colleges ( kolej matrikulasi ). However, only 10% of the places in these courses are given to non-bumiputeras.

Prior to 2004, a postgraduate degree was a prerequisite for all university professors . In October 2004 this requirement was dropped and the responsible ministry announced that "experts from industry who can make a significant contribution to a lecture" can apply directly for the position of university lecturer even without postgraduate qualifications. To counter suspicions that there is a shortage of teaching staff at the universities, said Deputy Minister of Education Datuk Fu Ah Kiow

“This is not because we are facing a shortage of lecturers, but because this move will add value to our courses and enhance the name of our universities ... Let's say Bill Gates and Steven Spielberg, both [undergraduates but] well known and outstanding in their fields, want to be teaching professors. Of course, we would be more than happy to take them in. "

As a further example, he cited the architecture course, in which architects who are known for their talent hold lectures without a master's degree.

Students can also enroll in private institutions. Private universities can increasingly boast a reputation for internationally qualified courses and students from all over the world. Many of them have collaborative agreements with foreign institutes and universities, especially in the United States, Great Britain and Australia, where students can spend semesters abroad and gain experience abroad. One example is SEGi University College , which partners with the University of Abertay Dundee . The so-called "twinning" is popular, with part of the course being completed in Malaysia and part at the partner institution. With "full twinning" all grades and course certificates are fully transferable. Some private universities are branches of foreign institutions.

Since 1998, several internationally renowned universities have established a "branch campus" within Malaysia. Such a branch campus offers the same courses and degrees as the main campus. Both Malaysian and international students can thus obtain degrees from their respective institutions at significantly lower tuition fees. The following universities and institutions maintain a branch campus in Malaysia:

- Monash University Malaysia Campus

- Curtin University of Technology Sarawak Campus

- Swinburne University of Technology Sarawak Campus

- University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus .

- SAE Institute , Australia

- Raffles Design Institute , Singapore

Prime Minister Mahathir bin Mohamad countered the brain drain in 1995 with his brain gain program . This program aimed to attract 5,000 skilled workers annually. In a parliamentary question in 2004, the Minister of Science, Technology and Innovation, Datuk Jamaluddin Jarjis , stated that in the years 1995 to 2000, 94 scientists (including 24 Malaysians) from the fields of pharmacology, medicine, semiconductor technology and engineering from the program will be supported by the program Had come abroad. At the time of the parliamentary question, however, only one of them was still working in Malaysia.

Postgraduate studies

Postgraduate degrees such as the Master of Business Administration (MBA) and Doctor of Business Administration (DBA) are enjoying increasing popularity and are on the curriculum in both universities and private colleges .

The Master of Science can be obtained through specialist work or research at all public and some private higher education institutions. The Doctor of Philosophy is awarded there exclusively on the basis of research.

Vocational and polytechnic schools

In addition to a university degree, there is also the option of taking courses at vocational schools such as B. the ICSA (Institute of Chartered Secretaries and Administrators). Training at a Malaysian polytechnic leads to a certificate level after two years and a diploma level after three years .

The following list summarizes the polytechnic colleges in Malaysia:

- Politeknik Ungku Omar - Premier Polytechnic (University Status)

- Politeknik Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah

- Politeknik Sultan Abdul Halim Muadzam Shah

- Politeknik Kota Bharu

- Politeknik Kuching Sarawak

- Politeknik Port Dickson

- Politeknik Kota Kinabalu

- Politeknik Sultan Salahuddin Abdul Aziz Shah - Premier Polytechnic (University Status)

- Politeknik Ibrahim Sultan - Premier Polytechnic (University Status)

- Politeknik Seberang Perai

- Politeknik Kota, Melaka

- Politeknik Kota, Kuala Terengganu

- Politeknik Sultan Mizan Zainal Abidin

- Politeknik Merlimau

- Politeknik Sultan Azlan Shah

- Politeknik Tuanku Sultanah Bahiyah

- Politeknik Sultan Idris Shah

- Politeknik Tuanku Syed Sirajuddin

- Politeknik Muadzam Shah

- Politeknik Mukah

About 150,000 qualified graduates come from Malaysia's universities each year.

Other types of schools

In addition to the public schools, there are other types of schools in Malaysia.

Islamic religious schools

Malaysia has its own system of Islamic religious schools. The primary level is called Sekolah Rendah Agama (SRA), while the secondary level is called Sekolah Menengah Agama (SMA).

Another type of school is the Sekolah Agama Rakyat (SAR). These schools teach Muslim students about Islam-specific topics such as Islamic history , Arabic and Fiqh . Although some states, such as Johor, require all Muslims between the ages of six and twelve to attend these schools, attendance at these schools is not compulsory. The last school year of these schools ends with a final exam. Most SARs are financed by the respective federal states and also supervised by their religious authorities.

Former Prime Minister Tun Mahathir Mohammad suggested closing the SAR and integrating the teaching content into the public schools. However, this request met with many opponents and the proposal disappeared again into oblivion.

Although these schools still exist in Malaysia, they hardly play a role in the big cities. In rural areas, however, this type of school is still popular. The major universities in the country accept degrees from some of these schools for courses leading to the Malaysia High Certificate of Religious Study (Sijil Tinggi Agama Malaysia, STAM for short) . Most religious-only graduates, however, begin studying in Pakistan or Egypt. Among the graduates there are well-known personalities such as Nik Adli, the son of the PAS chairman Nik Aziz.

Some parents also send their children to special religious events outside of school, such as Dharma classes , Sunday schools, or Koran classes in mosques after regular school lessons .

Private schools

International schools

In addition to the national curriculum, Malaysia has many international schools. These offer students the opportunity to study according to another country's curriculum. The international schools are mainly aimed at the growing number of expatriates in the country. The list of international schools includes:

- Fairview International School

- REAL Schools (British curriculum),

- Melaka International School (UK curriculum),

- Australian International School (Australian curriculum),

- Alice Smith School (British curriculum),

- elc International school (British curriculum),

- Garden International School (UK curriculum),

- Lodge International School (UK curriculum),

- International School of Kuala Lumpur (International Baccalaureate and American curriculum),

- Mont 'Kiara International School (International Baccalaureate and American curriculum),

- Japanese School of Kuala Lumpur (Japanese curriculum),

- Chinese Taipei School, Kuala Lumpur (Taiwanese Curriculum),

- Chinese Taipei School, Penang (Taiwanese Curriculum),

- International School of Penang (International Baccalaureate and British curriculum),

- Dalat International School in Penang (American curriculum),

- Prince of Wales Island International School in Penang (British curriculum),

- Lycée Français de Kuala Lumpur (French curriculum),

- Horizon International Turkish School (Turkish curriculum),

School uniforms

School uniforms ( pakaian seragam sekolah ) in the western style adapted from Malaysia in the late 19th century during the British colonial era. Today school uniforms are ubiquitous in both public and private schools. From January 1, 1970, school uniforms became compulsory in all schools in Malaysia.

A typical form of the school uniform is that of the public schools. The dress code for boys is largely standardized, while the school uniforms for girls can differ significantly depending on religion and type of school. Boys wear a collared shirt and shorts or long trousers. Girls wear a knee-length pinafore dress and a shirt with a collar, a knee-length skirt and a shirt with a collar or the baju kurung , which is mandatory for Muslim schoolgirls and consists of a top and a long skirt and optionally the hijab (tudung) . White socks and black or white shoes are also mandatory, while ties are only required by some schools. Class representatives and students with special functions occasionally wear uniforms of different colors; different colors may also be used between primary and secondary schools.

Educational policy

Education policy is represented by the Ministry of Education . In July 2006, the Deputy Minister of the Ministry of Higher Education , Datuk Ong Tee Keat, announced that the controversial Universities and University Colleges Act (UUCA) would be subject to parliamentary review. The governing coalition is made up of a wide variety of ethnic groups and one of the concessions that the majority of the Malays represented there were willing to make was the possibility for the Chinese and Indians to open their own universities.

National Education Blueprint

In 2006 the National Education Blueprint 2006-10 was published. The paper listed a number of goals including

- the establishment of a national pre-school curriculum ,

- the creation of one hundred special school classes,

- the increase in the proportion of single-session schools to 90% for primary schools and 70% for secondary schools and

- the reduction in classes from 31 to 30 students in primary schools and from 32 to 30 in secondary schools

by 2010. The blueprint also exposed a number of weaknesses in education policy. According to this, 10% of the primary schools and 1.4% of the secondary schools do not have a continuous power supply, 20% and 3.4% are not connected to the public water supply and 78% and 42% of the schools are older than 30 years and need renovation . The report found that 4.4% of primary school students and 0.8% of secondary school students in the "3M" were not powerful. The failure rate for the transition to secondary school was 9.3% in urban and 16.7% in rural areas.

The blueprint also addressed issues of racial polarization in schools. As suggested solutions, the paper named seminars on the Malaysian constitution, motivation camps to promote cultural awareness, culinary focus weeks that highlight the different cooking styles of the ethnic groups and writing competitions about the different traditions. Mandarin and Tamil lessons are to be offered in the national schools from 2007 as part of a pilot project.

The blueprint drew some criticism. Scientist Khoo Kay Kim said:

“We do not need this blueprint to produce excellent students. What we need is a revival of the old education system ... meaning the education system we had before 1957. That was when we saw dedication from the teachers. The Malaysian education system then was second to none in Asia. We did not have sports schools but we produced citizens who were Asian class, if not world class. "

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ Puthucheary, Mavis (1978). The Politics of Administration: The Malaysian Experience , p. 9. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-580387-6 .

- ↑ Puthucheary, pp. 9-10.

- ↑ Puthucheary, p. 10.

- ↑ Puthucheary, pp. 10-11.

- ^ Primary School Education . Malaysia.gov.my. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ↑ Shazwan Mustafa: Malay groups want vernacular schools abolished . The Malaysian Insider. August 22, 2010. Archived from the original on August 25, 2010. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- ^ English in Schools: Policy reversed but English hours extended , New Straits Times , July 9, 2009.

- ↑ Beech, Hannah (October 30, 2006). Not the Retiring Type (page three). TIME .

- ↑ Liz Gooch: In Malaysia, English Ban Raises Fears for Future - NYTimes.com , NYTimes . July 10, 2009. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- ^ Matriculation Program , From the official website of Ministry of Education, Malaysia. Accessed August 9, 2011.

- ^ Academic Qualification Equivalence . In: StudyMalaysia.com . Retrieved September 15, 2010.

- ↑ Swee-Hock Saw , K. Kesavapany : Malaysia: recent trends and challenges . Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore 2006, ISBN 981-230-339-1 , p. 259.

- ^ University Partners: University of Abertay Dundee, UK . SEGi University College . Archived from the original on May 24, 2010. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ↑ Foreigners in Malaysia Prefer Turkish Schools . Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ↑ theSun ( Memento of the original from July 9, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Koh, Lay Chin in: New Straits Times Free hand for 'clusters' to excel , p. 12, January 17, 2007

- ^ New Straits Times: Enhancing racial unity in national schools , p. 13, Jan. 17, 2007

- ^ "Review of curricula soon", p. 13th (January 17, 2006). New Straits Times .

- "Country Facts - Malaysia" . Accessed October 16, 2005.

- "A Glimpse of History" . Accessed October 16, 2005.

- "PM Unveils Caring Budget, More New Measures To Perk Up Economy" . (September 30, 2005). Bernama .

- Yusop, Husna (October 16, 2005). Speaking of culture . The Sun .

- Yusop, Husna (March 9, 2006). Time to overhaul education system . Malaysia Today .

- Tan, Peter KW (2005), 'The medium-of-instruction debate in Malaysia: English as a Malaysian language?', Problems & Language Planning 29: 1, pp. 47-66 The medium-of-instruction debate in Malaysia

Remarks

- ↑ Translation: In short, the Malaysian boy is told "You were raised to be at the bottom and you have to stay there forever!" Why, I ask, waste so much money to achieve this, when this Malaysian boy can accomplish this achievement all by himself, without school and without effort?

- ↑ The STPM is equivalent to the British " General Certificate of Education A Level" or, at international level, the Higher School Certificate .

- ↑ Translation: It's not because we have too few university teachers, but this move will enrich our courses and improve the reputation of our universities. Let's say that Bill Gates and Steven Spielberg, both without degrees but well known and outstanding in their fields, wanted to give lectures. Of course we would be more than happy if we could have them with us.

- ↑ The single-session school is a kind of all-day school with classes for all students from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. on 5 school days per week. It is in contrast to the traditional double-session school, where some of the students are taught in the morning and some in the afternoon on 6 school days per week.

- ↑ 3M in Malaysia stands for membaca, menulis, mengira , i.e. reading, writing, arithmetic

Web links

- Universities and Colleges in Malaysia

- Ministry of Education official website

- Ministry of Higher Education official website

- Education Malaysia , website of the Malaysian government promoting the Malaysian educational model.

- United Chinese School Committees Association of Malaysia (UCSCAM) , also known as "Dong Jiao Zong (董 教 总)"

- UNESCO Regional Office for Education in Asia report - The Educational Statistics System of Malaysia 1972 (PDF file; 7.90 MB)