Brancacci Chapel (Florence)

The Brancacci Chapel is a side chapel in the Maria del Carmine church in Florence , Tuscany . It is sometimes referred to as the “ Sistine Chapel of the Early Renaissance ” because of its cycle of paintings, which was one of the best known and most influential of its time .

history

The construction of the chapel in the Church of the Carmelites was commissioned by Pietro Brancacci and started in 1386. The frescoes were commissioned by the seafaring silk merchant Felice Brancacci , nephew and heir of Pietro, who had served the Caliph in Cairo as Florentine ambassador until 1423 . On his return to Florence he commissioned Masolino da Panicale to paint the chapel for the glory and salvation of his family. The pictures were supposed to show scenes from the life of St. Peter , the namesake of his uncle Pietro.

Felice's public standing in Florence was shattered when he embarked on a plot against the powerful Medici family . He had to go into exile , was convicted in absentia in 1435 and posthumously declared an enemy of the state in 1458. This had consequences for the chapel: the fresco of the martyrdom of St. Peter has been removed and in another fresco, The Awakening of Theophilus' Son, members of the Brancacci family have been painted over. Work could only be resumed and completed after 1480.

A first restoration is documented as early as the 16th century , as the frescoes had become dark due to the candle soot. In 1670 some statues were also erected. A century later, more pictures fell victim to the changed understanding of art: all frescoes in the top register were knocked off. It is possible that Adam and Eve , who had been naked until then , were provided with fig leaves during these measures .

During a fire in 1771 the chapel and with it the frescoes remained almost intact, apart from slight changes in color in some places due to the heat. In the 18th century the dome was painted with frescoes. At the beginning of the 20th century, restorers had to paint the walls of the chapel with a mixture containing eggs and casein to protect the paintings . Decades later, this layer began to peel off in places and take away paint particles, especially on the colder, more humid outer wall, where salt efflorescence and mold stains also spread. Therefore, extensive restoration work was required from 1984 onwards. It was found that the painters had painted not only on damp, but also in some places on dry plaster ( secco ) - for example on the sky blue and the cloak of the Apostle Peter. It was also shown that the same landscape was carried on from one scene to the next behind a pillar painted in a corner of the chapel .

The painters

Masolino's assistant was 21-year-old Masaccio , who was 18 years younger than Masolino. The two worked according to a uniform concept, which shows, among other things, the overarching landscape in the pictures next to the window, the coordinated sequence of the pictures or the apostle's always yellow coat.

Even before the frescoes were finished, Masolino went to Hungary to work there on behalf of the military leader Philippo Scolari , a Florentine in the service of Emperor Sigismund , so that Masaccio continued the work in the chapel alone. Most of the frescoes in the chapel are therefore from his hand. In his frescoes, Masaccio makes a radical break with the medieval pictorial tradition through his implementation of the then new perspective of the Renaissance . Perspective and light create deep spaces, his figures clearly show individual traits. Masaccio thus continues Giotto's path of breaking away from a symbolic view of the human being and painting realistically.

After Masolino's return to Florence he was called to Rome by Pope Martin V , where Masaccio followed him a short time later, so that the chapel remained unfinished. Masaccio died in Rome under unknown circumstances at the age of only 27. It is uncertain whether he was buried in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine. The fresco cycle there was only completed by Filippino Lippi from 1480 to 1485 while maintaining the pictorial program.

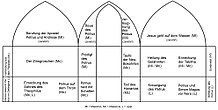

The frescoes

The Fall of Man (Masolino)

It is no coincidence that the cycle of images begins at the top right with a representation of the Fall . This scene and the opposite expulsion from Paradise are therefore the prerequisites for the other scenes, which show how Jesus Christ reconciles people with God.

Adam and Eve stand side by side in the fresco; their bodies seem a little elongated. They look at each other with determined eyes and are about to eat the forbidden fruit. Masolino shows Eva's connection to the tempter by letting her put her left arm around the slender tree, around which the snake winds in opposite directions. This is shown with a human, blond-haired head. The picture is still very much influenced by the Gothic . This is evidenced by the soft lines, the unsteady posture of the people without a clearly recognizable background and the representation that does not extend very deep. Emotions are only expressed to a limited extent, e.g. B. Adam's hand position and looks.

Expulsion from Paradise (Masaccio)

Masaccio's work on the opposite page is famous for its liveliness and the expression of emotions that was unprecedented in painting. It stands in stark contrast to Masolino's more decorative image of the Fall. The dramatic scene shows an armed angel driving Adam and Eve from paradise. The two main characters are depicted in deep despair, the angel hovering above them shows them with threatening sword drawn and pointing finger out of the Garden of Eden. Black divine rays shoot out of the paradise gate and emphasize the dynamism. Adam covers his face in despair and guilt; Eva shamefully covers her nakedness and screams with a pained face. The painter also strives for realism in details: Adam and Eve stand firmly on the floor, their bodies casting shadows. Eva's arm position corresponds to that of Venus Pudica . In the meantime, the genitals had been painted over with leaves, but this was removed again during the last restoration in 1990.

Calling Peter (Masolino)

In the lunette at the top on the left, Masolino had painted the scene in which Jesus at the Sea of Galilee calls Simon Peter and his brother Andrew to follow him (among other things, Lk 5.1-11 EU ). The picture was destroyed between 1746 and 1748 and is only known thanks to some references from earlier witnesses such as Giorgio Vasari and Filippo Baldinucci .

The overall arrangement of the pictures in the chapel was planned: in the vault a representation of the sky, in the top register images of the sea, in the registers below earth events. The pictorial program thus follows the sequence shown in the biblical creation story at the beginning of the book of Genesis: first the sky, then the water, and finally the land.

The walk on the water (Masolino or Masaccio)

A lost fresco on the opposite side corresponded to the appointment scene. Here, too, Jesus and Peter were the main characters. The picture showed Jesus walking on the water. Mt 14,22-33 EU . Most sources attribute this fresco, which was destroyed in the 18th century, to Masolino, while others vote for Masaccio.

Betrayal and repentance of Peter

Two other frescoes no longer exist, which were to the right and left of the current window. The right one depicts Peter, as he denied three times after the arrest of Jesus and his later repentance, which the left fresco depicts Joh 18,17ff EU , Lk 22,62 EU . A very schematic preliminary drawing has been preserved from this, but it does not allow any clear conclusion as to whether the frescoes are by Masolino or Masaccio.

The interest penny (Masaccio)

Healing of the paralyzed and awakening of the Tabitha (Masolino / Masaccio)

The double scene in the upper picture on the right wall shows in the background a typical Tuscan town of the 15th century in central perspective, which is generally attributed to Masaccio. The two figures in the middle, which act as a link between the two scenes, show Gothic influences in their elegant, courtly appearance .

In the left half an event from the book of Acts is described ( Acts 3,1-10 EU ): The healing of the paralyzed man in the temple by St. Peter. In the picture, the eye contact between Peter and the paralyzed man is particularly emphasized.

In the right half of the picture you can see the awakening of Tabitha . More than 100 years earlier, Giotto had painted a fresco in Santa Croce on a similar subject , which Masolino certainly knew. Tabitha is a follower of Jesus from the city of Joppa on the Mediterranean Sea and is known for her warmth and willingness to help ( Acts 9,36–41 EU ). During the time that Peter was working in the Joppa area, Tabitha fell ill and died. Peter, called from nearby Lydda, brings them back to life. Also worth mentioning are some details in the background of the picture. There you can see laundry hanging out in the windows of the building, a bird cage, neighbors chatting from window to window or a monkey kept as a pet.

Peter's sermon (Masolino)

In the field of view to the left of the window, Peter preaches with an expressive gesture in front of a group of people who show very different reactions: the great attention of the two veiled women on the right and in the middle contrasts with the weariness of the bearded man between them. To the right of Petrus, a girl has fallen asleep, while behind the bearded man only the fearfully wide eyes of another woman can be seen. The faces behind Peter are probably portraits of contemporaries, as are those of the two monks on the right, attributed to Masaccio. The mountains are continued to the right of the window in Masaccio's picture.

Baptism of the new converts (Masaccio)

This picture of Masaccio shows a remarkable realism in a number of details: the water dripping from the hair of the newly baptized, the freezing of the waiting person to be baptized or the undressing of the next in line. Masaccio worked very much with complementary colors in this fresco , which was later taken up by Michelangelo , among others .

Peter heals with his shadow (Masaccio)

The background to this picture is Acts 5:15 EU , where it is reported that the sick were carried into the street so that at least the shadow of Peter may fall on them and heal them. The perfect perspective of the medieval houses - the front house with its surrounding bench and the rustic masonry on the ground floor is already built in the typical Florentine style of the Renaissance as well as the church facade with antique columns, gables and campaniles in the background - shows the fresco as work Masaccios out. The lifelike depiction of the old man and the paralyzed fits in with this. The dynamism of the sick is remarkable: the one in front is still paralyzed on the floor, the old man in the middle stands up straight, the bearded man next to whom Peter has already passed with his shadow, stands on his own two feet and thanks the saint with emotion with folded hands. There are also some portraits in this picture: The apostle John walking behind Peter supposedly shows the features of Masaccio's brother Giovanni, while the old bearded man in the background is said to represent the Florentine sculptor Donatello .

Distribution of the goods and death of Ananias (Masaccio)

According to the report of the Bible, community of property prevails in the early church: the rich sell their property, give the money to the apostles, who in turn distribute it to the needy. According to Acts 5 : 1–11 EU , however, Ananias and Saphira try to keep part of the sales proceeds for themselves. Peter reprimands this behavior and Ananias dies. The fresco shows this scene. The people involved - behind Peter the apostle John, in front of him presumably a widow with a child and a disabled person who are currently receiving money from Peter - stand in a semicircle around the dead Ananias and thus involve the viewer in the action.

Awakening of the son of Theophilus and Peter to the throne (Masaccio and Lippi)

The fresco records an event that is told in the Legenda Aurea , which was very popular in the Middle Ages . After his release from prison, Peter comes to Antioch , where, according to legend , he becomes a bishop . There, with God's help, he awakens the son of the regent Theophilus, who had died 14 years earlier. Out of gratitude, Theophilus converted to Christianity, had a church built and Peter was highly venerated.

In the fresco there are allusions to political events of the time. Specifically, it is about the conflict between Florence and the Duchy of Milan . Theophilus, sitting on his throne on the left, resembles one of the former main opponents of Florence, Gian Galeazzo Visconti . The sitter to the right of Theophilus is generally interpreted as the then Florentine Chancellor Coluccio Salutati , who then saved his hometown from the conquest of Milan. Memories of this threat were awakened when Florence came into conflict with Gian Galeazzo's son, Filippo Maria Visconti , before the painting was made. The central role of St. Peter in this fresco could symbolize the mediating role of the church in the person of Pope Martin V.

The four passers-by on the right edge of the picture can be Masaccio himself (he looks at the viewer from the picture), Masolino (the smallest), the writer and builder Leon Battista Alberti (in the foreground) and Filippo Brunelleschi (far right). The frequent embedding of portraits in pictures at the time allowed the imaginary world of painting and the viewer's personal world to converge. This picture by Masaccio was completed by Lippi decades later; the five figures on the left, the garments of the Carmelites and the hands of Peter on the throne come from this.

Paul visits Peter in prison (Lippi)

In Filippino Lippi's fresco, Peter stands behind the barred window of his prison cell ( Acts 12 : 1–19 EU ). His visitor, St. Paul , turn your back on the viewer. It is possible that Masaccio had already made a preliminary drawing for this picture, as the picture fits architecturally exactly to the picture on the right of the awakening of the son of Theophilus. He could not finish this picture as he was called to Rome in 1427, where he died a year later. In 1436 client Felice Brancacci was sent into exile because of his conflict with the Medici, so that a continuation of the work in the family chapel was out of the question. It is possible that some of the pictures that Masaccio had already completed were removed by opponents of the family because they showed portraits of members of the Brancacci family. Only after the return of this family to Florence in 1480 could work on the frescoes be resumed. Lippi stuck to the guidelines of his predecessors. The beginning of his work is not precisely documented, but thanks to some information from Giorgio Vasari, it can be dated to around 1485.

Liberation of St. Peter (Lippi)

The opposite picture follows on from the prison scene: It shows the liberation of St. Peter by an angel, while the guard armed with a sword sleeps leaning on a stick. The fresco is fully attributed to Lippi. Here, too, the painted architecture is adapted to the adjacent picture. It symbolizes the redemption of Christians - and possibly also the regained autonomy of the city of Florence after the Milan threat.

Peter and Simon Magus before Nero and the crucifixion of Peter (Lippi)

The scene of the double scene is possibly the Roman Porta Ostiensis ; on the left in the Aurelian wall you can see the Cestius pyramid . The fresco shows the emperor Nero sitting on the throne on the right , in front of him the apostles Peter and Paul and the heretic Simon Magus . A pagan idol lies at his feet . The background is the apocryphal Acts of Peter , which report how Simon, who is nicknamed "Magician", wields magic in the forum in front of the Roman Emperor Claudius, falls at Peter's prayer and is finally stoned by the crowd.

On the left you can see the crucifixion of Peter, which probably took place during the first persecution of Christians under Nero. The saint is upside down because he has not found himself worthy to be crucified in the same position as Christ. The painting contains numerous portraits: the young man looking out of the picture on the far right is Filippino Lippi himself. The old man in the red hat between Nero and Petrus represents the Florentine painter Antonio Pollaiuolo . The young man under the archway looking at the viewer is a portrait of Sandro Botticelli , Filippino's friend and teacher. In Simon Magus, some experts want to recognize the poet Dante Alighieri , who, among others, was very much appreciated by the Florentine ruler Lorenzo de Medici .

reception

Masaccio's use of precisely determined perspectives, the observance of a uniform direction of lighting, the skillful use of light-dark effects and the natural representation of people in different emotions justified a change in painting in Florence. The young Michelangelo was one of the many artists who received important inspiration from studying Masaccio's work in the chapel.

literature

- Umberto Baldini, Ornella Casazza: La Cappella Brancacci. Olivetti & Electa, Milan 1990.

- Umberto Baldini (Ed.): La Cappella Brancacci. La scienza per Masaccio, Masolino e Filippino Lippi. Olivetti, Milan 1992 (= Quaderni del restauro, 10).

- Luciano Berti (ed.): La Chiesa di Santa Maria del Carmine a Firenze. Giunti, Florence 1992.

- Alessandro Parronchi: Osservazioni sulla cappella Brancacci dopo il restauro, in: Commentari d'arte 2: 5 (1996), pp. 9-18.

- Diane Cole Ahl: Masaccio in the Brancacci Chapel, in: The Cambridge companion to Masaccio. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2002, pp. 138-157.

- Fabian Jonietz: The Scuole delle arti as places of aemulatio : The Fall of the Cappella Brancacci, in: Jan-Dirk Müller , Ulrich Pfisterer , Anna Kathrin Bleuler , Fabian Jonietz (eds.): Aemulatio. Cultures of competition in text and images (1450–1620) . De Gruyter, Berlin 2011 (= pluralization & authority, 27), ISBN 978-3-11-026230-8 , pp. 769-811.

- Elisa Del Carlo: La cappella Brancacci nella chiesa di Santa Maria del Carmine a Firenze. Mandragora, Florence 2012.

- Alessandro Salucci: Masaccio e la Cappella Brancacci. Polistampa, Florence 2014.

- Nicholas A. Eckstein: Painted Glories. The Brancacci Chapel in Renaissance Florence. Yale University Press, New Haven 2014.

- Nicholas A. Eckstein: Saint Peter, the Carmelites, and the Triumph of Anghiari: the changing context of the Brancacci Chapel in mid-fifteenth-century Florence, in: Studies on Florence and the Italian Renaissance in honor of FW Kent. Brepols, Turnhout 2016, pp. 317–337.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ B. Berenson, The Italian Painters Of The Renaissance, Pahidon (1952)

- ^ K. Shulman, Anatomy of a Restoration: The Brancacci Chapel , 1991, p. 6

- ^ A. Ladis, Masaccio: La Cappella Brancacci , 1994

- ↑ Article about the restoration in the mirror , issue 23, 1988

- ↑ Federico Zeri, Masaccio: Trinità, Rizzoli (1999), p. 28

- ↑ Klaus Zimmermann: Florenz, Ostfildern 2012, p. 289, ISBN 978-3-7701-3973-6

- ↑ John Spike, Masaccio, cit. (2002); Mario Carniani, La Cappella Brancacci a Santa Maria del Carmine, ibid., (1998)

- ↑ John Spike, Masaccio, Rizzoli, Milan (2002)

- ^ U. Procacci, Masaccio. La Capella Brancacci, Florence (1965), v. a. "Predica di san Pietro"

- ↑ Federico Zeri, Masaccio: Trinità , ibid., P. 32