Braunschweig faience

As Braunschweiger earthenware products are of two factories in Braunschweig referred, where from 1707 to 1807 faience were produced and utility ceramics. The older factory, the Ducal Manufactory, was located at the Alter Petritor , the second factory was near the turning gate .

history

Ducal Manufactory (1707–1807)

In 1707, Duke Anton Ulrich had given the order to build a princely faience factory, which produced ceramics under the name Braunschweiger Faience Factory (Delft-style porcelain factory) until 1807 . It was the first ceramic factory in the state of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel. The company initially produced mainly for the needs of the court at Salzdahlum Castle . The porcelain flower pots with the Duke's coat of arms mentioned there as early as 1697 were probably still obtained from the Netherlands, with the redesign of the park, more pots came from the Braunschweig factory. The company was managed by the Arnstadt glazier Johann Philipp Frantz (1668–1734), who, as a publisher (master) , was also responsible for operating the kiln . Other employees were his son as a glaze painter, a worker named Wilhelm Kannega (Caniga) for the potter's wheel and a ceramics former unknown by name. Frantz tried several times to take over the business as a tenant, but this failed. Frantz then worked as a porcelain painter for the Dorotheenthal manufactory near Arnstadt, which was later relocated to Augustenburg Castle.

However, since the manufacture did not generate much profit, it was leased to Heinrich Christoph von Horn in 1709 (the lease began on January 1, 1710 for six years) . The factory was located in the house of the potter Johann Andreas Pape, which was located on the Rennelberg between the city moat and the White Horse in front of the Petritor. In 1711, five workers and four apprentices were already working for Horn. However, he was unable to raise the rent due to debts that resulted from the unsuccessful earlier marketing of his goods, so that he added three more tenants by 1712. His cousin Werner Julius Günther von Hantelmann, who worked as a lawyer in Wolfenbüttel, was one of them. Despite everything, production and marketing went badly and von Horn withdrew from the loss-making business. On March 1, 1713, his cousins Heinrich Friedrich von Horn and Julius Dettmar Hagen were the tenants. But there was a dispute between them and in August 1714 Heinrich Friedrich von Horn was granted the sole right to call himself a “privileged independent faience manufacturer”. Due to modifications to the fortifications, he relocated the factory at his own expense to Beckenwerkerstraße at the corner of Kupfertwete. He got into debt after moving, but business was going well. However, the company suffered from the constant poaching of its qualified employees. After his death in 1731, his widow Sophie Elisabeth von Horn (née Wilmerding) ran the company. In 1735, a strict ban was imposed on the imitation of products from the manufactory, because in the meantime the manufacture of tiled stoves has started and the range of tableware has been expanded. Nevertheless, Sophie Elisabeth ran into economic difficulties in 1742 and had to sell the factory. The company then changed hands twice, first to the von Hantelmann brothers and then to Johann Erich Behling and Johann Heinrich Reichard in 1745, until in 1756 it was again in the hands of Duke Charles for a few years . In 1773 the company was leased from Benjamin Rabe, who bought it in 1776. In 1807 the faience factory was finally shut down.

Chelysche Manufactory (1745–1757)

| City map by FW Culemann from 1798 with the approximate location of the factories. |

|

|

In contrast to the princely establishment of a porcelain manufactory , the "Porcellain und Dutch Tobacco Pipe Fabric" founded by Rudolph Anton Chely from June 1745, was called the "Porcellainfabrik vor dem Wendentore" to distinguish it from the Hornschen factory in Beckenwerkerstraße because it was Chely's house near the turnaround gate, a private company. Chely was a captain in the Brunswick army and was given the privilege of producing "real and fake porcelain on white and blue and all other colors of painted glazes" on his property for ten years. He had previously trained his son Christoph Rudolph in Strasbourg in the processing of muffle inks and then took over the business. As with the other manufacturers, the privilege included an exemption from taxes on his house, permission to dig freely for sand and clay , exemption from export duties on his goods, permission to sell anywhere and anytime, and a shop ( boutique ) at a preferential price to set up. The wish to have his two sons share in the lease was not granted. Between 1747 and 1749, the factory employed 20 people, seven of whom were soldiers. In November 1749, Chely apparently had trouble with the Brunswick city council and was placed under arrest for several years. However, no details have been handed down about this process. Though business was not going well, Chely applied for an extension of the privilege on November 28, 1754, well in advance of the deadline. On June 3, 1755, he reported to the ducal chamber that business was bad. In his letter, for the first time, he no longer describes his goods as fake porcelain , but instead uses the term faience . His son took over the manufacture for a short time. Finally it was closed in 1757. Chely's porcelain brand with the two intertwined Cs can easily be confused with the brands of the Ludwigsburg porcelain factory and the Niederweiler factory , which have a similar signet. If the products from Niederweiler and Ludwigsburg are carefully painted on the glaze, Chely's products are simpler and less accurate. Blistering paint, cracked glazes and shards, an allegedly tinny sound when knocking against it, and the fact that it is limited to northern Germany, suggest products of inferior quality from the Chely factory.

Privileges and busy glaze painters

Von Horn was the first to receive the privilege of a “perfect porcelain factory” in the hope that he could imitate the Dresden production made of red clay. With the takeover, Behling and Reichard received the privilege to manufacture everything that could be made from “porcelain” and red earth at their own expense. The privileges granted allowed the respective “porcelain factories” not only to produce faience, but also so-called real porcelain . The Braunschweig manufacturers, however, limited themselves to the production of faiences that were easier to produce.

One of the painters who worked in the Braunschweig factories in 1718 was Johann Kaspar Rib, also known as Johann Caspar Ripp (1681–1726), who on July 8, 1720 , asked Johann August von Anhalt-Zerbst for permission to set up his own factory . Other painters between 1745 and 1756 were Martin Friedrich Vielstich († 1752), father of the later Lesum faience manufacturer Johann Christoph Vielstich , Johann Vilgrab (also Fielgraf), Heinrich Jacob Behrens, Berend Adolf Meinburg, Johann Michael Tieling, Sebastian Heinrich Kirch (around 1711– 1768), Johann Thiele Ziegenbein, Ludwig Ferdinand Wilhelm Heuer and Johann Paul Abel.

Working conditions in the factories

Using the example of the von Horn manufactory, which has been privately operated since the lease, but was still called Princely Porcellain-fabric , the primitive and improvisational working conditions in the manufactory can be well described. After the invention of European porcelain by Johann Friedrich Böttger , the Braunschweig ceramists wanted to manufacture this as well from 1707. But the operational conditions were poor. The kiln was too small to be able to work economically, which resulted in a high consumption of firewood. There was no adequate storage space for the sensitive raw material, the basement masonry containing nitric oxide and the unpaved basement floor led to contamination of the rough material , so that the glaze paints painted on fell off during the fire.

It was only possible to work in the warm season, as there was a risk that the clay could freeze in winter. In summer, on the other hand, the lack of thermal insulation in the so-called lathe rooms was uncomfortably noticeable because the workpieces turned on the pottery wheels, especially those for dishes, dried out too quickly and led to deformations. Even the glaze mill, which was too small, did not seem to have been technically well designed. The upper millstone, the runner , was too light, making the grist too coarse-grained and unproductive. The kilns had no chimneys, so there was an increased risk of fire. In addition, there was no room to store the firewood. The financial means were lacking to remedy these disadvantages. This led to disputes between the operations manager Johann Philipp Frantz and the tenant Heinrich Christoph von Horn. Frantz then tried to open his own factory in Einbeck in 1711 , but was turned away and then his trace is lost in Braunschweig. Later it turned out that he (and other specialists in the manufactory) had probably been poached at the instigation of Duchess Auguste Dorothea Eleonore , a sister of the Duke, and found a new job in the Arnstadt porcelain factory at Augustenburg Castle.

Raw materials, products and labeling

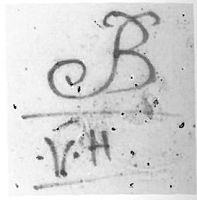

| connected initials VH Heinrich Christoph von Horn |

VH with B for Braunschweig |

tangled C s Rudolph Anton Chely |

The clay used for production from the geological period of the Lower Cretaceous came from Lutter am Barenberge and Oberg , while the other ingredients had to be procured outside of the duchy. The Braunschweig pottery companies also processed different clays that came from the Mastbruch (near today's main cemetery) in the southeast of the city.

In the Braunschweig factories, utensils such as dishes, tiles and stove tiles were mostly made. Luxury goods such as vases and figurines were added later. Despite the lack of secure sales markets, Braunschweiger Keramik had a good reputation. It could adapt to all changes in style in the decor of the 18th century. Sometimes Meissner models were copied, like a pair of Egyptian sphinxes . The so-called wall blakers , a kind of candle holder, are considered to be particularly artistically valuable , showing ancient landscapes of ruins in a kind of framing rocaille ornamentation in so-called muffle colors , which are painted on the already glazed second fire.

On August 9, 1781, a “B” or “Br” was prescribed as a trademark for Braunschweig faiences. Previously, the brands, depending on the owner, were marked with a “V” based on “H” for “von Horn” or “von Hantelmann”, or “B” and “R” - the first letters of Behling and Reichard. Initially, the faiences were mainly decorated with shades of blue, later on they switched to multi-colored painting. Around 1750 shades of lively blue, dark manganese violet, lemon yellow, green and pale brick red were used.

Some pieces from the two factories are now in the Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum and the Städtisches Museum in Braunschweig. A special product by the Chely Manufactory from 1747 was in the former Berlin Palace Museum , probably until the Second World War . It was a porcelain barrel with a diameter of 51 cm and 72 cm in length. The barrel bottoms were decorated on the one hand with a depiction of Omphale with Heracles , on the other hand with a verse inscription that referred to the Duchess Christine Luise von Oettingen-Oettingen . The barrel filled with wine was apparently presented to the Duchess on her last birthday; she died in November of that year. It served as a promotional item but also to draw the farm's attention to Chely's business and thus to get orders.

Distribution of the goods

The pottery was mainly offered by peddlers . The privilege of Duke August Wilhelm from 1714 for the first Braunschweig manufactory, which was now leased from Heinrich Friedrich von Horn, also allowed free sale at all fairs, such as the Freyschießen fair on the Masch , fairs, markets and also in a modest one to set up a boutique , a retail shop.

Others

On January 11, 1747, Duke Karl also founded a porcelain factory in his hunting lodge in Fürstenberg on the Weser , which has been in operation for more than 250 years. In addition to a visitors' workshop, the castle houses a porcelain museum, the administration building and the manufacturing facilities. The company is one of the oldest still existing porcelain manufacturers in Europe.

See also

literature

- Luitgard Cramer: Faience manufacturers. In: Luitgard Camerer , Manfred Garzmann , Wolf-Dieter Schuegraf (eds.): Braunschweiger Stadtlexikon . Joh. Heinr. Meyer Verlag, Braunschweig 1992, ISBN 3-926701-14-5 , p. 70 .

- Siegfried Ducret: Unknown about the 2nd ducal faience factory in Braunschweig, 1756–1773. In: Keramos. 18. 1962, ISSN 0453-7580 , pp. 3-8.

- Hela Schandelmaier, Helga Hilschenz-Mlynek: Lower Saxony faiences. The Lower Saxony manufactories. Braunschweig I and II, Hannoversch Münden, Wrisbergholzen. Kestner Museum, Hanover 1993, ISBN 3-924029-20-2 .

- Christian Scherer : The Faience Factory [sic!] In Braunschweig. In: Braunschweigisches Magazin. Edited by Paul Zimmermann, No. 6, March 15, 1896, pp. 41–45.

- Christian Scherer: The Chelysche faience factory in Braunschweig. In: Festschrift for Paul Zimmermann on the completion of his 60th year of life by friends, admirers and employees (= sources and research on Braunschweigischen history. Volume 6), Wolfenbüttel 1914, pp. 269–280.

- Christian Scherer, Braunschweig Municipal Museum: Braunschweiger faiences. Directory of the Braunschweig faience collection in the Braunschweig Municipal Museum. Appelhans, Braunschweig 1929, ( tu-braunschweig.de ).

- Gerd Spies : Braunschweig faience. Klinkhardt & Biermann, Braunschweig 1971, OCLC 325850 .

- Gerd Spies: News about Braunschweig faience. In: Weltkunst. No. 8/1973, ISSN 0043-261X , pp. 602-603.

- Gerd Spies: Braunschweig faience. In: Weltkunst. No. 48/1978, ISSN 0043-261X , pp. 704-705.

- August Stoehr: German faience and German earthenware. A guide for collectors and enthusiasts. Richard Carl Schmidt & Co, Berlin 1920, p. 337 ff. ( Dfg-viewer.de ).

Web links

- Faience potpour vase (around 1760) - Braunschweig faience factory. at tafelkultur.de

- Candlestick in the form of a bust of Caesars (Nero?) Made of faience. on Objektkatalog.gnm.de

- Restoration of a pug made by the Chely factory in Braunschweig. (PDF) at schloesser.bayern.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ City Chronicle Braunschweig. braunschweig.de, accessed on December 1, 2015 .

- ↑ Hela Schandelmaier, Helga Hilschenz-Mlynek: Lower Saxony faience. Hanover 1993, p. 324 f.

- ↑ Hela Schandelmaier, Helga Hilschenz-Mlynek: Lower Saxony faience. Hanover 1993, p. 31 ff.

- ↑ Sandy Alami: "Of Truly Artistic Execution". Porcelain plate painting from Thuringia since the 19th century. Waxmann Verlag, Münster 2014, ISBN 978-3-8309-8078-0 , p. 27. ( books.google.de )

- ^ Emil Ferdinand Vogel : Antiquities of the city and the state of Braunschweig. After mostly unused manuscripts and with illustrations. Frdr. Otto, Braunschweig 1841, OCLC 162367561 , p. 45 ( books.google.de )

- ↑ a b August Stoehr: German faience and German earthenware. A guide for collectors and enthusiasts. P. 338.

- ↑ a b August Stoehr: German faience and German earthenware. A guide for collectors and enthusiasts. P. 339.

- ↑ Victor-L. Siemers: Horn, Heinrich Christoph von. In: Horst-Rüdiger Jarck , Dieter Lent et al. (Ed.): Braunschweigisches Biographisches Lexikon - 8th to 18th century . Appelhans Verlag, Braunschweig 2006, ISBN 3-937664-46-7 , p. 359-360 .

- ↑ a b c Otto Riesebieter: The German faience of the 17th and 18th centuries. Klinkhardt & Biermann, Leipzig 1921, OCLC 1417897 , p. 250 ff. ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Christian Scherer: Braunschweiger Faience. Reprint 2013, ISBN 978-3-8460-9513-3 , pp. 25-26. ( books.google.de )

- ↑ Hela Schandelmaier, Helga Hilschenz-Mlynek: Lower Saxony faience. Hanover 1993, p. 41.

- ↑ Victor-L. Siemers: Chely (also Gelius, Cheli), Rudolph Anton. In: Horst-Rüdiger Jarck , Dieter Lent et al. (Ed.): Braunschweigisches Biographisches Lexikon - 8th to 18th century . Appelhans Verlag, Braunschweig 2006, ISBN 3-937664-46-7 , p. 139 .

- ^ Gordon Campbell: The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, ISBN 0-19-518948-5 , p. 151. ( books.google.de )

- ^ Christian Scherer: Braunschweiger Faience. Braunschweig 1929, p. 29.

- ↑ a b Guide through the Hamburg Museum for Arts and Crafts: At the same time a… Verlag des Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg 1894, p. 352-353 ( archive.org ).

- ↑ Johann Kaspar Rib. In: Mitteilungsblatt / Keramik-Freunde der Schweiz (= Revue des Amis suisses de la céramique = Rivista degli Amici svizzeri della ceramica) 1993, pp. 27-29 ( e-periodica.ch ).

- ↑ Johann Caspar Ripp - from the traveling painter in the faience to the blue painter in Meissen and to the "yard manufacturer" in Zerbst. ( Keramikfreunde-keramos.de PDF).

- ↑ Johann Kaspar Rib - 3.5. Meaning of ribs for Ansbach. In: Mitteilungsblatt / Ceramic Friends of Switzerland. Issue 107, 1993.

- ^ Siegfried Müller , Michael Reinbold: Oldenburg: cultural history of a historical landscape. State Museum for Art and Cultural History Oldenburg, Oldenburg 1998, p. 274.

- ↑ Gerd Spies: Braunschweiger Faience. Klinkhardt & Biermann, Braunschweig 1971, p. 14 ff., P. 20.

- ^ Peter Scholz: Archaeometric investigations on ceramics of the 9th - 17th centuries of the city excavation Braunschweig. ( medievalarchaeologie.de PDF, p. 31.)

- ^ Christian Scherer, Städtisches Museum Braunschweig: Braunschweiger Fayencen. Directory of the Braunschweig faience collection in the Braunschweig Municipal Museum. P. 5 ( tu-braunschweig.de ).

- ↑ Hela Schandelmaier, Helga Hilschenz-Mlynek: Lower Saxony faience. Hanover 1993, p. 24 f.

- ↑ The Princely Faience Manufactory. and The Faience Manufactory by Rudolph Anton Chely. In: Cecilie Hollberg , Städtisches Museum (ed.): "Congratulations, Carl!" Luxury from Braunschweig. Municipal Museum, Braunschweig 2013, ISBN 978-3-927288-35-5 . (Exhibition catalog).

- ^ Christian Scherer: Braunschweiger Faience. Braunschweig 1929, p. 30.

- ↑ Gerd Spies: Braunschweiger Faience. Braunschweig 1971, p. 18.

- ↑ Höxter in the Weser England: Porcelain Manufactory Fürstenberg. hoexter-tourismus.de, accessed on December 10, 2015 .