Brown v. Board of Education

| Brown v. Board of Education | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Negotiated December 9, 1952 / December 8, 1953 |

||||

| Decided May 17, 1954 |

||||

|

||||

| facts | ||||

| Parents class action lawsuit in the state of Kansas against mandatory segregation in state elementary schools | ||||

| decision | ||||

| Racial segregation in public schools is a violation of the principle of equality as specified in the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, as separate institutions are always unequal. | ||||

| occupation | ||||

|

||||

| Positions | ||||

|

||||

| Applied Law | ||||

| 14. Amendment to the Constitution | ||||

| reaction | ||||

|

Nationwide abolition of racial segregation in public schools, monitored by the federal courts of the relevant court district |

Brown v. Board of Education is the collective name for five cases before the Supreme Court of the United States from 1952 to 1954 on the subject of racial segregation in public schools . The class actions brought by concerned parents against four states and the federal district took the position that separate facilities for students separated by skin color violate the principle of equality of the United States Constitution. The Supreme Court unanimously endorsed this line of argument with its landmark judgment of May 17, 1954, thereby repealing the case law that had previously been in force for almost a hundred years. The decision marked the end of legally sanctioned racial segregation in state schools in the United States.

Historical background

Racial segregation has been a hotly debated issue in the United States since its inception in 1781. Even at that point there were significant differences and differences of opinion about the role that blacks should play in the new republic, who were brought into the former British colonies as slaves . The constitution of 1791 already contained a passage that forbade Congress to regulate the import of slaves before 1808. The federal structure of the political system allowed each state to decide for itself whether slavery should be allowed and which legal rules should be applied. The onset of industrialization in the northern states also meant that the need for slave labor there was significantly lower than in the labor-intensive, agricultural-based southern states. While immigrants from Europe could be found for industrial work, the south continued to rely on slaves.

In the Missouri Compromise in 1820, the states agreed in Congress that the number of slave-holding and slave-free states should remain the same. This was to prevent the slave question from becoming a political issue for the federal government. The result of the compromise equality of votes in the Senate ( Split Senate ) ensured that bills on slavery would not find a majority at the federal level.

The Supreme Court had not ruled on the slave issue until the mid-19th century. With the verdict in the Dred Scott v. Sandford of 1857 changed that with a decision that not only awarded the slave-owning states, but also denied Congress any authority to deal politically with the issue. The judges saw it as proven that it was fundamentally impossible for blacks to obtain American citizenship because they were a minor race and “are unable to associate themselves with the white race in political or social relationships”. The judges also declared that a ban on slavery was against the constitution because it constituted expropriation without the compensation provided for in the 5th Amendment . The verdict was of great political importance, as it shifted the laboriously negotiated balance in favor of the slave-holding states.

Shortly after the election of Abraham Lincoln in November 1860 came to the secession of several Southern states that did not support the political stance of the Northern states, fearing that the government would after the election increasingly work against slavery. The exit led to the Civil War , one of the bloodiest events in American history. After four years of warfare, the United States was able to assert itself against the separatists and reintegrated the states. The keeping of slavery and the unequal treatment of former slaves was forbidden at constitutional level with the adoption of the 13th (1865) and 14th amendments (1866); the Dred Scott judgment was thus also invalid.

The new political conditions did not last long, however. While more and more blacks were elected to political offices shortly after the end of the Civil War, the exhaustion of the federal government on this issue also led to a partial reversal of developments. After the end of the Reconstruction , when the federal troops had withdrawn from the southern states, the " Jim Crow Laws " were passed there, which were supposed to restrict the political and social possibilities of former slaves bypassing the constitutional changes. These laws were based on strict racial segregation . Public facilities such as hotels, schools, toilets, buses and trains, restaurants, sports facilities and clubs, hospitals and medical practices had to be separated according to legal requirements according to skin color.

These laws reached the Supreme Court in 1883 and 1896. In the judgments of 1883, known as civil rights cases, the court ruled that the constitutional amendments passed after the civil war did not grant the federal government the authority to take action against discrimination in private business relationships. In the case of Plessy v. Ferguson, the court specified his position and determined that legal racial segregation is generally allowed as long as there are separate but equal facilities for blacks and whites.

preparation

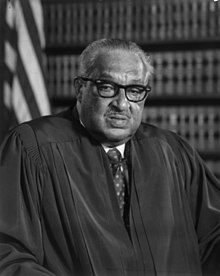

The case, which was heard by the Supreme Court in 1954, was based on a long-term strategy by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909 to improve the lives of all black Americans. As early as 1935, the organization tried to bring racial segregation to the courts through legal action. Thurgood Marshall , who was to be appointed the first African American Supreme Court Justice in 1967, devised a strategy to force negotiations through legal channels to accept black students at universities in the southern states. It was based on the fact that almost all universities in the southern states were previously reserved only for white students, while Afro-American school leavers mostly had no adequate access to a university education. This was intended to demonstrate the inadequacies of the “separate but equal” principle.

This strategy paid off for the first time in the Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada from. The state of Missouri was paying tuition fees for black students studying law in neighboring states at the time, but banned them from enrolling in its own universities. Here the judges ruled that such an approach was an inadmissible circumvention of Plessy v. Ferguson decision, because it did not provide any facilities for black students that would have to be the same.

In a subsequent case, the court ruled against the state of Texas , which rushed to set up a separate college to teach black students following a lawsuit seeking the admission of a black student to the state University of Texas . The court found that as Sweatt v. Painter known the case that the separate facility was completely inadequate and instructed the state to provide for a college with the same facilities as at the University of Texas or to accept black students there. The strategy also aimed at economic considerations by showing that completely identical facilities would only be possible through unbearably high costs at the expense of the taxpayer and that in the end it would be cheaper to accept black students in previously exclusively white schools.

The actual lawsuit, later known as Brown v. Board of Education came from Esther Brown , a white Jewish woman in Merriam, Kansas , a suburb of Kansas City, Missouri . Brown drove home her African-American housekeeper to see the dire state of the local school for blacks in the city of South Park, Kansas , while the city council was planning to issue new loans to build a school for whites. After a three-week joint boycott of the school, a branch of the NAACP successfully filed a lawsuit against the administration aimed at giving black students access to the new school.

legal action

After the success in South Park, Esther Brown tried to challenge racial segregation in the cities of Wichita and Topeka as well. In Topeka in particular, Brown found enthusiastic supporters in the local NAACP branch. After enough money was raised for the trial, the Topeka-NAACP attorney filed a lawsuit against the school district on February 28, 1951. The complaint was joined by 20 other families who were also affected by the legal racial segregation. The first plaintiff listed in the class action lawsuit was Oliver Brown , the case was resolved according to Oliver Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka called.

Oliver Brown testified during the interrogation that his nine-year-old daughter Linda Brown had to cross a busy street and the tracks of a neighboring industrial railway every morning in order to take the school bus to the black school one and a half kilometers away. In addition, there is a half-hour waiting time in front of the closed school, which has to be mastered even in rain and snow. At the same time, however, there is a school for whites only six blocks from Brown's house.

At the end of the hearing, the three judges unanimously found that the institutions were essentially equal, and noted in passing that the Supreme Court had never overturned "separate but equal", so the principle continued to apply. At the same time, the court stated that this separation harmed black school children and deprived them of the advantages of an integrated school.

At the time of the verdict, similar lawsuits were pending in three other states and the District of Columbia . The appeals in all five cases reached the Supreme Court together in 1952, with the first hearings taking place in December 1952. When Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson passed away, the trial was postponed for a year. Meanwhile, President Eisenhower appointed Earl Warren to the office. The next hearing took place in December 1953. Thurgood Marshall represented the plaintiffs at the hearing.

Judgments

Brown I

Earl Warren announced on May 17, 1954 the unanimous decision of the court that "separate educational institutions are inherently unequal". The court thus opposed the Plessy v. Ferguson judgment as well as against the judgment in the case of Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education from 1899, in which it had explicitly stated that separate educational institutions were not against the principle of equality of the constitution.

The reasoning for the judgment is comparatively short. For example, while Warren's important civil rights judgment, Miranda v. Arizona , taking up over 50 pages, Judge Warren managed here to concentrate the court's thoughts on eleven pages. However, it must also be borne in mind that the judgment separated the determination of the actual breach of the law from the determination of an appropriate legal remedy. With the pronouncement of the verdict, the court determines that racial segregation violated the constitution, but what consequences this has in detail for affected citizens should be decided in a subsequent hearing. Memories of the negotiations between the judges also show that this separation made it possible for Warren to obtain the unanimity of all judges, which was so important to him.

Warren chose an approach in his reasoning that was later criticized by many. Instead of dealing with the legal question of whether racial segregation in itself is against the constitution, Warren took a different route. His reasoning was based on social considerations, more precisely on the disadvantages that racial education institutions had for American society in general and black school children in particular. Warren asked whether the Equality Principle of Amendment 14 also included equal access to state educational institutions. In his remarks, Warren answered this question in the affirmative, referring to the incomparably great importance of education:

“Education is perhaps the most important task facing state and local governments today. Compulsory education laws and huge educational spending both demonstrate our understanding of the importance of education in a democratic society. It is required in the performance of our simplest public duties, even when serving in the military. It is the foundation of a good citizen. It is one of the main tools today to awaken children to cultural values, to prepare them for their future professional education and to help them adapt to their surroundings. It is now doubtful that a child can reasonably be expected to succeed in life when denied an education. Such an opportunity, if a state agrees to offer it, must be available to all on equal terms. "

The importance of education in public schools was emphasized because the judgment was based on the principle of equality in the 14th amendment to the US Constitution of 1868. If there had been state school systems separated according to origin as early as 1868, it would have been considered that the legislature did not want to question their admissibility. In 1868, however, private schools predominated, and black children generally do not attend schools at all.

In a separate judgment, the court ruled in the Bolling v. Sharpe that the constitutional principle of equality, which was actually aimed at the states, also applied to the federal government. This also made racial segregation unconstitutional for the federal capital Washington, DC and the other federal territories.

- Rubrum and implementation order of the court of May 17, 1954

Rubrum of judgment

Brown II

After the first judgment (Brown I) , a new hearing was scheduled for April 1955 to determine how the desegregation would be implemented. In the meantime, Judge Jackson passed away and President Eisenhower appointed John Marshall Harlan II to succeed Jackson. Harlan was the great-grandson of the judge of the same name, John Marshall Harlan , who was the only one in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson had voted against the majority and thus against racial segregation.

While the judges at Brown I were relatively easy to line up, Warren found himself confronted with major disagreements over exactly how racial segregation should be resolved. Judge Hugo Black was an advocate of repeal, but believed that it would be best if the Supreme Court said as little as possible about the actual solution to give the states their own discretion. Black and Judge William Douglas both believed that the court could not achieve anything in the short term and was dependent on the cooperation of the school districts concerned. Judge Felix Frankfurter took a contradicting position by speaking out in favor of a gradual transition to racial integration, but the way there should be determined by the court.

The judges finally agreed on a much-cited, often-criticized compromise: The states were instructed to push ahead with integration with “all deliberate speed” . The federal efforts should be monitored by the federal courts in the appropriate judicial district. Lawsuits against insufficient integration were possible, but not as class action . In order to force integration, lawsuits had to be filed separately in each school district if necessary. This was also intended to take account of the judges' fears that overly radical specifications by the court would meet with such increased rejection that they would ultimately be ignored.

consequences

Due to the way in which the judgments were designed, there was still a long way to go to end racial segregation after the decision had been announced, and this has not yet been completed in some cases. In many school districts, integration had to be sued through federal courts because the respective authorities either refused or postponed changes. In the state of Virginia , Senator Harry F. Byrd organized a resistance movement known as the Massive Resistance , which, among other things, included the closure of schools to prevent integration. In the state of Arkansas , Governor Orval Faubus ordered the National Guard to prevent black students, the Little Rock Nine , from entering Little Rock Central High School . President Eisenhower responded by mobilizing the 101st Airborne Division from Fort Campbell and assuming supreme command of the Arkansas National Guard.

An often used means of integration was the court order to distribute pupils of different skin colors with school buses in such a way that schools had a balanced proportion of pupils. This approach is based on the fact that in most states there is no free choice of school, so students are geographically assigned to specific school districts. As a result of the rulings, states began to draw the boundaries of these school districts in such a way that they remained separated by skin color as a result. A separation based on legal requirements became a practical separation based on school buses. In the 1970s, lawsuits against these proceedings increased, with the result that students sometimes attended schools dozens of kilometers away from where they lived. In 1971 the Supreme Court ruled in the Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education first found that integration forced by school buses was constitutional and an acceptable means of integration, but in part already revised this judgment in 1974 in the Milliken v. Bradley . Most court-imposed school bus programs were repealed during the 1990s.

criticism

The decisions of the Supreme Court were repeatedly criticized by lawyers. So wrote William Rehnquist , Chief Justice from 1986 to 2005, in a short note in 1952:

“I am aware that this is an unpopular and inhumanitarian opinion, for which I have been sharply criticized by“ liberal ”colleagues, but I think that Plessy v. Ferguson was correct and should be reconfirmed. ... In response to the argument ... that a majority should not deprive a minority of their constitutional rights, the answer must be that while this is theoretically reasonable, in the long run the majority will decide on the constitutional rights of the minority. "

Jurists, who are described as originalists and who attach great importance to the literal meaning of the constitution at the time of its adoption, were also critical of the judgment. Raoul Berger , professor of law at Harvard University , argued in his influential book Government by Judiciary that Brown v. Board of Education could not be defended given the original meaning of the 14th Amendment . This is already given by the fact that the Civil Rights Act of 1875 , passed shortly after the constitutional amendment, excluded schools from the institutions listed.

Today Brown is widely recognized as one of the landmark decisions of the 20th century. On the 50th anniversary of Brown I , President George W. Bush visited the Brown v. Memorial, which was opened in 1992 at the Monroe Elementary School . Board of Education National Historic Site in Topeka , Kansas, calling the verdict "a decision that forever changed America for the better."

literature

- Jeremy Atack and Peter Passell: A New Economic View of American History: From Colonial Times to 1940 . 2nd Edition. WW Norton & Company , New York 1994, ISBN 0-393-96315-2 .

- Edward L. Ayers : The Promise of the New South: Life after Reconstruction . Oxford University Press, New York 1993, ISBN 0-19-503756-1 ( [1] ).

- Jack M. Balkin: What Brown v. Board of Education Should Have Said . New York University Press, New York 2002, ISBN 0-8147-9890-X .

- Derrick A. Bell: Silent Covenants. Brown V. Board of Education and the Unfulfilled Hopes for Racial Reform . Oxford University Press, New York 2004, ISBN 0-19-517272-8 .

- Raoul Berger: Government by Judiciary: The Transformation of the Fourteenth Amendment . 2nd Edition. Liberty Fund, 1997, ISBN 0-86597-144-7 ( [2] ).

- John P. Jackson, Jr .: Science for Segregation: Race, Law, and the Case against Brown v. Board of Education. New York University Press, New York 2005, ISBN 978-0-8147-4271-6 .

- Richard Kluger: Simple Justice. A History of Brown v. Board of Education . Random House, New York 1977, ISBN 0-394-72255-8 .

- Daniel Moosbrugger: The American Civil Rights Movement . ibidem, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-89821-415-X .

- Charles J. Ogletree: All Deliberate Speed. Reflections on the First Half Century of Brown V. Board of Education . WW Norton & Company, New York 2004, ISBN 0-393-05897-2 .

- James T. Patterson Brown v. Board of Education: a civil rights milestone and its troubled legacy , Oxford University Press 2001

Web links

- Manfred Berg: Equal and Free , Die Zeit , No. 21, May 13, 2004.

- Special issue of the History of Education Quarterly (English) ( Memento from September 3, 2006 in the Internet Archive ).

- The Topeka Capital Journal Online: A Legacy Tour of the Brown Case .

- Interactive map showing Linda Brown's way to school, the “white” school and other places in Topeka that were significant for the Brown case .

- Brown Foundation , website (English).

- National Park Service: Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site. The Road to Justice (English).

Individual evidence

- ↑ cf. in New England the cases of Mum Bett and Quock Walker 1781-83 before the Federal Constitution was passed

- ↑ Article 5, United States Constitution.

- ^ Atack, p. 175.

-

↑ Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 US 393 (1957), p. 407:

“beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect ” - ↑ Ayers, p. 34

- ↑ Balkin, p. 29.

- ↑ 305 US 337 (1938)

- ↑ 339 US 629 (1950)

- ↑ Balkin, p. 30.

- ↑ Balkin, p. 32.

- ↑ 175 US 528 (1899)

- ↑ Balkin, p. 37.

-

↑ Judgment Brown v. Board of Education, 347 US 483 (1954), p. 493:

“Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments. Compulsory school attendance laws and the great expenditures for education both demonstrate our recognition of the importance of education to our democratic society. It is required in the performance of our most basic public responsibilities, even service in the armed forces. It is the very foundation of good citizenship. Today it is a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional training, and in helping him to adjust normally to his environment. In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms. " - ↑ 347 US 497 (1954)

- ↑ Balkin, p. 40.

- ↑ Balkin, p. 41.

- ↑ Craig Rains: Little Rock Central High 40th Anniversary. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on May 9, 2008 ; Retrieved August 11, 2007 .

- ↑ 402 US 1 (1971)

- ↑ 418 US 717 (1974)

- ^ Emily Yellin, David Firestone: By Court Order, Busing Ends Where It Began . In: The New York Times . September 11, 1999.

-

↑ The Surpeme Court, Expanding Civil Rights, Primary Sources. Thirteen / WNET, accessed August 11, 2007 . :

“I realize that it is an unpopular and unhumanitarian position, for which I have been excoriated by“ liberal ”colleagyes [sic], but I think Plessy v. Ferguson was right and should be re-affirmed. ... To the argument ... that a majority may not deprive a minority of its constitutional right, the answer must be made that while this is sound in theory, in the long run it is the majority who will determine what the constitutional rights of the minority are . ” - ↑ Berger, p. 132ff.

- ^ President Speaks at Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site