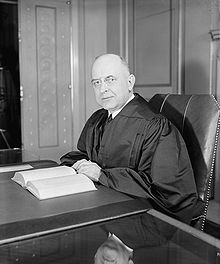

Stanley Forman Reed

Stanley Forman Reed (born December 31, 1884 in Minerva , Mason County , Kentucky , † April 2, 1980 in Huntington , New York ) was an American lawyer . He served as United States Solicitor General from March 1935 to January 1938 , during which time he represented the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt before the United States Supreme Court in several New Deal economic and social reform proceedings in response to the economic crisis that existed in the USA from 1929 and was known as the Great Depression had been resolved. He then worked until February 1957 as a judge at the Supreme Court. In the 19 years that he served at the court, he wrote more than 300 statements.

With regard to his positions on socio-economic issues, he was seen as predominantly progressive , but on certain social issues he also represented partially conservative views. During his tenure at the Supreme Court, in addition to the end of the New Deal in the early 1940s, the unanimous decision of Brown v. Board of Education on the desegregation of state schools in the United States, recognized as one of the most important landmark judgments in court history. At 95, he reached the highest age of any previous Supreme Court judge and was the last judge in the history of the court without a law degree.

Life

Education and family

Stanley Forman Reed was born in 1884 in the small town of Minerva, Kentucky, to a wealthy doctor . His father's religious views were Protestant , although he did not belong to any particular church. Stanley Forman Reed was the only child of his parents and received his education in private schools in Mason County . He then studied first at Kentucky Wesleyan College , a Methodist college in Winchester , where he received a BA degree in 1902 . Four years later he earned a second BA with a focus on economics and history at Yale College , where one of his teachers was the sociologist William Graham Sumner . In the following years he devoted himself from 1907 at the University of Virginia and from 1908 at Columbia University a law degree, which he finished without a degree. During a trip to France in 1909 he also studied civil and international law at the Sorbonne . He married a year earlier and had two sons.

After returning from France, he continued his legal training at a law firm in Kentucky. He was admitted as 1910 Lawyer and settled in Maysville , where he opened his own law firm. Two years later he was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives, where he served two two-year terms and, among other things, introduced bills on child labor and worker accident insurance. After the United States entered World War I in April 1917, he joined the US Army, where he held the rank of lieutenant . With the end of the war he resumed his legal practice in a law firm in Maysville, in which he later became a partner. He became known beyond Kentucky due to his successful work and represented a number of large companies such as the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in the following years . He and his family settled on a farm near Maysville, where he raised cattle in his spare time.

Government offices

In November 1929, Stanley Forman Reed, a member of the Democratic Party , was appointed senior lawyer on the Federal Farm Board by Republican President Herbert C. Hoover because of his national reputation in the field of agricultural cooperative law . It was a federal institution that had been created to deal with the consequences of the Great Depression in the field of agriculture. He served in this capacity until December 1932 and then worked in the same position for the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), an independent federal agency providing financial support to states and municipalities as well as banks , railroad companies and other companies during the Great Depression. In this role he was jointly responsible for the creation of the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC), a state-owned company that was supposed to stabilize the prices of agricultural goods through buying and selling activities and thus ensure the economic survival of agricultural companies. The CCC was formed on the advice of Reed in October 1933 by a presidential decree from Franklin D. Roosevelt and developed into the basis for all measures of the New Deal in the field of agriculture.

He also supported the views of Herman Oliphant , legal advisor to the United States Treasury Department , who, contrary to the position of Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau , held the RFC's requested gold purchase by the RFC to be legally permissible. This action took place in 1933 should repeal of after the initial gold standard of the gold price stabilized or increased. Roosevelt had enforced the abolition of the gold standard and measures to restrict private gold ownership in order to stop the previously legally guaranteed exchange of US dollars for gold and thus the increasing demand for the gold reserves of the United States. In March 1935, Reed assumed the office of United States Solicitor General . In this capacity, he represented the government before the Supreme Court in a number of constitutional proceedings involving various laws passed under the New Deal. After he was initially unsuccessful in some of these proceedings, he succeeded in 1937 to defend important government bills before the Supreme Court. The record of his work as Solicitor General is average to good. A number of the cases he successfully defended on behalf of Roosevelt's government resulted in judgments that continue to be considered fundamental decisions in the history of the Court.

Supreme Court Justice

After Judge George Sutherland, aged 78, withdrew from the Supreme Court in January 1938, President Roosevelt nominated Stanley Forman Reed as his successor on January 15, 1938. Ten days later he was unanimously confirmed by the Senate without any significant objections and took office on January 31, 1938; thus he was the second judge nominated by Roosevelt after Hugo Black . Robert H. Jackson followed him as Solicitor General . Reed, who wrote 339 opinions during his tenure on the Supreme Court, was generally considered to be moderate and in many cases cast the fifth vote, which is decisive for judgment. He wrote the majority opinion in 231 decisions, an affirmative comment in 29 cases and a deviating minor opinion in 88 cases. Early in his tenure, Reed often voted with the liberal-minded justices of the court, led by Harlan Fiske Stone . By the mid-1940s, however, the content of the court changed increasingly, so that it was more and more a member of the conservative wing.

After Stone's death in April 1946, Reed himself was interested in the position of presiding judge, but President Harry S. Truman appointed Fred M. Vinson instead . During the court's tenure under Vinson's leadership, Reed's views often echoed those of Vinson, who, like Reed, was from Kentucky. He also mostly voted together with the other judges nominated by Truman, so that in this phase he often represented the majority opinion. Following the appointment of Earl Warren to the presiding judge in 1953, Reed was from the mid-1950s increasingly dissenting from that differed from the court majority, as it was of the view the that jurisprudence of the Court away would be far from his own views. At the end of his tenure in 1957, he was considered the most conservative of the eight judges Roosevelt had nominated. This change in the perception of its work resulted in part from the shift in the Court's focus from commercial law issues during the New Deal era to civil rights issues and criminal procedural issues in the post-World War II period.

The decisions formulated by Stanley Forman Reed included United States v. Rock Royal Cooperative, Inc. (307 US 533, 1939), which made the Agricultural Marketing Agreement Act of 1937 constitutional. This New Deal law gave the Department of Agriculture the ability to set minimum prices for certain agricultural goods in foreign and inter-state trade. He also wrote the majority opinion in the Smith v. Allwright (321 US 649, 1944), which overturned a previous decision on the legality of refusing African-Americans to participate in political primaries , and in the decision of Morgan v. Virginia (328 US 373, 1946), which dismissed racial segregation laws in public transportation across state lines as unconstitutional. The lawsuit underlying this case was directed against a law of the state of Virginia and was brought before the court by the African-American civil rights activist Irene Morgan , who was represented by the later constitutional judge Thurgood Marshall .

Other cases in which Reed formulated the majority opinion were Pennekamp v. Florida (328 US 331, 1946), which concerned the freedom of expression guaranteed by the first amendment in a case in which a journalist had received a subpoena for disregard of the court after the publication of two critical articles about a court in Florida , and McCollum v. Board of Education (333 US 203, 1948) on the separation of religion and state in religious education in state schools. In the Adamson v. California (332 US 46, 1947) on the question of whether the provisions of the fifth constitutional amendment are part of the inalienable fundamental rights formulated in the Bill of Rights based on the principle of legal certainty formulated in the 14th constitutional amendment , he wrote the court position. The attitude of the court in this decision, taken by five votes to four judges, that the 14th Amendment does not protect the right under the fifth amendment to refuse to testify against oneself in dealing with national courts, was adopted in several decisions in the 1960s revised by the Court of Justice.

Stanley Forman Reed was also involved in the Brown v. Board of Education (347 US 483, 1954), which is considered one of the most important in the history of the Court and marked the end of legally sanctioned racial segregation in state schools in the United States. However, believing that segregation was not inherently discriminatory, he only endorsed the ruling after Presiding Judge Earl Warren convinced him that the unanimity of the Court on this case was in the absolute best interests of the country and the court be. According to observers and Warren, Reed's support was instrumental in the social acceptance of Brown v. Board of Education at. According to John Fassett, Reed, who destroyed all of his documents and notes relating to this decision, had previously drafted a dissenting opinion. His colleague Felix Frankfurter , with whom he was closely connected during the 18 years they worked together, considered Reed's decision to move to Brown v. Board of Education to vote with the majority of the courts as its most significant contribution to the development of the country. Reed himself also saw this judgment as the most important of his judicial career.

Withdrawal from judicial office and death

Stanley Forman Reed's work on the Supreme Court, according to his law clerk John Fassett and former presiding judge Warren E. Burger, was marked by a strong zeal for work and a devotion to the court as an institution. On the other hand, however, he found the writing of judgments tedious and was therefore less likely than his colleagues to be given the task of drafting the court opinion. In addition, he wrote only a few notable decisions and largely avoided public statements that went beyond his statements in the verdicts. In his statements, which were mostly briefly worded, he usually limited himself to the facts of the respective case and the relevant laws.

On February 25, 1957, Stanley Forman Reed, who, according to the memories of his law clerks John Sapienza and John Fassett, was always friendly and non-arguing in his demeanor and in dealing with his fellow judges and employees, withdrew from in good health at the age of 72 returned to his position at the Supreme Court. In the 19 years of his service, he had served with Charles Evans Hughes , Harlan Fiske Stone , Fred M. Vinson and Earl Warren under four different presiding judges and had worked with 18 fellow judges. His successor in office was Charles Evans Whittaker . In November of the same year Dwight D. Eisenhower nominated him for the chairmanship of the Commission on Civil Rights . Reed rejected the nomination in early December 1957, however, because he believed that his work in this commission could damage the respect for the independence of the federal judiciary.

In the following years he served as a judge in lower federal courts, including until 1966 in 87 cases of the Federal Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia and also until 1970 in 40 cases in the Court of Claims . Of the 17 decisions that he wrote at the Federal Court of Appeals, six reached the Supreme Court through the courts. Its judges overturned one of these decisions, while in the five other cases the petition for a review ( Petition for Writ of Certiorari ) was rejected. At the Court of Claims he gave an opinion in 30 judgments. Stanley Forman Reed became the first former Supreme Court judge to regularly exercise post-retirement opportunities in the lower courts.

After he and his wife lived in an apartment in the Mayflower Hotel in Washington during his time as a judge, they lived in a retirement home in Huntington on Long Island from 1976 , where he died in 1980. At 95, he reached the highest age of any previous Supreme Court judge. In addition, he was the last judge in the history of the court without a law degree. He was buried in Maysville. His estate is held at the University of Kentucky .

Reception and aftermath

Legal philosophical and political views

With regard to his legal philosophy , Stanley Forman Reed, together with his colleague Felix Frankfurter, was a proponent of judicial restraint (judicial moderation), a position between the literal interpretation of the constitution by the representatives of strict constructionism (strict interpretation of the law) and that of judicial activism (judicial activism) designated contemporary interpretation of the Constitution as a "living document" (living document) . This attitude resulted from his experience as Solicitor General defending the laws of the Roosevelt government before the Court. Like the other Roosevelt nominees, he believed that the Court should be cautious about the legislature and the executive .

In the socio-economic field, Reed usually took progressive views such as supporting regulatory government action in the economy and strengthening civil rights and the role of trade unions . On some issues such as freedom of expression , national security and certain social issues such as the rights of defendants , however, he sometimes took conservative positions. However, he was regarded as an energetic opponent of censorship and supported in most of the judgments on the first amendment to the constitution an expansion of the resulting rights.

Within the Democratic Party, he positioned himself as a supporter of Woodrow Wilson's progressivism and of Roosevelt's social and economic reforms of the New Deal. In contrast, George Sutherland, his predecessor on the Supreme Court, was one of the four horsemen- termed block of four conservative judges who consistently opposed the New Deal legislation. Reed, on the other hand, saw the control of the economy through an appropriate economic policy as well as the improvement of American society as fundamental tasks of the government. He saw few restrictions on the powers of Congress or the President, particularly in the area of national security.

Awards and recognition

Stanley Forman Reed received honorary doctorates from Yale University (1938), the University of Kentucky (1940), Columbia University (1940), Kentucky Wesleyan College (1941) and the University of Louisville (1947). The University of Virginia presented him with the Outstanding Alumnus Award in 1961 . At the courthouse of the Mason County (Mason County Courthouse) in Maysville, a plaque commemorates his work as solicitor general and as a Supreme Court Justice. In addition, a street in Maysville where his office was located is named after him.

Under the title "New Deal Justice: The Life of Stanley Reed of Kentucky" appeared in 1994 a monographic biography with a length of around 770 pages on the life and work of Reed. In a survey entitled "Rating Supreme Court Justices," which the law professors Albert Blaustein from Rutgers University and Roy M. Mersky of the University of Texas at 65 university teachers for legal or political science and history conducted in 1970, was Stanley Forman Reed's work was rated in the third highest of five possible categories and therefore rated as “average”.

literature

- John D. Fassett: New Deal Justice: The Life of Stanley Reed of Kentucky. Vantage Press, New York 1994, ISBN 0-53-310707-5

- Daniel L. Breen: Stanley Forman Reed. In: Melvin I. Urofsky: The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. Garland Publishers, New York 1994, ISBN 0-81-531176-1 , pp. 367-372

- Reed, Stanley Forman. In: James Stuart Olson : Historical Dictionary of the Great Depression, 1929-1940. Greenwood Press, Westport 2001, ISBN 0-31-330618-4 , pp. 231/232

- Stanley Forman Reed. In: Michael E. Parrish: The Hughes Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara 2002, ISBN 1-57-607197-9 , pp. 116-118

- Stanley Forman Reed. In: Peter G. Renstrom: The Stone Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara 2001, ISBN 1-57-607153-7 , pp. 52-56

- Stanley Forman Reed. In: Michal R. Belknap: The Vinson Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara 2004, ISBN 1-57-607201-0 , pp. 48-51

- Stanley Forman Reed. In: Melvin I. Urofsky: The Warren Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara 2001, ISBN 1-57-607160-X , pp. 38-40

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Stanley Forman Reed. In: John E. Kleber: The Kentucky Encyclopedia. University Press of Kentucky, Lexington 1992, ISBN 0-81-311772-0 , p. 760

- ↑ a b c d University of Kentucky Libraries: Stanley F. Reed Collection, 1926–1977 - Biography ( Memento of the original from April 20, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (accessed on June 13, 2010)

- ^ Stanley Forman Reed (1938-1957). In: Congressional Quarterly's Guide to the US Supreme Court. Congressional Quarterly, Inc., Washington 1979, ISBN 0-87-187184-X , p. 850

- ↑ a b c d See Peter G. Renstrom, Santa Barbara 2001, p. 52

- ↑ a b c d e See Michal R. Belknap, Santa Barbara 2004, p. 48

- ^ Federal Judicial Center - Biographical Directory of Federal Judges: Reed, Stanley Forman, (accessed June 6, 2010)

- ↑ a b c George Goodman Jr .: Ex-Justice Stanley Reed, 95, Dead; On Supreme Court From '38 to '57. In: The New York Times . 4th edition, 1980, p. A23

- ↑ a b See James Stuart Olson, Westport 2001, p. 231

- ^ Arthur M. Schlesinger: The Age of Roosevelt 1933-1945. Second volume: The Coming of the New Deal. Houghton Mifflin, Boston 2003, ISBN 0-61-834086-6 , p. 239

- ↑ a b c See James Stuart Olson, Westport 2001, p. 232

- ↑ a b See Michal R. Belknap, Santa Barbara 2004, p. 50

- ↑ a b c d e f See Melvin I. Urofsky, New York 1994, p. 367

- ^ Marian Cecilia McKenna: Franklin Roosevelt and the Great Constitutional War: The Court-packing Crisis of 1937. Fordham Univ. Press, New York 2002, ISBN 0-82-322154-7 , p. 20

- ^ Warren E. Burger : Stanley Reed. In: The Supreme Court Historical Society 1981 Yearbook. The Supreme Court Historical Society, Washington DC 1981, pp. 5–7 (especially p. 5)

- ↑ a b c See Michael E. Parrish, Santa Barbara 2002, p. 116

- ↑ a b See Peter G. Renstrom, Santa Barbara 2001, p. 53

- ^ John D. Fassett: The Buddha and the Bumblebee: The Saga of Stanley Reed and Felix Frankfurter. In: Journal of Supreme Court History. 28 (2) / 2003. Supreme Court Historical Society, pp. 165–196, ISSN 1059-4329 (specifically pp. 182/183)

- ^ John D. Fassett: The Buddha and the Bumblebee: The Saga of Stanley Reed and Felix Frankfurter. In: Journal of Supreme Court History. 28 (2) / 2003. Supreme Court Historical Society, pp. 165–196, ISSN 1059-4329 (specifically p. 187)

- ^ A b c d e Wayne K. Hobson: John D. Fassett. New Deal Justice: The Life of Stanley Reed of Kentucky. New York: Vantage. 1994. Book review in: American Historical Review. 101 (1) / 1996. University of Chicago Press, ISSN 0002-8762 , pp. 253/254

- ↑ United States v. Rock Royal Cooperative, Inc. (307 US 533, 1939) (accessed September 26, 2010)

- ^ Smith v. Allwright. (321 US 649, 1944) (accessed September 26, 2010)

- ↑ Morgan v. Virginia. (328 US 373, 1946) (accessed September 26, 2010)

- ↑ Pennekamp v. Florida. (328 US 331, 1946) (accessed September 26, 2010)

- ↑ McCollum v. Board of Education. (333 US 203, 1948) (accessed September 26, 2010)

- ↑ Adamson v. California. (332 US 46, 1947) (accessed September 26, 2010)

- ↑ Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. (347 US 483, 1954) (accessed September 26, 2010)

- ↑ a b c See Michal R. Belknap, Santa Barbara 2004, p. 51

- ^ John D. Fassett: The Buddha and the Bumblebee: The Saga of Stanley Reed and Felix Frankfurter. In: Journal of Supreme Court History. 28 (2) / 2003. Supreme Court Historical Society, pp. 165-196, ISSN 1059-4329

- ^ A b Warren E. Burger : Stanley Reed. In: The Supreme Court Historical Society 1981 Yearbook. The Supreme Court Historical Society, Washington DC 1981, pp. 5-7 (especially p. 6)

- ^ John D. Fassett: The Buddha and the Bumblebee: The Saga of Stanley Reed and Felix Frankfurter. In: Journal of Supreme Court History. 28 (2) / 2003. Supreme Court Historical Society, pp. 165–196, ISSN 1059-4329 (specifically p. 165)

- ↑ a b See Melvin I. Urofsky, Santa Barbara 2001, p. 40

- ^ John D. Fassett: The Buddha and the Bumblebee: The Saga of Stanley Reed and Felix Frankfurter. In: Journal of Supreme Court History. 28 (2) / 2003. Supreme Court Historical Society, pp. 165–196, ISSN 1059-4329 (specifically p. 166)

- ^ A b Minor Myers III: The Judicial Service of Retired United States Supreme Court Justices. In: Journal of Supreme Court History. 32 (1 )/2007. Supreme Court Historical Society, pp. 46–61, ISSN 1059-4329 (specifically pp. 49–51)

- ↑ a b See Peter G. Renstrom, Santa Barbara 2001, pp. 53/54

- ↑ See Melvin I. Urofsky, New York 1994, p. 371

- ↑ See Peter G. Renstrom, Santa Barbara 2001, p. 54

- ↑ a b University of Kentucky Libraries: Stanley F. Reed Collection, 1926–1977 - Memorabilia Series ( Memento of the original from April 20, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (accessed on June 6, 2010)

- ^ Warren E. Burger : Stanley Reed. In: The Supreme Court Historical Society 1981 Yearbook. The Supreme Court Historical Society, Washington DC 1981, pp. 5-7 (especially p. 7)

- ↑ Rating Supreme Court Justices. In: Henry Julian Abraham: Justices, Presidents and Senators: A History of the US Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Bush II. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham 2007, ISBN 0-74-255895-9 , pp. 373-376

Web links

- The Oyez Project - Stanley Reed (English)

- United States Department of Justice - Office of the Solicitor General: Stanley Reed (English)

- University of Kentucky Libraries: Stanley F. Reed Collection, 1926–1977 (English)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Reed, Stanley Forman |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American lawyer, United States Supreme Court Justice |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 31, 1884 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Minerva , Kentucky |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 2, 1980 |

| Place of death | Huntington , New York |