Gold price

| gold | |

|---|---|

| Country: | global |

| Subdivision: | 1 troy ounce = 31.1034768 grams |

| ISO 4217 code : | XAU |

| Abbreviation: | no |

|

Exchange rate : (03 August 2020) |

1 XAU = 1,958.55 USD |

The gold price is the market price for the precious metal gold . It arises on commodity exchanges through the global interplay of supply and demand and is mainly quoted in US dollars . The most important gold prices in Europe are in Zurich, Paris and London.

Important influencing factors are the dollar exchange rate, interest rates and the oil price as well as the prices of other precious metals (e.g. silver , platinum and palladium ) and metals (e.g. copper and rare earths ). Emotions also play a role on the commodity exchanges, e.g. B. Fears of inflation , political events, speculation and long-term expectations.

history

Antiquity

First gold coins under King Croesus

Around 560 BC In BC, the Lydian king Croesus had gold coins , uniform in size and value, stamped for the first time , which, in addition to a propaganda function, also represented a - limited - quality standard for the precious metal . These early gold and silver coins in Asia Minor , in which the original bar shape was still recognizable, were the first Kurant coins .

Gold and other metals fulfilled the classic monetary functions (medium of exchange, means of payment, value meter and store of value / store of value) as early as the beginning of the 3rd century BC. In the ancient Orient and Egypt . However, the palace economy in connection with the oikos economy as well as the subsistence production connected with it was a hindrance to the development of a money economy , since goods that were not self-produced were mostly procured by way of exchange or service obligation. Coin money therefore only caught on later and initially only in a few branches of the economy.

Gold standard in the Roman Empire

Around 225 BC The first gold coins were struck in the Roman Empire . The Romans took over the coinage from the Greeks. Under Julius Caesar more and more gold coins were minted , including the aureus .

As the empire expanded, ever larger amounts of silver flowed into Rome. A large part of the state expenditure was financed by the minting of silver coins, which in the following centuries initially led to currency devaluation and in the 3rd century AD to the complete collapse of the Roman silver currency . The Roman citizens, too, increasingly no longer had confidence in ever new forms of coins, which tended to have an ever decreasing silver content, so that older coins in particular were hoarded or melted down. Since money lost much of its importance, the wages of the Roman soldiers, for example, had to be paid directly in grain.

In response, Emperor Constantine the Great replaced the silver currency with a stable gold currency around AD 310 . The so-called solidus served as a means of payment . The value of the gold coin was 1/72 of the Roman pound (usually 4.55 grams), which was sometimes expressed by the number LXXII on the coin. So 72 solidi made one pound and 7200 solidi one Roman hundredweight ( centenarium ).

middle Ages

Gold coins as key currencies

After the end of late antiquity around 600, the solidus remained the most important currency in Eastern Europe. It was the key currency in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East until the beginning of the 12th century . The reasons for this are the high gold content and the resulting stability of the gold currency. With the decline of Byzantium, its currency also deteriorated.

The gold circulation within the framework of state institutions per se decreased in the early Middle Ages . On the other hand, money increasingly developed into a medium of exchange that served trade and market activities. The original gold standard lost its importance as a means of payment and was only hoarded as a kind of store of value. Most empires switched to silver because gold was rarer and more expensive than silver. Silver only showed the pure arithmetic relation to gold.

With the crusades and the increasingly pronounced long-distance trade, the gold standard was reintroduced. The florin and gold guilder from Florence , the ducat ( zecchine ) from Venice and the Genovino from Genoa spread throughout Europe and became international reserve currencies of the Middle Ages.

These currencies originated from trade with North Africa ( Maghreb ). There the merchants could buy cheap African gold with European silver. In order to sell the gold acquired in the silver trade or the even more lucrative salt trade at a profit, gold coins were the appropriate medium. Gold coins were a commodity in Europe because their price compared to silver coins was initially not fixed, but rather dependent on the value ratio of the two precious metals. Gold had a considerably better price in Europe than silver (1:10 to 1:12 in Europe, 1: 6 to 1: 8 in the Maghreb). In this way good profits were made and at the same time a stable value means of payment came onto the market.

Permanent deflation in the late Middle Ages

A general decline in mining began in the 14th and 15th centuries. Production fell; the mining technical development stagnated. The long-lasting depression in the economies of Europe in the late Middle Ages can be explained by permanent deflation , caused by a lack of precious metals as a result of the decline in gold and silver production and a decline in population .

The causes of the crisis in the mining industry were inadequate mining technology and problems with work and company organization. There was also a shortage of workers who had died from the plague epidemics . Since the total number of mines was small, the amount of gold grew only marginally. As a result, gold increased in value.

The extent to which the scarcity of the money supply led to a lack of means of payment also depended on the population development . Plague, wars and famines decimated the population of the countries of Europe by a third from 1340 to 1450. Coin production fell by around 80 percent in the same period. Thus the demand for means of payment exceeded the supply. Since gold coins were scarce and valuable, they were increasingly being hoarded. This withdrew the precious metal from the circulation of money, thereby reducing its velocity and exacerbating deflation. It is assumed that the gold value only fell again with the discovery of America in 1492 and the gold flowing from there to Europe and thus the permanent deflation ended.

Early modern age

Inflation from the discovery of America

As a result of the subjugation and plundering of Central American cultures in the 16th century, many shipments of gold and silver came to Europe. From 1494 to 1850 an estimated 4700 tons of gold are said to have come from South America , not counting the silver that became means of payment in the form of gold coins ( coin shelf ) or entered the state treasury.

The increase in gold had an impact on the world's economies. Prices began to rise worldwide. In Spain, inflation was 400 percent throughout the 16th century. That is 1.6 percent per year. The price revolution spread from there across Europe and as far as Asia. The phenomenon of steady inflation, which is considered normal today, did not exist in Europe before the 16th century. In Germany, the price of rye was 9 grams of gold in 1461/70 and 35 grams of gold in 1611/20. That corresponded to a nearly four-fold increase within 150 years. The so-called price revolution showed people how purchasing power depends not only on goods but also on money on supply and demand.

According to the cost of production theory of money (or according to the labor theory of value ), the large gold and silver imports from South America after the discovery of America did not lead to inflation in Europe because the large amount of gold was compared to a comparatively small amount of commodities - that is what the quantity theory of money says - but because suddenly less labor was required to extract a certain amount of gold or silver. The expansion of the money supply (the amount of gold and silver in circulation) was only a symptom of the suddenly lower labor value of the precious metals.

Coin deterioration

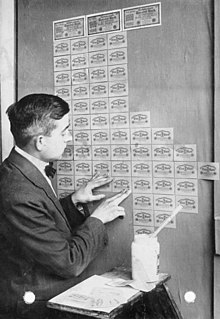

During the tipper and wipper era , the fraudulent coin valuation led to rising gold and silver prices . Whole-valued coins were sorted out using a high-speed scale in order to either melt them down or cut the edges and use the metal obtained in this way to produce new coins with the addition of copper . The currency depreciation can be recognized by the ratio of gold gulden to kreuzers (Kurant coin): If the value of a gold gulden was 60 kreuzers in 1559, it rose to 180 kreuzers by 1620 and exceeded the limit of 1000 kreuzers in 1622.

The Seven Years' War brought with it a massive deterioration in coins (inflation). The coins of this time mirrored to the citizen in the precious metal content full (pre-war) Kurant coins by their minting, but were in reality inferior in their fineness . Frederick the Great used it to finance the war that began in 1756. The royal mint made a significant profit by making and issuing such coins . The banker and coin leaseholder Veitel Heine Ephraim (1703–1775) from Berlin was primarily responsible for this, and he produced these coins, which are called Ephraimites after him .

Example for the value of two golden 5 thaler coins (August d'or) from 1758 according to a Prussian valuation table from 1820: "Two" Middle August d'Or "(nominally 10 thaler) = 6 thaler, 21 groschen, 6 Pfennige (Prussian. Courant) ”, that is, at least one and a half thalers of gold were missing from the face value of each 5 thaler coin.

Determination of gold and silver exchange in Great Britain

In Great Britain, coinage was essentially based on silver until the beginning of the 18th century, and gold coins were subject to great fluctuations. On September 21, 1717, Isaac Newton , head of the royal mint, set the price for a guinea in silver, fixing a ratio of 21 shillings to one guinea. The rate for exchanging pounds sterling for gold was £ 3.89 an ounce . Newton set the gold price for silver too low. Silver was now relatively more expensive than gold and was therefore pushed out of circulation over time.

Since December 22, 1717, the British currency was de facto exchangeable for gold at fixed gold parity through a royal proclamation . On May 10, 1774, the British Parliament made the transition to the later legal gold standard . The silver coin was eliminated as a means of payment for amounts over 25 pounds and decreed that it should only be accepted by weight.

From 1797 to 1821, the convertibility of the British currency was suspended due to the Napoleonic Wars . During this time, a great deal of gold flowed abroad from Great Britain or was hoarded. Ultimately, the British government lifted the obligation to redeem gold for paper banknotes. After a while there were two prizes. The stable prices of goods are expressed in gold and the rising prices of goods are expressed in paper money. A devaluation of the banknotes against gold did not occur until September 1799; but then it developed rapidly and became apparent both in the unfavorable exchange rates and in the high price of gold bullion. While in 1797 the troy ounce of standard gold cost 77.06 schillings, its price rose to 84 schillings in 1801, to 90 schillings in 1809 and to 108 schillings in 1814. The gold price rose 40.3 percent over the entire period.

The directors of the Bank of England denied that the notes were devalued; they maintained that the notes could not go down in value at all as long as they were issued against undoubtedly solid, business-based bills of exchange with a short expiry date. A parliamentary investigation into the causes of the high gold price and the fall in exchange rates gave rise to the Bullion Report in 1810. The commission appointed showed in the report that it was not the gold that had risen, but that the notes had actually fallen, that there were too many notes in circulation and that the issue of the same had lost its natural control due to the suspension of redemption; the cash payment should therefore be resumed as soon as possible. In 1821 the gold price stood at the now legal nominal value of 77.11 schillings.

Bimetalism

For Prussia of the 18th and early 19th centuries, one can speak of an early form of bimetallism , since for the more valuable payments, mostly payments to foreign countries for high-quality goods such as luxury items, often with golden Friedrich d'or and for the usual payments in Inland the silver thalers were used. At that time there was no legally set fixed rate between gold and silver, but there was a certain legally tolerated fluctuation range. In Germany there was a “legally prescribed bimetallism” until 1907, when the simple silver Zollvereinstaler ran around as a Kurant coin next to the gold coins, which is often referred to in the literature as the “ limping gold currency ”.

The basis of the actual bimetalism was the contractual or legal stipulation of a fixed value relationship between the coin metals used within a country or the financially strongest countries in a currency union . In France (from 1795) and later in the Latin Monetary Union (from 1865) this ratio was fixed at 1: 15.5. In the Latin Monetary Union, bimetallism expressed itself in the fact that the fine weight and the value ratio around 1870 of 2 silver 5-franc pieces to a golden 10-franc piece ( gold francs ) were 15.5 to 1.

In the United States Constitution , bimetalism was established as the currency standard in 1789. The currency laws allowed the simultaneous minting and circulation of gold and silver coins. The legal exchange ratio of silver to gold was 15: 1 (that is, one gram of gold had the same value as 15 grams of silver). In 1792, Alexander Hamilton became the first US Treasury Secretary to propose the creation of a gold and silver monetary system. With the Coinage Act of February 12, 1873, the USA gave up bimetallism.

Classic gold standard 1816 to 1914

With the introduction of the gold standard , the so-called obligation of convertibility arose, that is, it was theoretically possible for every citizen at any time to exchange their cash for the corresponding amount of gold at the central bank . The gold parity denotes the exchange ratio. In practice, depositing the currency with gold acted as a hedge against excessive cash inflation .

Pound sterling becomes the reserve currency

On June 22, 1816, Great Britain declared the gold standard to be the national currency with the Coin Act ("Lord Liverpool's Act"). The basis was the sovereign with a face value of one pound sterling at 20 shillings . The law defined that from 12 troy ounces of 22-carat gold ( "Crown Gold", 916 2 / 3 /1000 fineness) £ 46 14s 6d, so be emboss 46.725 pounds sterling. This resulted in a fixed parity of 7.322381 g fine gold per pound sterling and a gold price of £ 4 4s 11 5 ⁄ 11 d (= £ 4.247727) per troy ounce of pure gold. On May 1, 1821, full convertibility of the pound sterling into gold was guaranteed by law.

When other countries pegged their exchange rates to the British currency, the pound became the key currency. The adjustment was made in particular due to the increasing British dominance in international financial, economic and trade relations. Two thirds of world trade in the 19th century was in British currency and most of the currency reserves were held in sterling.

The gold standard was an exception in the world economy in the early 19th century. Most nations only started to introduce gold currencies later (Canada 1854, Germany 1871, France and Switzerland 1878, USA 1879, Italy 1884, Austria-Hungary 1892, Russia and Japan 1897).

Civil War and Gold Speculation in the USA

Between 1810 and 1833 the silver standard was de facto in the USA . The price of gold was $ 19.39 per troy ounce . With the Coinage Act of June 27, 1834 and minor changes in 1837, the legal exchange ratio of gold to silver was set at a ratio of 1:16 and thus de facto the gold standard was introduced. The gold dollar was now defined at 23.22 grains of fine gold, whereby the gold price was fixed at 20.671835 US dollars per troy ounce. The slight overvaluation of gold led to silver being pushed out of circulation. The California gold rush (1848–1854) reinforced this trend.

During the Civil War (1861-1865), the military conflict between the southern states that left the USA - the Confederation - and the northern states that remained in the Union , the gold price rose on July 1, 1864 to a high of 59.12 US dollars. Adjusted for inflation , US $ 990.66 had to be paid at that time.

On September 24, 1869, gold speculation on the New York Stock Exchange resulted in the first " Black Friday ". Attempts by speculators James Fisk and Jay Gould to get the gold market under their control failed and led to the market collapse. The gold price rose in the course of trading to $ 33.49 (adjusted for inflation, $ 646.99). By September 20, 1869, Fisk and Gould had brought New York City's gold reserves under their control to such an extent that they could soar the price. Gold demand was halted on September 24th when the government released gold reserves for free trade. A short-term financial crisis in the USA was the result.

In 1879 the US de facto returned to the gold standard. The fixed price was back at $ 20.67. With the “Gold Standard Act” of March 14, 1900, the gold standard became official currency.

Gold standard in Germany

In the German Reich , the introduction of the gold standard was prepared by several laws and ordinances. The “Law on the Minting of Gold Coins” of December 4, 1871 introduced gold coins into the German monetary system in addition to talers and guilders . The Coin Act of July 9, 1873 made the gold mark the only Reich currency by January 1, 1876 at the latest. It was stipulated that a metric (inch) pound of fine gold should be used to mint 1,395 marks in coins of 5, 10 and 20 marks. (The coins also contain some copper; their fineness is 900/1000.) With this, the mark was defined as 0.358423 g fine gold and the gold price set at 2790 marks per kilogram or 86.7787 marks per troy ounce. With the “Ordinance concerning the introduction of the Reich currency” of September 22, 1875, the gold currency finally came into force on January 1, 1876.

| currency | Troy ounce | kilogram |

|---|---|---|

| Pound Sterling | 4,247727 | 136.5676 |

| U.S. dollar | 20.671835 | 664.6149 |

| mark | 86.778700 | 2790.0000 |

|

LMU (Franc, Lira, etc.) |

107.134198 | 3444.4444 |

Gold prices below the gold standard

The table on the right shows the gold price in various currencies under the gold standard, as it resulted automatically from the defined gold parities . In fact, the prices were slightly different, as the costs of transporting and processing gold are not included. For example, the Banking Act of March 14, 1875 obliged the German Reichsbank to buy gold bullion at a small discount (1,392 instead of 1,395 marks per 500 g pound) against banknotes.

Between the wars 1918 to 1939

Gold currency standard

With the beginning of the First World War , the obligation to redeem gold in most countries ended in 1914 (on August 4, 1914 in the German Reich). Instead of the gold standard, in accordance with the recommendations of the Genoa Conference, foreign exchange was usually managed. Between 1922 and 1936 there were gold core or gold foreign currency currencies without any obligation to redeem private individuals. The central banks intervened in the foreign exchange market to defend the so-called gold points. Only the transaction costs allowed a small range of fluctuation within the gold points, which marked the limit of this possible price range.

The uncoordinated return to gold parities with the result of over- and undervaluation of important currencies led to the collapse of the restored gold standard as an international monetary system. The trigger was the suspension of the Bank of England's obligation to redeem gold for the British pound on September 21, 1931. In the following period, there were devaluations of other currencies and monetary policy disintegration prevailed.

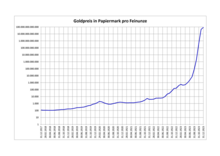

Hyperinflation in Germany

In Germany, the lost First World War and the associated reparations , which used up the state's gold reserves , led to the forced conversion to non-gold-backed money (trust currency or fiat money ). This was only made possible by the hyperinflation of 1923 and led to strong gold demand.

With the conversion of the war economy to peace production, numerous demobilized soldiers were integrated into the economy. The integration took place through the reduction of working hours and the taking on of further national debts . The government-sponsored demand should accelerate the growth of the economy. As wages and manufacturing costs were low , the goods produced could be exported abroad at low cost . In 1921 and 1922 there was almost full employment in the German Reich . The weak German currency temporarily encouraged export-oriented German industry to re - enter world trade. In the long term, the effects on the economy were serious.

The economist Ludwig von Mises wrote in 1912 in “Theory of money and the means of circulation” about the price of wealth created by credit: “The recurring occurrence of boom periods followed by periods of depression is the inevitable result of repeated attempts to attribute the market interest rate through credit expansion reduce. There is no way to prevent the final collapse of a boom created by credit expansion. The only alternative is: Either the crisis arises earlier through the voluntary termination of a credit expansion - or it arises later as a final and total catastrophe for the monetary system in question. "

Hyperinflation developed under the burden of reparations payments, the occupation of the Ruhr and the attempt to provide financial support to the occupied territories . In November 1923 the Reichsbank issued a bill for one trillion marks, a total of 10 billion bills were printed during this time. Since the funds were insufficient to stop the fall in prices, additional emergency notes from cities, municipalities and companies were issued - a total of more than 700 trillion marks in emergency money and around 524 trillion marks from the Reichsbank. Due to inflation, real wages fell to 40 percent of the pre-war level, which led to the impoverishment of large sections of the population.

| year | Of living cost index in gold |

Wages in gold for ... | Unemployment rate in % |

Stock index of stat. Reich Office in gold |

Gold value of ... | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| skilled workers | unskilled workers | 100 paper marks | Troy ounces of gold | ||||

| 1913 | 100 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 2.9 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100 |

| 1920 | 77 | 50.4 | 67.2 | 3.8 | 14.43 | 7.33 | 100 |

| 1921 | 63 | 46.8 | 62.9 | 2.8 | 17.92 | 5.21 | 100 |

| 1922 | 42 | 29.2 | 39.7 | 1.5 | 9.35 | 0.98 | 100 |

| 1923 | 59 | 36.5 | 48.8 | 9.6 | 16.15 | 0.0083 | 100 |

| 1924 | 114 | 89.6 | 101.7 | 13.5 | 6.39 | 98.80 | 100 |

Loss of value of the German currency

| date | 1 USD | 1 troy ounce gold exchange Cologne |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Berlin Stock Exchange |

Cologne Stock Exchange |

||

| Nov 13 | 1.26 | 3.90 | 80.61 |

| Nov 14 | 1.26 | 6.85 | 141.59 |

| Nov 15 | 2.52 | 5.80 | 119.89 |

| Nov 16 | 2.52 | 6.50 | 134.36 |

| Nov 17 | 2.52 | 6.70 | 138.49 |

| 19 Nov | 2.52 | 9.85 | 203.60 |

| Nov 20 | 4.20 | 11.70 | 241.84 |

| Nov 22 | 4.20 | 10.20 | 210.83 |

| 23 Nov | 4.20 | 10.50 | 217.04 |

| Nov. 24 | 4.20 | 10.25 | 211.87 |

| Nov 26 | 4.20 | 11.00 | 227.37 |

| Nov 27 | 4.20 | 10.20 | 210.83 |

| Nov 28 | 4.20 | 9.40 | 194.30 |

| Nov 29 | 4.20 | 8.50 | 175.70 |

| Nov 30 | 4.20 | 7.80 | 161.23 |

| 6 Dec | 4.20 | 4.90 | 101.28 |

| Dec 10 | 4.20 | 4.20 | 86.81 |

The ratio of gold to paper marks shows the decline in value of the German currency: at the end of December 1918, two paper marks had to be paid for one gold mark at the official rate, at the end of December 1922 it was already more than 1,550 paper marks and at the end of September 1923 around 56 million paper marks and at the height of the Inflation at the end of November 1923 one trillion paper marks. US $ 20.67 - the price for 1 troy ounce of gold - officially corresponded to 86.81 trillion marks. With the issue of the Rentenmark as a new means of payment by the Deutsche Rentenbank , the currency reform began on November 15, 1923 . On November 20, 1923, the exchange rate of one Rentenmark was fixed with one trillion paper marks, one US dollar was equivalent to 4.20 Rentenmarks on the Berlin Stock Exchange .

The Rentenmark was only created for internal German payments, while the old Mark continued to be traded on the foreign exchange markets . The Rentenmark remained a purely domestic currency - according to the Foreign Exchange Ordinance of November 16, 1923, it was not allowed to be used for payments to foreigners or by residents abroad. The foreign currency was still the old paper mark, the official rate of which was lowered twice below the free exchange rate: on November 15 from 1.26 trillion marks to 2.52 trillion marks and on November 20, 1923 to 4.2 trillion marks for 1 U.S. dollar.

Even after that, the dollar achieved considerably higher prices on the New York Stock Exchange . It stood there on November 19 at 5.0 trillion, on November 26 at 8.3 and on November 27 at 7.1 trillion paper marks. The exchange rates in the British zone of occupation around Cologne , which were not subject to the foreign exchange laws of the German government, were even less favorable . On the Cologne stock exchange the free dollar rate rose on November 19 to up to 9.85 trillion and on November 20 to up to 11.7 trillion marks. One troy ounce of gold thus cost the equivalent of 241.84 trillion paper marks. The gold value of one troy ounce of gold, however, remained unchanged. A rising gold price only expresses how many units paper money loses in value compared to a fixed, unchanged reference value.

However, this speculation soon broke at the barriers that were set up by the measures taken for monetary contraction (restriction of the banknote circulation). As quickly as it had risen, the rate of the US dollar on the Cologne stock exchange also fell again. On November 27th it stood at 10.2 trillion, on November 28 at 9.4, on November 29 at 8.5, on November 30 at 7.8 and on December 6 at 4.9 trillion paper marks . On December 10, 1923, the free US dollar exchange rate fell back to the official Berlin market price of 4.2 trillion marks for 1 US dollar.

The goal was thus achieved. In the period that followed, as a result of the collapse of speculation and the increasingly noticeable shortage of money, foreign currency flowed into the Reichsbank, because only with it larger amounts of dollars could be sold against amounts in marks. This circumstance made it easier for the Reichsbank to maintain the fixed US dollar exchange rate. However, this did not solve the problems in the supply of foreign currency; the allocations still had to be limited to fractions of the amounts required. But the risk that the speculation and the associated devaluation of the paper mark on the foreign stock exchanges and in Cologne, confidence in the currency reform would wane, was averted.

The Reichsmark (RM) was introduced as a replacement for the completely devalued paper mark through the Coin Act of August 30, 1924 , after the currency had previously been stabilized by the introduction of the Rentenmark. The exchange rate from paper mark to Reichsmark was a trillion to one. A fictitious gold cover of 1/2790 kilograms of fine gold was legally assigned to one Reichsmark. This corresponded to the formal pre-war gold cover. In contrast to the gold mark, however, the Reichsmark was not a pure gold standard currency and therefore not redeemable at least partially in currency gold coins at the Reichsbank by the citizens. In terms of currency, inflation ended with the introduction of the Rentenmark and the Reichsmark.

Investments versus inflation

A comparison of gold and other investments shows their different development between 1913 and 1923. Very few investors were able to save or increase their wealth over the entire period, but some benefited from inflation. This also included the owners of German stocks, but only during the relatively short period of the actual hyperinflation from 1920 to 1923.

For private investors, trading in stocks remained difficult and of little market transparency throughout the war . To prevent panic selling, the stock exchanges had to close on July 30, 1914. With the ordinance on foreign securities of March 22, 1917, the Deutsche Reichsbank was given the legal possibility to forcibly confiscate foreign securities and to compensate the owners in paper marks. On January 2, 1918, official share trading was resumed on the stock exchanges. From 1920, the upward movement in share prices turned into the so-called catastrophe boom (English crack-up boom ). The stock index of the Reich Statistical Office rose from 274 points at the end of 1920 to 26.89 trillion points at the end of 1923 (base value 1913 = 100 points). During the same period, the cost of living index of the Reich Statistical Office increased from 1158 points to 124.7 trillion points (base value 1913 = 100 points). The real losses of German stocks between 1913 and 1923, i.e. adjusted for inflation, were around 80 percent.

Holders of interest-bearing securities suffered higher losses than stockholders . The bills of exchange for the war bonds to the state became worthless in 1923. The currency reform in Germany meant almost a total loss for the remaining interest-bearing securities. Credit lost value due to hyperinflation and was wiped out in 1923. 100 Mark savings deposits invested in 1914 only had the purchasing power of pennies. The life insurance were little supported by the state and therefore suffered heavy losses. The collapse in bond prices and hyperinflation wiped out the insured's accumulated assets.

Homeowners initially benefited from hyperinflation. The real value of their real estate loans fell accordingly, but the houses retained their value. In 1924, the German federal states levied house interest tax on residential property built before July 1, 1918 in order to skim off property assets that had been relieved by inflation. Homeowners should share in the cost of publicly subsidized housing. The federal states were able to decide independently on the structure of the tax, which led to large regional differences. In 1927/28 Saxony was at the top with a maximum tax rate of 51 percent of rental income , in Prussia it was 48 percent, in Bremen 20 percent. The tax had a devastating impact on the housing market. Numerous owners could not bear the burden and had to sell their properties, which caused property prices to collapse by up to 50 percent. On January 1, 1943, the tax was canceled, with the homeowners affected having to pay ten times the annual tax burden as a transfer fee.

Due to trade restrictions and the prohibition of private ownership from 1923 to 1931, precious metals temporarily became the asset class with the lowest fungibility (see gold ban ). At the height of inflation, only stocks could make real profits in paper marks; their possession was not a criminal offense. However, they were only suitable for short and medium-term storage of value. With bonds and savings deposits, there is a risk of default and creditworthiness, which arises from the fact that the debtor can default on payment or even become insolvent. The worse the credit rating , the higher the risk of default. Debtors with poor credit ratings must therefore offer a higher coupon or higher interest rate in order to remain attractive despite the risk of default. In contrast, gold does not accrue interest because there is no risk of default. It has the highest credit rating.

Gold did not generate any real profit during hyperinflation, but over the long term the precious metal retained its value like no other asset class. Anyone who owned gold bars, gold coins or the gold-backed US dollar could secure their assets and maintain their purchasing power. Compared to all asset classes, gold offered the best protection against loss of purchasing power.

The table compares the development of the cost of living of gold, gold marks, US dollars and stocks (including dividends and subscription rights ) from 1913 to 1923 (December each year). The stock markets were closed during the First World War. There are therefore no official price data and a stock index calculated by the Reich Statistical Office for this period. All data refer to the official prices on the Berlin stock exchange. The free exchange rate of the US dollar in paper marks was at times almost three times as high in 1923.

| year | Cost of living index | Stock index of stat. Reich Office | 1 troy ounce of gold | 1 gold mark | 1 US dollar |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in paper mark | |||||

| 1913 | 100 | 100 | 86.81 | 1.00 | 4.20 |

| 1917 | 260 | 126 | 117.20 | 1.35 | 5.67 |

| 1918 | 337 | 88 | 171.15 | 1.97 | 8.28 |

| 1919 | 566 | 127 | 966.74 | 11.14 | 46.77 |

| 1920 | 1,158 | 274 | 1,508.91 | 17.38 | 73.00 |

| 1921 | 1.928 | 731 | 3,967.19 | 45.72 | 191.93 |

| 1922 | 68.506 | 8,981 | 156,870.21 | 1,807.83 | 7,589.27 |

| 1923 | 124,700,000,000,000 | 26,890,000,000,000 | 86,814,000,000,000.00 | 1,000,494,971,000.00 | 4,200,000,000,000.00 |

Great Depression

The global economic crisis began with the stock market crash on October 24, 1929, Black Thursday . The gold backing prevented the US Federal Reserve from expanding the money supply, which led to corporate collapses, massive unemployment and deflation . The deflation from 1929 onwards in Europe was triggered, among other things, by the fact that, due to declining gold reserves (it was only borrowed gold), associated banknotes were withdrawn and not reissued.

Another reason for the collapse of the economy was overinvestment in the agricultural and commodity markets. Since demand could not keep up with the increased supply, demand and prices began to fall. Contrary to the understanding of the economy at the time, there was no economic recovery after two to three years and a sharp fall in prices followed, which led to deflation. The prices of raw materials fell within three years by more than 60 percent, the prices for finished goods by more than 25 percent. Industrial production fell in the USA by around 50 percent and in Germany by around 40 percent.

On July 13, 1931, the collapse of the Darmstädter und Nationalbank (Danat Bank), the second largest bank in the country, triggered the German banking crisis . This was followed by two bank holidays and the changeover to foreign exchange management by emergency decree of July 15, 1931. Subsequently, almost all of the major banks were restructured with Reich funds and temporarily nationalized.

On 5 April 1933 signed US President Franklin D. Roosevelt , the Executive Order 6102 , after which the private ownership of gold was outlawed in the United States as of May 1, 1933 (see Gold ban ). As part of the Gold Reserve Act of January 31, 1934, the Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF) was established and the price of gold was raised to US $ 35.00. With the approval of the President, the ESF can act as a state stock exchange stabilization fund in the areas of gold, foreign exchange and other credit and securities instruments.

Investments versus deflation

Between 1927 and 1932, German stocks suffered real price losses of around 50 percent after adjusting for deflation. In April 1927, the stock index of the Reich Statistical Office , calculated for 329 stock corporations , reached a high of 178.02 points (base value 1924–1926 = 100 points). More than two years before the stock market crash in New York in October 1929, prices began to fall. The collapse of the Danat Bank led to the closure of the Berlin Stock Exchange from July 13, 1931 to September 2, 1931 . After reopening, the share index was determined to have a value of 56.96 points in September. Due to the crisis over the British pound, the exchange closed again from September 18, 1931 to April 11, 1932. In April 1932 the stock index number was 49.64 points, a nominal 72.1 percent lower than in April 1927. The slump had lasted 5 years, in autumn 1932 the prices rose again. By June 1941 the index rose to a high of 150.58 points.

Government bonds made slight gains from October 1929 to August 1931. After a brief slump, prices rose to pre-crisis levels by autumn 1932. Life insured remained largely protected. Most of their money was in interest-bearing securities, the price losses of which were only temporary. A run on the banks and the forced foreign exchange economy led to the freezing of savings deposits. Deflation counteracted the devaluations. State guarantees provided a slight reassurance. Property owners still had to pay the house interest tax introduced in 1924 , the tax rate of which fell over the years. Those who rented housing had a source of income even if they lost their jobs.

The gold parity was raised in 1934. At that time, the central banks were obliged to exchange the paper currencies they issued for gold at a fixed rate. The Reichsbank paid 147 Reichsmarks for 1 troy ounce of gold. The precious metal could not go bankrupt and appreciated by 70 percent in the global economic crisis.

Those who owned stocks in gold and silver producers made high profits. The prices of the American Homestake Mining Company (now part of Barrick Gold ) rose 737 percent on the New York Stock Exchange between 1929 and 1936 . The company also paid dividends of $ 171 during that period, more than twice its 1929 share price. Shares in Canadian Dome Mines Limited (now part of Barrick Gold) rose 921 percent in value. The price increase took place over the entire period of the deflationary period 1929 to 1933 and the onset of inflation from 1934 to 1936. The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell by 89 percent between 1929 and 1932. In 1936 the American stock index was still 62 percent below its 1929 level.

The table compares the prices and dividends of gold stocks with the development of the Dow Jones Index from 1929 to 1937.

| year |

Homestake mining | Dome mines | Dow Jones Industrial Average |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Share price | dividend | Share price | dividend | ||

| Low 1929 | 65 | 7.00 | 6.00 | 1.00 | 381.17 high |

| High 1930 | 83 | 8.00 | 10.38 | 1.00 | 157.51 low |

| High 1931 | 138 | 8.45 | 13.50 | 1.00 | 73.79 low |

| High 1932 | 163 | 10.60 | 12.88 | 1.30 | 42.22 deep |

| High 1933 | 373 | 15.00 | 39.50 | 1.80 | 50.16 deep |

| High 1934 | 430 | 30.00 | 46.25 | 3.50 | 85.51 low |

| High 1935 | 495 | 56.00 | 44.88 | 4.00 | 96.71 low |

| High 1936 | 544 | 36.00 | 61.25 | 4.00 | 143.11 low |

| High 1937 | 430 | 18.00 | 57.25 | 4.50 | 113.64 low |

Bretton Woods System 1944 to 1971

Introduction of the gold dollar standard

On April 22nd, 1944, the Bretton Woods system , named after the conference in Bretton Woods , a place in the US state of New Hampshire , was created, an international currency system based on the US dollar deposited with gold, and the US dollar as the world's reserve currency elected. The gold dollar standard took the place of the gold currency standard. The agreement stipulated an exchange ratio of $ 35 per troy ounce of gold. By orienting the exchange rates to the US dollar, the gold price could be fixed for a longer period of time. With the system, the US Federal Reserve was obliged to exchange the dollar reserves of each member country for gold at the agreed rate.

The aim of the agreement was the smooth handling of world trade free of trade barriers at fixed exchange rates. To ensure the functioning of the system, the World Bank , the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) were established. With the conclusion of the treaty, the central banks of the member states undertook to intervene in the foreign exchange markets to keep the exchange rates of their currencies within set limits. The Federal Republic of Germany joined the system of fixed exchange rates in 1949.

Currency reform in Germany

| date | Gold price per kg |

|---|---|

| June 15, 1939 | 2784 RM |

| Apr 29, 1941 | 3500 RM |

| Apr 1, 1948 | 3600 RM |

| Oct 25, 1948 | 3800 DM |

| Apr 1, 1949 | 4060 DM |

| Oct. 1, 1949 | 5120 DM |

| Nov 3, 1949 | 5030 DM |

| Sep 18 1953 | 4930 DM |

| June 13, 1954 | 4800 DM |

On June 20, 1948, the currency reform came into force in West Germany , and from June 21, the German mark (DM) was the sole legal tender . The Frankfurt Stock Exchange was closed for three weeks. When trading resumed on July 14, the first share prices for German standard values in D-Marks opened around 90 percent below their quotations in Reichsmarks.

Creditors of bonds lost more than 90 percent of their capital. Industrial bonds , Pfandbriefe and municipal bonds were traded in Reichsmarks at a fraction of their last rate. The conversion resulted in losses of 95 percent for life insurance owners . It was not until the early 1950s that the state returned part of their assets to the insured. With the currency reform of 1948, bank balances were converted into D-Marks at a ratio of 100 to 6.5 and debts at a ratio of 10 to 1. Savers thus lost 90 percent of their deposits and debtors had to bear around 90 percent less debt.

According to the Burden Equalization Act, property owners in West Germany had to pay half of their assets into an equalization fund as of June 21, 1948 in 120 quarterly installments, i.e. spread over 30 years. For this purpose, a property levy , a mortgage profit levy and a credit profit levy were introduced, which were payable to the tax authorities . Due to the long period of time, these burdens (0.6 percent per year) could be paid from the income of the asset concerned without having to attack the asset substance, although these benefits gradually became easier for those affected as a result of the constant inflation in the years 1948 to 1978 .

Investors who were able to save physical gold through World War II kept their fortunes. The gold price rose nominally by 84 percent between 1939 and 1949. The price index for the cost of living in all private households (consumer price index) grew by 66 percent over the same period.

The introduction of the D-Mark in the Western Zones threatened the Soviet Occupation Zone (SBZ) with a large inflow of Reichsmarks and thus inflation. For this reason, a currency reform was also carried out in the Soviet Zone on June 23, 1948 and the Deutsche Mark of the German Central Bank was introduced. Savings balances of up to 100 Reichsmarks were retained at a ratio of 1: 1, up to 1000 Reichsmarks at 5: 1 and up to 5000 Reichsmarks at 10: 1. Amounts over 5000 Reichsmarks were confiscated, as war or black market profits were assumed from the outset . Property owners were affected by expropriation . Gold ownership was not forbidden. Officially, however, there was no way to buy precious metals.

Since the GDR population could no longer travel to western countries after the construction of the Berlin Wall on August 13, 1961 and there was no foreign currency to purchase, gold bars and coins did not enter the country. Wedding rings and dental gold were only available against surrender of old gold. According to the GDR Precious Metals Act of July 12, 1973 (Journal of Laws I No. 33 p. 338), up to 10 grams of fine gold or 12 grams of dental gold or 5 tufts of gold leaf could be imported as gifts for personal use in cross-border gift parcels and small parcels become. The items were not allowed to be resold according to the customs regulations. If there were no western connections, precious metal rings were purchased on the black market or on vacation trips to the Soviet Union . Officially, a gold ring of up to 60 rubles (about 350 GDR marks) was allowed per person .

The overview compares the development of gold with the 30 largest German stock corporations and a selection of 21 interest-bearing securities (4 public bonds, 6 Pfandbriefe, 11 industrial bonds). The last RM rates before the currency reform and the first DM rates after the currency reform are listed (unweighted average in each case).

| Asset class | Last RM course |

First DM course |

Change in% |

|---|---|---|---|

| shares | |||

| Official courses | 161.78 | 30.53 | −81.13 |

| Black market rates | 305.68 | 30.53 | −90.01 |

| Interest-bearing securities | |||

| Public bonds | 154.25 | 12.25 | −92.06 |

| Bonds | 95.92 | 7.96 | −91.70 |

| Corporate bonds | 105.27 | 7.39 | −92.98 |

| Precious metals | |||

| Gold per kg | 3600 | 3600 | 0.00 |

Triffin Dilemma

In 1959, the economist Robert Triffin drew attention to a design flaw in the Bretton Woods system known as the Triffin dilemma . Due to the limited gold stocks, the liquidity required for global trade was only possible by releasing additional US dollars. But this created deficits in the US balance of payments . Triffin proposed creating an artificial currency in addition to gold and the US dollar. This was later realized in the form of the so-called Special Drawing Rights (SDR).

On October 3, 1969, the Board of Governors of the IMF decided to introduce SDRs. The new reserve medium should create additional liquidity for the international financial system. One SDR was originally equivalent to $ 35, the price of an ounce of gold. Therefore, the colloquial term was paper gold . Like physical gold, it could be used for payment at any time between central banks. But the special drawing rights came too late. The amount of dollars in circulation was already so great that the USA could no longer meet its obligation to redeem it in gold in an emergency. Since July 1, 1974, the SDRs are no longer tied to gold, but are calculated from a currency basket that contains the world's most important currencies.

London Gold Pool

In the years after World War II, American short-term external debt rose rapidly; as early as 1960, at $ 21.2 billion, they exceeded their national gold holdings of $ 18.7 billion (valued at $ 35 per troy ounce) for the first time. As a result, there were ever larger exchanges of the dollar for physical gold.

To maintain gold parity , a gold pool was agreed on November 1, 1961 in London between the central banks of Belgium, the Federal Republic of Germany, France, Great Britain, Italy, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the USA. The participating countries undertook to keep the gold price at a certain level through market intervention. The states paid 1.08 billion Deutsche Mark gold (Federal Republic: 119 million Deutschmarks) into the coffers according to a fixed quota system. As soon as the supply was used up, the members of the sales consortium had to pay in gold according to their quota.

| member | proportion of | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| in % | in USD million | in tons | |

| US Federal Reserve | 50 | 135 | 120 |

| German Bundesbank | 11 | 30th | 27 |

| Bank of England | 9 | 25th | 22nd |

| Banque de France | 9 | 25th | 22nd |

| Banca d'Italia | 9 | 25th | 22nd |

| Belgian National Bank | 4th | 10 | 9 |

| De Nederlandsche Bank | 4th | 10 | 9 |

| Swiss National Bank | 4th | 10 | 9 |

Crisis and collapse

In June 1967 Charles de Gaulle declared that the Vietnam War made it impossible for France to continue to support the US dollar through the London gold pool. When the British government decided on November 18, 1967 to devalue the pound, at that time the most important reserve currency after the US dollar, a rush for gold began at the London Bullion Market .

On March 17, 1968, the representatives of the central banks involved in the London gold pool met in Washington, DC , where they decided to end gold interventions and signed an agreement to split the gold market in two. One price could freely adjust to the market, the other was fixed. After two weeks of closure, the London gold market reopened on April 1, 1968. The first gold fixing was found to be US $ 38.00 per troy ounce (15.81 pounds sterling).

In 1969, several participating states from the Bretton Woods Agreement wanted to redeem their dollar reserves in gold. However, the US was unable to meet its contractual obligations. As a result, the dollar could no longer fulfill its function as a reserve currency . On August 15, 1971, the American President Richard Nixon declared that the dollar could no longer be exchanged for gold.

The amount of dollars in circulation by the US central bank up to this point and accumulated abroad due to a foreign trade deficit was so great that the US gold reserves would not have been sufficient to redeem the dollar holdings of a single member state in gold: short-term foreign liabilities of 40.7 In 1971 there were only 10.2 billion dollars in American gold reserves. With the end of the gold price peg to the dollar, the artificially fixed gold price of $ 35 per troy ounce was history.

Gold in paper currency

Upward trend from 1971 to 1980

On May 1, 1972, the price of gold rose above the $ 50 mark for the first time since 1864, at $ 50.20 per troy ounce. Adjusted for inflation, at that time 306.1 US dollars per troy ounce had to be paid.

After strong monetary policy turbulence and a fortnightly global currency market shutdown, the Bretton Woods Agreement was in fact replaced on March 19, 1973 by a system of flexible exchange rates without being linked to gold or dollars. Several states of the European Economic Community (EEC) finally gave up their policy of support against the dollar and founded the European exchange rate union .

On May 14, 1973, the price of gold in London exceeded the US $ 100 mark for the first time at US $ 102.25 (US $ 587.03 adjusted for inflation). On November 14, 1973 the price of gold was released and on December 31, 1974 President Gerald Ford signed a law that legalized the possession of gold in the United States again.

On 7./8. On January 1st, 1976, the Interim Committee of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) met in Kingston , Jamaica , and reached an agreement on the gold standard and the international exchange rate system . With the signing of the Jamaica Agreement, the de jure exchange rates were released. The binding of parities to gold was excluded. Since then, the national currencies have been pure, manipulated paper currencies. They are no longer covered by gold and can theoretically be increased as required, although the actual money supply is normally controlled by independent state central banks today. It is no longer possible to exchange cash for gold or currency reserves.

In the 1970s, stagflation prevailed in the industrialized countries with high inflation, weak economic development, low productivity and high unemployment. This period was characterized by great uncertainty in the financial world, the oil crisis , a sharp rise in the US national debt , a massive expansion of the (paper) money supply and a flight of capital investors into real assets. The price of gold grew fifteen times during this time.

On December 27, 1979, the price of gold passed the $ 500 mark for the first time at $ 508.75 ($ 1,788.87 when adjusted for inflation). On January 21, 1980, the price of gold on the London Bullion Market reached a record high of $ 850.00 per troy ounce (adjusted for inflation: $ 2,632.81) in view of the crisis in Iran and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan . During trading on the New York Commodities Exchange (COMEX), a high of 873.00 US dollars was achieved (inflation-adjusted: 2,704.05 US dollars). The nominal all-time high marks the end of a ten-year upward trend and lasted for 28 years.

There are several highs for the gold price in January 1980, depending on which trading venue or which calculation basis is selected.

| price | date | Trading center | description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 834.00 | Jan. 21, 1980 | New York Commodities Exchange | Closing price on the futures market (February future) |

| 850.00 | New York Commodities Exchange | Trading history on the spot market | |

| 850.00 | London Bullion Market | Gold fixing | |

| 873.00 | New York Commodities Exchange | Trading history on the futures market (February future) | |

| 885.60 | Jan. 17, 1980 | Chicago Board of Trade | Trading history on the futures market (February future) |

Downward trend from 1980 to 2001

In 1980 the gold price began a twenty year downward trend. In order to end the economic stagnation, the US Federal Reserve took other measures to limit the growth of the money supply . This initially intensified the recession and unemployment, but these policies slowly stabilized the economy and controlled inflation. In the 1990s, under the Democratic President Bill Clinton (1993–2001) , the USA experienced a sustained economic upswing (“ New Economy ”). On August 3, 1994, the COMEX was merged with the "New York Mercantile Exchange" (NYMEX). On July 20, 1999, the gold price in London hit a low of 252.80 US dollars (387.2 US dollars adjusted for inflation).

In order to regulate gold sales and thus the gold price, 15 European central banks (including the Deutsche Bundesbank ) concluded the Central Bank Gold Agreement on September 26, 1999 in Washington D.C. , in which the volume of gold sales was regulated. The first gold agreement CBGA I (1999-2004) set the limit for gold sales to 400 tons (12.9 million troy ounces) per year (beginning on September 27) or a maximum of 2000 tons (64.5 million troy ounces) within five years firmly. The second agreement, CBGA II (2004–2009) allowed a maximum sales volume of 500 tons (16.1 million troy ounces) per year. In the third agreement, CBGA III (2009-2014), a maximum sales volume of 400 tons per year was agreed.

In the People's Republic of China , the private ownership of gold was banned in 1949 (see gold ban ). All gold had to be sold to the Chinese People's Bank . The central bank took over the monopoly on precious metals trading. Private individuals were excluded from trading in gold or silver. In 1981 the central bank decided to issue a gold coin for investment purposes. The elaborately minted gold panda has been issued annually with a fineness of 24 carats (999.9 ‰) since 1982 . On September 1, 1982, private individuals were allowed to purchase gold jewelry for the first time in more than 30 years. On June 15, 1983, the state legalized private gold and silver ownership. The trade in precious metals remained forbidden for the population.

In 1993 the Chinese People's Bank abandoned the determination of a fixed price and let the gold price float . In 2000 the government decided to establish a regular gold market, and in 2001 the central bank gave up its monopoly on gold trading. With the establishment of the Shanghai Gold Exchange on October 30, 2002, gold trading was expanded significantly and demand was stimulated. The trade ban for private investors has been lifted. In the next five years, China overtook the US and became the second largest customer after India .

Upward trend from 2001 to 2012

The gold price has been rising continuously since 2001. There is a correlation between its rise, the growth of US national debt and low US dollar exchange rates against other world currencies. Growing demand caused the gold price to rise above the $ 500 mark for the first time since 1987. On March 13, 2008, the price of gold on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) rose above the $ 1,000 mark for the first time during trading.

In September 2008, the real estate crisis caused the US government to take control of the two largest mortgage lenders in the US, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac . There were price falls on the global stock markets. Because bad loans were resold ( securitization ) and they were scattered all over the world, the crisis spread globally due to the close interlinking of individual economies and financial flows. The financial crisis subsequently affected the entire western world and also the economies that depend on it, such as China. After the bankruptcy of the fourth largest investment bank Lehman Brothers and the nationalization of the largest American insurer AIG , the gold price had its highest daily gain in history on September 17, 2008 in New York. In the course of trading it rose by US $ 92.40 or 11.8 percent to temporarily US $ 872.90.

On March 25, 2011, the US state of Utah introduced gold and silver coins as the official currency alongside the US dollar . With the signing of the "Utah Legal Tender Act" by Governor Gary Herbert , the law became final. On March 4, 2011, the House of Representatives in Utah approved the bill, and on March 15, the Senate. Similar legislative initiatives were submitted for review in a further 12 US states (as of March 2011).

On April 19, 2011, the gold price in New York was higher than 1500 US dollars per troy ounce for the first time during trading. The sovereign debt crisis in the euro zone , doubts about the US creditworthiness and the protests in the Arab world were the main contributors to the increase. Other reasons were the Tōhoku earthquake in Japan (March 11), which led to worldwide production stoppages and delivery problems, as well as the growth in world debt. According to the credit report of the World Economic Forum and McKinsey, at the end of 2010 the debt of governments, companies and households was 116 trillion US dollars, 104 percent higher than 10 years earlier. The debt ratio in relation to global gross domestic product (GDP) was 184 percent. An average interest rate of 5 percent resulted in an annual interest burden of $ 5.8 trillion.

The physical demand for gold bars and gold coins has been high since the outbreak of the financial crisis in 2007 and the sovereign debt crisis in the euro area in 2009. There were also strong inflows into exchange-traded funds (ETFs, a type of listed fund). The holdings of the world's largest gold-backed ETF, the SPDR Gold Trust , reached an all-time high on December 7, 2012 at 1,353.35 tons. This made the fund, whose deposits are managed by the Bank of New York Mellon and whose holdings are in a HSBC vault in London, the sixth largest gold holder in the world , behind France and ahead of China . Gold purchases from central banks, primarily in Asian countries, increased. Among the 32 countries with more than 100 tons of gold reserves (as of 2012), some have increased their gold reserves significantly since 2000: Mexico (1504%), China (167%), Turkey (155%), Russia (144%), Saudi Arabia ( 126%), Thailand (107%), Kazakhstan (83%) and India (56%).

On 6 September 2011, the price of gold rose in New York at an all time high of 1920.65 dollars per troy ounce. In the European common currency, a record price was achieved on October 1, 2012 at 1,388.62 euros per troy ounce. The value of gold in Swiss francs reached a historic high on October 4, 2012 at 1679.43 Swiss francs per troy ounce. All three currencies fell to an all-time low against gold. Investors were worried about the public finances of numerous countries (see e.g. euro crisis ), about the sustainability of the economic recovery and rising inflation. The measures taken by governments and central banks in the fight against the global economic crisis or banking and financial crisis implied growing public debt and a low interest rate policy . The global government debt rose, according to the British business magazine The Economist (ie 145 percent = average by 9.4% per year) 2002-2012 of about 20 trillion to 49 trillion US dollars. Investors fear (te) n because of the expansion of the money supply by the central banks a currency devaluation . Strong demand for jewelry, especially from the People's Republic of China and India, as well as purchases by institutional investors contributed to a record high for the gold price.

Decline in 2013 and subsequent sideways trend

At the beginning of April 2013, the price of gold fell significantly: on April 12, 2013, the price for a troy ounce (31.1 grams) on the New York Commodities Exchange NYMEX fell just below the $ 1,500 mark for the first time, reaching its lowest level since July 2011 2013 the gold price ended just above the US $ 1,200 mark. Since then, the price has been trending sideways around a value of around US $ 1,250, sometimes with significant fluctuations to around US $ 1,051 (Dec. 2015) and US $ 1,363 (Jul. 2016). At the end of 2017, the price was just under $ 1,300. Since mid-2019, the price of gold has risen more significantly again and marked a high in euros at more than 1,516 euros per ounce, although the price in US dollars has also risen at around 1,636 dollars, but is still far from previous highs. New highs were hit above $ 2048 on August 5, 2020.

Gold market

Market mechanisms

| year | Percentage ownership % |

|---|---|

| 1968 | 4.80 |

| 1980 | 2.77 |

| 2000 | 0.20 |

| 2001 | 0.20 |

| 2002 | 0.24 |

| 2003 | 0.26 |

| 2004 | 0.28 |

| 2005 | 0.29 |

| 2006 | 0.36 |

| 2007 | 0.39 |

| 2008 | 0.55 |

| 2009 | 0.57 |

| 2010 | 0.70 |

| 2011 | 0.96 |

Gold demand and supply often fluctuate. The price of gold rises or falls depending on the relationship between supply and demand and the price elasticity of demand and price elasticity of supply . Sometimes it is very volatile (= fluctuates considerably within a short period of time). The price of gold has been determined in US dollars for decades.

The gold price and dollar price tend to be inversely proportional; In other words: if the dollar rate falls, the gold rate often rises (and vice versa). For many buyers and sellers, gold is an object of speculation: they do not buy the gold because, for example, they buy it. B. need for jewelry production, but with the intention or hope to make a profit on a later sale. In addition, some investors see a "safe haven" in buying gold, especially in times of crisis.

The price of gold can be significantly influenced by market participants with large gold reserves , such as central banks and gold mining companies. If the gold price is to fall, gold is lent ( to provoke short sales ) or sold, and / or gold production is increased. If the gold price is to rise, the central banks buy gold or the gold production of the mining companies is throttled.

The total gold holdings of all central banks at the end of 2009 corresponded to only 16.2% (26,780 tons) of the gold available worldwide. This relativizes the possibilities of a gold-owning central bank to influence the course in their favor.

The total amount of gold ever mined was estimated at around 165,000 tons (5.3 billion troy ounces) in 2009. This corresponds to a theoretical market value of currently 10,390 billion US dollars. A price of 1,958.55 US dollars per troy ounce was taken as a basis (gold price as of August 3, 2020). For comparison: the market value of all bonds worldwide is 91,000 billion US dollars, the value of all derivatives 700,000 billion US dollars. The global gross domestic product in 2009 was, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) at 58,000 billion dollars.

The share of gold in global financial assets fell from 4.8% in 1968 to 0.2% in 2000. In the course of the bull market from 2001 onwards, the gold ratio increased. At the end of 2011, the value of gold available for investment (that is, excluding the jewelry industry, industrial applications, central bank currency reserves) was $ 2,000 billion. That corresponded to about 0.96% of the world's financial assets.

The share of international gold reserves in total currency reserves has fallen in the last three decades due to sales and less importance for currency hedging from 60% in 1980 to a low of 8.6% in March 2005. In September 2010 the share was back at 10.1%.

In times of war, the demand for gold falls and with it the price. Hunger and the impoverishment of the population lead to increased sales. Gold is often viewed as a long-term investment. This is especially true in times of crisis and hyperinflation . When stocks, funds and real estate values expire, the price of gold rises. Money becomes less valuable in such times of crisis because it is mass produced by the central banks to keep the economy going. Gold, on the other hand, cannot be artificially reproduced and thus becomes its own currency. The price detaches itself from supply and demand, a symbol of the increased distrust in governments and paper money .

Today, financial derivatives ( futures , forwards , options , swaps ) have an increasing influence on the gold price . Due to arbitrage transactions, in which traders use price differences at different financial centers to generate profits, these futures transactions have a direct influence on the price of gold for immediate delivery ( spot market ). In the USA in 2010/11 there was a strong concentration of commercial contracts (contracts) on the books of a few major American banks on the commodity futures market. On the silver market, where similar market structures prevail, a lawsuit was brought against JPMorgan Chase & Co. and against the US branch of the British bank HSBC in October 2010 for alleged silver price manipulation.

Trading venues

For standardized gold trading on commodity exchanges , “ XAU ” was assigned as a separate currency code according to ISO 4217 . It denotes the price of one troy ounce of gold. XAU is the currency abbreviation published by the International Organization for Standardization , which is to be used for clear identification in international payment transactions . The "X" indicates that this is not a currency issued by a state or confederation of states.

The international securities identification number is ISIN XC0009655157. The Bloomberg ticker symbol for the spot market price for gold is GOLDS <CMDTY>.

The most important trading venues for gold futures and gold options are the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) and the Tokyo Commodity Exchange (TOCOM).

The London Bullion Market is the center of physical trading in gold bars , known as over-the-counter (OTC) trading . Its customers are mainly institutional investors. Only bars from refineries and mints that meet certain quality requirements are permitted for trading . The international seal of approval "good delivery" (German: "in good delivery") guarantees the embossed or stamped features such as fineness and weight. Gold bars with good delivery status are accepted and traded worldwide.

Other marketplaces for the physical trading of gold bars are New York, Zurich and Hong Kong.

On the spot market prices are traded for immediate physical delivery, while fixed to the futures and options markets prices for deliveries in the future. The spot price and the future price usually develop in parallel.

Shares of international gold producers who do not trade or sell their gold production on the futures exchanges are listed in the NYSE Arca Gold BUGS Index (HUI, formerly AMEX Gold BUGS Index). The index is calculated on the NYSE Amex (formerly American Stock Exchange). The Philadelphia Gold and Silver Index (XAU) comprises both hedged and unhedged gold and silver producers . Index trading takes place on the NASDAQ OMX PHLX , formerly the Philadelphia Stock Exchange (PHLX).

Largest gold exchanges

The Chinese Gold and Silver Exchange Society (CGSE) was the first stock exchange in Hong Kong to be incorporated into law in 1918 . As the "Gold and Silver Exchange Company", it had been trading physical gold since 1910 under various rules and guidelines. In 1974, trading in gold futures began on the New York Commodities Exchange (COMEX), the world's largest gold exchange . COMEX was founded in 1933 and merged with the "New York Mercantile Exchange" (NYMEX) in 1994. The following table contains the largest gold exchanges on which the gold price is traded according to the "World Gold Council".

| rank | Surname | acronym | country | opening |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | New York Mercantile Exchange 1 | NYMEX | United States | Dec. 31, 1974 |

| 2. | Tokyo Commodity Exchange | TOCOM | Japan | 23 Mar 1982 |

| 3. | Chicago Board of Trade 2 | CBOT | United States | Feb. 20, 1979 |

| 4th | Istanbul Gold Exchange | IPI | Turkey | July 26, 1995 |

| 5. | Multi Commodity Exchange of India | MCX | India | Nov 10, 2003 |

| 6th | National Commodity and Derivatives Exchange | NCDEX | India | Dec 15, 2003 |

| 7th | Shanghai Gold Exchange | SGE | China | Oct 30, 2002 |

| 8th. | Turkish Derivatives Exchange | TurkDEX | Turkey | Feb 4, 2005 |

| 9. | Dubai Gold & Commodities Exchange | DGCX | UAE | June 28, 2005 |

Trading hours

There are two sessions at the Tokyo Commodity Exchange (TOCOM):

Day session: Monday to Friday 9:00 am to 3:30 pm JST (1:00 am to 7:30 am CET )

Night session: Monday to Friday 5:00 pm to 11:00 pm JST (9:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. CET)

The following trading hours apply at the London Bullion Market :

Monday to Friday 8:50 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. UTC (9:50 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. CET) a price is determined

twice a day for the gold fixing :

Morning: 10:30 a.m. UTC (11 : 30 p.m. CET)

Afternoon: 3 p.m. UTC (4 p.m. CET)

Trading on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) takes place at the following times:

Floor: Monday to Friday 8:20 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. EST (2:20 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. CET)

Electronic (CME Globex): Sunday through Friday 6:00 p.m. to 5:15 p.m. EST (12:00 a.m. to 11:15 p.m. CET)

Gold fixing

The price of gold has been determined at the London Bullion Market since the 17th century. From September 12, 1919, gold dealers met at 10:30 a.m. local time (11:30 a.m. CET) in a Rothschild bank on St. Swithin Lane in London to formally fix the gold price. The five founding members were NM Rothschild & Sons , Mocatta & Goldsmid , Samuel Montagu & Co., Pixley & Abell and Sharps & Wilkins . Since April 1, 1968, there has been another daily meeting in London at 3:00 p.m. local time (4:00 p.m. CET) to set the price again when the US stock exchanges are open.

In April 2004 NM Rothschild & Sons withdrew from gold trading and gold fixing. Since May 5, 2004 the gold price has been set by telephone. As of June 7, 2004, the meeting, which was previously chaired permanently by Rothschild, will take place at Barclays Bank under an annual rotating chairmanship. Since March 20, 2015, the composition of the LBMA has been expanded considerably. One of the five original institutions, Deutsche Bank AG London , withdrew from the gold business after it was proven that it had manipulated the gold price. At this event (as of 2017) one representative of the

- Bank of China Limited ,

- Barclays Bank PLC ,

- Goldman Sachs International ,

- HSBC Bank USA NA London Branch ,

- JP Morgan ,

- Morgan Stanley

- Bank of Nova Scotia – ScotiaMocatta ,

- Société Générale ,

- Standard Chartered Bank ,

- Toronto-Dominion Bank (TD) and the

- UBS Group AG ,

who are all members of the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA).

manipulation

In the realm of speculation belongs the rumor that the US Federal Reserve (Fed) is manipulating the gold price in cooperation with credit institutions . According to this theory, a low gold price is wanted by the US government , as this strengthens confidence in the US dollar, the paper currency. A high gold price is said to reflect the weakness of the monetary currency. The claim that the US Federal Reserve would be interested in low gold prices can only be substantiated economically to a limited extent.

The following monetary policy reasons speak in favor of suppressing the gold price of the US Federal Reserve: A rising gold price is an expression of an inflationary development, whereby the population has the expectation that paper money will continuously decrease in value. High inflation expectations hamper the primary monetary policy objective of ensuring the stability of the currency. In addition, a falling gold price leads to falling interest rates. It reduces the attractiveness of gold investments compared to investments in fixed income securities . Finally, a declining gold price strengthens the US dollar, which alongside gold is the number one reserve currency for foreign central banks. The US has fewer problems financing its budget and current account deficits if foreign central banks do not have an attractive alternative to the dollar.

The following reasons speak against an intervention by the US Federal Reserve: The largest player in the gold market is the jewelry industry, which in 2010 had a share of 54 percent of global gold demand . The largest gold holdings are in private hands. For example, it is estimated that around 20,000 tons of gold are privately owned in India . The gold price thus reflects a highly complex market. Since the US Federal Reserve itself has by far the largest public gold reserves in the world, the US government is more interested in the highest possible gold price. Ultimately, a falling gold price devalues their own holdings. The higher the gold price, the more it can achieve with its own emergency supplies.

For years, market participants have suspected that gold and silver prices will be depressed by large short positions. There have been noticeable price anomalies on the gold market since 1993. The most frequent times are the opening of the NYMEX commodities exchange in New York at 2:20 p.m. CET and the afternoon fixing in London at 4:00 p.m. CET. At this time there are often drops in the gold price and sharp price movements in other markets within a few minutes. An interest group consisting of the Fed, the US government, gold trading banks (Bullion Banks) and the IMF are said to be responsible for suppressing the gold price. In this context, critics also speak of the so-called gold cartel. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), an independent agency in the United States that regulates the futures and options markets in the United States, has confirmed that there has been manipulation of the silver market. In 2010, CFTC Commissioner Bart Chilton said: "There have been fraudulent attempts to move the price and control it in insincere ways."

Gold ban

A so-called gold ban is usually issued by governments when states are in a currency crisis . It means a private trade and possession ban for the precious metal gold. Private individuals have to hand over their gold (coins, bars, nuggets, certificates) to state acceptance points and exchange them for paper money. You are only allowed to own gold in the form of jewelry and minted coin collections. Exceptions exist only for industries in which the precious metal is used, such as jewelers, artisans and dentists.

Gold ownership bans are usually associated with criminal or regulatory threats of sanctions. As interference with the fundamental right to property, they are subject to special legality requirements . Possession bans are usually not very effective, as many private individuals do not declare or do not deliver their gold holdings. Where gold ownership is prohibited, either gold smuggling flourishes, which supplies the black markets - for a corresponding premium - or the citizens buy the gold abroad.

In history there have been prohibitions and restrictions on private gold and silver ownership in all social systems , from classical antiquity through medieval feudal society to the socialist states and developing countries of modern times . They existed not only in totalitarian dictatorships , but also in democratic countries . Examples of this are the Weimar Republic in the interwar period in 1923, the USA in 1933 and France in 1936, and in the post-war period India in 1963 and Great Britain in 1966. In 1973 private gold ownership was still subject to restrictions in over 120 countries around the world . In connection with the end of the Bretton Woods system , most of the restrictions were lifted. The gold bans in many socialist countries remained in place. They were only overridden two decades later with the economic collapse of the Eastern Bloc .

Gold investment

Investment opportunities

Investing in gold can be done through physical purchases and securities trading. Gold bars and investment coins can be purchased from banks, precious metal and coin dealers. There are rental and insurance costs for storage in a bank safe. In contrast to bars and coins made of silver , platinum and palladium , the purchase of gold bars and gold coins in Germany is exempt from sales tax, provided that the gold bars and gold coins qualify as investment gold according to Section 25c (2) of the Sales Tax Act (UStG).

Investors can invest in certificates , funds or exchange-traded funds (ETFs) directly via the stock exchange or broker . There is no physical delivery here. Certificates are dependent on the solvency of the issuer and influence the demand situation on the commodity exchanges indirectly via the banks' hedge transactions (Certificate → Future → Spot ).

It is also possible to buy a no-par value bond denominated in gold, the so-called Xetra-Gold . The bond is a security in the form of a bearer bond that certifies a right to the delivery of gold. Trading takes place on the electronic trading system Xetra of Deutsche Börse .

In addition, buying shares in gold mining companies offers the prospect of higher returns in the form of price increases and dividends than investing in the physical precious metal. However, these investments also contain higher risks, such as production stoppages due to the collapse of tunnels, management errors, strikes, higher credit burdens or capital increases after liquidity bottlenecks, political influence and bankruptcy , which are reflected in significant price fluctuations due to the tight market. Like almost all shares, shares of gold mining companies are also suitable for an impending inflation , as they certify a share of the company's real capital, i.e. the shareholder owns a share of the gold that is still in the ground.