Former state insane asylum in Heppenheim

Coordinates: 49 ° 38 ′ 6 ″ N , 8 ° 38 ′ 36 ″ E The state insane asylum in Heppenheim is a former psychiatric clinic on the southern outskirts of Heppenheim (Bergstrasse) in the state of Hesse . The complex on Ludwigstrasse will be called The Bergstrasse Sports & Country Club from 2015 after it has been converted into condominiums. The twelve individual buildings are located in the middle of the Heppenheim arboretum . The castle-like central assembly, the bowling alley, the former gate and isolation houses were built between 1861 and 1892 in the classicism style and are under monument protection .

history

Foundation and "role model for Germany"

Around 1850 the Grand Duchy of Hesse only had one psychiatric clinic , the Philipp Hospital in Hofheim near Riedstadt . Its buildings were in poor condition and did not offer the facilities that contemporary psychiatry needed to treat the mentally ill. Therefore, in 1857 , the state estates commissioned the Hofheim clinic director Georg Ludwig (1826–1910) to design a new hospital at a different location. The choice fell on Heppenheim, probably because of its convenient location and the charming landscape on Bergstrasse . Georg Ludwig planned the clinic in collaboration with the architects Christian Friedrich Stockhausen (1799–1870), Friedrich Obenauer (1825–1905) and Paul Amelung (1823–1868). Construction began in 1861 and was completed by the end of 1865. The first patients (of both sexes) were admitted on January 2, 1866. Georg Ludwig took over the management.

For the time, the clinic was a progressive psychiatric facility. In professional circles she enjoyed the reputation of being a "role model for Germany" in terms of architecture, furnishings and surroundings. As a former representative of treatment without coercive measures , director Georg Ludwig avoided restraint or corporal punishment as much as possible . In the spirit of Ferdinand von Ritgen , Ludwig viewed mental illnesses as ailments of the brain, which - similar to a broken arm - could be treated or at least alleviated through rest and moderate stimulation. In keeping with the unit psychosis theory, attempts were made in Heppenheim to keep patients away from anything that could trigger melancholy ; because this was considered the basis of all mental illnesses. The building and garden should form the appropriate environment for this. The classical architecture represented the opposite pole to the mental chaos of the occupants through the order, symmetry and brightness of the rooms. The rooms were equipped with large windows that let in plenty of daylight and afforded a view of the garden . This offered a great wealth of tree species, leaf colors and scents. Bowling alleys , boules and gardening were all recreational activities.

Expansion and realignment

Since the number of inmates grew steadily, the clinic had to be expanded extensively between 1866 and 1892. The patient wings were raised several times; In 1872 two isolation houses were built in the east of the property, in which patients with rage or contagious diseases were housed for a limited time.

Under the direction of Heinrich Adolf Dannemann , the institution introduced occupational therapy in the 1920s . As a result, a pig and chicken coop and other buildings for agriculture, horticulture and livestock were built.

time of the nationalsocialism

Like almost all psychiatric facilities in the German Reich , the Heppenheim Clinic was also affected by crimes of Nazi racial hygiene . Starting in 1934, an unknown number of inmates were forcibly sterilized . In 1940 " Aktion T4 " reached the clinic: at least 59 men and women were killed in the Hadamar killing center . 24 Jewish patients were murdered in the Brandenburg killing center ; the fate of 67 others is unknown.

The hospital was practically depopulated in 1941 after the deportation . The Wehrmacht then misappropriated the building as a hospital for prisoners of war. While the French prisoners received adequate care, the Soviet prisoners were deliberately neglected due to racial reservations. 385 died from their injuries and the inhumane conditions of detention. You are buried today in the military cemetery in Auerbach near Bensheim .

Since the 1990s, a plaque has been commemorating the victims of National Socialism in the Heppenheim clinic. It has been located at the new location next to the district hospital since 2014. The current owner, the Nuremberg-based terraplan group, is planning to set up a new memorial site on the old clinic premises as part of the renovation.

New beginning after the Second World War

At the end of World War II in April 1945, the US Army captured Heppenheim and freed the prisoners of war. For a short time the occupiers used the clinic itself as a hospital. In 1945 some of the buildings were converted into a prison for politically accused persons as part of the denazification process ; The US Army accommodated displaced persons in the other buildings .

After the end of external use, the psychiatric clinic was able to resume its work in 1948; the newly founded State Welfare Association of Hesse took over the sponsorship in 1953 . In the 1960s, current reforms in the field of psychiatry were implemented in Heppenheim, giving patients more self-determination and freedom. The bars on the windows were removed, new common rooms were created and the park, which had been closed until then, was made accessible to the public. In 1987 the hospital management lifted the gender segregation . On the part of the property to the east of the main building, several new buildings - ballroom, chapel and laundry - were built in the 1950s .

Conversion to a residential complex

Due to a lack of space and high maintenance costs, the operating company of the Vitos Heppenheim clinic decided in 2008 to give up its location on Ludwigstrasse. Since 2010, a new building has been built next to the district hospital according to plans by the Frankfurt office Witan Ruß Lang Architects . The move was completed in September 2014.

In 2014, the real estate company terraplan from Nuremberg , represented by Erik Roßnagel, acquired the site of the old clinic on Ludwigstrasse. The client is planning to renovate the listed buildings and convert them into a residential complex under the name The Bergstrasse Sports & Country Club . 180 condominiums are to be built in three construction phases . Fitness studio , wine cellar and barbecue area will become part of the sports and common areas for future residents. The gate houses at the entrance to the west are to house businesses in the future. The renovation planning for the building is in the hands of the Berlin architect Uwe Licht from raumwandler.de . Work on the first construction phase (the northern wing) is scheduled to begin in November 2015 or, depending on the weather, in the first quarter of 2016. With regard to their topographical surroundings, the main buildings of the complex are given the new names Starkenburg wing (north wing), Maiberg wing (administrative and commercial building) and Weingarten wing (south wing).

The former ballroom with the “Zum Eckweg” café is currently being used by a new tenant. In the long term, the buildings erected after 1945 in the eastern part of the property are to be replaced by five apartment buildings with 65 additional condominiums. The two former isolation houses in the south and north-east of the facility are under monument protection and will be preserved.

Plant and architecture

In the interplay of architecture , garden art and their integration into the environment, the clinic buildings erected between 1861 and 1892 form a total work of art of classicism . Its design is the result of cultural-historical developments, theories of psychiatry , architecture and horticulture from around 1860. Yellow and red sandstone from the area around Heppenheim were used for the construction .

Idol

The model and inspiration for the functional planning of the clinic were the Illenau asylum and the tracts of the clinic director there, Christian Friedrich Wilhelm Roller . Like Illenau, the clinic in Heppenheim was built outside the urban development and integrated into the natural and cultural landscape of Bergstrasse . The Erbach provided fresh spring water; the heights of the vinegar ridge in the east provided natural protection against wind and weather. According to contemporary psychiatry and ideas about hygiene, the connection between therapy room and nature is the ideal setting for the treatment of mental illnesses.

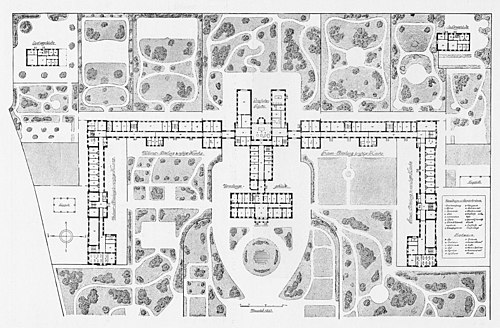

The gender-separated patient houses with an L-shaped floor plan were arranged in the north and south of the administration and farm building. While the quiet patients moved into rooms close to the administration building, the noisy and maddened patients were accommodated in the distant parts of the wing. This should ensure that the noisy inmates disrupt the clinic as little as possible. The doctors were nevertheless able to get to the raging patients quickly in an emergency via the courtyard.

park

The park with recreational and communal areas for the inmates, which surrounds the clinic buildings, was planted in the manner of contemporary city parks and villa gardens with local and exotic trees, shrubs and flowers. As a section of nature bounded by walls, it originally served to relax and amuse the patients. As part of the renovation from 2015, the park will be repaired by the garden planning office Oehm & Herlan from Nuremberg. In future it will also be open to the public as a tree park ( arboretum ). At the beginning of 2015 a book was published that explains the history and botanical characteristics of the arboretum to future visitors.

Design as a lock

The main buildings and gate houses are arranged symmetrically and designed in mirror image. The center of land and buildings is the administration building as a Corps de Logis is. His middle buttress with staircase and balcony is the Point de vue of the driveway of the Ludwig street. The two patient houses with their L-shaped floor plan border the western part of the arboretum like a courtyard . The extensive park with exotic plant species, the symmetry of the buildings and the design of their facades in the style of ancient Greece give the entire complex the appearance of a castle.

The castle-like design of public facilities (especially government buildings, museums, universities and hospitals) is typical of architecture around the mid-19th century. In the course of the century, the bourgeoisie had been able to secure more and more political participation through revolutions and reforms - also in the Grand Duchy of Hesse , which was converted into a constitutional monarchy in 1820 . By adopting aristocratic forms of construction, the bourgeoisie gave expression to their claim to power. In Heppenheim, the character of the “hospital castle [es]” was particularly strikingly accentuated by the pronounced symmetry of the buildings and the lavish garden design with driveway and courtyard.

Rehabilitation of the historical buildings

As part of the renovation from 2015, the listed buildings are to be brought back to their original condition. The subsequent connecting corridors between the former administration building and the patient wings will be demolished so that the three buildings will be free again. According to the client, Terraplan, the original division of the windows will be restored. Some of the façades are to be provided with balcony porches ; dormers and terraces are planned behind the sandstone eaves on the top floors . According to a plan by the Berlin interior designer Eugen Gehring, the vaulted cellars will house various common areas such as a fitness studio , sauna and wine cellar .

Photo gallery

Window on the administration building with historical blind saddle cloth

South wing with a view of the Heppenheim arboretum on Bergstrasse

See also

literature

- Adolf Heinrich Dannemann : The development of care for the mentally ill in the Grand Duchy of Hesse . In: Johannes Bresler (ed.): German sanatoriums and nursing homes for the mentally ill in words and pictures . 1st edition. Carl Marhold, Halle (Saale) 1910, p. 142-143 .

- Peter Eller: Georg Ludwig and the establishment of the “Grand Ducal State Insane Asylum” in Heppenheim . In: Psychiatry in Heppenheim. Forays into the history of a Hessian hospital 1866–1992 (= historical series of publications by the State Welfare Association of Hesse. Sources and studies ). 1st edition. tape 2 . Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen , Kassel 1993, ISBN 3-89203-024-3 , p. 10-25 .

- Peter Eller: The older building history . In: Psychiatry in Heppenheim. Forays into the history of a Hessian hospital 1866–1992 (= historical series of publications by the State Welfare Association of Hesse. Sources and studies ). 1st edition. tape 2 . Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen , Kassel 1993, ISBN 3-89203-024-3 , p. 26-35 .

- Dieter Griesbach-Maisant: Bergstrasse district (= cultural monuments in Hesse . Volume 1 : The cities of Bensheim, Heppenheim and Zwingenberg ). Theiss, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 978-3-8062-1905-0 , pp. 670-672 .

- Sebastian Gulden: Garden for the soul . In: Erik Roßnagel, Stefanie Egenberger, Gerhard Trubel (eds.): Garden for the soul. Heppenheim Arboretum on Bergstrasse . 1st edition. L&H, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-939629-33-7 , pp. 8-15 .

- Closer to the goal ... 125 years of psychiatry in Heppenheim. From the Grand Ducal State Insane Asylum to the Heppenheim Psychiatric Hospital. 1866-1991 . 1st edition. State Welfare Association Hessen , Kassel 1991, ISBN 3-89203-016-2 .

- Georg Ludwig: Report on the building of the insane asylum and nursing home in Heppenheim . In: General journal for psychiatry and psycho-judicial medicine . tape 19 , 1862, pp. 522-532 .

- Bettina Winter: The Heppenheim sanatorium and nursing home from 1914–1945 - from crisis to catastrophe . In: Psychiatry in Heppenheim. Forays into the history of a Hessian hospital 1866–1992 (= historical series of publications by the State Welfare Association of Hesse. Sources and studies ). 1st edition. tape 2 . Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen , Kassel 1993, ISBN 3-89203-024-3 , p. 63-96 .

Web links

- State Office for Monument Preservation Hessen (Ed.): Psychiatric Hospital In: DenkXweb, online edition of cultural monuments in Hessen

- Chronicle of the clinic on the Vitos Heppenheim website

Individual evidence

- ↑ State Office for Monument Protection Hesse: Ludwigstrasse 54

- ^ Salina Braun: healing with defects. Psychiatric practice in the institutions Hofheim and Siegburg 1820–1878 (= publications of the Max Planck Institute for History . Volume 203 ). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2009, p. 131-133 .

- ↑ Eller: Georg Ludwig. P. 26.

- ↑ Miscelles . In: General journal for psychiatry and psycho-judicial medicine . tape 23 , 1866, pp. 178-179 .

- ^ The meeting in Heppenheim . In: General journal for psychiatry and psycho-judicial medicine . tape 24 , no. 6 , 1867, p. 828 .

- ↑ Eller: Georg Ludwig. passim .

- ↑ Gulden: Garden for the soul. Pp. 10-12.

- ↑ 125 years of psychiatry in Heppenheim. Pp. 18-20.

- ↑ Winter: 1914–1945. Pp. 66-67.

- ↑ Winter: 1914–1945. Pp. 76-91.

- ↑ Winter: 1918–1945. Pp. 91-93.

- ↑ Marion Menrath: Dark chapter of the history of psychiatry. In: Starkenburger Echo . March 5, 2015 ( echo-online.de ).

- ↑ Peter Eller: The state sanatorium and nursing home in the years 1945–1953 . In: Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen (Hrsg.): Psychiatrie in Heppenheim. Forays into the history of a Hessian hospital 1866–1992 (= historical series of publications by the State Welfare Association of Hesse. Sources and studies ). 1st edition. tape 2 . Self-published by the Hessen State Welfare Association, Kassel 1993, ISBN 3-89203-024-3 , p. 97-102 .

- ↑ Klaus-Martin Berger, Helmut Gondolph: Structural priorities of the last decades . In: Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen (Hrsg.): Psychiatrie in Heppenheim. Forays into the history of a Hessian hospital 1866–1992 (= historical series of publications by the State Welfare Association of Hesse. Sources and studies ). 1st edition. tape 2 . Self-published by the Hessen State Welfare Association, Kassel 1993, ISBN 3-89203-024-3 , p. 113 .

- ↑ Gerlinde Scharf: Vitos Clinic arrives at the new location . In: Bergstrasse Anzeiger . September 4, 2014 ( echo-online.de ).

- ↑ Attractive residential location on the former clinic site in Heppenheim. In: Bergstrasse Economic Region. Wirtschaftsförderung Bergstrasse GmbH, May 26, 2014, accessed on March 31, 2015 .

- ^ A b Marion Menrath: Life between park and vineyards . In: Bergstrasse Anzeiger . May 17, 2014 ( morgenweb.de ).

- ↑ Marion Menrath: High quality apartments in an old clinic. In: Bergstrasse Anzeiger . November 7, 2014 ( morgenweb.de ).

- ↑ Marion Menrath: "66 apartments in the north wing". In: Starkenburger Echo . November 27, 2011 ( echo-online.de ).

- ^ Marion Menrath: New life in the bistro "Am Eckweg". In: Starkenburger Echo . September 4, 2014 ( echo-online.de ).

- ^ Marion Menrath: Construction matters, buses and fire brigade . In: Starkenburger Echo . March 12, 2015 ( echo-online.de ).

- ↑ Gulden: Garden for the soul. P. 9.

- ↑ Eller: Building history. Pp. 26-27.

- ↑ Gulden: Garden for the soul. Pp. 11-12.

- ↑ Ludwig: Report. Pp. 522-529.

- ↑ Garden for the soul . In: Erik Roßnagel, Stefanie Egenberger, Gerhard Trubel (eds.): Garden for the soul. Heppenheim Arboretum on Bergstrasse . 1st edition. L&H, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-939629-33-7 .

- ↑ Gulden: Garden for the soul. P. 10.

- ↑ Wolfgang Richter, Jürgen Zänker: The bourgeois dream of the aristocratic castle. Aristocratic designs in the 19th and 20th centuries . 1st edition. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1988, ISBN 3-498-05712-X , p. 117-121 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Richter, Jürgen Zänker: The bourgeois dream of the aristocratic castle. Aristocratic designs in the 19th and 20th centuries . 1st edition. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1988, ISBN 3-498-05712-X , p. 118 .

- ↑ Marion Menrath: "Garden for the soul". In: Starkenburger Echo . March 5, 2015 ( echo-online.de ).