Actual birds of paradise (genus)

| Real birds of paradise | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

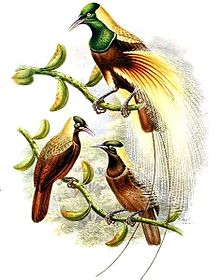

Little bird of paradise ( Paradisaea minor ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Paradisaea | ||||||||||||

| Linnaeus , 1758 |

The actual birds of paradise ( Paradisaea ) are a genus from the family of the birds of paradise (Paradisaeidae) and include seven species . All species live in New Guinea or on islands bordering on New Guinea. All species have in common that the adult males have noticeably elongated, silk-like flank feathers. Actual birds of paradise are long-lived birds that can live up to 33 years of age in captivity. The ornamental feathers and bellows of the actual birds of paradise were and are processed by the indigenous ethnic groups of New Guinea into traditional head and body decorations. Ornamental feathers also played a major role in the western fashion industry of the 19th and early 20th centuries. They were used to decorate women's hats.

Most of the species of birds of paradise are classified as safe by the IUCN . However, among the species that are counted among the actual birds of paradise, there are no fewer than three species whose population status is classified as causing concern. The Blue Bird of Paradise and the Lavender Bird of Paradise , a Inselendemit , where disclosure of the islands of Normanby and Fergusson in southeastern New Guinea is limited, (be as vulnerable vulnerable ) classified. Together with the broad-tailed paradise hop , which belongs to the genus Epimachus , they belong to the species among the birds of paradise that are most threatened. The red bird of paradise , on the other hand, is judged as potentially endangered ( near threatened ).

Actual birds of paradise belong to those species that interbreed with other species within their own genus as well as other species of the family of birds of paradise. Among the species with which hybrids occur include parotia , ptiloris , cicinnurus and the twelve-wired bird-of-paradise .

description

Body type and measurements

Without the greatly elongated middle control spring pair, the males reach a body length between 30 and 43 centimeters. The smallest species is the blue bird of paradise, in which the males can weigh between 158 and 189 grams. The great bird of paradise reaches the greatest body length, but no data are available for the weight of the males. The males are on average around 10 to 15 percent larger than the females. The beak is always straight and up to 20 percent longer than the head. The nostrils are covered with feathers. Apart from the greatly elongated central pair of control feathers, the tail plumage is not tiered, but slightly rounded. The wings are long.

male

All adult males of the seven species that belong to the genus of the actual birds of paradise have long, silk-like flank feathers in common. The middle pair of control springs is also greatly elongated and only has outside and inside flags on the spring base. It then turns into wire-like shafts that protrude far beyond the rest of the tail plumage. They also have comparatively light, often chalky blue-gray looking beaks. With the exception of the emperor's bird of paradise , they either have a yellow crown or a yellow back of the head, and this coloration is partly continued on the coat. The chin and throat are iridescent greenish and in several species set off from the brown chest plumage by a narrow collar.

The emperor's bird of paradise is the species with the most deviating plumage. The head and coat are black, whereas the wings and the underside of the flank feather are blue. The top, on the other hand, is reddish brown. In the other species, the side-like flank feathers are white, yellowish, orange-red to crimson-red.

Young males initially have plumage that is similar to that of females. They only wear the full plumage of the males when they are several years old.

female

The sexual dimorphism is pronounced in all species, the slightest differences between males and females can be found in the blue bird of paradise . Compared to the males, the females are generally much less feathered. They are dominated by brown tones. For example, in the female of the Raggi bird of paradise, the back of the head, the neck and a narrow front neck collar are brown-yellow. The plumage is otherwise brown, with the belly slightly lighter. The females of the actual birds of paradise are on the underside of the body either no or only slightly developed transverse bands. Compared to the plumage of other bird of paradise species, it is a bit more conspicuous overall.

Distribution area and habitat

The actual birds of paradise occur predominantly in New Guinea. The individual species occur in different regions of New Guinea, their range only partially overlaps. New Guinea, the largest island in the world after Greenland, is therefore the main area of distribution of the genus. However, the distribution area of the genus also includes islands off the coast of New Guinea. Birds of paradise are found on the following islands:

- Misool : The 2041 km² island is one of the four main islands of the Raja Ampat archipelago off the coast of western New Guinea . Here the little bird of paradise occurs.

- Waigeo , Gemien, Saonek, Gam and Batanta : The islands are all part of the Raja Ampat archipelago: Waigeo is the largest of the four main islands of the archipelago with an area of 3,155 km². The red bird of paradise is represented on these islands.

- Yapen : The 2,278 km² island is located in Cenderawasih Bay . The little bird of paradise, which otherwise has a focus on New Guinea, also occurs here.

- Aru Islands : The Indonesian archipelago is located about 150 km south of New Guinea in the Arafura Sea . This is where the great bird of paradise occurs, whose main distribution area is otherwise the southwest of New Guinea.

- Fergusson and Normanby : Both islands are part of the D'Entrecasteaux Islands , an archipelago that lies in the Solomon Sea east of New Guinea. They are the exclusive range of the lavender bird of paradise.

Unlike most birds of paradise, the actual birds of paradise are also more common in the lowlands. There are basically forest birds that colonize lowland to low mountain range forests. Only the blue bird of paradise populates exclusively high regions. Female-colored individuals can generally be seen more often at the edge of the forest, while the males tend to be found in the interior of the forest.

food

Actual birds of paradise live on fruits and insects, which they usually find in the tree canopy.

Reproduction

The males of the actual birds of paradise are polygynous , that is, they mate with the largest possible number of females. The partners do not enter into a marriage-like relationship after the pairing, but separate again immediately afterwards.

Courtship

The group courtship of the males takes place at so-called leks . The leks exist for several years, sometimes for decades. In the Varirata National Park, a Lek of the Raggi Bird of Paradise has been used for courtship for more than 20 years. In addition to these long-standing leks, there are also some in this species where males only appear for a short time. They are located near abundant feeding grounds and usually only last for 14 days. Leks are known for the little bird of paradise that have lasted significantly longer than those of the Raggi bird of paradise. Members of indigenous ethnic groups recorded that they had hunted the males in their magnificent plumage for at least three generations at individual courtship sites. This would mean that individual mating sites of this type would exist for at least 60 to 100 years.

The males present themselves on individual branches, while the courtship goes through individual, increasingly intense phases. For individual, better-studied species such as the Great Bird of Paradise and the Raggi Bird of Paradise, the literature distinguishes between courtship phases such as “Convergence Display”, “Static Display” and “Copulation Display”. With the Raggi bird of paradise, for example, courtship begins with the males raising their elongated flank feathers and flapping their wings half open ( convergence display ). In the second part of the courtship ( static display ), the males assume a rigid pose in which only the wings are raised and the head is lowered again and again. The flank feathers are particularly evident and the females can "inspect" the individual candidates. During this courtship phase, the males also make clicks by quickly closing their beak or rub their beaks on branches. The courtship can end here or the copulation phase ( Copulation Display ) follows . With increasing, forwards and backwards jumping movements along the branch, the male approaches the female and makes clicking sounds. It surrounds the female with its wings in order to eventually jump over and copulate.

Nest, clutch and rearing of nestlings

The females build the nest alone, breed alone and raise the young alone. They breed in cup-shaped tree nests. The clutch consists of one or two ocher-colored eggs, which have the elongated spots and hairlines typical of the subfamily of the actual birds of paradise. The incubation period is between 17 and 21 days, the nestling period is between 14 and 27 days.

Life expectancy

Since many species of the actual birds of paradise occur in remote regions, comparatively few individuals have so far been ringed and then found again. In principle, however, it can be assumed that birds of paradise live comparatively old. This is also indicated by the few re-finds of ringed birds and the experiences from captivity:

- The age record for a male Raggi bird of paradise living in the wild is held by a bird ringed on Mount Missim on September 1, 1980. At that time he still wore the female-like plumage typical of subadult males. It was recaptured in July 1997, at which time it was wearing the full adult plumage of a male. He was at least 16 years and 10 months old at the time.

- A hand-reared male Raggi Bird of Paradise lived in the Baiyer River Sanctuary for 25 years. A male kept in Taronga Zoo , Sydney, mated with a female when she was at least 33 years old. Two young birds were successfully raised from the mating.

Systematics

The genus includes seven species, the range of which is largely free of overlap.

- Great Bird of Paradise ( Paradisaea apoda Linnaeus , 1758 ) - Found in the lowlands south of the central mountain range in New Guinea . There the distribution ranges from Timika eastwards to the watershed of the Fly and Strickland Rivers . It is also found on the Aru Islands to the south . Despite this extensive distribution area, no subspecies are distinguished.

- Lavender bird of paradise ( Paradisaea decora Salvin & Godman , 1883 ) - island endite, its occurrence on the islands of Fergusson and Normanby. No subspecies are distinguished.

- Emperor Bird of Paradise ( Paradisaea guilielmi Cabanis , 1888 ) - found on the Huon Peninsula in northeast Papua New Guinea. No subspecies are distinguished.

- Lesser Bird of Paradise ( Paradisaea minor Shaw , 1809 ) - The range extends from Misool Island across Vogelkop and the northern half of central New Guinea to the north coast of the Huon Peninsula as the easternmost range. There are three subspecies.

- Raggi Bird of Paradise ( Paradisaea raggiana P. L. Sclater , 1873 ) - Occurring in the south and northeast of Papua New Guinea. The western limit of distribution is the watershed of Fly and Strickland Rivers and the extreme eastern edge of the Trans-Fly ecoregion . In the north the distribution area extends to the upper reaches of the Ramu . In Madang Province , it is also found in the coastal regions. There are four subspecies for this species.

- Red bird of paradise ( Paradisaea rubra Daudin , 1800 ) - found on the islands of Waigeo, Gemien, Saonek, Gam and Batanta off the west coast of New Guinea. No subspecies are distinguished.

- Blue bird of paradise ( Paradisaea rudolphi ( Finsch & AB Meyer , 1885) ) - The occurrence is limited to the Horseshoe Mountains and the southeast of Papua New Guinea. The distribution area is disjointly distributed over two high mountain landscapes. There are two subspecies.

Big, small and Raggi Birds of Paradise form a super spec . The island endorsements Lavender Bird of Paradise and Red Bird of Paradise are sister forms of the Great Bird of Paradise.

The actual birds of paradise have long been considered closely related to the Reifel birds. Due to their similar lifestyles and behavior, the thread hop and the ribbon bird of paradise are now classified as closely related species.

hybrid

The tendency of birds of paradise to cross with other species in their family was already described by Anton Reichenow at the beginning of the 20th century and thus almost earlier than for any other bird family. Within the genus of the actual birds of paradise, hybrids are only unknown for the lavender-bird of paradise. In its distribution area only the crowded paradise crow and the sonic manucodia from the family of birds of paradise occur and both species are monogamous.

Hybrids within the genus

Hybrids are particularly common between the Raggi Bird of Paradise and the Great Bird of Paradise: the males of this latter species mate with females of the Raggi Bird of Paradise. There are numerous hybrid males on many leks, but this does not mean that only males emerge from such crossings: Most of the hybrids that are discovered are males because they have different plumage characteristics than the more inconspicuously colored females.

Along the upper course of the Ramu is a 35-kilometer-wide corridor in which the distribution area of the Raggi Bird of Paradise and the Little Bird of Paradise overlap. A number of hybrids between the two species have been observed in this area. The range of the two species may also overlap on the west coast of the Huon Peninsula, so that they can also find hybrids there. In this species, too, it is the males that mate with the females of the Raggi bird of paradise. Raggi birds of paradise also cross with the Kaiser bird of paradise. There is also a type specimen which was originally described as Paradisaea bloodi and which is now considered a cross between the Raggi bird of paradise and the blue bird of paradise.

So far, no hybrids between the large and the small bird of paradise have been detected. However, it is very likely that the two species will cross. In contrast, hybrids between the Emperor's Bird of Paradise and the Little Bird of Paradise have been detected in the Finisterre Mountains area on the Huon Peninsula .

Hybrids outside the genus

Crossings of actual birds of paradise with birds of paradise that do not belong to this genus occur less often. Occasionally they are initially described as a distinct species.

The type specimen , which was originally described as Janthothorax bensbachi , is one such example of a hybrid that was initially granted a species status. In the meantime, however, this specimen is considered a cross between the magnificent bird of paradise and the small bird of paradise. However, only one of the bellows found in museums is known as such a hybrid. On the other hand, five bellows are known, which are very likely to have emerged from crossings between the thread hop and the little bird of paradise. They were originally described as Paradiese mirabilis or Janthothorax mirabilis . Another type is considered to be a cross between the little bird of paradise and the sickle-tailed bird of paradise .

Real birds of paradise and humans

Dedication names

- The specific epithet rudolphi of the blue paradise bird ( Paradiesaea rudophi ) honors the Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria-Hungary . At the same time, his wife was honored in a similar way: the German name and the specific epithet of the Stephanie-Paradieselster , a type of paradise star , which also belongs to the birds of paradise , were awarded in honor of Stephanie of Belgium at the time of the first scientific description of the Crown Princess of Austria-Hungary .

- The specific epithet of the Kaiser bird of paradise ( Paradiesaea gulielmi ) is reminiscent of the German Emperor Wilhelm II. Gulielmili is the medieval Latin form of Wilhelm.

Imprisonment

Species of the true birds of paradise have long been kept in captivity. The British naturalist Thomas Pennant (1726–1798) mentioned that a living Great Bird of Paradise had been sent to Great Britain before 1790. René Primevère Lesson (1794–1849) reports that in 1828 he saw two great birds of paradise on the Indonesian island of Ambon that a Chinese merchant kept.

Alfred Wallace sent a pair of Little Birds of Paradise to Great Britain in the 1860s, the pair were kept at London Zoo from April 1860. A fully grown male of the blue bird of paradise was sent to British politician William Ingram in 1907 and was kept a breeding pair by the New York Zoological Society in the 102s.

The number of successes in breeding with actual birds of paradise has increased in recent years. Successful breeders now include the San Diego Zoo, the Bronx Zoo in New York, the German World Bird Park in Walsrode and Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation in Qatar . Successful offspring of the blue paradise bird, on the other hand, have been particularly successful in aviaries in New Guinea. For the breeding of the polygamous species, in which the males gather at a common playing field, there is an aviary row so that females can only be left with a male for a short time and then separated again. If the male stayed with the female, there would be a risk that it would not only disturb the brood, but also destroy the nest and eggs or eat the nestlings.

From captivity, new knowledge about the reproductive behavior of this species is regularly gained. In an offspring of the little bird of paradise, the mating took place between a female and a male who still wore his youthful dress, which was similar to the female plumage. A number of other observations on the breeding time and rearing of the nestlings were also collected that have not yet been observed in birds found in the wild.

Raggi birds of paradise have also been kept and successfully bred for a long time. Such husbandry successes have been achieved in Papua New Guinea, India, the Taronga Zoo in Sydney, in aviaries in Hong Kong and in the San Diego Zoo , among others . In the Baiyer River Sanctuary, the offspring succeeded in 1979, 1980, 1091 and 1983 with the same breeding pair. The red bird of paradise, on the other hand, is more common in Asia in captivity. For example, a zoological garden in Singapore looks after it. However, until the end of the 20th century, it was mainly zoological gardens in the USA that were successful in breeding with this species. Emperor Birds of Paradise were successfully bred in Sydney and in the Baiyer River Sanctuary , Papua New Guinea, among others .

Bellows and feathers as a prestige object of indigenous ethnic groups of New Guinea

Huli headdress with feathers from magnificent and raggi birds of paradise as well as tail feathers from paradise stars

The feathers of a number of birds of paradise are made into traditional head and body decorations by the indigenous ethnic groups of New Guinea. With a few exceptions, this jewelry is worn exclusively by men. When processing such jewelry, the feathers and hides of the males of the actual birds of paradise with their silky, elongated, white to reddish flank feathers are also used. With their comparatively large role played by the actual birds of paradise, it also plays a role that they predominantly occur in lowland and low mountain range forests, which are comparatively more densely populated than the high mountain forests in which most of the other birds of paradise live.

The hunt is concentrated exclusively on the males because the females lack these decorative feathers. Before rifles were widespread in New Guinea, hunting was carried out exclusively with bows and arrows, limesticks and traps. Hunters often used the traditional leks - the courtship grounds where several males gathered - to hunt the males with their ornamental plumage. When hunting, blunt arrows were preferred so as not to damage the plumage. Traditional hunting does not necessarily have to reduce the population: Despite the generation of hunting for the Little Bird of Paradise, the population is stable and in some regions the species is even very common - the Little Bird of Paradise is one of the most common birds on the island of Yapen the lowlands, in the foothills as well as in mountain forests. The situation is different with the Great Bird of Paradise: In the 1970s it was found that the population of Great Birds of Paradise in the regions into which rifles had been introduced fell significantly. Where this was not yet the case, the numbers remained comparatively high. The individuals of this species were also noticeably tamer there.

Bellows and feathers in western hat fashion

In Europe and North America, between the last quarter of the 19th century and around 1920, women's hats were preferably decorated with bird feathers, but also with bird fur . Wings, heads and complete bird hides were used. The skins of birds of paradise and especially those of the actual birds of paradise with their conspicuous, elongated flank feathers were particularly popular, as is shown by numerous photos showing the hunters with the skins of the birds they shot. In Kaiser-Wilhelms-Land , the north-eastern part of New Guinea, which was part of the German colonial empire until 1919 , high license fees had to be paid for the right to hunt because of the high prices that could be achieved with the bird of paradise hide. The wholesale price for such a bellows was about 130 marks on the German market before the First World War. That was half the monthly salary of a police officer. It is estimated that the respective auctions in London, New York and Paris between 1905 and 1920 sold between 30,000 and 80,000 Birds of Paradise every year. As early as 1912, the United States had issued a ban on the import of feathers and feathers from wild birds. In the German empire, the "Bund für Vogelschutz" (forerunner of today's NABU ) campaigned against the fierce resistance of the fashion industry against the "bird murder for fashion purposes". In 1913 the Reichstag dealt with the issue of the protection of birds of paradise and in 1914 the hunt for all bird of paradise species was banned in the colony.

Use of feathers in other crops

The flank feathers of the Great Bird of Paradise have adorned the headgear of high-ranking members of the Nepalese royal court for centuries. They were worn by the king, the prime minister and generals on special ceremonial occasions. Before the export ban, the feathers came from New Guinea to Nepal via traditional trade routes. The Nepalese crown uses particularly long flank feathers, which emerge from a jeweled setting like a horse's tail.

At the coronation of the Nepalese King Mahendra in 1957, the feathers still in the possession of the Nepalese royal family were largely damaged. Due to the export ban that has now been passed, feathers can no longer be legally acquired on the trade route. At the suggestion of the ornithologist Ernest Thomas Gilliard , representatives of the US Embassy sent feathers to the Nepalese royal family, which had long been in the American Museum of Natural History since customs confiscation .

As modern symbols

Stylized birds of paradise are now the symbol of numerous Papua New New Zealand and Indonesian organizations and companies. Because of their conspicuous plumage, stylized representations of actual birds of paradise are often used.

- The Indonesian 20,000 rupee banknote issued between 1976 and 2000 depicts a male red bird of paradise.

- The flag of Papua New Guinea has been adorned with a stylized Raggi bird of paradise since 1971.

- The national emblem of Papua New Guinea also shows a stylized Raggi bird of paradise

- The Air Niugini corporate symbol is also a stylized actual bird of paradise. The painting of individual aircraft shows.

- Several of Papua New Guinea's export products show actual birds of paradise on their packaging. As a particularly striking example, Frith and Beehler cited coffee packaging, which shows the blue bird of paradise and the ragge bird of paradise, both of which are found in the coffee growing area.

literature

- Michael Apel, Katrin Glas, Gilla Simon (eds.): Natural and cultural history of the birds of paradise. Munich 2011, ISBN | 978-3-00-0352219-5.

- Bruce M. Beehler, Thane K. Pratt: Birds of New Guinea; Distribution, Taxonomy, and Systematics. Princeton University Press, Princeton 2016, ISBN 978-0-691-16424-3 .

- Mark Cocker, David Tipling: Birds and People . Jonathan Cape, London 2013, ISBN 978-0-2240-8174-0 .

- Clifford B. Frith, Bruce M. Beehler : The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1998, ISBN 0-19-854853-2 .

- W. Grummt , H. Strehlow (Ed.): Zoo animal keeping birds. Verlag Harri Deutsch, Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-8171-1636-2 .

- Eugene M McCarthy: Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, ISBN 0-19-518323-1 .

- Thane K. Pratt, Bruce M. Beehler: Birds of New Guinea. Princeton University Press, Princeton 2015, ISBN 978-0-691-09562-2 .

Web links

- Voice of the Little Bird of Paradise on Xeno-Canto

- Voice of the Ragge Bird of Paradise on Xeno-Canto

- Exhibition on birds of paradise in the Bamberg Natural History Museum

- English-language article on hat fashion with birds of paradise: The Bird hat - Murderous millinery

Single receipts

- ↑ Handbook of the Birds of the World on the Lavender Bird of Paradise , accessed August 20, 2017

- ↑ a b Handbook of the Birds of the World on the Blue Bird of Paradise , accessed on August 20, 2017

- ↑ Handbook of the Birds of the World on the Red Bird of Paradise , accessed August 20, 2017.

- ↑ a b c d e Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 438.

- ↑ a b Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 488.

- ↑ a b Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 448.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 449.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 439.

- ↑ Grummt & Strehlow (Ed.): Zoo animal keeping birds. P. 750.

- ↑ a b Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 463.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 444.

- ↑ a b c Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 469.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 468.

- ^ A b McCarthy: Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World. P. 228.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 471.

- ^ McCarthy: Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World . P. 230.

- ↑ a b c McCarthy: Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World. P. 231.

- ^ McCarthy: Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World. P. 229.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 483.

- ↑ a b Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 456.

- ↑ a b Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 498.

- ↑ a b Grummt & Strehlow (ed.): Zoo animal keeping birds. P. 753.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 482.

- ↑ Apel et al .: Natural and cultural history of the birds of paradise. P. 57.

- ↑ Apel et al .: Natural and cultural history of the birds of paradise. P. 58.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 447.

- ↑ a b Apel et al .: Natural and cultural history of the birds of paradise. P. 75.

- ↑ The Bird hat - Murderous millinery , accessed August 22, 2017.

- ↑ Apel, Michael: Natural and cultural history of the birds of paradise . Ed .: Museum Mensch und Natur. Munich 2011, p. 83 .

- ^ Negotiations of the German Reichstag. Retrieved January 22, 2020 .

- ↑ Apel et al .: Natural and cultural history of the birds of paradise. P. 90.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 146.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 147.