Färmeltal

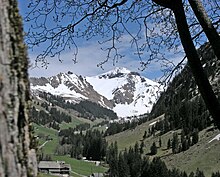

The Färmeltal , called “Färmel” by the locals, is a closed side valley of the Obersimmental in the Bernese Oberland in Switzerland. The valley is drained by the Färmelbach, which flows into the Simme in Matten . The history of the valley can be traced back over 700 years. The life of mountain farmers is “shaped by life with natural hazards”.

Location and geography

To get to the Färmeltal, take the train from Bern via Spiez to Zweisimmen , where the traveler gets on the Montreux-Berner Oberland Railway in the direction of Lenk . In Matten, which belongs to the municipality of St. Stephan , the road and hiking trails branch off into the Färmeltal. There is no public transport in the valley itself, but it can be reached by car or on foot.

The Färmeltal belongs to the pre-Alps . The highest point on the valley floor, where the road ends, is 1651 m. ü. The most famous mountain in the Färmeltal is the Albristhorn with a summit height of 2762 m. ü. Other peaks are the Gsür with 2708 m above sea level. M. and the Spillgerten with 2476 m. ü. On the western side you can get from St. Stephan on the old mule track over the attic into the Färmel and further over the Pass Grimmifurggi 2022 m. ü. M. into Diemtigtal .

The valley is sickle-shaped and about 9 km long. The valley floor runs northeast at the beginning and ends in a southeast direction at the foot of the Färmelberg. The character of the valley corresponds to a trough valley , geologically it belongs to the Penninic . In addition to limestone mountains like the Spillgerten , the valley consists of different types of flysch . It is the geological structure that has given rise to "the varied design" of the area.

With its large differences in altitude, the valley covers both subalpine and alpine vegetation levels. The tree line is around 1800 m. ü. The forest primarily functions as a protective forest against avalanches , landslides and rockfalls . Conifers such as spruce and fir make up the largest proportion, while the sycamore maple makes up a small percentage .

The following can be read about the Färmeltal in a landscape analysis by the canton of Bern:

“The cultural landscape consists of a large proportion of relatively steep forest and a diverse mosaic of forest, woods (accompanying the stream), meadows, pastures and scattered settlements in the flatter areas. Cattle are summered in the higher areas. Seasonally used facilities and useful buildings (stables, fences, wells), which reveal the traditional relationships between buildings, landscape and use, are characteristic.

The arid sites and wetlands, which are widespread throughout the area, are of particular ecological value. Below the summit of the Albristhore lies the Albrist moorland of particular beauty and of national importance. "

The moor landscape on the Albrist is included in the federal inventory of moor landscapes with property number 339 and covers 333 hectares. The protected landscape is not used as pasture , but as mountain meadow. Certain plots are only cut every two years, other particularly wet areas even less often. The dry hills between the moors are mowed more frequently, so that "there is a mosaic-like pattern of different plant communities and stages of use."

etymology

The term Fermel , which is based on High German, can still be found today , for example on signposts in the Simmental or on older maps. In keeping with today's zeitgeist, which gives more weight to regional peculiarities, the name Färmel is increasingly being used. On today's maps, the river and the valley name are consistently marked with Färmel. Färmeltal registered.

Historically, the names "Vermil" and "Fermill" have been handed down. There are various interpretations of their origin. The Latin word "ferrum" for iron would refer to the red stone with iron content that can be found in the sleeve. Place names with similar sounding names in Austria and the rest of Switzerland, all of which were settled by Walsers , point in a different direction . The origin of the name has not yet been clearly clarified.

The historical and current field names of the valley are of particular interest . They refer to the proper names of owners and scenic features that have been passed on over generations. "Bibertsche" indicates a stream flowing through it, "Brand" indicates clearing in the forest, "Bruch" indicates marshland, "Blütti" indicates bare, bare ground. "Stalde", a common field name, stands for a steep path that is still ahead of you, or "Stigelsgueot", which indicates an incline. Names such as "Sparisboden", "Tannersbode" or "Gassebrunner" refer to owners who lived a long time ago, or they point to the current manager, as in the case of Gobelis or Zahlers Weid.

history

The Simmental has been settled since prehistoric times, but “a denser settlement” that reached as far as St. Stephan “probably only started in the Alemannic period”. The oldest mention of the Färmeltal comes from a document from the Sels monastery from 1275. Other documents from 1329 and 1352 deal with sales of hay meadows in Vermil . In addition, the history of the Färmels is more or less in the dark until the 16th century.

In 1391, the Bernese bought the lordship of Simmenegg , today's Obersimmental , from Baron Rudolf von Aarburg , in order to incorporate it into the already conquered areas in the Simme valley. With the change of rule, the farmers were given administrative functions in addition to their original economic functions. This is reflected in the recent land registers that are bäuertweise added. “At the latest in the 16th century, new user corporations, the mountain cooperatives, emerged.” They are the result of the livestock use that has become established throughout the Simmental. The traditions of the farmers and alpine corporations from the Färmeltal confirm their appearance from this period.

In 1947 Paul Köchli wrote in his study of the upper limit of the permanent settlements in the Simmental:

“The temporarily inhabited settlements are in the pasture areas and are visited in summer. The pasture areas represent an extension of the usable soil and thus often enable the emergence of numerous permanent settlements in the Alpine valleys. "

This development from initially seasonal stays to permanent settlements has also taken place in the Färmeltal. A new farmer is mentioned in the register of the castellan Rudolf Ougspurger from April 7, 1677:

"It consists of a number of houses, so that they are almost only inhabited in summer, but it is not a village."

Today there are 14 farms in Färmel and the population is around 76, including 16 children.

economy

The numerically small population of the Färmeltal lives from the livestock industry. Forest management and tourism serve as a sideline. As early as 1911, the valley's ranchers formed a cattle breeding cooperative. With one exception, the alpine pastures are operated on a cooperative basis.

In 2017 there were 14 farms on the actual valley floor, which together form the Bäuert Färmel.

The neighboring regions are also organized as a cooperative. The Bäuert Obersteg – Zuhäligen lies in the east of the valley on the height. The Färmelberg at the end of the valley is managed by an alpine corporation.

In the Albrist area above the valley, there is a single alpine farm on the Ober-Albrist and three alpine farms operate the Lower Albrist together.

Farms

The Bäuert im Färmeltal is a citizen's corporation and contains the remains of the Alemannic market cooperative. It owns the forests around the village and often also the pastures. The highest body is the farmers' assembly, di Püürtsgmìì . Members have a right to firewood and construction wood. The duties include the maintenance of the paths, bridges and Pürttagwärch . In the melodic Simmental dialect, a description of the Bäuert sounds as follows:

“The Püürstatti are on the residential buildings ù means at least the same as the Füürstatrier. The owner uses who he lives in his league ù Stüreni pays for revenge. It is not possible to heat up the country. Di Püürtsgmìì cha saw, whether you want it for the new Wohnhus uufnee or net. Mis Huus püürt, what is Püürsträcht druffe. I ha ûûss Huus ûûser Tächter, si cha ds Pürrier net enjoy, will si nù not live here. Earlier hii di Pürti d Schuelhüser bbuwe ùnder receives ùn o ds firewood gliferet. Large weighing routes including Brüggene ù mixed o with Schweli hii di Püürti ù for the area ù the maintenance is made. Di mixed Uufgabi hìì due fûûr ù fûûr di Gmììndi ùbernoe. "

Grows sleeves

The Färmel is one of seven farmers who are united in today's St. Stephan parish. The alpine cooperative has been handed down since 1615. The land register shows that the valley used to be mainly inhabited in summer and that the settlement consisted of a few houses.

The Seybuch der Bäuert , which corresponds to today's land register and in which the rights to the general property of forest and pasture are specified, was completely destroyed in a lightning strike in the house of Hans Rieder im Zil on August 21, 1754, which amounted to a medium catastrophe. Since 1754 the rights of the landowners and the statutes of the farmers have been listed in the new Seybuch until they were later incorporated into the land register .

In the Seybuch, the rights to the common property were defined with the unit of measure at that time Jucharten (36 ares ). In the past, a distinction was made as to whether the land was fertilized or unfertilized (Riedmaad). The more land a farmer owned in the valley, the greater his share of the common property in the Allmi and Bibertschen pastures . This one-time rule still exists to this day. The areas of the homes in the valley are proportionally converted to grazing rights. The distribution of rights can only be changed by buying or selling land in the valley.

The use of the firewood is also regulated by the Bäuert. All landowners in the Färmel who have a fireplace and actually live in the valley have a right to firewood (Feuerstattrecht). Every property in the farmer's area has the right to purchase 1 m³ of construction timber for every 3 Jucharten land area every 2 years. The duties included responsibilities such as randen (farmer's tax), the maintenance of the paths or the clearing of spills, if necessary.

In the Bäuert's logs, for example, you can read:

"3. 2. 1952 The Matten farming community asks whether they can go to the Witi to graze their goats again in the summer. The request is not granted because there is currently no milk shortage and there are no poor people in Matten as before. "

or elsewhere:

"26th 9. 1956 Sale of the farmers springs in Bibertschen to d. Grodey Well Cooperative. It is unanimously decided to sell water to the said cooperative; in the second vote, it is specialized that the sale should be limited to the Kindbettere and Blachtibrunnen with the express reservation that the farming community should always have the necessary spring water, spec. in the event that natural disasters such as earthquakes should dry up the springs on the sunny side. "

Another excerpt from May 5, 1964 deals with the request to the St. Stephan municipal council for the establishment of a road cooperative, as required by law.

The Bäuert Färmel is still an important authority in the Färmeltal and has a guaranteed seat on the St. Stephan municipal council.

Alpine corporation Färmelberg

The alp is located at the end of the Färmeltal at an altitude between 1500 and 2200 m. ü. M. and is supported by 45 members of the cooperative. It comprises 340 hectares of pasture land , 20 hectares of woodland pasture , 40 hectares of wild hay and is one of the larger Alps in the municipality of St. Stephan. There are 22 buildings in the area, 11 of which are used for alpine farming and are privately owned. The alpine cooperative has a water supply and its own springs. The oldest reference to the alpine corporation dates from 1346.

In the Bernese Oberland , the size of an alp in agricultural policy is not determined by the area, but the expected yield is used. The yield is the number of animals that can be grazed in the area in a period of time, called the shock . The alp corporation Färmelberg reports the following earnings figures:

| place | Number of shocks | Period |

|---|---|---|

| Front Bärg | 200 | 28 days (mid-June to mid-July) |

| Hindere Bärg | 200 | 49 days (mid-July to early September) |

| Front Bärg | 200 | 14 days (beginning of September to mid-September) |

| Total | 600 | 91 days |

A normal shock is the designation of the number of shocks with the number 100 times the number of days. The Färmelberg has 182 normal bumps. In comparison, the Bluttlig has 49, the Ober-Albrist 70, and the Unter-Albrist 97 normal shocks.

The farmer himself reckons with the name Rindersweid (RW). The Alp Färmelberg is rated 207 ½ RW, the traditional expression for it is seyet . The Alpine rights are not linked to ownership in the valley and can be traded or leased under the current owners.

Privatalp Bloody

The largely treeless alp with 80 hectares of pasture land, 4 hectares of forest pasture and 6 hectares of wild hay belongs to a single family in the Färmel and thus has an unusually large area for a private valley. It is between 1700 and 2320 m. ü. The spring water supply is ensured by the Grimmialp in Diemtigtal . The energy supply takes place via gasoline engines and solar panels.

The owners of the alp, which they manage in summer, have been documented since the middle of the 19th century. There is a diary of the owner from the years 1948–1957, who wrote down the events on the Alp every day and left a testimony to everyday mountain life from that time.

“Saturday, August 14, 1948. It was a very bad day for us mountain people. Snow down to the valley. We wake up late so that the animals can rest longer. "

“Sunday, August 15, 1948. […] I am ashamed of the lovely cows when we milked them and couldn't give them anything to eat. We had 36 liters of milk from 22 cows, just for the young cattle. I made soup for the pigs. Everything is bewitched: We hardly have any more hay, and that is still very bad, milk was scarce and will now be even scarcer, the number of bulls as never for a long time, weather so bad that we can't even make hay. "

“Monday, September 6, 1948. At the beginning of summer I was worried, we are in great need and now that we want to leave, it is still so nice. We brought 116 head of cattle up here and thank God we were able to return all of them healthy. "

Bäuert Obersteg-Zuhäligen

The Bäuert consists of the parts Obersteg, Lauene, Zuhäligen and Eggen with Fermelboden and Töneloch. The Bäuert has been handed down from the Seybuch registers since 1705. Legend has it that the namesake of the community of St. Stephan lived in this area as a hermit.

In 1992, the Bäuert lost its guaranteed seat in the St. Stephan municipal council because the number of year-round residents has decreased. There are only three farms left and the number of residents has dropped to 24. The number of fireplace owners was 21 in 2017.

The inventor and inventor Johann Wilhelm Freidig (1861–1941) came from Zuhäligen. He cast the perfect five-pound fiber, later manufactured barometers and founded the pewter dynasty Freidig an der Matten.

Alpine corporation Unterer-Albrist

The cooperative has 26 members and is located at an altitude between 1700 and 2300 m. ü. The alp has 158 hectares of pasture land, 4 hectares of woodland pasture, 17 hectares of wild hay and 6 hectares of litter (parched vegetation of wetlands as storage for cattle). In the so-called lower table, that is, on the front Albrist, there are a group of houses in the “Wallis style” by the brook, which give clues to a possible Walser settlement in the past.

Alpine corporation Oberer-Albrist

With 17 members, the cooperative is one of the small associations. Like all other Alpine cooperatives, it is headed by a mountain bailiff, who is now called the president. During his term of office he is the overseer of the alp and organizes the joint work to be done. The term of office of the mountain bailiff is 4 to 6 years, depending on the Alpine cooperative. He represents the cooperative externally and performs his function all year round. The current (2019) Bergvogt of the Upper Albrist is a woman, probably the first in this position.

The alp lies at an altitude between 1660 and 2130 m. ü. M. and has 82 ha of pasture land and 1 ha of litter land. The alp is irrigated via controllable moats.

Wild hay on the Albrist

The Albristmäder are the large wild hay area in the wide hollow between the alpine meadows. The diverse flora is endangered by modern management.

A special feature is the Valais-style irrigation still practiced on a maad on the Albrist

animals and plants

Extensive agriculture, adapted to the environment, has produced a diverse flora and fauna. Of the reptiles , the aspic viper and the adder have been identified. The bird life is with the ptarmigan , black grouse and rock partridge represented in the höhereren documents. Among the smaller birds, the Alpine Brownelle and the Snow Sparrow should be mentioned. The black woodpecker and the three- toed woodpecker drum in the forest and the tawny owl calls every now and then . Alpine choughs and, on rare occasions, golden eagles can be spotted on the terrace of the attic .

In the area of Bluttligs keep chamois and to the chagrin of the local hunters also frequent lynx the area.

The flora of the Alps is famous for its colorful springs. The Färmeltal is no exception. Gentians , rust-leaved alpine rose , silver thistle , Turkish league and the yellow lady's slipper are at home in the valley. Romeye , mother and noble grass , which are valuable for grazing animals , can also be found in the herb-rich pastures.

Natural hazards

The Färmeltal is an exception in the Swiss Alps because the valley is inhabited all year round and is in a danger zone. The residents have to face avalanches, rockfalls and water masses.

Avalanches

The importance of the forest as protection against avalanches has been handed down since the 14th century, but it has only recently become established. Until the end of the 19th century the mountain forest was in a sad state. It was used as pasture for goats and sheep and cleared. As recently as 1924, the Simmental forest population made up 22.5%, "which suggests an intensive pasture expansion at the expense of forestry." The authorities tried late to bring the overexploitation of the forest under control and the local owners and the farmers did each other difficult with the new forest laws. Since 1847, the municipalities have been obliged to draw up a forest management plan and forest use regulations. The implementation turned out to be difficult and dragged on. In the letter from the forest director to the government in Obersimmental from 1887 you can read:

“The farmers 'Fermel' in the parish of St. Stephan, Obersimmenthal; we received the inquiry whether she was obliged to draw up an economic plan for her forests. She believes this is not the case because her forests are 'not corporate but private property of the respective property owners in Fermel.' "

and then continues:

"If the restraint continues, we would have to reduce the previous uses to a level that absolutely secures the existence of the protective forest until the economic plan proves a higher usage authorization."

In the following winter of 1887/1888, 675 avalanches were registered for the whole of Switzerland. One of them, the Witilawine, fell on the Albristhubel on April 25, 1888 and “destroyed five hectares of forest and left behind an extensive avalanche cone 500–600 meters wide, 700–800 meters long and 8 meters high. The Fermelbach was temporarily dammed. "

The then chief forester Christian wrote about this event:

“In this century it (The Witilawine) occurred with the same force [as] in the years 1809, 1839, 1856, so once every 30 years. There have been avalanches every year since 1856, but only locally, while the last avalanche on April 25, 1888 cleared the following areas: Width 21 ha, Hänggisgraben 4 ha, Steinleren 16 ha, total 41 ha. "

He recommends avalanche barriers and afforestation on the Albristhubel.

Since 1944, the WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research SLF has registered 29 avalanches for the Färmeltal, in which three people died and six were injured. Ten avalanches alone fell down into the valley around the Albristhubel. Avalanches are so natural in this area that the locals have given them their own names: "Ahorni-", "Wang" or "Wyti" avalanches. 12 avalanches have been registered in the Albristhorn, Luegle and Gsür area. In winter, the area with its farsightedness is popular with ski tourers and harbors dangers.

The falls on the Bluttlig or the Heuw-Eggli are rare and unpredictable. Electricity, telephone and road connections are affected. It is the forest that absorbs a large part of the destructive force of these avalanches and has saved the houses and their residents from the worst.

Falling rocks

Falling stones, to which people fell victim, have been handed down since the 18th century. It is reported from the year 1723 that the 16-year-old Peter Bringold was buried in St. Stephan on July 26, 1723. "Had tended the sheep in the Fermel-Fliesen, but was found dead on July 24th, and miserable and terribly beaten up, one thinks he was hit by a rolling stone and overthrown, was a boy of good hope." Others Events are reported from the years 1743 and 1806. The last report comes from 1946. A large stone came loose near the Roten Fluh, fell into the valley and damaged a house.

water

When there is heavy rainfall, the brooks can burst their banks explosively, dragging wood and debris with them and becoming a danger.

“After the heavy hailstorm on July 25, 2015, huge masses of debris loosened from the flank of the Albristhorn and roared down through the Birregraben, dug a deep channel in the debris cone and transferred large parts of the Fermelberg with a meter-high layer of rubble. Huge stones swam in the rubble up to the mountain wall. The road was inaccessible from the Muri and the Grod. Three people were brought to safety by helicopter. Stones and rubble covered the bank area right down to the pit. The village of Matten was spared damage thanks to the new Griensammler. "

Reactions

The Färmeltal has a long history of natural hazards and the residents have adopted a behavior to deal with them. For example, the correlation between the two can be clearly seen on maps with buildings and protective forests. The eastern part of the valley, which is prone to avalanches, is not built up and is covered with protective forest up to the tree line. On the western side of the valley, the houses are arranged under the protective forest. In the 2006–2020 forest plan for the region it is stated that “the high proportion of coniferous wood is due on the one hand to the site conditions and on the other hand to the management. Efforts today are to increase the proportion of hardwood in order to increase the stability of the stands and their resistance to bark beetle attacks. "

Many houses are equipped with protective walls against the slope, individual buildings with only one roof shield are built so deep into the slope that avalanches can rush over them. There are solid cellars in renovated residential buildings and in the former school building a civil defense room provides security for the entire population in the event of greatest danger.

The community of St. Stephan and Bäuert Färmel implemented a comprehensive concept for the protection of the population in the winter of 2015/2016, in which it is specified how those responsible should act in the event of an avalanche.

Voices have already been heard calling for the valley community to be dissolved. The free newspaper can read for 20 minutes : “The Färmeltal in the Oberland is in the highest avalanche danger area. The residents fear for their existence not because of the force of nature, but because of the building laws. ”Building laws could prevent buildings destroyed by natural disasters from being rebuilt or houses being expanded. A community representative speaks of a "Lex Färmel", which should find an exception for the valley. When asked about the dangers, the mountain residents take it calmly: "People simply have to live with certain dangers - whether in the mountains or in the city."

literature

- Office for Agriculture and Nature: Landscape Quality in the Canton of Bern. Project perimeter: Obersimmental – Saanenland. October 2014, rev. July 1, 2015 (PDF) Retrieved February 28, 2019 .

- Office for Forests, Natural Hazards, Ueli Ryter: Bernese Oberland avalanche cadastre 1336–2008. Interlaken 2009. (PDF) Retrieved on February 26, 2019 .

- Office for Forests of the Canton of Bern: Regional Forest Plan 22 2006–2020. Obersimmental – Saanen, Spiez February 2006. (PDF) Retrieved on February 26, 2019 .

- Swiss Federal Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research SLF : Snow and Avalanches in the Swiss Alps Winter 1998/1999. Davos 2007. Accessed February 26, 2019 .

- Paul Köchli, Geographica Helvetica 1947: The upper limit of permanent settlements in the Simmental in their dependence on soil structure and agriculture. (PDF) Retrieved March 1, 2019 .

- Manfred Lempen, Elisabeth Bergmann, Peter Bratschi: In the Färmeltal. Zweisimmen 2017. ISBN 978-3-9522412-8-8 .

- Ida Müller: The development of the ownership structure in the Obersimmental, with special consideration of the common land . Diss. Jur. Fac. Bern, 1935. Bern 1937.

- Government Council of the Canton of Bern: Cantonal Sectoral Plan for Moorland Landscapes. Bern 2000. (PDF) Retrieved on March 4, 2019 .

- Collection of Swiss legal sources . Section II, The Legal Sources of the Canton of Bern. Part Two, Agricultural Rights. First volume, The Statute Law of the Simmental (until 1798). First half volume: The Obersimmental. Edited by Ludwig Samuel von Tscharner. Aarau 1912.

- Swiss breeding bird atlas . Distribution of breeding birds in Switzerland and the Principality of Liechtenstein from 1993 to 1996. Sempach 1998. ISBN 3-9521064-5-3 .

- Swiss Seismological Service : COGEAR. MODULES 1a: Historical Earthquakes in the Valais Del. No .: 1a.2.1. January 10, 2010 (PDF) Retrieved March 5, 2019 .

- Ludwig Samuel von Tscharner .: Legal history of the Obersimmental until 1798 . Bern 1908.

- Robert Tuor: Boltigen: a contribution to the historical settlement geography in the Simmental . Berner Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Heimatkunde Volume (year): 37 (1975).

- Isabelle Vieli: "When the high alpine daughter, wrapped in her white robes, thunders down into the valley" . The avalanche winter of 1887/1888 in the Bernese Oberland. Bern Studies in History, Series 1: Climate and Natural Hazards in History, Volume 1. University of Bern 2017. ISBN 978-3-906813-47-9 .

Individual notes

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, foreword.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 14.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, pp. 10-14.

- ^ Landscape quality in the canton of Bern. Project perimeter: Obersimmental – Saanenland. Office for Agriculture and Nature, October 2014, rev. July 1, 2015, p. 5.

- ↑ The upper limit of the permanent settlements in the Simmental in their dependence on soil structure and agriculture . Paul Köchli, Geographica Helvetica 1947, p. 9.

- ^ Landscape quality in the canton of Bern . Project perimeter: Obersimmental – Saanenland. Office for Agriculture and Nature, October 2014, rev. July 1, 2015, p. 16.

- ↑ Cantonal sectoral plan moorland . Government Council of the Canton of Bern, Bern 2000. p. 57.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 148.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, pp. 19–21.

- ↑ The upper limit of the permanent settlements in the Simmental in their dependence on soil structure and agriculture . Paul Köchli, Geographica Helvetica 1947. p. 20.

- ↑ The upper limit of the permanent settlements in the Simmental in their dependence on soil structure and agriculture . Paul Köchli, Geographica Helvetica 1947. p. 20.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal . M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 36.

- ^ Boltigen: a contribution to the historical settlement geography in the Simmental . Robert Tuor, Berner Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Heimatkunde Volume (year): 37 (1975), p. 95.

- ^ Boltigen: a contribution to the historical settlement geography in the Simmental . Robert Tuor, Berner Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Heimatkunde Volume (year): 37 (1975), pp. 106-107.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal . M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 37.

- ↑ The upper limit of the permanent settlements in the Simmental in their dependence on soil structure and agriculture . Paul Köchli, Geographica Helvetica 1947. p. 3.

- ↑ The upper limit of the permanent settlements in the Simmental in their dependence on soil structure and agriculture . Paul Köchli, Geographica Helvetica 1947. p. 20.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal . M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 90.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 152.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 115.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 90.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 73.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 444.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 450.

- ↑ Swiss idiot. Retrieved May 28, 2019 .

- ↑ Usem Simetal Vocabulary . Peter Bratschi, Simmental Zeitung, Zweisimmen, issue April 29 - May 5, 2019.

- ↑ St. Stephan community organization. Retrieved February 23, 2019 .

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 74.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 77.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 78.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, pp. 82–84.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 82.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 93.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 85.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 85.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 86.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 123.

- ↑ Alp portrait Fermelberg in the marketing inventory of Swiss alpine companies. Retrieved February 26, 2019 . ; In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, pp. 228 and 248.

- ↑ Alp portrait Fermelberg in the marketing inventory of Swiss alpine companies. Retrieved February 26, 2019 .

- ↑ Alp portrait bloody in the marketing inventory of Swiss alpine companies. Retrieved February 26, 2019 .

- ↑ Alp portrait Ober-Albrist in the marketing inventory of Swiss alpine farms. Retrieved February 26, 2019 .

- ↑ Alp portrait Unter-Albrist in the marketing inventory of Swiss alpine farms. Retrieved February 26, 2019 .

- ↑ Alp portrait bloody in the marketing inventory of Swiss alpine companies. Retrieved February 26, 2019 .

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 220.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal . M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, pp. 401–402.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal . M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 416.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal . M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, pp. 486–489.

- ↑ Alp portrait Unter-Albrist in the marketing inventory of Swiss alpine farms. Retrieved February 26, 2019 . ; In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 440.

- ^ Anne-Marie Dubler : Alprechte. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . June 25, 2015 , accessed February 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Alp portrait Ober-Albrist in the marketing inventory of Swiss alpine farms. Retrieved February 26, 2019 .

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 443.

- ^ Coordination office for amphibian and reptile protection in Switzerland (karch). Retrieved March 2, 2019 .

- ↑ Swiss Breeding Birds Atlas . Distribution of breeding birds in Switzerland and the Principality of Liechtenstein from 1993 to 1996. Sempach 1998.

- ↑ Information from a local hunter in the attic, Färmeltal Winter 2018.

- ↑ Predator Ecology and Wildlife Management - KORA. Retrieved March 2, 2019 .

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, pp. 497-499.

- ↑ Alp portrait Fermelberg in the marketing inventory of Swiss alpine companies. Retrieved February 26, 2019 .

- ↑ "When the high alpine daughter thunders down into the valley wrapped in her white robes" . The avalanche winter of 1887/1888 in the Bernese Oberland. Isabelle Vieli, Berner Studien zur Geschichte, Series 1: Climate and Natural Hazards in History, Volume 1. University of Bern 2017, p. 10.

- ↑ The upper limit of the permanent settlements in the Simmental in their dependence on soil structure and agriculture . Paul Köchli, Geographica Helvetica 1947. p. 22.

- ^ Boltigen: a contribution to the historical settlement geography in the Simmental . Robert Tuor, Berner Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Heimatkunde Volume (year): 37 (1975), p. 107.

- ↑ "When the high alpine daughter thunders down into the valley wrapped in her white robes" . The avalanche winter of 1887/1888 in the Bernese Oberland. Isabelle Vieli, Berner Studien zur Geschichte, Series 1: Climate and Natural Hazards in History, Volume 1. University of Bern 2017, p. 14.

- ↑ "When the high alpine daughter thunders down into the valley wrapped in her white robes" . The avalanche winter of 1887/1888 in the Bernese Oberland. Isabelle Vieli, Berner Studien zur Geschichte, Series 1: Climate and Natural Hazards in History, Volume 1. University of Bern 2017, p. 23.

- ↑ "When the high alpine daughter thunders down into the valley wrapped in her white robes" . The avalanche winter of 1887/1888 in the Bernese Oberland. Isabelle Vieli, Berner Studien zur Geschichte, Series 1: Climate and Natural Hazards in History, Volume 1. University of Bern 2017, p. 33.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 344.

- ^ Database of the Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research SLF, extract March 2019.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal . M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 50.

- ↑ COGEAR. MODULES 1a: Historical Earthquakes in the Valais Del. No .: 1a.2.1 . Swiss Seismological Service, January 10, 2010. p. 29

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 360.

- ↑ Geoportal of the Canton of Bern, excerpt from the stages of development of the forest in the Färmeltal. You can also manually select the building via selection as a parameter. Retrieved March 6, 2019 .

- ↑ Regional Forest Plan 22 2006–2020. Obersimmental – Saanen, Office for Forests of the Canton of Bern, Spiez February 2006, p. 4.

- ↑ In the Färmeltal. M. Lempen, E. Bergmann, P. Bratschi, Zweisimmen 2017, p. 340.

- ↑ Article in 20 minutes from January 28, 2019. Living in the “most dangerous place in Switzerland”. Retrieved February 25, 2019 .

Coordinates: 46 ° 29 '24.7 " N , 7 ° 25' 35.3" E ; CH1903: 599,065 / 148765