Free State Bottleneck

A narrow area between the Rhine and the unoccupied part of the Prussian province of Hessen-Nassau , which remained unoccupied during the Allied occupation of the Rhineland from January 10, 1919 to February 25, 1923 after the end of the First World War , was self-deprecating as the Free State of Bottleneck remaining unoccupied Germany was in fact isolated and thus politically and economically on its own. It was not a state in the sense of international law .

Emergence

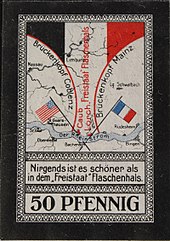

After the war ended, the Compiègne armistice ordered the occupation of the area on the left bank of the Rhine by the Allies and additional bridgeheads at Cologne (British), Koblenz (US) and Mainz (French). Between the US bridgehead at Koblenz and the French bridgehead near Mainz, which each covered a radius of 30 km, a narrow strip between the Rhine Valley and Limburg an der Lahn remained vacant, which has the shape because of its location between two almost touching circular arcs of a bottle neck.

Up until this point in time, the localities in this area were subordinate to the district administrations of the Rheingau district , the Untertaunus district and the St. Goarshausen district , whose sovereignty now ended at the borders of the occupied bridgeheads, so that an emergency arose in the "bottleneck" at this administrative level, which led to self-administration force. This structure was the “Free State of Bottleneck”.

The bottleneck included the places Lorch , Kaub , Lorchhausen , Sauerthal , Ransel , Wollmphia , Welterod , Zorn , Strüth , Egenroth and Laufenselden . There are different figures about the total number of inhabitants: in his 1924 report, Pnicck speaks of around 8,000 souls, while a 1919 letter from the Kassel regional council mentions the number 17,363. Adding up the estimated population at the time is much closer to 8,000.

Bottleneck situation

Isolated location

Not only official and judicial competences from outside the bottleneck were lost. Above all, all existing traffic routes into the region now led through one of the bridgeheads as a result of the narrow border. Therefore, the bottleneck was connected purely geographically with the rest of the unoccupied Germany, but initially there were no more ways by which the bottleneck locations could have been reached - for example from Limburg. All roads were blocked at the borders of the bridgeheads and could only be used with a special pass. Railway trains on the right bank of the Rhine were not allowed to stop. Sometimes not even the bottleneck locations had a usable road connection. The narrowest point was in the wooded area between the villages of Zorn and Egenroth.

Self-management

At first, both the French occupying power and the German administrative offices of the bridgeheads made efforts to close the bottleneck in the occupied area - the first because the bottleneck was strategically and logistically disturbed, and the second out of goodwill because they did not believe that the area could be in his keep isolated position. The inhabitants of the bottleneck put up strong resistance because they wanted to remain free land despite their uncertain situation. Eventually all such intentions were dropped.

With the decree of the High Presidium of Kassel on January 3, 1919, the municipal administration of the area was transferred pro forma to the district administrator of the Limburg district; Limburg an der Lahn was the closest unoccupied district and court town. However, since the bottleneck places, especially its de facto capital Lorch, could hardly be reached from Limburg, the mayor of Lorch, Edmund Anton Pnicck , as representative of the Limburg district administrator Robert Büchting, was given extensive powers to control the region manage. Pnicck was thus the political leader of the bottleneck.

Because of the still relatively isolated economic situation, Pnicck initiated the issuance of its own emergency money , which soon gained considerable value in the occupied neighboring areas.

Connection

Pniceck first built a provisional road through the mountainous and wooded area to Limburg, partly only paved with wooden clubs, and set up a telegraph line with the help of the local telegraph office. It was soon possible to set up a separate postal connection to Limburg by horse-drawn vehicle on the road, which initially ran twice a week and, if possible, also took travelers with it. Under favorable circumstances, the 60 km Lorch – Limburg route was covered in one day. Later the delivery of the mail to Laufenselden, and finally even to Strüth in the bottleneck, could be relocated.

care

The basic supply of the region was initially problematic. Some of the bottleneck towns, including Lorch and Kaub, the largest, had no farms worth mentioning and were dependent on outside food supplies, but the provisional road, on which no fully loaded wagons could drive, did not allow sufficient freight traffic. Many elementary economic goods such as food or fuel were illegally brought into the region, for example by smuggling , often with a Rhine ship that could call at the Lorcher Ufer behind the Lorcher Werth at night without being seen from the French-occupied left bank of the Rhine.

Once a French train with coal from the Ruhr, which was standing in Rüdesheim and was supposed to go to Italy as reparations , was kidnapped by courageous railway workers and driven into the bottle neck, where the coal was distributed to the population for heating.

In his report, Pnicck describes his constant efforts to ensure that the bottleneck residents do not have to go hungry in addition to all other restrictions. In fact, they had considerable capital in the form of wine, which after the difficult initial period resulted in relative prosperity in the bottleneck of trade with the neighboring occupied territories.

The bottleneck from a French perspective

The bottleneck remained a thorn in the side of the French command, mainly because it represented a welcome escape route for escaped prisoners of war from the banks of the Rhine to unoccupied Germany. To make matters worse, the self-confident, but not diplomatically trained Pniceck repeatedly snubbed the French rulers unnecessarily, which always led to sanctions. For example, the validity of the passes with which the boundaries of the bridgeheads could be crossed were severely restricted or the boundaries of the bottleneck were shifted at the narrowest point so that the road to Limburg could only be kept passable by diplomatic intervention by the Limburg District Administrator Büchting. Another aspect was the numerous smuggling activities between the bottleneck and the bridgeheads, which could not be effectively prevented.

The end

On February 25, 1923, a few days after the occupation of the Ruhr , Moroccan auxiliaries of the French army marched into the neck of the bottle, while Pniceck was still in Rüdesheim on the return journey from Wiesbaden. When he found out about it, he set off for Lorch as quickly as possible, which, however, was already taken when he arrived. Pnicck was captured and sentenced by the French military courts to imprisonment for various rebellions, smuggling activities, theft of coal trains and in general for Germany's non-compliance with the reparation conditions, as was Marcus Krüsmann , the then mayor of Limburg an der Lahn. The latter was imprisoned in nearby Koblenz . The inhabitants of the bottleneck continued to offer passive resistance to the French occupation and refused any subordination until the occupation on the right bank of the Rhine was ended in November 1924 after the London conference .

present

Today the term Free State of Bottleneck is used to promote tourism in the region. For this purpose, the "Free State Bottleneck Initiative" was founded in 1994 by winemakers and restaurateurs. Since then, its members have provided wines, sparkling wines and fine brandies with the initiative's seal.

On the banks of the Rhine, tourist signs remind of the historic Free State.

Banknotes from the “Free State of Bottleneck” are sought-after collector's items today.

See also

literature

- Edmund Pnicck: The Free State of Bottleneck: the most grotesque structure of the occupation . Reprint from the “Frankfurter Nachrichten”, 1924. Available online at Webdesign Kaub .

- Stephanie Zibell, Peter Josef Bahles: Free State of Bottleneck: Historical and Little History from the Time between 1918 and 1923 , Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-7973-1144-3 .

- Marco Wiersch , Bernd Kissel : Free State of Bottlenecks (Comic), Carlsen, Hamburg 2019, ISBN 978-3-551-78150-5 .

Web links

- Hessian Bibliography: Free State of Bottleneck , literature listed in the Hessian Bibliography

- Free State Bottleneck

- Bottleneck Free State: State founding in the Rhine Valley One day contribution: Contemporary stories on Spiegel Online

- January 10, 2009 - 90 years ago: The Free State of "Bottleneck" is born , broadcast by Westdeutscher Rundfunk

- Smugglers and smugglers - 90 years ago the "Free State" Bottleneck was founded Contribution by Deutschlandfunk in text form

- City of Lorch: Free State of Bottleneck

- “Free State of Bottleneck”: Bare buttocks flashed in the light of the searchlights

- ZeitZeichen : 01/10/1919 - Free State of Bottleneck is created

- SWR2 foreword: The Free State of Bottleneck is proclaimed

Individual evidence

- ↑ see article discussion

- ↑ According to Pnicck's description, the bottleneck there was narrower than 1 km. The town halls of Koblenz and Mainz (as the centers of the circular arcs) are 62.8 km as the crow flies from each other, which means a minimum width of 2.8 km. On the other hand, the radii were not exactly adhered to in practice.

Coordinates: 50 ° 9 ′ 42.8 ″ N , 7 ° 55 ′ 15.6 ″ E