Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne was signed on July 24, 1923 between Turkey and Great Britain , France , Italy , Japan , Greece , Romania and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in the Palais de Rumine . The venue for the negotiations was Ouchy Castle .

With this treaty, after winning the Greco-Turkish War in 1922, Turkey was able to revise the provisions of the Treaty of Sèvres , which was concluded after the First World War , in part according to its ideas.

The agreement subsequently legalized the expulsion of Greeks and Turks that had already taken place . The current borders of Turkey and Greece have their origins in this treaty.

Content of the contract

The peace talks were initiated on November 30, 1922 by the League of Nations , represented by Fridtjof Nansen . An important intermediate step was the Convention on the Exchange of Population between Greece and Turkey , which was agreed on January 30, 1923 (see below).

According to the treaty, Turkey received Eastern and Southeastern Anatolia (Eastern Anatolia was provided for in the Treaty of Sèvres for Armenia ), Eastern Thrace (since then the European part of Turkey) and Izmir ( Smyrna in Greek ) . Greece kept western Thrace .

Turkey agreed subsequently already on November 5, 1914 proclaimed the annexation of Cyprus to by Britain, up to this agreement Cyprus had heard formal yet with Turkey. Turkey also gave up its claims against Egypt and Sudan .

Furthermore, the Italian occupation around Antalya was revised. In return, the Turkish state recognized Italian sovereignty over the Dodecanese and Libya , which had fallen to Italy as a result of the Ottoman-Italian War .

The treaty used religious affiliation as a criterion for national affiliation and thus for resettlement. In the section on the protection of minorities (Articles 37–45), it regulated the rights of the remaining non-Muslim minorities in Turkey and the Muslim minorities in Greece. In Turkey, Jews, Greeks and Armenians were recognized as minorities. They should have the same civil rights in Turkey as the Muslim Turks.

The Christian Assyrians , who like the Armenians were victims of the genocide of 1915 , were not included in the treaty. Thus the treaty did not provide for minority rights for this indigenous people. Through this treaty the existence of an Assyrian ethnic group is denied to this day.

Convention on the Exchange of Population between Greece and Turkey

The Convention on the Exchange of Population, agreed on January 30, 1923 between Greece and Turkey, was part of the Treaty of Lausanne (under Article 142).

Content of the Convention

On the basis of this convention, the Turkish citizens of the Greek Orthodox faith residing in Asia Minor (mostly native Greeks), but also Turks of the Christian faith (around 1.5 million), were expelled to Greece, the Greek citizens of the Muslim faith (around 0.5 million, mostly native Turks and Greeks who had converted to Islam) had to emigrate to Turkey.

Excluded from the population exchange were a total of 110,000 Greeks in Turkey and 106,000 Turks in Greece:

- the long-established Greek and Greek Orthodox population of Istanbul (officially known as rum ).

- the Western Thrace Turks ( Turks , Pomaks and Muslim Roma east of the border line established in the 1913 Treaty of Bucharest ). As Muslim residents of Western Thrace, you should stay in Greece. Since then, Greece's contact for these three ethnic groups has been Turkey.

- the population of the islands of Imbros / Gökçeada and Tenedos / Bozcaada . (This point was not yet part of the Convention of January 30th, but part of the Main Treaty, Article 14.)

classification

The aim of the population exchange was to reduce the tensions caused by national minorities. In this way, peace should be secured on the basis of clearly defined nationality boundaries. For powerful politicians of the time such as Winston Churchill or Edvard Beneš, as well as for the League of Nations, population exchange was regarded as a paradigm for the peaceful resolution of ethnic conflicts. Greece and Bulgaria had already agreed on a population exchange in the Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine in 1919.

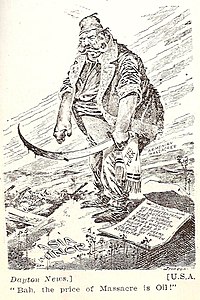

However, the resettlement brought great suffering to those affected: They lost their homeland and were only allowed to take their movable property with them, which was expressly protected by the Convention. Real estate has been liquidated and the owners have been compensated. Many died during the often brutal resettlement measures. Most of the population groups intended for resettlement, however, had already been expelled before 1923 and many members of the minorities were murdered in the process.

The British Foreign Minister and leading representative of imperialism George N. Curzon described the Treaty of Lausanne as "a thoroughly bad and evil solution for which the world will have to pay a heavy fine for the next hundred years".

The population groups officially excluded from the population exchange in Turkey and Greece (see above) could not be protected from discrimination or hostility solely by the Treaty of Lausanne. Many of them also emigrated in the following decades. In Turkey, the Istanbul pogrom (1955) in particular resulted in an expulsion of the Greeks from Istanbul (see also the aftermath of the population exchange between Greece and Turkey ).

Aftermath

In the Treaty of Montreux in 1936, Turkey regained full sovereignty over the straits.

In the 1950s, Turkey unilaterally declared with regard to Cyprus that the Treaty of Lausanne would lapse if something changed in the status of Cyprus. Great Britain had previously declared, in response to Greek attempts at independence on the then British-ruled island, that Cyprus was also a matter for Turkey.

During a meeting with community leaders in Ankara at the end of 2016 , Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan once again questioned the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne. He spoke of "unfair regulations" and a "defeat of Turkey". As an example, he cited the Greek Aegean Islands, which are within "calling distance" of Turkey. There is still a "battle over what a continental shelf" is, "and what borders we have on land and in the air," said the Turkish head of state. He complained that those who sat down at the negotiating table at the time did not do justice to the real circumstances.

After the Greek Minister for Seafaring and Island Policy Nektarios Santorinios announced the settlement of 28 small islands in the Aegean Sea in a letter sent to parliament in the first week of January 2017 , the Turkish Foreign Ministry warned the Greek government against this through its spokesman Hüseyin Müftüoğlu Intention. On January 14, 2017, Minister Santorinios denied a Greek intention to settle and assessed the Turkish warning as interference in the internal affairs of Greece.

Trivia

The Swiss Federal President Pascal Couchepin presented Turkey with the table at which the Treaty of Lausanne 1923 was signed on November 11, 2008 during a visit by the Turkish President Abdullah Gül .

literature

- Karl Strupp (ed.): The Treaty of Lausanne. Text with explanations and a detailed introduction about the development of the reparations problem . Roth, Giessen 1932

- Roland Banken: The Treaties of Sèvres in 1920 and Lausanne in 1923. An international legal investigation into the end of the First World War and the resolution of the so-called "Oriental Question" through the peace treaties between the Allied powers and Turkey . Lit Verlag, Münster 2014, ISBN 3-643-12541-0 .

- Andrew Mango: From the Sultan to Ataturk: Turkey (= Makers of the Modern World: The Peace Conferences of 1919-23 and their Aftermath). House Publishing, 2009, ISBN 1-905791-65-8 .

- Jeremy Salt: The last Ottoman wars: the human cost, 1877-1923, The University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City 2019, ISBN 978-1-60781-704-8 .

- Ferudun Ata: The Relocation Trials in Occupied Istanbul. Manzara Verlag, Offenbach am Main 2018, ISBN 9783939795926 .

Web links

- Text of the Peace Treaty (English)

- Text of the Convention regarding the exchange of Greek and Turkish populations (English)

- Newspaper article about the Treaty of Lausanne in the press kit of the 20th century of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

Individual evidence

- ^ Assyrian rally in Lausanne. | NZZ. Retrieved July 11, 2020 .

- ↑ New Germany editorial team :? Assyrians are demanding their recognition (Neues Deutschland). Retrieved July 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Renée Hirschon: Crossing the Aegean: The Consequences of the 1923 Greek-Turkish population exchange: An Appraisal of the 1923 Compulsory Population Exchange Between Greece and Turkey (Studies in Forced Migration) . New York 2004, ISBN 1-57181-562-7 , p. 6.

- ↑ Christopher Panico: THE TURKS OF WESTERN THRACE . Humans Right Watch. S. January 2, 1999. (PDF; 350 kB) - In 1923, the provisions of the Treaty of Lausanne left some 106,000 ethnic Turks in Thrace. The ethnic Greek minority of Istanbul [...] has also shrunk in size [...] from 110,000 in 1923 to an estimated 2,500 today

- ^ Treaty of Lausanne . January 30, 1923. - The agreements which have been, or may be, concluded between Greece and Turkey relating to the exchange of the Greek and Turkish populations will not be applied to the inhabitants of the islands of Imbros and Tenedos.

- ↑ Renée Hirschon Crossing the Aegean: The Consequences of the 1923 Greek-Turkish Population Exchange: An Appraisal of the 1923 Compulsory Population Exchange Between Greece and Turkey (Studies in Forced Migration) , New York 2004, ISBN 1-57181-562-7 , P. 7.

- ↑ Norman M. Naimark: Fires of Hatred. Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe . Harvard 2001. ISBN 0-674-00313-6 , p. 55.

- ↑ http://www.bpb.de/apuz/32116/historische-hintergruende-des-züstenkonflikts?p=all

- ↑ Ankara questions the Lausanne Treaty - Athens in turmoil . Greece.net.

- ↑ Προκαλεί ξανά η Αγκυρα: Μην τολμήσετε να κατοικήσετε μικρά νησιά ( Greek ) ΗΜΕΡΗΣΙΑ On Line. January 13, 2017. Turkey warns Greece against colonization of 28 Greek islands

- ^ Minister says no plans to settle Aegean islets. H KAΘHMEPINH, online edition, January 14, 2017, accessed on August 5, 2018 . Greek Ministry denies the intention to settle 28 Greek islands