Passage graves in Schleswig-Holstein

The division of the passage graves in Schleswig-Holstein into a north and a south group of megalithic graves was carried out by E. Aner, with the Eider roughly representing the borderline. However, since the megalithic tombs on both sides of the Eider sometimes have similar shapes, the allocation of more disturbed facilities can be controversial. Passage graves consist of a laterally attached passage and a chamber with at least six supporting stones and two cap stones. They originated between 3500 and 2800 BC. BC as megalithic systems of the funnel beaker culture (TBK).

“Neolithic monuments are an expression of the culture and ideology of Neolithic societies. Their origin and function are considered to be the hallmarks of social development ”. According to estimates, the bearers of the funnel beaker culture built almost 30,000 barrows. Over 7,000 large stone graves are known in Denmark, of which about 2,800 have been preserved (in Germany there are about 900 of probably 5600).

Passage graves are (not only) much rarer in Schleswig-Holstein than the simultaneous dolmen types , which also applies to all of the immediate neighboring regions. Whereby basic typological forms that occur in Schleswig-Holstein z. B. are also represented in Denmark, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania or Lower Saxony . However, the oval chamber shape of Schleswig and the trapezoidal barren bed of Holstein are in far fewer numbers. Some of the systems are deepened. Jutta Roß believes that sunk systems probably did not have any hills. Although hills have a stabilizing function, since they are more complex to manufacture than depressions, they also meet other requirements.

North group

The sites of this group reach in Schleswig-Holstein from the Flensburg Fjord to the upper Eider. In the west they are limited to Sylt and the confluence of the Treene and Eider. Only one system of this type ( Langbett Krausort ) is located in Ostholstein near Großenbrode .

- Type 1, which is only represented three times in Schleswig-Holstein, has a (small) polygonal chamber shape, which is far more common in Denmark on the Cimbrian Peninsula . It differs from the polygonal pole (a capstone) in that it has a larger number of two or more capstones that are almost always parallel to the corridor axis. An example of the very small passage grave of this type (with an inclined passage) is the passage grave near Kampen with the Sprockhoff no. 1.

- The enlargement of type 1 leads to type 2, the “oval” or “Nordic passage grave”, which is represented in Schleswig-Holstein with seven systems. The best preserved specimen is the Denghoog from Wenningstedt on Sylt . It has the largest area in Schleswig-Holstein (15.75 m²), the longest covered corridor (5.25 m) and three cap stones. The remaining six systems (including the Idstedt robber cave ) are poorer , especially in terms of their passage lengths.

- The nine type 3 chambers have an approximately rectangular floor plan. They reach lengths of 5.2 m and widths of up to 2.2 m, with up to four cap stones. Their shape varies greatly despite the small number. A subdivision is possible due to the rich occurrence in southern Denmark. Features occurring individually or in combination show the close interlinking with the Danish systems:

- slight bulging of one or both long sides, outward

- in eight of the chambers, a trapezoidal floor plan ( passage grave of Missunde ),

- above-average aisle lengths

- obtuse angular position of the two narrow side girders, as is usually the case with type 1 and 2 (not with the Linden-Pahlkrug complex, but with the passage grave of Archsum on Sylt)

Southern group (Holstein Chamber)

The distribution area of the southern group in Schleswig-Holstein lies south of the Eider, which is only crossed to the north in the direction of Eckernförde Bay . With 58 plants (68%) it is represented twice as strongly as the plants of the northern group.

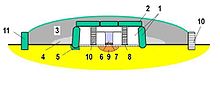

The Holstein Chamber is characterized by an exactly rectangular chamber floor plan. To distinguish them from the facilities of the northern group, they are called "Holstein Chamber" or "North German Long Chamber". Their unprecedented homogeneity does not permit any subdivision. The chamber length is between 3.0 and 8.5 m. Systems up to 5.5 m occur about twice as often as longer ones. Their width varies between 1.0 and 2.25 m. About 60% reach a width of 1.5 m. The systems often have three, sometimes 4-6 cap stones. Typical representatives are Bunsoh and Linden-Pahlkrug .

Accesses

A short corridor consisting of one or two pairs of stones was found in about half of these systems. An eccentric position of the corridor occurs in 40% of the systems (also in the northern group), while the central position (formerly known as the "Lower Saxony Chamber") occurs in 20% (mainly in long chambers). The aisle position is unclear in 40% of the systems. The eccentricity results primarily from the large number of systems with three (or five) supporting stones on the access side, which usually does not allow a central gap.

Further excavations must clarify whether a small number of chambers have no lithically designed access at all (so-called portal graves) as it appears after reconstructions by Ernst Sprockhoff and investigations by Ewald Schuldt (who postulates wooden structures based on post marks).

The type separation

How this clear type separation came about in Schleswig-Holstein was previously explained by the fact that the northern group is regarded as the extension of the southern Jutland passage graves. The construction team theory advocated by Ewald Schuldt and Friedrich Laux offers a new possibility . According to Friedrich Laux, different "building traditions" and "building schools" are behind this dissemination image [2]. On the basis of the technical details, Ewald Schuldt concluded as early as 1972 that the monuments were carried out under the “guidance of a specialist or groups of specialists”.

The origin of the southern group has been explained differently. One has z. B. tries to see an influence that came into the area from Western Europe via Holland and northwest Germany. This thesis contradicts the fact that the facilities of the southern group are probably older than the Emsland chambers . In addition, the specific design of Holstein in Western Europe has no real predecessor. A lateral approach is difficult to derive from Western European systems, although it occurs there in Crec'h Quillé (as well as in Hessian-Westphalian gallery graves - gallery grave of Sorsum ). For the “Holstein Chamber”, most parallels can be found in the south of the Danish islands, where rectangular passage graves with partly eccentric passages dominate. However, in the area of the Danish islands the round hill is more common, whereas in Holstein the long hill is more common. In Ostholstein, in addition to the round and long hill, the D-shaped hill (mostly called a horseshoe-shaped) occurs occasionally ( large stone grave Blankensee , Gowenz). In these systems, the corridor starts from the straight side of the D-shaped hill border. The chamber and corridor of the large stone grave in Blankensee are inclined in the D-shaped enclosure.

Hill and mount

Only 50% of the hills could be determined by shape. The remains of the edging, made of boulders , or, more rarely, parts of dry stone masonry ( Hünenbett Archsum , Osterby) were often preserved. In the western and northern distribution area, round or oval hills predominate. In the east the rectangular or (sometimes only weakly) trapezoidal long hills, each in a ratio of 1: 2. Overall, the number of relatively small round hills (compared to Denmark) is around 45%. Only nine of the systems had a diameter of over 15 m. Mounds in which subsequent burials were carried out were sometimes even elevated or expanded several times and reach a diameter of around 30 m. The mound was poured out of earth, clay, pest or sand. Hills packed with a layer of pebbles , known as a stone coat, which are more common in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (14 of 38 systems examined), are only represented sporadically.

Giant beds

About 130 giant beds can be determined in terms of size. 14 to 40 m long are about 62%. More than 70 m long borders can be found mainly in the eastern half of Holstein. Only 4% of the giant beds are longer than 100 m. A group of these giant beds , 115 and 130 m in length, are the Putlos dolmens near Weissenhäuser Strand , in the Oldenburg-Land department . The largest German system is located in the Sachsenwald in Schleswig-Holstein and measures 154 meters. The longest megalithic bed in Denmark, the Kardyb Dysse, is 185 m long. Almost all of the so-called giant beds contain dolmens or are chamberless . There is only one Holstein chamber in it. Most of them lie in giant beds between 14 and 30 m in length. Beds with two and three, in Denmark occasionally with four to six chambers, are rarely longer than 40 m. In beds with more than one chamber it is noticeable that these are usually of the same type (not in Ostenfelde ). In Archsum on Sylt there are two Urdolmen , in Kampen three polygonal dolms and in 21 other cases two or three ( Hünenbett von Waabs-Karlsminde ) transverse rectangular dolmen are united in the Hünenbett. According to this, the installation of additional chambers seems to have been carried out at a time when the developed designs (apart from the Urdolmen) were still in use (if they ever went out of use). One can explain the length of the giant beds, not the space required for burials. Rather, one must see in them the endeavor to erect an impressive monument, as was the case with the precursors without stone chambers, the up to 200 m long Konens Høj systems .

In contrast to dolmens, Holsteiner Kammern never appear in pairs in a giant bed. In Ostenfeld ( Rendsburg-Eckernförde district ) there is a Holstein chamber together with one of the oblique rectangular dolmen, which are rare in Germany, in the same barren bed. Apparently during the Middle Neolithic in Schleswig-Holstein, unlike in Jutland and on Zealand , there was no need to unite several passage graves within one enclosure.

Individual evidence

- ↑ J. Müller In: Varia neolithica. VI 2009, p. 15.

- ↑ "Schleswig-Holstein is" according to Sprockhoff "the classic land of dolmens in Northern Germany"

- ↑ For Schleswig-Holstein J. Hoika presents figures, according to which about 12% of the small original and rectangular dolms but less than 2% of the passage graves and polygonal dolms are deepened. The other federal states are likely to produce similar figures

- ↑ J. Ross: Megalithic graves in Schleswig-Holstein p. 9.

- ↑ E. Aner 1968, pp. 53-63.

- ↑ by Jacob-Friesen and Aner

- ↑ Similarly, Ewald Schuldt 1972, p. 37f for Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania states that all passage graves with four or six bearing stones have central passages on the access side

- ↑ E. Schuldt 1972, p. 31.

- ↑ A giant bed in Albersdorf (Holstein) with 160 meters is often called the longest in Germany. This error is based on an incorrect statement in Ernst Sprockhoff's Atlas of Megalithic Tombs in Germany - Schleswig-Holstein . The megalithic bed is actually only 60 meters long, and is also recorded as LA53 in the state survey.

- ↑ J. Roß 1992, p. 175: “Since the construction of megalithic tombs cannot be rationally justified or explained, we have to assume the background in the area of religious ideas. Presumably, megalithic graves were not only burial sites, but also had a function and meaning in religious or cultic life "

- ↑ J. Roß p. 56 “in exceptional cases like the Ostfeld dolmen the access is at a corner of the chamber” (this form is more common in Sweden)

See also

literature

- E. Aner: The great stone graves of Schleswig-Holstein. In: Guide to Prehistoric and Protohistoric Monuments. 9/1968, pp. 46-69.

- V. Arnold: Small gravesite of the prehistory. Part 1: Large stone graves from the peasant days. In: Leaves for local history. 1 supplement to the magazine "Ditmarschen" 1977.

- E. Schuldt : The Mecklenburg megalithic graves . German Science Publishing House, Berlin 1972.

- J. Ross: Megalithic graves in Schleswig-Holstein . Hamburg 1992, ISBN 3-86064-046-1 .