Mortuary temple of Hatshepsut

| Mortuary temple in hieroglyphics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18th dynasty |

Djeser-djeseru ḏsr-ḏsrw Most Holy of the Most Holy |

|||

| Mortuary temple of Hatshepsut | ||||

The mortuary temple of Hatshepsut dates from the 18th dynasty and is the best preserved temple in Deir el-Bahari on the west bank of the Nile in Thebes . Its idiosyncratic architecture is striking. The pylons have been replaced by open pillar halls at the beginning of each terrace. The entire temple is made of limestone .

The entire valley basin of Deir el-Bahari is mainly dedicated to the gods Hathor and Amun-Re , as well as Horus in Chemmis , Anubis , Amun and Iunmutef . The temple was used until Ptolemaic times. In Coptic times, the Phoibammon monastery was built on the temple . The monastery was used until the 11th century and was visited by various bishops. The mortuary temple of Hatshepsut is a so-called million year house .

history

The temple was built within 15 years, from the 7th to the 22nd year of Queen Hatshepsut's reign. The steward Senenmut is seen as an architect , as indicated by various hidden representations of Senenmut and the existence of the unfinished grave planned for him ( TT353 ) under the first terrace. Despite the many speculations about the relationship between Senenmut and Hatshepsut, the exact position he held at court and the reason why he was not later buried under the temple are unknown. In addition to Senenmut, Hapuseneb , Nehesy , Djehuti and Minmose were involved in the construction of the temple, which is evidenced by the name stones that were built into the temple and the ramps. During the Damnatio memoriae , which also affected Queen Hatshepsut, the temple was badly damaged. Many wall representations and statues were destroyed.

In the 19th century Auguste Mariette carried out the first soundings here, but not documented them. Only Édouard Naville , who worked in Deir el-Bahri for the British Egypt Exploration Fund from 1893 to 1897 and from 1903 to 1906, cleared the fallen boulders and the Coptic monastery in the first two winters in order to move to the temple parts that had been buried under the rubble of thousands of years to get. Howard Carter , also employed by the EEF, copied the paintings and inscriptions with other artists. Naville documented his work in detail in seven volumes: The Temple of Deir el Bahari. (= Egypt Exploration Fund. [EEF], Vol. 12-14, 16, 19, 27, 29). 7 volumes, London, 1894–1898.

Later excavations were carried out between 1911 and 1931 by Herbert E. Winlock for the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Émile Baraize for the Egyptian Antiquities Service, documented in "Herbert Winlock: Excavations at Deir el Bahri: 1911-1931 , 1942".

Some of the pillars destroyed during the Damnatio memoriae were found and reconstructed in a nearby quarry in 1934 by an expedition from the Metropolitan Museum of Art from New York .

From 1961 Zygmunt Wysocki and Janus Karkowski carried out reconstruction and restoration work for the Polish Center of Mediterranean Archeology at the University of Warsaw in collaboration with the Supreme Council of Antiquities .

Assassination attempt on November 17, 1997

In an attack on the temple grounds on November 17, 1997, 62 people lost their lives. Most of them were Western tourists, 36 of them Swiss.

architecture

Temple

map of Deir el-Bahari (I) Temple of Mentuhotep II. (1) Bab el-Hosan

(2) Indoor vestibule

(3) Terrace with colonnade

(4) Tumulus

(5) Hypostyle

(6) Sanctuary

(II) Temple of Thutmose III.

(III) Temple of Hatshepsut

(7) Courtyard

(8) First Portico

(9) First Terrace

(10) Second Portico

(11) Hathor Chapel

(12) Anubis Chapel

(13) Festival Courtyard of the Second Terrace

(14) Amun Shrine

(15) Sun temple with a small Anubis chapel

(16) Sanctuary of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III.

From the temple complex, the approximately one kilometer long processional road leads east to the valley temple of Hatshepsut on the edge of the fruiting land. From the valley temple on to the Nile and on the other side of the river to the temple of Amun-Re in Karnak. The processional street was originally lined with sphinxes on both sides . The sphinxes were made of sandstone and came from the Jabal al-Silsila quarry .

Portico and terraces

In the idiosyncratic temple architecture differs from the classical temples 1. pylon → Hof → 2. pylon → Hof → portico made that the classic pylons through here portico have been replaced (pillar halls) and the subsequent farms in terraces upward and connected by ramps.

From the east one reaches a large courtyard via the approx. One kilometer long processional street, on the west side of which is the first portico (position 8 on the map), a pillar hall made up of two rows of pillars. This is open to the east and there is a colossal statue of Hatshepsut on both sides of the portico . The first portico consists of the obelisk hall, to the left (south) of the ramp. It bears this name because the wall representations mainly show the production in Aswan , the transport and the erection of two obelisks in the Karnak temple . The right (northern) hall is known as the hunting hall, as it mainly depicts hunting scenes from the hunt for waterfowl and fish.

In the middle a ramp leads to the first terrace. Again on the west side of this terrace is the second portico (position 10 on the map), this is also open to the east and there is also a ramp to the second terrace here in the middle. The second portico on the left consists of the punt hall , in which the wall paintings depict a trade expedition to Punt in the ninth year of Hatshepsut's reign (either according to Helck: approx. 1459 BC or according to Krauss: approx. 1471 BC) and on the right the birth hall, in which the divine birth of Hatshepsut is depicted. The Hathor Chapel (position 11) adjoins the Punch Hall on the left and the Anubis Chapel on the right (position 12).

The second terrace is opened directly by a portico through which one can access the terrace. At the front there are 26 statues of Hatshepsut, some of which are very well preserved. The north and south walls are decorated with ritual runs of the king. The west wall was decorated with a larger text under Hatshepsut, which under Thutmose III. was replaced by other reliefs. A granite gate in the third portico leads to the terrace. From the central courtyard (position 13) of this terrace you can go straight ahead to the main sanctuary of Amun-Re (position 14), on the right to the solar sanctuary (position 15) and the southern chapel of Amun-Re and on the left to get to the chapels of Hatshepsut and of Thutmose I (position 16), to the northern chapel of Amun-Re and into a room with a window, the function of which has not been clarified. The central courtyard of the second terrace is also known as the festival courtyard. The wall depictions show the procession at the valley festival from Karnak to the temple. In the walls of the courtyard there are various niches in which statues of Hatshepsut stood.

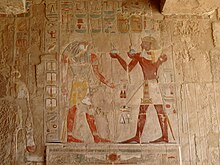

The Hathor Chapel

To the left of the Punch Hall there is a small portico in front of the Hathor Chapel. The central columns are adorned with Hathor capitals. This portico opens into a vestibule on the inside , through which one reaches the portico of the chapel. The right wall of the vestibule shows a figure with Hathor, shown as a cow. In the adjoining portico, the right wall is decorated with a representation of a procession of soldiers with their boats. The back wall with the entrance to another vestibule of the chapel is decorated with depictions of the Hathor cow licking Hatshepsut's hand and adorned with ritual running scenes, on the left the bird run and on the right the oar run.

In the first room of the chapel, the representation on the left wall shows Weret Hekau sacrificing a menit . On the wall opposite the entrance you can see a Hathor standard and on the lintel the royal titles of Thutmose II and Thutmose III. In the top two lines the gate is referred to as the door of Hatshepsut (changed to Thutmose III). On the two horizontal columns on either side of the door it is written that Hatchepsut (changed to Thutmose III) built the temple for her mother Hathor, colonel of Thebes (picture). On the left wall you can see Queen Hatshepsut in front of the goddess Hathor and on the entrance wall (changed to Thutmose III) playing a ball in front of the goddess. There are four niches in the next room. Behind it is a small room with a depiction of Hatshepsut (changed to Thutmose III) being hugged by Hathor before Amun. In a small adjoining room on the left there is a portrait of Senenmut.

The Anubis Chapel

The actual sanctuary is located behind the portico of the Anubis Chapel . The portico contains 12 columns. Anubis and Hatshepsut were depicted on the right side wall, but this depiction was destroyed. Further back on the right wall there are depictions of Osiris , Re-Harachte , Nechbet and Hatshepsut. On the wall opposite the open side of the portico, to the left of the passage to the next room, there is a scene of sacrifice in which sacrifices are made to Amun. To the right of the passage is a scene of sacrifice in which Anubis offerings are made. The portico has a niche to the right and left. The right niche is with a representation of Sokar and Thutmose III (picture). adorned. From the portico there is a small elongated room, at the end of which there is an equally elongated room on the right, which has a niche at the back left.

Another chapel dedicated to Anubis is located north of the Sun Sanctuary and can be reached through it. It is a small chapel with little wall decoration.

Sun sanctuary

The solar sanctuary consists of an open courtyard and a large solar altar that is accessible via a staircase. A vestibule leads from the third terrace into the courtyard of the solar sanctuary. The walls of the solar sanctuary were not decorated. The night travel of the sun from sunset to sunrise is depicted on the walls of the vestibule.

Chapel of Hatshepsut and Thutmose I.

The sanctuary of Hatshepsut is the largest sanctuary in the temple, along with the main chapel of Amun. On the side opposite the entrance there is a false granite door . A vaulted ceiling forms the roof. Almost nothing is left of the original rich decoration. Through the vestibule, through which one arrives in the sanctuary of Hatshepsut, one also arrives in the sanctuary of Thutmose I. Here, too, hardly any decoration has been preserved.

Chapels of Amun-Re

A large granite gate leads to the first room of the Amun-Re sanctuary. In this room of the main chapel there are two statues of Hatshepsut, unfortunately their heads are missing, two other statues are occupied but not preserved. The other rooms of the sanctuary can be reached through the rear door of the room. At the time of Hatshepsut, the procession of the valley festival ended in this room . The room is covered by a vaulted ceiling and has four niches. Above both doors there is a small window through which the sun's rays used to shine into the sanctuary and thus shine on the statue of Amun-Re.

The northern chapel of Amun-Re consists of a small, elongated room. The back wall shows a wall representation of Amun-Re in an embrace with Thutmose II. Sacrificial scenes are shown on the side walls.

The southern chapel of Amun-Re consists of a small and almost square room; scenes of sacrifice have been preserved on the walls.

literature

(sorted chronologically)

General overview

- Édouard Naville : The Temple of Deir el Bahari. Part III, Egypt Exploration Fund, London 1898; Part IV, London 1901.

- Dieter Arnold : The temples of Egypt. Artemis & Winkler, Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-86047-215-1 , pp. 134-38.

- Wolfgang Helck : Small Lexicon of Egyptology. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-447-04027-0 , ( Deir el-Bahari pp. 65–66, Hatchepsut p. 119, Senenmut p. 275–276)

- Rosanna Pirelli: Deir el-Bahri, Hatshepsut temple. In: Kathryn A. Bard (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 , pp. 234-37.

- Dieter Arnold: Lexicon of Egyptian architecture. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2000, ISBN 3-491-96001-0 , pp. 98-99.

- Kent R. Weeks , Araldo de Luca: In the Valley of the Kings: Of funerary art and the cult of the dead of the Egyptian rulers. Weltbild, Augsburg 2001, ISBN 3-8289-0586-2 , pp. 66–75.

Questions of detail

- Jens DC Lieblein : The inscriptions of the temple of Dêr-el-bahri . In: Heinrich Brugsch , Ludwig Stern (ed.): Journal for Egyptian language and antiquity . Twenty-third year. Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung, Leipzig 1885, p. 127–132 ( digitized [accessed April 11, 2016]).

- Herbert E. Winlock : Excavations at Deir el Bahri: 1911-1931. Macmillan, New York NY 1942.

- Rainer Stadelmann : Temple palace and apparition window in the Theban mortuary temples. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. (MDAIK) Vol. 29 , von Zabern, Mainz 1973.

- Peter F. Dormann: The Monuments of Senenmut. London / New York 1988, ISBN 0-7103-0317-3 .

- Zygmunt Wysocki: The Temple of Queen Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari: The Raising of the Structure in View of Architectural Studies. In: MDAIK Vol. 48 , von Zabern, Mainz 1992, ISBN 3-8053-1294-6 , pp. 233-254.

Phoibammon monastery

- Włodzimierz Godlewski: The monastère de St. Phoibammon (= Deir El-Bahari / Center d'Archéologie Méditerranéenne de l'Académie Polonaise des Sciences et Center Polonais d'Archéologie Méditerranéenne dans la République Arabe d'Égypte au Caire. Vol. 5). Ed. Scient. de Pologne, Warsaw 1986.

- Bibliography: Deir el-Bahari.

Web links

- Karl H. Readers: Maat-ka-Ra Hatshepsut. www.maat-ka-ra.de, December 1, 2005, accessed on March 5, 2012 .

- Anja Semling: Ancient Egypt - Kingdom of the Pharaohs. www.mein-altaeggypt.de, January 26, 2010, accessed on March 5, 2012 .

Individual evidence

- ^ D. Arnold: Lexicon of Egyptian architecture. P. 98

- ^ W. Godlewski: The monastère de St. Phoibammon. Warsaw 1986, p.

- ↑ a b c d D. Arnold: The temples of Egypt. Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1996, ISBN 3-86047-215-1 , pp. 134-138

- ↑ a b Alberto Siliotti: The Valley of the Kings. Müller, Erlangen 1996, ISBN 3-86070-607-1 , p. 100

- ↑ Alberto Siliotti: The Valley of the Kings. P. 100

- ↑ Zbigniew Szafrański (Editor): Królowa Hatszepsut i jej Świątynia 3500 lat później. = Queen Hatchepsut and her Temple 3500 years later. Warsaw University Polish Center of Mediterranean Archeology in Cairo / Agencja Reklamowo-Wydawnicza A. Grzegorczyk, Warszawa (Warsaw) 2001, ISBN 83-88823-75-2 .

Coordinates: 25 ° 44 ′ 18 ″ N , 32 ° 36 ′ 28 ″ E