Thermal spring

A thermal spring is a spring from which groundwater emerges, which is usually significantly warmer than the surrounding near-surface groundwater. In Germany, groundwater is defined as thermal water if its temperature at the point of discharge is more than 20 ° C.

Origin, occurrence

Thermal springs generally occur in areas with increased volcanic activity (e.g. Japan, Taiwan, Iceland) and / or in the vicinity of deep-reaching current systems (e.g. Aachen , Baden-Baden ). The water is heated underground, either through volcanic activity or by the water circulating down to deeper areas of the earth and heating up there according to the geothermal depth . The hottest springs in Europe in Bad Blumau (deep borehole) reach 107 ° C, Bad Radkersburg (deep borehole) 80 ° C, Chaudes-Aigues (France, natural spring) 81.5 ° C, Aachen (natural spring) 74 ° C, in Carlsbad (natural spring) 72 ° C and Wiesbaden (natural spring) 66 ° C. In volcanogenic areas, the water temperature is sometimes close to the boiling point . It should be noted that the boiling point of water depends on the sea level (the air pressure ) and the amount of dissolved substances (see there ) and that the water temperatures given above are sometimes not comparable with one another. When ascending to the earth's surface, various gases, such as sulfur gases or carbon dioxide , are usually released.

The area with the world's largest concentration of hot springs on land is the Upper Geyser Basin in Yellowstone National Park ( USA ). 62% of all hot springs (with the exception of the oceans) are there. The most extensive system of thermal springs exists at the ocean floor in the mid-ocean ridges . Iceland, part of the Central Ocean Ridge, is also known for its many hot springs.

coloring

Sintered deposits can often be observed at the immediate exit point from hot springs , which, depending on the chemical structure of the thermal water , can be colored from white to gray ( lime ), light yellow, orange and brown (depending on the iron content) to black ( manganese ). In addition, depending on certain water temperatures, microorganisms such as algae and bacteria ( e.g. cyanobacteria or Thermus aquaticus ) can discolour the water or the sintered heels. The color that is caused by many such microorganisms changes from light yellow to orange to dark green.

Communities

Thermal springs are generally poor in species. Basically, one can say that "normal" aquatic animals and plants cannot survive permanently at temperatures of over 30 ° C. Thermal springs are therefore populated by specialized communities. The limit values up to which specialized aquatic organisms can adapt to heat vary widely. In beetles and rotifers , the extreme limit is 45–49 ° C. Blue algae can tolerate up to 69 ° C, thread-like bacteria ( Chlamydothrix thermalis ) up to 77.5 ° C. Boiling thermal springs are largely free of organisms on the earth's surface. However, hot springs at the bottom of the deep sea can still be colonized by bacteria at much higher temperatures, since the water does not boil at the high ambient pressure (see below). Particularly unique communities can be found here that have only recently been researched (see black smokers ).

Hot water also contains little dissolved oxygen , whereas the high temperature greatly increases the oxygen demand of most organisms. Many organisms therefore suffer from a lack of oxygen. However, some species solve this problem by surfacing to breathe, such as water lung snails or water beetles .

Many thermal springs also contain dissolved hydrogen sulfide , which reacts with dissolved oxygen and thus further reduces the oxygen content. For many organisms, hydrogen sulfide is poisonous in and of itself. However, numerous bacteria (e.g. Beggiatoa arachnoidea , Thiotrix nivea ) and some blue-green algae ( Spirulina sp. , Oscillatoria chlorina ) are not only able to endure hydrogen sulfide, but even use it as an energy source for their own growth. Such organisms are usually found in abundance in sulphurous thermal springs. Some green algae such as Cosmarium laeve cannot use hydrogen sulphide, but they can tolerate it and can therefore also be found in sulfur springs. Against this background, hydrothermal vents are also discussed in connection with the origin of life on earth.

In the course of a thermal spring there are usually more moderate and much more favorable conditions. The water is warm, but no longer hot, oxygenated by movement, and there are no seasonal temperature fluctuations. Therefore, in the runoff of thermal springs in the temperate zone, species are sometimes found that otherwise only occur in the subtropics or tropics. In the thermal spring in Baden near Vienna, this applies to the snail Physa acuta or the grass Cyperus longus .

Special hot springs

The geyser is a special type of hot spring in which the water is pushed upwards like a fountain at regular or irregular intervals and splashes upwards. Fumaroles are hot springs where the water escapes in the form of steam . If the emerging water is mixed with mud and clay, it is called a mud pot .

If the water from a thermal spring mixes underground with cooler groundwater influenced by precipitation, a warm spring is created.

Almost all hot springs in the world contain fresh water. The only three (known) hot salt water springs are found in Italy on Vesuvius , on the Japanese island of Hokkaidō and on the Taiwanese island of Lü Dao ("Green Island").

Sources at the bottom of the deep sea

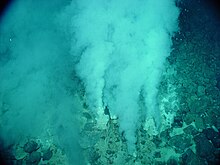

In the deep sea there are several very towering and volcanically active mountains. They form an earth-spanning network that is tens of thousands of kilometers long. Thermal springs with temperatures of more than 400 ° C can be found on these mid-ocean ridges . They are created by sea water that penetrates the earth's crust and flows out again heated. The so-called black and white smokers , tubular or conical chimneys, from which the hot water emerges together with a cloud of sediment, form on the seabed from precipitated minerals .

Thermal springs can also arise on the sea floor through an exothermic chemical process, serpentinization , and are therefore not tied to the mid-ocean ridges. Such a source was first discovered in 2000 ( Lost City , with temperatures between 40 ° C and 90 ° C).

use

Hot and warm springs are popular for therapeutic purposes because they are richer in dissolved minerals than cold springs. Hot and warm springs were already known to the Indians of North America over 10,000 years ago and were used as healing sites. The Jordan Spring in Bad Oeynhausen was drilled in 1926 and, with a depth of 725 m and a discharge of 3000 l / min, is the largest carbonated thermal brine spring in the world. The Aachen and Wiesbaden thermal springs are also among the most productive thermal springs in Germany . These springs often led to the construction of thermal baths . In Wiesbaden, the New Town Hall and two residential complexes are also heated with thermal water.

Thermal springs can also be used as energy sources . From geothermal energy in Iceland the primary energy in the country obtained, for example over 50 percent. The Bláa Lónið (Eng. Blue Lagoon ) is an artificial hot spring that is fed with the waste water from a geothermal power plant. It is a popular tourist attraction on the Reykjanes Peninsula.

See also

Other post-volcanic or thermal spring-related phenomena:

literature

- Mariano Messini, GC Di Lollo: Acque minerali del mondo, catalogo terapeutico. Società Editrice <Universo>, Roma 1957.

- Gerald A. Waring: Thermal Springs of the United States and Other Countries of the World - A Summary Geological Survey. Professional paper. Vol. 492. Washington 1965. ISSN 0096-0446

- Miroslav Malkovsky: Mineral and thermal waters of the world. A-Europe - proceedings of symposium II. International Geological Congress: Report Of The Twenty-Third Session Czechoslovakia 1968. Academia, Prague 1969.

- Miroslav Malkovsky: Mineral and thermal waters of the world. B-Oversea Countries - proceedings of symposium II. International Geological Congress: Report Of The Twenty-Third Session Czechoslovakia 1968. Academia, Prague 1969.

- Walter Carlé : The mineral and thermal waters of Central Europe. Books from the journal Naturwissenschaftliche Rundschau. 2 vols. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, Stuttgart 1975. ISBN 3-8047-0461-1

- Geothermal Energy and Vulcanism of the Mediterranean Area. International Congress on Thermal Waters Oct. 1976. Proceedings THERMAL WATERS. Vol. 2. National Technical University, Athens 1976.

- Jost Camenzind, Hans Peter Treichler , Otto Knüsel, Lilian Jaeggi-Landolf, Hansjörg Schmassmann: Thermal baths in Switzerland. Offizin, Zurich 1990. ISBN 3-907495-11-X

- Björn Hróarsson, Sigurdur Sveinn Jóhnsson: Geysers and Hot Springs in Iceland. Mál og menning, Reykjavík 1992. ISBN 9979-3-0387-5

- Josef Zötl: The mineral and medicinal waters of Austria. Geological foundations and trace elements. Springer, Vienna 1993. ISBN 3-211-82396-4

- Gerd Michel: Mineral and thermal waters. General balneogeology. Hydrogeology textbook. Vol. 7. Borntraeger, Berlin 1997. ISBN 3-443-01011-3

- Sally Jackson: Hot springs of New Zealand. Reed Publishing, Birkenhead Auckl 2001. ISBN 0-7900-0814-9

- Marjorie Gersh-Young: Hot Springs and Hot Pools of the Southwest. Jayson Loam's Original Guide . Aqua Thermal Access, Santa Cruz 2004. ISBN 1-890880-05-1

- Marjorie Gersh-Young: Hot Springs & Hot Pools Of The Northwest . Aqua Thermal Access, Santa Cruz CA 2003. ISBN 1-890880-04-3

- Glenn Woodsworth: Hot springs of Western Canada, a complete guide . Gordon Soules Book Publishers, West Vancouver 1999. ISBN 0-919574-03-3

- Elsalore Fetzmann: The biology of the Baden thermal baths . Communications from the Austrian Sanitary Administration, Vol. 59, 1-4. 1958.

- Löhnert et al. (1992) Thermal waters in the Mygdonias Basin (Northern Greece). The Earth Sciences; 10, 3; 73-78; doi: 10.2312 / geosciences . 1992.10.73 .

- Allen Pentecost: Travertines. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg 2005, 445 pages (English)

Web links

- Submarine hydrothermal vents

- Directory of all thermal baths in Germany

- Directory of natural thermal springs

Individual evidence

- ↑ But there are also thermogenic sources (and fossil sources) that extend into the earth's crust, but whose water has cooled down to "normal" water temperatures at the top. Compare with A. Pentecost, literature list

- ↑ Deutscher Heilbäderverband eV: Definitions: Quality standards for the rating of health resorts, recreation areas and wells . 12th edition, Bonn, 2005

- ^ Bad Blumau Heizkraftwerk ( Memento from October 2, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (August 27, 2009).

- ^ Bernhard Maximilian Lersch : Hydro-Physik, Berlin 1865, available here at Google Books.

- ↑ William Martin: Hydrothermal vents and the origin of life . Biology in our time 39 (3), pp. 166-174 (2009), ISSN 0045-205X .

- ^ New Hydrothermal Vents Discovered As "South Pacific Odyssey" Research Begins .

- ^ Hydrogen And Methane Sustain Unusual Life At Sea Floor's 'Lost City' .

- ^ Jordansprudel in Bad Oeynhausen ( Memento from October 26, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (accessed on October 18, 2014).

- ^ Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung: Energy from 26 hot springs - Wiesbaden heats with thermal water