Chain shipping on the Neckar

The chain boat trip on the Neckar was a special type of Towing, at the chain steamer covered with several attached barges along a laid in the river chain. It was used from 1878 between Mannheim and Heilbronn , from 1884 to Lauffen . The chain shipping reduced the transport costs of the skippers compared to the hitherto customary towing with horses and made ship transport competitive with the railroad again. Due to the increasing canalization of the Neckar and the necessary barrages, the chain towing operation was made difficult and uneconomical. It was increasingly replaced by tugs with propellers and discontinued when the Neckar was completely expanded in 1935.

The situation before chain shipping

The river

The current conditions of the Neckar varied significantly along the course of the river. On the approximately 113 km long stretch of river from the port in Heilbronn to the confluence with the Rhine, river sections with a steep gradient of 1: 350 and shallow sections with a gradient of only 1: 10,000 alternated. If you refer to places with a gradient of more than 1: 700 as rapids, this affected around 7% of the route, i.e. around 7840 m. In addition to the difficulties of gradient variation, there were strong bends in the course of the river.

The bed of the river consisted mostly of limestone and red sandstone . however, rock thresholds were present in some places along the river. The water levels of the Neckar varied greatly depending on the season and the amount of precipitation. The highest water levels were between 6.6 and 14.6 m, depending on the river section, while the Neckar fell below 0.56 m at low water in summer. In the very dry year of 1865, water levels below 0.56 m were measured on 210 days, whereas this low was only reached on one day in 1869. The low water levels significantly hampered shipping. In addition, there was a handicap from frost with an average duration of three weeks in winter.

The flow speed of the water was depending on the gradient and the water level in the rapids area between 1 and 3 meters per second. The river conditions were therefore not particularly favorable for the conditions at the time, but neither were they excessively obstructive.

The ship transport

Until the 18th century, ships were traditionally transported on the Neckar by people who pulled their boats uphill from land on towpaths . Down the valley the boatmen let their boats drift with the current. With the expansion of the transport capacities, the ships got bigger and bigger and shipping was dependent on towing with horses. A typical ship consisted of a main ship with a mast, an anchor tack and a row tack. The load distributed over the three boats was typically around 120–150 t . The crew consisted of the ship owner, two sailors and a cabin boy. In addition, there were six to ten draft horses drawn one behind the other, which were ridden by four to five leash riders.

Every day around 20 km could be covered in 5 hours, so the distance from Mannheim to Heilbronn took around 5.5 days. The horses had to be transferred from one bank to the other in five places, and additional harness horses were required in individual places. The wages for the riders were negotiated individually with the ship owner and varied depending on the water level and demand. The operating costs could therefore hardly be planned. It was not until 1863 that contracts with a term of one year each were concluded. However, these could not prevent a steady rise in costs. For the most part, the proceeds from the freight barely covered the transport costs. The ascent was partly in deficit and could only be partially compensated for by the descent.

The main transport goods to Berg were coal and colonial goods, and to Tal the cargo consisted primarily of cooking and rock salt from the Friedrichshall and Wimpfen salt works , construction timber and timber, stones from the Odenwald quarries and grain. The total transport volume on the Neckar in Heilbronn increased significantly from 25,600 t (1836) to 79,600 t (1854) to around 115,000 t (1872). At the same time, the railroad created increasingly clear competition for boatmen. The expansion of the railway routes took place mainly on the routes Mannheim– Heidelberg (1840), Heidelberg– Neckargemünd - Meckesheim - Neckarelz - Mosbach (1862), Meckesheim– Rappenau (1868) and Rappenau– Jagstfeld (1869). The train offered cheap prices and high speed. For the skippers, lower income was offset by ever higher costs, so that it was feared that shipping could come to a complete standstill in a few years.

The first attempts to switch shipping to steam operation were made in 1841 with a paddle steamer . However, this failed due to the difficult conditions on the Neckar. The low water level, the tight bends and the strong current in the area of the numerous rapids made it impossible or at least unprofitable, depending on the water level.

Chain shipping

Planning and concession

Due to the increasing competition from the railroad , the Heilbronn merchants saw the importance of their town as an important trading center at the end of the navigable Neckar endangered and looked for an economical means of transport by water. Without shipping as the only competitor to the railways, price increases would have been foreseeable. In addition, the danger of a railroad traffic monopoly had shown during the Franco-German War (1870–1872). Due to the militarily stressed railroad, the civil transport of goods by land came to a standstill and could only be maintained by shipping.

As a result, the Heilbronn commercial director founded a provisional committee in 1872 to introduce chain shipping on the Neckar. To investigate the situation on the Neckar, the committee resorted to the help of the director of the chain towing shipping of the Upper Elbe , engineer Ewald Bellingrath , the road and hydraulic engineering inspector von Martens from Stuttgart, and Max Honsell as a member of the Baden regional directorate for hydraulic engineering and road construction. All three came to the conclusion that chain shipping alone, as it had been practiced on the Elbe since 1866, would be advantageous on the Neckar from a technical and financial point of view. With this technique, chain steamers pull themselves together with an attached tow tractor along a steel chain sunk in the river. The cable boat trip , however, is unsuitable due to the shallow water and the tight curves.

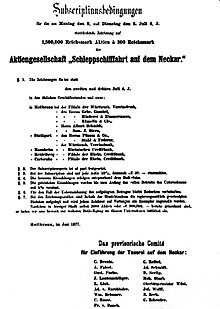

On October 2, 1872, the committee applied for a concession for chain shipping from the Württemberg government, which then began official negotiations with the governments of the two other riverside states of Baden and Hesse. When the concession was in prospect at the end of 1873, however, there were problems in raising the necessary share capital. Due to the general economic development of the last two years, a lot of free capital was tied up in companies and the willingness to invest in new projects was low. For this reason the committee asked for a grant or at least for the assumption of a state guarantee by the Württemberg royal family. In a corresponding letter from Heilbronn mayor Karl Wüst , he emphasized in May 1874 that the future of Heilbronn depends on the preservation of shipping and that the state of Württemberg, as the owner of salt pans and forests, should have a clear interest in competitive shipping on the Neckar.

The guarantee law passed on July 1, 1876 provided for the assumption of a state guarantee for a stock corporation for the establishment of chain and cable shipping on the Neckar by the Württemberg state. The state guaranteed to grant an annual subsidy of up to 5% of the paid-in share capital for a period of 20 years if the company's annual income was insufficient to cover operating costs and a five-percent dividend for the shareholders. At the same time, the corporation undertook to repay subsidies made earlier if the net profit was greater than 6%. If earlier grants are not to be reimbursed, the state is to share 50% of the surplus.

In the summer of 1877 a subscription of five percent shares could be fixed. The city of Heilbronn acquired 500 of the 6000 shares offered, each with a nominal value of 300 Reichsmarks. After securing the share capital , the board of the stock corporation headed by businessman Louis Link and Karl Wüst , who has meanwhile been appointed mayor, was elected at the constituent meeting of tug shipping on the Neckar AG . In the same year, the company received the 34-year concession from Hesse (August 27), Baden (September 22) and Württemberg (November 1). The content of the concessions with the same name was in particular the endeavor to prevent unilateral preferential treatment of individual ships. All vehicles suitable for towing should be transported in the order in which they were registered. The tariff for the transport was to be determined in consultation with the ministry. This was divided into a fee for hauling the empty boat and a weight-dependent part for the cargo.

business

On May 23, 1878, near Wimpfen, a richly flagged tow train, the chain ship No. I with a train of empty Neckar vehicles for the probably over 500 invited guests, was ready for the festival trip. Among the guests were State Minister von Sick as well as other high-ranking officials and members of parliament from the neighboring countries. The following day the chain steamer drove to Mannheim. From there he started his first real towing journey with nine barges attached (total load 360 t) and reached Heilbronn on May 27th. The travel time was reduced by about half compared to the horse-drawn train. At the same time, the costs were significantly reduced. Shipping became competitive again. On June 15, 1878, King Karl I visited the facility and drove from Neckarsulm to Heilbronn. In the months that followed, a new chain steamer was put into service until September. The fifth chain steamer was added in 1880.

The boatmen quickly adopted the new chain towing service. From 1878 to 1883, the number of vehicles towed and the cargo transported increased steadily. In the mid-1880s, mountain traffic on the Neckar was roughly doubled compared with the mid-70s, although the new railway lines Neckargemünd- Eberbach- Neckarelz-Jagstfeld (1879) and Jagstfeld-Heilbronn (1882) went into operation. The returns paid out to the shareholders were between 5.5 and 6.6% with increasing income of the company. In 1884 there was a slight drop in shipping traffic. Due to a prolonged, extreme drought, the water level was very low all year round and twice reached its lowest level of only 45 cm. Not only the low rainfall, but also the water withdrawal by farmers and the damming of the waterworks at night ensured that the chain tugs had to interrupt their journey again and again due to lack of water. Coal and cables from the chain steamers were moved as far as possible to tender ships in order to reduce the draft. In this way, shipping operations could be maintained down to a minimum water depth of 50 cm.

The tug shipping company ensured with its pricing while maintaining its own profitability that the skippers could offer their services at competitive prices to the railroad and at the same time had a reasonable income. For example, it gave the boatmen discounts at low water levels. The state of Württemberg itself had an interest of its own in promoting trade on the Neckar. The income from the trade in Heilbronn as well as the income from the chain towing service benefited the state of Württemberg directly. This led to the fact that shipping was preferred at the same cost and so the Württemberg State Railroad was instructed to transport its coal by ship to Heilbronn. For this purpose, the tug shipping company in Heilbronn built three steam cranes specifically to unload the ships.

After a chamber of the Wilhelm Canal Lock, built in 1821, was enlarged to 48 m in length and 7 m in width in 1884 for the passage of a chain steamer, at the suggestion of the supervisory board of the cement works in Lauffen, chain shipping was extended to 12 km above Heilbronn. From a technical point of view, the conditions for this additional stretch were simpler than for individual sections of the river already used for chain shipping. Financially, the company hoped to generate additional income from the prospect of transporting limestone, coal and coke not only for the new route, but also on existing sections of the route. In contrast, the investment costs for operating resources were very low. The required chain length was still available in stock. The wear and tear of the chain links on their contact surfaces resulted in an elongation of the chain, which was slight per chain link but considerable over the entire length of the chain. Therefore, over the years, pieces of chain have been cut out and stored again and again. In addition, the chain was subject to increased stress and wear in river sections with very high currents and tight curves. Since at the same time a chain break in those river sections would have far greater consequences, the chain had to be replaced earlier. However, these chain sections were still usable for the new route with a smaller number of towed ships. Thus, the extension of the line to Lauffen paid off without a new state guarantee and was implemented in 1890 after the concession was extended.

In 1890, coal accounted for around two thirds of the cargo on mountain loads (including deliveries to Lauffen). About three quarters of the valley cargo consisted of salt transports, about half of which came from the Friedrichshall saltworks in Jagstfeld.

In the years 1892/93 the persistent drought of the Neckar shipping caused particular problems. In the first year shipping had to be partially stopped due to low water. Since the Rhine was not affected, the cargo was loaded directly onto the railroad in Mannheim. In 1893 the situation was much worse. Lack of rain and irrigation with river water caused the level of the Neckar to drop further. The low water level was also used for extensive clearance work and river construction, so that tug shipping could only use around 60% of the working days. This meant that the tug company had to make use of the state guarantee for the first time.

The Neckar shipping industry suffered a similar setback in 1895. A long, severe winter was followed by heavy flooding, so that towing operations could not begin until April. The dry summer in turn caused the towing operations to be temporarily suspended due to low water levels. In addition, the low water levels on the Rhine sometimes caused the supply of goods to stall. Tug shipping was again only able to use around 60% of the working days and had to make use of the state guarantee a second time. Over the years, however, these grants from the state of Württemberg were considerably lower than the profits that were paid to the state in other years.

During the time of chain shipping, the average cargo space of towed ships has increased significantly. In 1878 the maximum load-bearing capacity per ship was still 55 t on average , but this increased to around 100 t by 1892/93. The 130 t limit was exceeded around 1900. However, due to the narrow bends in the river and the strong seasonal fluctuations in the water flow of the Neckar, most of the ships remained below 200 t deadweight.

technical description

The engineer Ewald Bellingrath , who had been appointed advisor to the provisional committee up to that point, took over all technical matters . He worked out plans, procured the equipment and supervised the technical execution. He had Neckar boatmen trained on his chain ships on the Elbe.

The chain

The 115 km long drag chain consisted of 26 mm thick and 110 mm long, oval chain links and was tested for a breaking strength corresponding to 2.5 t. Two English plants supplied 70 km of chain, 35 km came from France and 7.5 km from a German plant. In addition, there were 2 km of used chain from the Elbe. The chain had a total weight of 1760 t and cost 592,000 Reichsmarks including laying. The laying began on March 23, 1878 in Heilbronn. The end of the chain was anchored above the railway bridge in the Neckar. The chain was exposed to constant wear due to friction and tensile stress.

The chain had a chain lock in the form of a shackle about every 500 m , with which the chain could be separated without destroying individual chain links. Depending on the flow conditions of the respective river section, the chain had to be replaced after 10 to 15 years.

During the towing operation, the chain pulls itself slightly towards the inside of the river bend in the area of strong river bends. However, the chain tractor moving down the valley can correct the position of the chain in the river bed.

The chain steamers

A general description of chain tow steamers can be found in the main article chain towing vessel .

The order for the construction of the first four chain steamers went to the Saxon Steamship and Engineering Company in Dresden for 69,800 Reichsmarks each. However, this only delivered boiler plant and machinery to the Neckar, while the Neckar shipyard in Neckarsulm manufactured the hull. The same applied to the identically constructed fifth chain steamer, which was completed in 1880. The Neckar shipyard was bought in 1879 by Schleppschifffahrt auf dem Neckar AG for maintenance work on its own operating materials. The sixth and seventh chain steamers (1884/85) were planned and built at the Neckarsulm shipyard. Both ships contained a boiler and machine system from the machine factory J. Wolf & Co in Heilbronn.

The chain steamers were largely designed based on the model of the chain steamers on the Elbe. The chain was pulled out of the water at the bow via movable booms, guided to the actual drive via numerous guide rollers and placed back in the water at the stern of the ship via another boom.

With a length of 42 to 45 m and a width of no more than 6.5 m, the hulls were significantly smaller than on the Elbe in order to better follow the narrow bends of the Neckar. The draft of only 47 cm was also adapted to the lower water levels of the Neckar. The hull was only partly made of iron. The ship's deck and the level floor of the ship were made of wood, as this was considered more stable in the event of an accident.

The chain steamer was divided into three parts by two watertight bulkheads inside, each of which was only accessible from above. In the middle part there were two steam boilers next to each other with the associated coal bunkers. The boilers supplied the horizontally arranged twin steam engine with steam. The steam engine with an output of 81 kW (110 hp ) was in turn connected via a gearbox to the chain winch above the deck, made up of two drums arranged one behind the other. The chain followed alternately half the circumference of one drum and half the circumference of the other drum. In total, the chain was wrapped around the winch six half times. The drums had a diameter of 1.3 m and were each equipped with four running grooves. Two different speeds could be set via the change gear. The speed uphill was 4.5–5 kilometers per hour and downhill 10–11 kilometers per hour.

The other two areas at the bow and stern of the ship contained the operating and recreation rooms for the crew. The crew of seven consisted of a captain, helmsman, machinist, two stokers and two boatmen. On deck was the covered steering position with two steering wheels from which the two large rudders at the two ends of the boat at the front and rear were operated. In contrast to chain steamers on other rivers, the boats from the Neckar could only move on the chain and had no additional drive, independent of the chain, such as screw, side wheels or water jet propulsion. While they were towing ships uphill, they corrected the position of the chain in the river bed during the descent without attachments.

If two chain ships met, a complicated evasive maneuver was necessary, whereby the chain steamer going downhill went out of the chain and allowed the chain steamer going uphill to pass. This maneuver meant a delay of at least 20 minutes for the towing formation going uphill, while the ship going downhill suffered a loss of time of around 45 minutes.

The end of chain shipping

Due to the shallow water depth and the tight curvature, the size of most ships was limited to a carrying capacity of around 200 t. Sustainable success through the use of larger ships with a load capacity of up to 600 t could only be achieved by channeling the river. The interested chambers of commerce and municipalities therefore founded the “Committee for the Boost of Neckar Shipping” in 1897. This not only planned the canalization, but also thought about a large shipping connection between the Rhine and the Danube, which should run over the rivers Neckar, Rems , Kocher and Brenz . The chain shipping concession, which was issued until 1911, was then only extended for another 10 years, but expanded to include additional provisions. The chain-towing company received compensation for the hindrances caused by the construction work and the locks. At the same time, they were given the right of sole towing operation on the completed barrages.

After the end of the First World War , the Reich Waterways Administration began expanding the Neckar for ships 80 m long, 10.35 m wide and 2.3 m deep, which corresponded to a load capacity of around 1200 t. With the progressive commissioning of the individual barrages , the flow speed decreased and the water depth increased. Both of these made the chain steamers unprofitable compared to other tugs. As a replacement for two chain steamers, "Schleppschifffahrt auf dem Neckar AG" initially used two screw steam tugs on the pent-up sections of the route from 1925 onwards. These pulled the barges not only uphill, but also downhill. In the course of the further expansion of the Neckar, three motor tugs followed by 1929. At the same time, the number of chain steamers was further reduced. With the completion of the Großwasserstraße on July 28, 1935, after a total of 57 years, the last chain steamers on the last stretch between Neckargerach and Kochendorf had come to an end.

Curiosities

A humorous historical documentary can be found with Mark Twain , the famous Neckar traveler: “It was a tug, and one of a very strange construction and appearance. I had often watched it from the hotel and wondered how it was being propelled, because apparently it had no screws or blades. Now it came along foamed, made a lot of noise of various kinds and now and then increased it by making a hoarse whistle. ” The transport of heavy loads and the loud whistling brought the chain steamers on the Neckar the nickname“ Neckaresel ”among the population " a.

Museums with exhibitions on chain shipping on the Neckar

The House of City History and the City Museums Heilbronn dedicate their exhibition to Heilbronn Historically! Development of a city on the river with various exhibits, including part of the original chain, the chain shipping on the Neckar.

The Technoseum (State Museum for Technology and Work in Mannheim) and the Heilbronn Municipal Museums have models of Neckar chain boats.

In the shipping museum of the "Schifferverein Germania Hassmersheim 1912 eV" there is an approximately 4.5 m long diorama depicting a chain towing association. This was originally in the shipping museum of the city of Heilbronn.

literature

- Willi Zimmermann : Heilbronn - the Neckar: the city's fateful river . Verlag Heilbronner Voice , Heilbronn 1985 (series on Heilbronn, 10), ISBN 3-921923-02-6 .

- Hanns Heiman: The Neckar shipping since the introduction of tug shipping . Schmitz & Bukofzer, Berlin 1905 ( full text online in browser, free of charge, 118 pages, various formats for download, 14 files at archive.org; - Dissertation University of Heidelberg 20, March 1906, 102 pages (also in: Heiman: Die Neckarschiffer, part 2, Winter, Heidelberg 1907, OCLC 674274956 )).

- Helmut Betz: Tug shipping on the Neckar . In: Navalis . No. 2 . Knoll Maritim-Verlag, Berlin 2005, ISSN 1613-3646 .

- Willi Zimmermann: About rope and chain shipping . In: Contributions to the Rhine customer . Rhein-Museum Koblenz, 1979, ISSN 0408-8611 .

- Helmut Betz: History from the current tape. V: The Neckar shipping from the tow barge to the large motor ship , Krüpfganz, Duisburg 1989, ISBN 3-924999-04-X

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d The chain towing on the Neckar . In: Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung. 1885, pp. 363-365 ( original scan online ).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Chapter 1: Towing on the Neckar, its introduction and development. In: Hanns Heiman: The Neckar shipping since the introduction of tug shipping. Inaugural dissertation to obtain a doctorate from the High Philosophical Faculty of the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität zu Heidelberg. Schmitz & Bukofzer: Berlin 1905, pp. 7–26.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Willi Zimmermann: About rope and chain shipping. In: Contributions to the Rhine customer. published by the Rhein-Museum e. V. Koblenz, Issue 31, 1979, ISSN 0408-8611 , pp. 3-26.

- ↑ a b c d e Max Harttung: The chain towing ship on the Neckar . In: Württemberg year books for statistics and regional studies. Stuttgart 1894, pp. 303-327.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Sigbert Zesewitz, Helmut Düntzsch, Theodor Grötschel: Kettenschiffahrt. VEB Verlag Technik, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-341-00282-0 , pp. 137-142.

- ↑ a b c d e f Chapter 2: Die Neckarschiffahrt 1871-1901, their traffic and tariff development , In: Hanns Heiman: The situation of the Neckarschiffer since the introduction of the Schleppschifffahrt , Carl Winter's Universitätsbuchhandlung, Heidelberg 1907, S. 20-56.

- ↑ Sigbert Zesewitz, Helmut Düntzsch, Theodor Grötschel: chain shipping. VEB Verlag Technik, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-341-00282-0 , p. 224.

- ↑ Jan Bürger: The Neckar: A literary journey. Verlag CH Beck oHG, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-64693-5 , p. 97 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Peter Wanner et al. a .: Heilbronn historically! Developing a city on the river. The exhibitions in the Otto Rettenmaier House / House of City History and in the Museum in the Deutschhof (= small series of publications from the City of Heilbronn Archives. 62). Stadtarchiv Heilbronn, Städtische Museen Heilbronn, Heilbronn 2013, ISBN 978-3-940646-11-8 (Further series: Museo. 26. Further ISBN 978-3-936921-16-8 ), pp. 84–91, 116.

- ↑ TECHNOSEUM - State Museum for Technology and Work Mannheim, Collection EVZ: 1989/1479 , accessed on January 4, 2014.

- ^ Website of the shipping museum of the "Schifferverein Germania Hassmersheim 1912 e. V. " , accessed on December 28, 2015.