Hat law

The hat law ( Turkish Şapka kanunu ) from 1925 is one of Ataturk's reform or revolutionary laws . The law defines hats as permitted headgear for the male population of Turkey and prohibits the wearing of oriental headgear. For some of the civil servants it will be compulsory to wear the new "national headgear". The event is also referred to as the hat revolution ( Şapka Devrimi ) or hat reform ( Şapka İnkılâbı ), which the article also deals with. De jure , the law is still in force.

aims

According to Klaus Kreiser, there is no country in the history of which the type of headgear has been so regulated by state intervention as the Turkish one. Taking into account the socio-historical significance of the headgear, it also becomes clear that the hat revolution must be viewed as a tried and tested means of cultural policy in Turkish history and less as an expression of arbitrary oriental despotism.

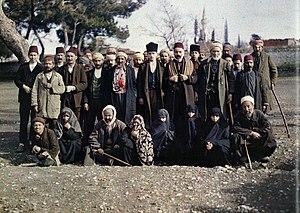

This clothing reform had several goals. Ottoman society split into wearers of various headgear. In the course of the emergence of the national idea, there was a lot of discussion among the Turkish upper class about the right choice of headgear as part of the “national costume”. With the hat law, the hat was enforced as "national headgear" and thus the previously prevailing heterogeneity, which allowed conclusions about denomination, political convictions and ethnicity, was dissolved in the sense of a single citizen. The aim was also to strengthen the reputation of the Turk at the international level and to make him part of the “civilized world”. At the same time, it was an optical break with time and as unaesthetic clothing of the fallen Ottoman Empire .

Another goal was the formation of a visible profession of the clergy ( Hodscha ). Only this profession was allowed to wear the turban. The newly established Diyanet religious authority gave the Hodjas state authority to hold worship services - an activity that was previously open to everyone. With these two reforms, it was now clear to the population based on the turban whether the imam carried out his profession with state permission and, secondly, the state could now determine whether the clergyman with his religious clothing could do further economic activities that were forbidden to him because of abuse of office, business.

Background: Kulturkampf over headgear

As the spiritual forerunner of the hat revolution, Mahmud II ordered the state compulsory festival in 1827. In the course of a western-oriented, compulsory redesign of the civil servants, the Fez was supposed to replace the then dominant turban at the state level and in the population and to conceal religious differences (visible through the headgear). This provoked angry protests from conservative sections of the population who criticized the ban on the turban as a betrayal of Islamic principles and popularly called the sultan "Gâvur Padişah" (infidel Sultan).

In the course of time the Fes developed into a patriotic symbol of the Ottomans , but lost its homogenizing effect with u. a. the advent of the hat, which rivaled it. This was often, but not exclusively, worn by urban non-Muslims as a status symbol and as a demarcation - in times of the increasing decline of the Ottoman Empire and interreligious conflicts, to the annoyance of many Muslim citizens. In his memoirs, Falih Rifki Atay says that the population divided the Giaurs into three categories, the level-headed unbelievers, the normal unbelievers and, as the worst category, the unbeliever with hat ( şapkalı gavur ) wear. In order to stop the hat from penetrating the Ottoman civil service, Abdülhamid II banned the hat in 1877 and urged that the fes be retained. Hat wearers had to expect dismissal and imprisonment.

The Fes received another blow from the Young Turks. Since the Fez - as the patriotic symbol of the Ottomans - was largely produced abroad towards the beginning of the 20th century, and especially in politically hostile Austria-Hungary (see: Bosnian annexation crisis ), it was increasingly hated and hated by the Young Turks boycotted. They now preferred to switch to the Kalpak , a Central Asian lambskin hat, and after they seized power made it mandatory for soldiers in khaki colors with the Elbise-i Askeriye Nizamnamesi from 1909 . The theory of a Byzantine , i.e. Christian-Occidental origin of the Fez also reinforced the aversion. In his hat speech, Mustafa Kemal was later to report the rejection of the hat by conservative circles on the grounds of the Occidental-Christian origin of the hat and the retention of what they consider to be "Ottoman-Muslim" (but actually originating from the Occident and also in the " Christian enemy territory ”) criticize Fez as stupidity.

With the unpopularity of the Fes described, the future of headgear was discussed in intellectual circles and among generals. The question was whether the Fez should be retained as the national headgear, replaced by the Kalpak, or the hat should be adopted. While conservative sections of the population regarded wearing hats (and the kalpak) as harām for a Muslim , there were hat advocates in publications by the Young Turks (including the İçtihat ). They argued that the hat, which had also gained a foothold internationally in Japan and China, would best correspond to a new Turkish national understanding as a modern piece of clothing. Even Mustafa Kemal was influenced by this discussion.

Bad experiences of my own and those of other Ottoman travelers in traditional costume in Europe may also have contributed to the decision. Mustafa Kemal's companion Selahettin Bey was harassed at the Belgrade train station because of his fez and children they met avoided her. Troop exercises in French Picardy , in which Mustafa Kemal participated in 1910, are said to have left a lasting negative impression. Mustafa Kemal is said to have contradicted his European colleagues as a military observer at the tactics discussions there, but was not taken seriously. When it became apparent in retrospect that Mustafa Kemal was right, a high-ranking European officer is said to have praised him and then pointed out that he would never be taken seriously with this head covering ( kalpak ).

Mustafa Kemal, for example, had announced his plans to establish the hat at a table talk in Erzurum in 1919 , which was met with great disbelief at the time. Six years later he was to realize this project as unreserved president.

Hat speech

Concrete steps to establish the hat were taken in 1925. For a test run, a trip to Kastamonu , a conservative and monarchist area, followed. In addition, he wore a summer hat ( panama hat ) for the first time , which he waved off his head in accordance with the etiquette as a greeting. In addition to the hat, this was also a novelty, as showing the bare head was still frowned upon in Ottoman society. In İnebolu he gave the so-called hat speech ( şapka nutku ).

“Are our clothes national? Are our clothes international? (No shouts) [...] Do you want a people without national clothing? Is that possible, friends? Are you ready to define yourself that way? (“No, definitely not” shouts) [...] Friends, there is no scope for exploring and reviving Turan's clothing . A civilized and international dress is essential for us. It is worthy clothing for our nation. Loafers or boots on your feet, trousers on your legs, waistcoat, shirt, tie, shirt collar, jacket and, of course, a headgear with a rim on your head. I would like to say this very frankly: this headgear is called a hat. Like a frock coat , a cutaway , a tuxedo or a tailcoat . Here is our hat. There are people who think it is not allowed to carry it. To them I would like to say: You are rather thoughtless and ignorant, and I would like to ask them: If it is a striving to wear the Greek-born fez, why should this not apply to the hat? [...] "

Legal background

The "Hat Wearing Law" was adopted by the Grand National Assembly of Turkey on November 25, 1925 and came into force as Law No. 671 when it was promulgated on November 28 of the same year. Art. 1 of

| Basic data | |

|---|---|

| Title: |

شابقه اکتساسی حقنده قانون Şapka İktisası Hakkında Kanun

|

| Short title: | Şapka Kanunu |

| Number: | 671 |

| Type: | law |

| Scope: | Republic of Turkey |

| Adoption date: | November 25, 1925 |

| Official Journal : | No. 230 BC November 28, 1925, p. 691 ( PDF file; 287 kB ) |

| Please note the note on the applicable legal version . | |

Law reads:

"

تورکیه بویوك ملت مجلسی اعضالری ایله اداره عمومیه و خصوصیه و محلیه یه و بالعموم مؤسساته منسوب مأمورین و مستخدمین, تورك ملتنك اکتسا ایتمش اولدیغی شابقه یی کیمك مجبوریتنده در. تورکیه خلقنك ده عمومی سرپوشی شابقه اولوب بوکا منافی بر اعتیادك دوامنی حکومت منع ایدر."

Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi aʿżāları ile idāre-ʾi ʿumūmīye ve ḫuṣūṣīye ve maḥallīyeye ve bi-ʾl-ʿumūm müʾessesāta mensūb meʾmūrīn ve müstaḫdemīn ė t Türkiye ḫalḳınıñ da ʿumūmī serpūşı şabḳa olub buña münāfī bir iʿtiyādıñ devāmını ḥükūmet menʿ ėder.

“Members of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey as well as officials and employees of general, special and local administration and all institutions are obliged to wear the hat worn by the Turkish nation. The general headgear of the people of Turkey is the hat and the government forbids the continuation of any contrary habit. "

Before the abolition of Art. 222 tStGB in March 2014, a short-term (cf. Art. 49 para. 2, 50 tStGB) prison sentence of two to six months was punished for those who violated the prohibitions or obligations set out in the Hat Act. The Hat Act is under the special protection of Art. 174 No. 2 of the Constitution ( Reform Protection Acts ) and Art. 22 No. 2 of the Constitutional Court Act.

consequences

As the Turkish press devoted a lot of space to the trip and the project, when Kemal Ataturk arrived in Ankara there were large crowds waiting for him in hats. Among them was Ali Bey, MP from Afyon, who shortly before had a journalist fired for wearing a hat and had charged him. Before the law was passed, there was a campaign in the newspapers to promote the hat, including a. Lessons how it was carried and how it was greeted. Even before the law was drafted, the hats were sold out in stores. Those who couldn't afford a hat improvised with fabric. Because of the demand, hats had to be imported from Hungary before local industry could develop. In Turkey, the hatmaker's profession ( şapkacı ) developed in front of which long lines formed.

The correspondence between the governors ( Vali ) and the Ministry of the Interior shows that the hat reform in the cities was almost completely implemented, but that some people viewed the hat with religious suspicion. They recommended that the Diyanet religious authority use fatwas to make it clear that wearing a hat was in accordance with Islam and not a sin. Because a point of contention that has always been discussed was the umbrella or hat brim . Since Muslims should touch the ground with their foreheads when praying, the new headgear turned out to be problematic in this regard, as people did not want to do without their headgear while praying. A fatwa made it clear that, contrary to popular opinion, bareheaded prayer is permitted and desirable from a religious point of view. As a compromise, the people on the brim loose attacked Takke or flat cap back.

In the rural population, this dress reform took place very slowly. This was due, on the one hand, to the low consumption of newspapers due to the low literacy rate and, on the other hand, to the limited control options in rural areas. There are reports, however, that when villagers went to the nearest town with the police there, they borrowed their hats from the community house and took them off when they returned.

The tour (including Mustafa Kemal) and parts of the public did not wear any headgear in later years. This was due to the new understanding of religion and life (the “desacralization of headgear”) and the parallel development of the dominant western fashion. While these developments and interventions with men took place on a legal level, at the time of Mustafa Kemal, contrary to some statements to the contrary in the literature, there were no legal unveiling or dress reforms with regard to women.

Reactions and protests

The police reacted differently to violators. Most of the time, the fez or turban was simply confiscated or the porter was brought to the police station. There have also been reports of physical assaults in the form of beatings by the gendarmes . The fine enshrined in the law was often applied because it proved to be a deterrent punishment, while the two to six month imprisonment sentence was imposed much less frequently.

The proportion of supporters and opponents in the population regarding the hat reform is difficult to determine. In general, the young men were more willing to wear the hat than the older men who had grown up with the Fez. A survey carried out in the Central Anatolian town of Kırşehir based on oral interviews with contemporary witnesses indicated a large majority for and opposition of only 15% (with 4% abstentions). Travel reports, however, testify to the greater unpopularity of the measure. However, Mustafa Kemal as the highest man in the state was held in high esteem in the population, which was still influenced by the Ottoman Empire, and the arbitrary police force and abuse that sometimes occurred was accordingly criticized at the local political level.

But there were also major protests critical of the regime. In Sivas , Rize , Trabzon , Maraş and Erzurum there were religiously motivated, sometimes violent riots that were severely suppressed. The protests were based on the one hand on the prohibition of the influential Islamic brotherhoods and on the other hand on the hat law, which the strict religious initiators of the uprising made use of. Since the political situation was tense due to a Kurdish uprising in the east, special courts (“ Independence Courts ” - İstiklal Mahkemeleri ) sentenced rioters arrested to prison and death sentences . The most famous convict is the radical Islamic scholar and opponent of the national movement İskilipli Atıf Hoca , who was classified as one of the organizers of the riot by the independence courts and hanged . A few years earlier he wrote a work in which he called the wearing of hats a sin and called on Muslims not to accept what he believed to be the bad influences of the West such as alcohol , prostitution , theater , dance and the wearing of non-Muslim headgear. Another execution victim was Şalcı Şöhret .

The law was passed almost unanimously in parliament . Two MPs, including Nureddin Pascha , described the reform as an unacceptable invasion of privacy and saw an incompatibility with dress codes that were already in place. He was referred by his colleagues to the existing hat obligation in the Japanese parliament and his argumentation was rejected as inconsistent because he himself wore a European cutaway .

Halide Edip Adıvar , a secular intellectual, was similarly critical of this . From her exile, she criticized that hat reform was too expensive for the poor and that the authoritarian invasion of privacy was too drastic. She feared that the expansion of westernization could be in danger.

Reactions abroad

The hat reform was persecuted abroad and especially in the Orient. While the western press was mostly astonished at this measure, sometimes mocked it and lamented the lost orientalist appearance of Turkey, similar measures were discussed in other Islamic countries.

There was a similar discussion in Egypt regarding Fez. There, too, the fez was viewed as a foreign cultural asset and complaints were made about the heterogeneity of the different headgear of the Egyptian population. While some Egyptian commentators advised Kemalist Turkey to better develop westernization in other areas, others saw hat reform as a suitable means of breaking with the Egyptian past (which for them was characterized by oriental ignorance and fatalism). Under Gamal Abdel Nasser , the fez should almost completely disappear.

The neighboring country of Iran followed suit a few years later. Impressed by the reform, Reza Shah Pahlavi ordered several clothing reforms with mandatory hats and hats for the first time in 1927 and later in 1935 after a state visit to Turkey. a. for the population and civil servants in Iran.

In the neighboring Syrian-French administered Hatay , parts of the local Turkish population began to wear hats and use Latin script to underline their sense of belonging. This led to reprisals and the violent confiscation of the hats by the French-Syrian side. The French called the hat-wearing insurgents chapiste ( Hütler ).

In neighboring Bulgaria, attempts were also made to get rid of the relic of Ottoman rule over Bulgaria, the Fez, and to introduce the hat instead. This measure should also be transferred to the Turkish minority, which resisted, in some cases violent, attacks. When asked how one connects this with the Turkish hat revolution in the mother country, the contemporary witness Osman Kılıç replied: “The idea of contradicting Ataturk's dress reform did not occur to us […]. But since we live in Bulgaria, in these terrible days [1930], far from the motherland, and since all our connections are severed and we have been left behind as orphans, our national clothing is the saving rock ”.

Others

The hat revolution is briefly covered in Saint-Exupéry's book The Little Prince . A Turkish scientist there warns of a comet with Fez, but is not given much attention. Only when he shows up wearing a tie and jacket is there applause.

literature

- Orhan Koloğlu: İslamda başlık, Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, 1978

- Hale Yilmaz: Becoming Turkish: Nationalist Reforms and Cultural Negotiations in Early Republican Turkey, 1923–1945, Syracuse Univ. Press, 2012, pp. 22-77

- Yasemin Doğaner: The Law on Headdress and Regulations on Dressing in the Turkish Modernization. (PDF file; 284 kB). In: Bilig 54 (2009), pp. 33–54 ( Hacettepe University , Institute for the History of Ataturk's Principles and Reforms).

Web links

- Ataturk's hat speech in Inebolu 1925 (Turkish)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Klaus Kreiser: Turban and Türban: 'Divider between belief and unbelief'. A political history of modern Turkish costume , European Review, Volume 13, Issue 03, July 2005, page 447, [1]

- ^ Bernard Lewis : The Middle East , 1995, Scribner [2]

- ↑ Hale Yılmaz: Becoming Turkish , Syracuse University Press, 2013, p. 41

- ↑ Necdet Aysal: Tanzimat'tan Cumhuriyet'e Giyim ve Kusamda Çagdaslasma Hareketleri. In: Çagdas Türkiye Tarihi Arastirmalari Dergisi. Volume 10, No. 22, 2011, pp. 3–32 (7) ( PDF file; 8.48 MB ).

- ↑ Fahri Sakal: Sapka Inkilâbinin Sosyal ve Ekonomik Yönü. Destekler ve Köstekler. In: Turkish Studies. International Periodical for the Languages, Literature and History of Turkish or Turkic. Volume 2, No. 4, 2007, pp. 1308-1318 (1312) ( PDF file; 465 kB ).

- ↑ Hale Yılmaz: Becoming Turkish , Syracuse University Press, 2013, p. 25

- ↑ Patrick Kinross: Ataturk. The Rebirth of a Nation. Phoenix (e-book), ISBN 978-1-7802-2444-2 , sp

- ↑ Klaus Kreiser: Ataturk. A biography. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-61978-6 , p. 145.

- ↑ Seçil Akgün: sapka Kanunu. In: Ankara Üniversitesi Dil ve Tarih-Coğrafya Fakuchteesi Tarih Bölümü Tarih Araştırmaları Dergisi. Volume 14, No. 25, 1981, pp. 69–79 (74) ( PDF file; 5.43 MB )

- ^ Klaus Kreiser: Small Turkey Lexicon . Munich 1992, p. 138.

- ↑ Fahri Sakal: Şapka İnkılâbının Sosyal ve Ekonomik Yönü. Destekler ve Köstekler. In: Turkish Studies. International Periodical for the Languages, Literature and History of Turkish or Turkic. Volume 2, No. 4, 2007, pp. 1308–1318 (1313) ( PDF file; 465 kB )

- ^ Bernard Lewis : The Middle East , 1995, Scribner [3]

- ↑ Hale Yılmaz: Becoming Turkish , Syracuse University Press, 2013, pp. 34–35

- ↑ Abdeslam Maghraoui: Liberalism Without Democracy: Nationhood and Citizenship in Egypt, 1922-1936, Duke University Press, 2006, p. 103

- ↑ Touraj Atabaki, Erik J. Zurcher: Men of Order: Authoritarian Modernization Under Ataturk and Reza Shah , IBTauris, 2004, p. 244

- ↑ Volkan Payasli HATAY'DA HARF İNKILÂBI'NIN KABULÜ VE YENİ ALFABENİN UYGULANMASI International Periodical For The Languages, Literature and History of Turkish or Turkic, Volume 6/1 Winter 2011, pp. 1697–1712, [4]

- ^ Mary Neuburger: The Orient Within: Muslim Minorities and the Negotiation of Nationhood in Modern Bulgaria , 2004, Cornell University, p. 96