Infanticide in the literature

Infanticide or infanticide was and is a frequent topic in the literature.

Childicide (infanticide) as the killing of (one's own) child can take place knowingly and due to lower motives (child murder) or unknowingly or through no fault of one's own (e.g. through accident, self-defense, state of war). One problem of a special kind is the neonaticide , i.e. the killing of newborn babies as a result of congenital disabilities.

In the history of literature there are the following types of infanticide: child sacrifice to a deity ( Isaac , Idomeneus ), unsuccessful infanticide ( Oedipus , Moses ), infanticide after adultery of the father ( Medea ), serial murder of children ( Herod ), killing of the son in a warlike manner Duel ( Hildebrand ), child murder after illegitimate birth ( Gretchen ), abortion .

The Sociobiology differs Infantizide in the animal kingdom, depending on the sex of the offender and pursued purposes.

The development of the infanticide motif in the history of literature shows a change that ranges from the matter of course of ancient child abuse to tragic father-son encounters to heretizing the child murderer. The turning point for the Christian development of the understanding of infanticide was reached through the Christian mission in Fulda. In modern times, the child murderer's social misery has been highlighted. Herein lies the merit of Goethe and his contemporaries. Finally, the indictment remains against a health policy that exposes poor people to horrific experiences during abortion (Brecht and Degenhard).

antiquity

In ancient Greece it was the right of every father to kill (e.g. abandon or sacrifice to a god) a child he did not want to accept.

Cunt

Moses is dumped into the Nile - albeit not with the intention of killing him - and saved by Pharaoh's daughter. She appoints a Hebrew wet nurse, Moses' birth mother, and takes the child as her own.

Abraham

The child as God's sacrifice is also known from the history of Abraham ( Genesis 22 EU ). Abraham received the commission from God to offer his only son Isaac as a human sacrifice. At the last second a ram appears and is accepted as a substitute victim. This shows the development of a new morality: God avoids infanticide.

Jephtha

In the Book of Judges 11: 29-37 EU it is told how Jephtha vows before a battle against the "children of Ammon" that he will offer as a human sacrifice those who will come to meet him first of all when he returns home. The daughter - the ruler's only child - turns out to be the one to be sacrificed. She asks for two more months to mourn her virginity with her friends. Then the horrific sacrifice is made.

The biblical myth was treated by Handel in his last oratorio.

Hesiod

In Hesiod's "Theogony", the Titan has Chronos killed his children because he was predicted that one of the children would kill him and take control. Zeus is the only one of the children to survive and fulfill the prophecy.

Lajos

Laius , king of Thebes had received the prophecy that a son whom he fathered with his wife Iokaste would kill him and marry his (Laius) wife. Shortly after Iokaste gives birth to Oedipus , Laios lets him - according to a late version of this legend - pierce his feet ('Oedipous' means "swollen foot" in Greek) and instructs a shepherd to abandon the child. By chance or because the shepherd took pity on the boy and handed him over, Oedipus reached the childless royal couple in Sicyon or Corinth , who raised him like a biological son. Now an adult he meets his (unknown) father at a fork in the road between Delphi and the Daulis , gets into an argument with him and kills him. Later he comes to Thebes, defeats the Sphinx and receives as a reward the kingship and the widowed Iokaste as wife, without knowing that Iokaste is his birth mother.

Medea

Jason steals the golden fleece from Colchis , and the daughter of King Aietes of Colchis Medea helps him. Jason and Medea become a couple and have two children. But when Jason wants to separate in order to marry the daughter of the Corinthian king, Medea presents her rival with a poisoned dress and kills both children. Thereupon she flees in the sun chariot of her grandfather Helios (sun god). Jason dies in old age under the rubble of his ship.

Idomeneus

According to ancient legend, Idomeneus , King of Crete, was caught in a storm on his return from Troy, which carried off all of his escort ships. He swears to the sea god Poseidon that he would sacrifice the first of his subjects to meet him at home in gratitude for his salvation. Landing in Crete, he first meets his son. However, human sacrifice is ultimately avoided when several members of the family offer to serve as human sacrifices in place of the king's son. Poseidon then lets everyone involved survive.

Herod

According to the Gospel of Matthew (Matt. 2, 16 ff), Herod had all children under the age of two killed because he had been prophesied that a child would be born who would take over rule. It shows the moral evaluation of Christianity: the murder of children is considered the most serious injustice. This new morality is offensive to ancient conceptions and only gradually gained acceptance on the European continent in the Christian Middle Ages.

middle Ages

Hildebrand

prehistory

From a Christian perspective, Charlemagne was a murderer and adulterer in his younger years. He was believed to have committed incest with his sister. Probably from this relationship the child was foisted on a vassal. He had deported several women for other marital relationships. He very likely had his brother Karlmann's children murdered. Roland's death is also likely caused by Karl's flight from the Basques. After all, he is responsible for genocide against thousands of Saxons.

On the other hand, the Fulda monastery owed Karl the so-called privileges. The monastery was considered to be entitled to collect 10% of the income from the people, because Karl is said to have ceded this right to the monastery (forged donation of privileges).

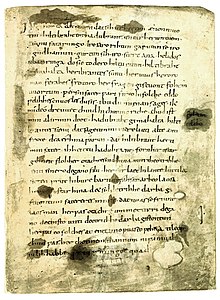

In this situation, the injustice had to be covered up. The war man (hilti = fight, brant = incensed) was upgraded as an innocently guilty war hero. It is unclear whether this dressing took place during the ruler's lifetime or not until the reign of Louis the Pious. However, maintaining the national language is closely related to the life's work of Rhabanus Maurus, who was abbot in the Fulda monastery from 820 to 840 (?). The only surviving manuscript of the Hildebrand's song is dated to this time .

action

Hiltibraht, a vassal of Dietrich von Bern, has been expelled from his kingdom of Verona ("Bern") and has joined the troops of Attila, king of the Huns. As a general of the Huns he comes to the gates of Verona, where Hadubrand - son of the lost Hilti wire - now rules. In order to avoid the countless killings of the warriors, a duel of the leaders should decide. Hiltibraht recognizes his own son and explains to him that he is about to fight his own father. Hatubrant (= inflamed for the sword) replies that he sees through the foreign warrior's intent to deceive. His father has been dead for years, he demands a duel. Innocently guilty, the father defeats the son and thus kills his own offspring.

interpretation

After it became clear that a model was used for the only surviving manuscript by two scribes from the Fulda monastery, the original of the Hildebrand's song has been puzzled over a lot. What is certain is that the only manuscript from which we know this wonderful Old High German song was notated on two book covers in a Latin script from the Fulda monastery. The scribes ignored important parts of the text and - for reasons of space - no longer wrote down the outcome of the fight between father and son (or in an unknown place).

As a decisive difference to the Greek antiquity it can be stated that now the father triumphs - not the son Oedipus as with Sophocles. The Carolingian epic glorifies the tragic child murderer in order to erect a memorial to Karl, the murderous ruler of the Christians. Child killing, which is unproblematic outside of Christianity, is presented as a major disaster ("wewurt skihit" = painful disaster occurs), which was groundbreaking for the Christian Middle Ages.

During the Christianization of the Frankish Empire, the great Karl was adorned with a myth that glorified his countless crimes.

Roland's song

Roland is the nephew (or illegitimate son) of Charlemagne. According to legend, Roland leads the rearguard when Karl is on his way back from Saragossa to Franconia. Allegedly intrigues have caused Roland to be ambushed and destroyed along with all of his men. He is said to have refrained from calling Karl for help so as not to lure the whole army into an ambush. Finally, Karl is said to have victoriously avenged the attack on Roland. Based on historical finds, Charles was by no means victorious. He was likely to have escaped across the Pyrenees with a narrow margin.

The French Roland's song treats Roland's tragic end in the first two (of five) parts.

The Regensburg priest Konrad translated the French Roland song into Middle High German around 1150. Here, too, the son sacrifice of Charlemagne is trimmed. The Carolingian self-evidence of the son-sacrifice is embellished as the heroic death of the faithful vassal. It is indirectly documented that the pagan self-evident nature of infanticide has been transformed.

The younger Hildebrand song

The Younger Hildebrand's Song is available in several versions from the 15th to 17th centuries and differs significantly from the older Hildebrand's song. It is written in early New High German, not like the older Hildebrand's song in Old High German. While the older Hildebrand's song was written in long Germanic rhyming verses, the newer Hildebrand's song is a poem in the form of final rhymes that follow the strophic form of the so-called Hildebrandstone . The decisive factor is the outcome of the conflict. In the more recent Hildebrandslied, too, the father Hildebrand triumphs over the son Hadubrand, but the son is not killed, rather both opponents are reconciled and the father is taken by the son to his wife Ute's table. The song closes with the conciliatory outcome of a reunion of the old couple.

Infanticide in modern literature

After the Christian morality of the sinfulness of killing one's own children had prevailed through tragic heroic stories, the issue of infanticide by women was a particular theme: witches who earned their living by abortion were persecuted by the inquisition; and young mothers who sought to hide the shame of their illegitimate conception by murder were immediately placed under secular jurisdiction.

In particular, the penal legislation of Charles the Fifth of Habsburg is cited as the source of a downright rabid legal conception. In 1516, Karl issued the Bamberg Embarrassing Neck Court Code with more severe sentences for mothers who had killed their children. They should not be "simply" executed; they should be buried alive, quartered with red-hot tongs, or staked. Later, public humiliation was added as a pre-execution ceremony.

The child murderer in the time of Sturm und Drang

Susanna Margaretha Brandt was tried in Frankfurt in 1771 for killing her newborn child and sentenced to death. Goethe attended this sad spectacle and had documents put together that he used to portray his Gretchen tragedy in "Urfaust". Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Heinrich Leopold Wagner , Strasbourg childhood friends in 1771/2, were unanimously of the opinion that child murderers were often innocent in serious internal and external conflicts. Therefore Wagner and the young Goethe dealt with this topic literarily.

Goethe

Goethe's Urfaust (1774) contains the Gretchen tragedy as a decisive novelty compared to the older Faust poems . Favored by the devil in the form of Mephistopheles, the young daughter of a poor widow is seduced. Mother and brother are killed by the work of the devil, and Gretchen murders the child that Faust conceived shortly after birth. After sentencing to death, Gretchen refuses Faust's offer of escape from the dungeon and renounces her lover.

The tragedy of the child murderer goes down in literary history as a trend-setting novelty. After the development of the concept of a capital crime (around 800 to the 1770s), the view of the tragic fate of the child murderer began to prevail. What, in the context of the Franconian Renaissance, with the tragedy of the killing of the son, had led to accusations of capital sin, which had lasted for centuries, is now relativized in the Gretchen tragedy.

wagner

Heinrich Leopold Wagner was a student friend of Goethe in Strasbourg. In 1776 he published his tragedy " The Child Murderer ". The young daughter Evchen accompanies mother and Mr. von Gröningseck to the theater and then to a dubious establishment. Von Gröningseck gave the mother a narcotic and raped Evchen. During a long business trip by the nobleman, Evchen receives a letter in which a friend of von Gröningseck pretends to be von Gröningseck. He assures her that he does not love her and that he does not intend to marry her. Evchen kills the child and is sentenced to death. Von Gröningseck finally confessed his love to Evchen and used himself in court for Evchen's pardon.

Schiller

In his poem The Child Murderer from 1782, Schiller describes the tragic end of a young woman who kills her illegitimate child because it reminds her of her birth father. The desperation of the young mother is presented from an almost psychiatric perspective.

Mozart

For the 25-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, “ Idomeneo ” (1781) is a case between father Leopold and son Wolfgang. Father Idomeneus is guilty by promising God a human sacrifice for his own survival. In fact, father Leopold had chased his two child prodigies across Europe, regardless of Wolfgang's delicate health. Eventually Wolfgang contracted endocarditis from which he died at the age of 32.

Old Hildebrand

The collection of German folk songs Achim von Arnims and Clemens von Brentanos ( Des Knaben Wunderhorn ) contains a song entitled "Der alten Hildebrand". It follows the version of the Younger Hildebrand's Song and adheres to the development of the subject, according to which infanticide is avoided: the father wins, but reconciliation and finally a re-encounter between wife Ute and old Hildebrand.

Hebbel's "Magdalena"

Friedrich Hebbel's drama Maria Magdalena depicts the child murderer in a modified - and in the present very topical - way. The daughter of an extremely respectful citizen drowns herself and her unborn child in a well because the biological father has renounced her for baser reasons and the father threatened to kill himself if the family were to be dishonorable.

Charles Gounod

In the Faust opera by the French romanticist Charles Gounod , Margarete is in the foreground. Margarethe's soprano aria, which is now known as the diamond aria, shows the main motif of Faust's lover: the jewelry that symbolizes the young girl's social advancement. The child murderer becomes a careerist in the struggle for a high social position.

Hauptmanns "Rose Bernd"

In his tragedy Rose Bernd , Gerhart Hauptmann portrays the child murderer as a victim of social conditions. Rose Bernd is engaged to August. However, she is impregnated by Christian Flamm. After numerous insults and fights, Rose murders her newborn child in a kind of mental confusion. As a justification, she states that she wanted to prevent her own child from going the same way as herself.

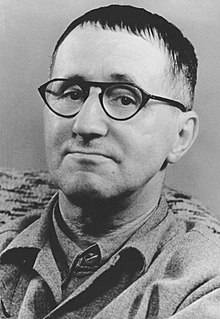

Bertolt Brecht

In the 20th century, the child murderer's perspective shifts to pregnancy.

"Marie Farrar born in April,

a child, featureless, rickets, Orphan

Until now supposedly blameless, wants

a child murdered in the way:

She says she had been in the second month

A woman in a basement House

Tries to abort it with two syringes

Allegedly painful, but it didn't come out.

But you, I beg yourselves, don't want to fall into anger.

Because all creatures need help from everyone.

Nevertheless, she says, it paid for

what was agreed upon , from now on,

also drank fuel, ground pepper in it

But she only

got rid of it .

Her body was visibly swollen, she was

also very painful, often washing dishes.

She herself, she says, was still growing at the time.

She prayed to Marie, hoped for a lot.

You too, I ask you, don't want to fall into anger

Because all creatures need help from everyone ....

Marie Farrar, born in April,

died in the prison in Meißen,

Unmarried mother of children , sentenced, wants

you the ailments of all creatures prove.

You who give birth well in clean puerperal beds

and call "blessed" your swollen wombs

do not want to condemn the rejected weak

For their sin was great, but their suffering was great.

Therefore you, I ask you, do not want to fall into anger

For all creatures need help from everyone. "

Degenhard

In his song about the story of the O, Franz Josef Degenhardt took the child murderer out of the criminal subject and placed it in the context of health-political indictments.

Moritat No. 218 (From the O and the P) Lyrics

“That is the story of the O

and the story of the P,

who are both from Hamburg.

Both had a child in their stomach.

On the left side of the river,

in Harburg, there lived the O,

on the right side the P,

and that's on the Elbchaussee. "

Schimmelpfennig

Roland Schimmelpfennig's opera of the year 2008 addresses the subject of Idomeneo : Father promises to sacrifice a person if the god of the sea saves his life.

literature

- Heinz Ludwig Arnold: Father Franz. Franz Josef Degenhardt and his political songs. Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek near Hamburg 1975.

- Hans Bankl: What they really died of. Vienna 1990.

- Pedro-Paul Bejarano-Alomia: Infanticide . Criminological, legal history and comparative law considerations after the abolition of § 217 StGB old version Berlin 2008. (At the same time dissertation Freie Universität Berlin 2009).

- Hartmut Broszinski: Hilabraht. The Hildebrand song. Facsimile of the Kassel manuscript with an introduction. Kassel 2004.

- J. De Vries: The motif of the father-son fight. In: K. Hauck (Ed.): On the Germanic-German heroic legend. 1961.

- Elisabeth Frenzel : Motifs of world literature. A lexicon of longitudinal sections of the history of poetry (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 301). 4th, revised and expanded edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-520-30104-0 .

- Johannes Fried: Charlemagne: violence and faith. Munich 2014.

- Charles Gounod: Margarete: from "Faust". Text book / libretto. [Paperback], Feldafing 1969.

- Luzie Haase: The ambivalence in the character of the figure Karl in "Roland's Song of Pfaffen Konrad": Analysis of the three dreams of the emperor. Düsseldorf 2013.

- Rebekka Habermas (ed.): The Frankfurter Gretchen. The trial of the child murderer Susanna Margaretha Brandt. CH Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-45464-X .

- Frank Häßler, Renate Schepker, Detlef Schläfke (eds.): Infant death and infanticide. MWV Medizinisch-Wissenschaftliche Verlags-Gesellschaft, Berlin 2008.

- Joachim Heinzle: Introduction to Middle High German Dietrichepik. (= de Gruyter study book ). Berlin 1999.

- Cornelia Houtman, Klaas Spronk: Jefta and his daughter. Reception history studies on Richter 11, 29-40. Lit, Berlin 2007.

- Hans-Wilhelm Klein: The chronicle of Charlemagne and Roland. Volume XIII, W. Fink-Verlag, approx. 1985.

- Kerstin Kloos: The representation of the mother characters in Gerhart Hauptmann's 'Rose Bernd'. Grin-Verlag, Augsburg 2005. (eBook, PDF)

- Christine Laudahn: Between post-drama and drama: Roland Schimmelpfennig's spatial designs. Narr, Tübingen 2012.

- Ludger Lütkehaus: The Myth of Medea. Texts from Euripides to Christa Wolf. Reclam, Leipzig 2007.

- Matthias Luserke: The child murderer and child murder as a literary and social topic. In: Reclam interpretations, dramas of the storm and stress. (= Reclam, Universal Library. No. 17602). Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-15-017602-6 , pp. 218-243.

- Hans Joachim Marx: Handel's oratorios, odes and serenatas. A compendium. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1998.

- Diana Raič: The killing of children by their own parents: sociobiographical, motivational and criminal aspects. Shaker Verlag, Aachen 1997, ISBN 3-8265-2707-0 . (At the same time: Bonn, Univ., Diss., 1995).

- Wolfgang Ranke: Maria Magdalena. Explanations and documents. Reclam, Ditzingen 2003, ISBN 3-15-016040-5 .

- Nikola Roßbach (Ed.): Myth Oedipus. Texts from Homer to Pasolini. Reclam Library, Leipzig 2005.

- Georg-Michael Schulz: Interpretations. Poems by Friedrich Schiller. ISBN 3-15-009473-9 , pp. 15-26.

- H. Tellenbach: The father image in the West. Volume II 1978

- Eckart Voland : The sociobiology. The evolution of cooperation and competition. Spectrum, Heidelberg 2009.

- K. Wais: The father-son motif in poetry. Part I and II 1880–1930

- Sylvia S. Zimmermann: Telegonos. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 12, Metzler, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-476-01470-3 , column 90.

Individual evidence

- ↑ See Bejarano-Alomia 2009

- ↑ See de Vries 1961

- ↑ Voland 2009

- ↑ See Hässler et al. 2008

- ↑ Exodus 2.1-10 EU

- ↑ See Houtman / Klaas2007

- ↑ cf. Marx1998

- ↑ cf. Frenzel 1992, p. 729.

- ↑ See Roßbach 2005

- ↑ See Lütkehaus 2007

- ^ Paul Weizsäcker: Idomeneus 1). In: Wilhelm Heinrich Roscher (Hrsg.): Detailed lexicon of Greek and Roman mythology. Volume 2.1, Leipzig 1894, Col. 106-108. The detailed narrative has been handed down by Pseudoappolodor cf. Appollodor: Libraries of Apollodor 3,3,1 Cf. also the sections on Mozart's opera and Schimmelpfennig.

- ↑ See Ernst Baltrusch: Herodes. King in the Holy Land. CH Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-63738-4

- ↑ See Klein 1985

- ↑ See Fried 2014

- ↑ See Broszinski 2004

- ↑ cf. De Boor 1964, pp. 65-71 ff.

- ↑ See Fried 2014

- ↑ Haase 2013

- ↑ See Heinzle 1999

- ↑ See Raick 1997

- ↑ See Habermas 1999

- ↑ See Habermaas 1999

- ↑ See Luserke 1997

- ^ Schiller, Friedrich: Complete poems I. Ed. Gerhard Fricke and Herbert G. Goeppert. Munich 1962, p. 43 ff.

- ↑ See Bankl 1990

- ↑ Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano: Des Knaben Wunderhorn. Volume 1, Stuttgart a. a. 1979, pp. 121-126.

- ↑ See Ranke 2003

- ↑ Cf. Gounod 1969

- ↑ See Kloos 2005

- ↑ Brecht 1922

- ↑ From the child murderer Marie Farrar. In: Bertolt Brecht, Libro di devozioni domestiche - in Poesie 1918-1933, traduzioni di Emilio Castellani e Roberto Fertonani, Torino, Einaudi, 1968, pp. 16-23.1

- ↑ cf. Arnold 1975, quotation cf. Karl Adamek (ed.): Songs of the labor movement . Frankfurt / M. 1986, p. 250

- ^ Roland Schimmelpfennig, Der goldene Drache, Eleven theater pieces by Roland Schimmelpfennig, Fischer paperback, 2009; See Laudahn 2012

- ↑ https://de.slideshare.net/bejalde/dr-iurpedro-bejarano-alomia-llm-neonaticide-doctoral-thesis-2536177