Lock (weapon technology)

The breech is an assembly of a breech loader and closes the barrel to the rear. The closure prevents propellant gases from escaping to the rear. It must be stable enough to withstand the pressure of these gases. In the case of weapons for cartridge ammunition , the cartridges are fixed in place by the lock in the barrel and the seal is achieved by loosening the case material.

As a locking system, the lock can take on other functions such as loading, firing, securing and unloading the weapon.

history

Already at the time of muzzle loading rifles , the need was recognized to get to the part of the barrel, which was tightly closed at that time and in which the powder was to be ignited, in order to fire the bullet placed in front of the powder from the barrel. If the powder didn't ignite, removing the bullet from the barrel was a cumbersome task. The solution to this problem was the forerunner of firearm breeches, the tail screw that closed the barrel to the rear, or the development of chamber guns with a detachable chamber for the charge.

An intermediate step in the development of modern locking systems formed the 1827 by Johann Nikolaus von Dreyse developed Zündnadelsystem whose development has to in the years 1839 to 1840 by the Prussian army tested breech-loading rifle led.

Another path was taken in Bavaria : there, muzzle-loading percussion rifles were converted into breech-loading rifles with percussion ignition. The “ Podewils-Lindner rifle M1858 / 67” was built in 1861 as a muzzle loader “M / 58 / II” by Auguste Francotte & Cie in Liège, converted into a breech loader in Amberg around 1867 and renamed “M / 58/67 II” . The closure consists of a screw lock with a cut thread and a dust cover, which was developed by Edward Lindner. The percussion ignition remained virtually unchanged.

The advantage of breech loading rifles was their higher rate of fire and the ability to load these weapons while lying down without having to give up cover. Before the introduction of metal cartridge cases, the lack of gas tightness of the catches at that time was a problem, see Chassepot rifle and Dreyse needle gun . The propellant charge could be increased by the metal cartridge cases, since the expansion of the cartridge case in the cartridge chamber caused by the gas pressure leads to a liner that closes the cartridge chamber gas-tight to the rear. With the introduction of low-smoke ammunition, the locking systems had to be improved. In the case of the cylinder locks mostly used in army rifles, the locking elements were attached to the front of the bolt head, which made it possible to lock the bolt directly in the barrel extension.

Locking technology

When firing, the breech must withstand the high forces exerted by the gas pressure of the propellant charge, on the one hand to ensure the function of the weapon and, on the other hand, to prevent the shooter from being endangered by escaping gases or detonation. When calculating the locking elements, the peak pressure generated during combustion must be used. At a peak pressure of 1000 bar and a fogged closure area of 1 cm², the effective force is 10,000 N (approx. 1 t). In modern weapons, sealing to the rear is primarily carried out by the liner of the cartridge case, with the front surface of the bolt head adapted to the case, the butt base, supporting the cartridge base to the rear. Closures of weapons with caseless ammunition are positively sealed.

With the exception of muzzle-loading weapons and revolvers , practically all types of firearms have a breechblock. The lock itself may consist of various individual parts and thus form a lock system. For example, the following parts can be found in locking systems:

- Firing pin, also separate striking piece

- Firing pin spring

- Extractor (extractor claw)

- Gas take-off (for bolt reliefs of automatic weapons)

- Safety (various firing pin safety devices and hammer safety devices)

With a few exceptions (e.g. gas-tight revolvers), revolvers do not require any locking mechanisms. The drum forms the magazine and also the chamber, which is separated from the barrel. The seal is made by the liner of the cartridge case, the rear support of the chamber and the cartridge contained therein is ensured by the frame of the revolver.

Locking technology

Reason for locking

A closure must maintain the seal or support of the cartridge while the shot is fired and must not open before the gas pressure has dropped to a harmless level. In the case of self-loading weapons, unlocked locks are also used, in which the opening of the lock is positively delayed by its mass. However, a lock allows the use of much more powerful ammunition.

Unlocked lock (for self-loaders with the so-called safety section)

The unlocked lock (also referred to as a mass lock or spring-loaded mass lock ) is based on the inertia of a lock that is held relatively solid. When the shot is fired, the breech is set in motion by the recoil, this backward motion being slow enough to ensure that the case is only fully pulled out of the chamber after the gas pressure has dropped sufficiently. In these systems, the force of the return spring has hardly any influence on the opening behavior immediately after the shot has been fired. In the field of handguns, the bolt mass and spring tension place tight limits on the performance of the ammunition used. From a certain performance class of the ammunition, the bolt has to be made relatively heavy (see Uzi or Sten Gun ), or a very strong closing spring has to be used (see “Le Francaise” and old “Astra” weapons), which is the weapon handling difficult. In the area of larger-caliber weapons, unlocked ground locks were used, for example, on the on-board weapons MK 108 and MG FF .

Locked lock (for self-loaders with the so-called parking section)

When the bolt is locked, massive locking elements ensure the connection between barrel and bolt when firing.

Examples:

- Combs on the barrel, corresponding grooves in the slide, Browning system , Colt 1911 , barrel tilts to unlock.

- Locking block at the end of the barrel, locking in the slide's ejection window, Glock pistols, SIG 220. Barrel tilts to unlock.

- Combs on the barrel, corresponding grooves in the slide, Steyr M1912 , Beretta 8000 , Beretta Px4 Storm , Boberg XR9-S , Obregon pistol (Mexico), barrel rotates to unlock.

- Warts on the locking cylinder, Mauser System 98 and many others

- Quarter-turn lock: a rotatable sleeve encloses the chamber and the lock. Locking combs are attached to the inside of the sleeve and engage the corresponding counterparts in the lock. MG 30 and descendants, Solothurn S18 / 100

- Rotating head lock , M16 and G36 , AK 47, multi-loading and self-loading guns

- Support flaps, Sauer 80, Mg 51 , Browning Automatic Rifle ,

- Ball mechanism, Heym SR 30

- Bolt, pistol Walther P38 or Beretta 92 F

- Knee joint, Maxim machine guns, Borchardt and Luger pistols, early Winchester rifles.

Delayed mass closure

A non-rigidly locked mass breech of an automatic weapon in which the bolt head delays the return when firing is called a delayed mass breech .

Examples:

- Roller lock, H&K G3 rifle , assault rifle 57

- Leverage, FAMAS (leverage)

- Power transmission through sliding element, Thompson submachine gun

- Knee joint, machine gun Schwarzlose

- Various locking and locking systems

Wedge lock of an artillery gun

Krupp 1879, cross wedge lock

Knee joint lock on early Winchester bolt -action rifles

Timed shutter control

In addition to the point in time, the sequence of locking and unlocking the lock must be controlled mechanically. There are a number of different constructive solutions for this. The vast majority of solutions are based on the fact that the slide and barrel initially move backwards together when firing and separate when a defined point (e.g. a latch or control cam) is reached, i.e. H. the lock is released. A special solution to this problem is the "bent knee joint lock " of the pistol family of 08 pistols by Georg Luger (also: parabolic pistol ). The barrel then stops while the slide continues its backward movement until the force of the recoil spring drives it forward again. The barrel and breech then move back into their rest position together, whereby the locking occurs.

The mechanism of the breech and locking systems is controlled during the shot either via the recoil energy on the breech block or by reversing the entire system (barrel with breech such as cannons) or by gas pressure through a mechanical transmission of the energy of the accomplished when firing in all directions acting gas pressure on the breech and locking system (see gas pressure charger ).

While both systems are used in self-loading rifles and the gas-pressure guns are more common among modern weapons, locked self-loading pistols function - with a few exceptions - as recoil chargers (recoil and recoil).

Locking systems

A distinction is generally made between unlocked and locked locking systems. Unlocked locking systems work positively and are mainly used for weapons in small caliber or with small caliber ammunition; the exception are submachine guns. Locked locking systems work positively and are essential in weapons for firing strong ammunition.

Kipplauf lock

With this type of closure, the barrel can be tilted around an axis of rotation and thus releases the cartridge chamber so that a cartridge can be inserted or removed. The breech is part of the system housing ( receiver ) and is by far the most common type of receiver used today on shotguns and combined weapons . Kippball locks have been designed for breech loaders since the 18th century. The break-barrel lock is one of the most commonly used designs in modern hunting rifles and weapons for sporty shotgun shooting. In the widespread Greener system - also known as the Greener lock - locking wedges grip into hooks below the rear end of the barrel and lock the lock. The Kersten lock and the double bolt lock are also known. The lock shown in the picture has an additional locking element attached to the upper end of the barrel. Locking and unlocking is done manually by the shooter using an operating lever; the cartridges are lifted slightly out of the chamber when the breech is opened by the extractor. On some models, empty cartridge cases are ejected using a spring-driven ejector.

Modern rifles with a drop barrel lock usually have one to four barrels. In the case of multi-barreled weapons, there are numerous designs with different barrel arrangements and combinations of calibers.

Drop barrel revolvers form the link between the revolver construction and the drop barrel lock.

Block closure

Flap closure

The flap lock is a very old variant of a lock for handguns. Corresponding individual pieces are known from the 16th or even 15th century .

Flap-lock weapons are often converted muzzle-loaders. The reason is the shortness of the locking system, which can easily be attached to the rear of the barrel next to the lock. With the flap lock that opens upwards, the hinge is at the front over the running end. The lock is blocked with a swiveling wedge attached to the back of the block. The firing pin stored in the breech block is pressed backwards by a spring, the firing is usually carried out by the original percussion lock attached to the weapon, the hammer strikes the firing pin. Typical examples of flap-lock weapons are the US Army's Springfield trapdoor rifles and the Swiss Milbank-Amsler rifles.

Drop block lock

With drop block lock, the lock block is inserted vertically in the lock housing. For loading, it is pulled down using a lever mechanism to release the cartridge chamber. See also Sharps Rifle . In the Martini system , the breech block is hinged at the rear and is tilted for loading by pulling down the trigger guard.

The Bergmann pistol, the Lahti-35 and the StrikeOne are bolted recoil loaders and use this type of breech.

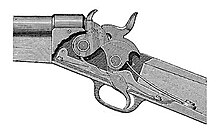

Rolling block closure

With the rotary block lock, the axle-mounted lock block is locked by the tap. For loading, the tap is cocked and the breech block tilted backwards. The cartridge is pushed into the open chamber. The locking block is then folded up; a spring prevents it from opening. When the trigger is pulled, the fast-moving cock locks the breech and ignites the cartridge.

Tilt block closure

The tilting block bolt, which is preferably used in gas pressure guns such as the Bren machine gun , the Tokarew-SWT-40 rifle and the MP 44 , is a modern further development of the block bolt.

Tabernacle closure

The tabernacle lock is structurally part of the block locks and is more precisely referred to as a shaft block lock with loading recess.

Cylinder lock

The cylinder lock is also referred to as a chamber lock . It is produced in various variants, but the locking principle is always the same. To unlock, the lock must be turned with the bolt handle before it can be opened. The locking takes place either via a different number of locking elements (cams or thread combs) that engage in corresponding recesses in the barrel or the system sleeve. In the case of small caliber weapons, it is often only done via the bolt handle, which engages in a corresponding recess on the side of the system case. The most widespread and copied is the Mauser lock ( Mauser System 98 , K98 ), which can still be considered the end point of a principle today.

The locking elements are not attached perpendicular to the axis of rotation, but slightly helical at an angle. The rotation when unlocking the lock consequently causes a return of 1 to 2 mm of the same, which loosens the sleeve via the extractor. This primary extraction significantly reduces the effort required to reload.

The straight pull fasteners are a variant . In these, the chamber or the locking sleeve belonging to the chamber is not rotated directly via the chamber stem, but via a loading lever which sets the chamber or locking sleeve in rotation via a correspondingly milled link. See also rotary head lock .

Knee joint closure

In the case of knee joint closure, the chamber (closure) is prevented from returning by an extended knee joint. In repeating mechanism ( Winchester (gun) ) for recharging the knee joint is bent by the operation of the loading lever, the shutter runs back the cartridge case pulls and pushes in the feed the new cartridge into the cartridge chamber .

In the case of self-loading and automatic weapons, the knee joint is overstretched before the shot is fired so that the bolt is securely locked. When the shot is fired, the recoil accelerates the barrel backwards together with the breech system. During the return movement, the knee joint is bent by a control curve, the slide continues to retract due to its inertia and the remaining pressure in the chamber, while the movement is stopped. In the return, the breech ejects the empty case. It is then accelerated forwards again by the recoil spring and inserts a new cartridge from the magazine or cartridge belt into the chamber.

The parabellum pistol is a locked recoil loader with this type of breech.

A special form of the knee joint lock can be found in the semi-automatic Pedersen rifle developed in America in 1923. In this case, the knee joint is not overstretched, but rather slightly bent, which means that it is opened with a delay due to the recoil. The system was not able to establish itself because a reliable function required greased cartridges.

Support flap closure

In the case of the support flap lock (also known as a swivel bolt lock), the backward movement of the lock is prevented by a bolt, which is supported on the lock housing when it is folded down. From 1881 the French company Darne in St. Etienne constructed not only conventional single shotguns but also those with a swivel bolt lock. For reloading, this was operated with a lever attached to the top. An early application found this locking system even when by Ferdinand Ritter von Mannlicher developed repeater system Mannlicher with straight-pull and the Ordonnanzgewehren Model 1885 and M1886 of the land forces of Austria-Hungary .

In the case of the gas pressure charger developed by John Moses Browning in 1918 , the Browning Automatic Rifle , the locking mechanism is prevented from returning by a swivel bolt.

The Mauser C96 , Walther P.38 / P1 and Beretta 92 are locked recoil loaders , in which the swivel bolt releases the connection between barrel and bolt after sliding back briefly on the so-called underlay section .

Special locking systems

Other locking systems can be found in particular on guns . While the locking systems described above are predominantly found in handguns, there are other technical solutions for locking design for guns, some of which are related to the locking systems above. These include, for example:

Locking systems of automatic weapons

The breeches of self-loading weapons are automatically opened after the shot has been fired in order to eject the fired case and cock the hammer. The closure may only be opened here when the gas pressure in the barrel has fallen to a sufficiently low value. This is the case shortly after the bullet emerges from the muzzle. Most self-loading weapons are calculated so that the inertia of the accelerated components is sufficient to tension the recoil spring so that it can complete the reload cycle. The "lock control" depending on the ammunition used is therefore a central structural problem for the construction of self-loaders.

Mass closure

The mass breech is an unlocked breech for automatic weapons, which ensures the breech function due to its own mass - in relation to the strength of the cartridge ammunition used with it. The mass of the breech is designed so that it allows a safe shot and the gas pressure acting backwards on the breech is sufficient for the repeating process (ejecting the fired cartridge case, cocking the hammer and trigger system as well as reloading the weapon with a new one Cartridge). The lock is controlled via the mass inertia of the lock. This system is used in automatic small bore rifles, self-loading pistols and submachine guns. The system is unsuitable for ammunition with non-cylindrical cases because of gas loss and case rupture.

Browning locking system

In the Browning system, the barrel and slide (slide) are connected to each other at the rear end of the barrel by means of two locking combs. After the shot has been released, both run back together; the running end connected to the handle via a chain link is pulled down through this. The connection between barrel and breech is thus released and the breech continues to freely run back. When the rear dead center is reached, the bolt is brought forward by the recoil spring for reloading and hits the barrel. This is brought up to its locked starting position by the chain link. The weapon is locked and ready to fire.

Roller lock

The roller lock is structurally a deflected mass lock and can be rigid (locked) or semi-rigid. With the semi-rigid lock type, lock designations such as “movably supported” or “delayed” are also used; these systems can also be referred to as “not rigidly locked”. These include the role of the closure Heckler & Koch - G3 - machine carabiner (as well as its derivatives including machine guns of the series H & K MP5 and the gun H K P S 9), and the assault rifle 57 the Swiss Army.

Gas-braked shutter

With gas-braked closures, part of the pressure in the barrel is diverted through bores to a piston surface, which counteracts the return of the closure. As a result, the mass of the breech can be kept smaller in contrast to weapons with a pure mass breech. In addition, a higher gas pressure in the barrel causes an increased pressure on the piston surface. This equalization of pressure means that the weapon works perfectly with different charges. Typical weapons with "gas-braked" breeches are the German Volkssturmgewehr VG 1–5 from 1945, the Steyr GB pistol , the HK P7 pistol series and the Walther CCP pistol .

Web links

- Locking systems at Waffeninfo.net

- Information on the forerunners of modern locking systems

- Shutters of the guns in Lueger: Lexicon of all technology (1904)

literature

- Lueger 1904 entry: hunting rifles

- Meyer's 1905 entry: hunting rifle

- Willi Barthold: Hunting weapon knowledge. 3rd edited edition. VEB Verlag Technik, Berlin 1979.

- Peter Dannecker: locking systems for firearms. 3rd revised and expanded edition. dwj-Verlag, Blaufelden 2009, ISBN 978-3-936632-20-0 .

- Vladimír Dolínek: Illustrated lexicon of small arms. K. Müller, Erlangen 1998, ISBN 3-86070-773-6 .

- Jaroslav Lugs: Handguns. Systematic overview of handguns and their history. 2 volumes. 8th edition. Military publishing house of the GDR, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-327-00032-8 .

- Craig Philip: Encyclopedia of Small Arms. Karl Müller, Erlangen 1995, ISBN 3-86070-499-0 .

- WHB Smith, Joseph E. Smith: Small Arms of the World. The basic manual of military small arms. American - British - Russian - German - Italian - Japanese, and all other important Nations. 5th edition, revised and enlarged, 3rd printing. Military Service Publishing Co., Harrisburg PA 1957.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Lueger 1904, entry: closure

- ^ Clifford Walton: History of the British Standing Army. Verlag Harrison and Sons, 1894, ISBN 9785879426748 (reprint), pp. 336–337 [1]

- ↑ Vivian Dering Majendie: On Military Breech-Loading Small Arms. March 1, 1867 in: Notices of the Proceedings at the Meetings of the Members of the Royal Institution. P. 69 [2]

- ↑ Graphic of a tilting block lock ( Memento from May 6, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Graphic mass closure ( Memento from May 27, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Graphic roller lock ( Memento from May 27, 2008 in the Internet Archive )