Piano Sonatas No. 19 to 21 (Schubert)

Franz Schubert's three piano sonatas nos. 19, 20 and 21 , German directory 958, 959 and 960, are the composer's last works. They were created in the last months of his life between spring and autumn 1828, but were not published until 1838–1839.

Like the rest of the composer's piano sonatas , they were viewed as "negligible" in the nineteenth century. In the late twentieth century, however, public opinion - and that of the critics - changed in this regard: Schubert's last sonatas are now counted among the composer's most important and most mature works, belong to the “hard core” of the piano repertoire and appear regularly on concert programs in recording media.

One of the main reasons for the long disregard of Schubert's piano sonatas is their disdain for the piano sonatas of Ludwig van Beethoven . This was still present and active for a large part of Schubert's short life. B. with his Diabelli Variations , with which he literally "crushed" contemporary competitors, including Schubert, so that Diabelli printed Beethoven's 33 variations on his theme in an extra volume (Volume I), while he listed the individual contributions of the other composers as " secondary ”(Volume II). Compared to Beethoven's 32 piano sonatas, Schubert's 21 piano sonatas were seen as clearly inferior not only in number, but also in structure and "content", although the three last Schubert piano sonatas contain specific allusions to Beethoven's compositions (see below) and although Schubert admired Beethoven very much.

Later musicological analyzes and comparisons have shown, however, that Schubert's last sonatas are unusually mature in their individual style and also convey this maturity in terms of content: They are now highly praised for this style, which is characterized by unusual cyclical form and sound properties, a specific chamber music texture and manifested in unusually rich expressions of emotion.

The three sonatas are cyclically linked with one another in various ways (see below), namely with regard to structural elements, elements of harmony and those of melody. These elements connect the different movements in each sonata, and also all three sonatas with each other. Consequently, they are often viewed as a “ trilogy ” that belongs together ; one could - alluding to the term cyclical - speak of a “ cycle of three piano sonatas”. The sonatas also contain specific allusions to (and similarities to ) other Schubert compositions, for example with his song cycle Winterreise (written in autumn 1827, i.e. less than a year before the piano sonata trilogy). These connections are based on the “ emotionally troubled” state - from a psychological point of view - in which the composer found himself at the time both the sonata trilogy and the Winterreise were composed. This "agitated state" favors - analogous to the eddy cycles in a turbulent flow - cycle formation and interdependencies of all kinds, but is often only dismissed as "very personal" and "autobiographical". Indeed: in various representations, the three sonatas were characterized using concrete psychological terms based on historical evidence from the composer's life.

History of origin

The last year of Schubert's life brought increasing public recognition for his compositional work, but also the gradual deterioration in his health. On March 26, 1828, Schubert gave a very successful concert with other musicians in Vienna with his own compositions, which brought him considerable income. In addition, two German publishers were interested in his work, which resulted in a short period of financial prosperity. But already in the summer Schubert was “short of money” again and had to give up some trips he had already planned.

Schubert was infected with syphilis by 1822 at the latest and suffered from weakness, headache, drowsiness and dizziness. But he had apparently led a fairly normal life until September 1828. During this month there were new symptoms of the disease, e.g. B. to bleeding. At this time he moved from Vienna, where he had lived with Franz von Schober , to his brother Ferdinand's house, which was more remote. Nevertheless, he composed with unbroken strength until the last weeks of his life in November 1828. Among other things, he wrote his last three piano sonatas.

Schubert probably began sketching the sonatas around the spring of 1828; the final version was created in September. During these months, the three Impromptus D 946, the E flat major Mass D 950, the string quintet D 956 and the songs that posthumously formed the so-called swan song were published . The last sonata, D 960, was completed on September 26th, and two days later Schubert played from the entire trilogy at an evening event in Vienna. In a letter dated October 2, 1828, Schubert offered the three sonatas to the publisher Probst for publication. But Probst was not interested in the sonatas, and Schubert died on November 19, 1828.

In the following year Schubert's brother Ferdinand sold the manuscript of the sonatas to the music publisher Anton Diabelli , who did not publish them until 1838 or 1839. Schubert wanted to dedicate the three sonatas to Johann Nepomuk Hummel , whom he had greatly admired. But when the sonatas were published in 1839, Hummel was dead, and Diabelli decided to dedicate the sonatas instead to the young Robert Schumann , who had on various occasions written very enthusiastically about Schubert.

Common structure

Schubert's three final sonatas share many structural features. Each sonata consists of four movements in the following order:

- The first movement always has a fast or moderately fast tempo and is laid out in sonata form . The exposure consists of two or three thematic and tonal units and performs as almost always in classical music from the root , the so-called. Tonic , the dominant (in Dur - keys ) or associated major tone at Moll -Tonarten (about from C to It in C minor). But, as is often the case with Schubert, the harmony scheme of the exposure involves additional passages with intermediate keys, which can be very far removed from the tonic-dominant relationship and sometimes literally “color” certain exposure passages with a transitional character. The main themes of the exposition are often in a triad relationship , with the middle section "evading" to a different key. The topics generally do not form symmetrical periods, and irregular phrase lengths are common. The exposure ends with a repeat sign. The development section begins with an abrupt transition to a new tone range.

- The second movement is always slow , sometimes “melancholy”, in the key complementary to the respective tonic and has A – B – A (ternary structure) or A – B – A – B – A form. The main sections (A and B) contrast in key and character, A is slow and meditative; B is louder and moving. The sentence starts and ends slowly and calmly.

- The subsequent scherzo or minuet is composed in the respective tonic, with the trio in a different key. A movement called Scherzo is in ternary form (ABA), with the B-flat section being composed in its own keys - keys that played a prominent or dramatic role in the preceding movements. The trio is in binary or ternary form.

- The final finale runs at a moderate or fast pace in sonata or rondo form. The themes of the movement are characterized by long melody passages with relentlessly flowing accompaniment tones in the bass. The exposure is not repeated this time. The developmental section here is kept in a simpler style than in the first movement, with frequent modulations , continuation sequences and fragmentations of the first theme of the exposition (or the main rondo theme). The repetition is very similar to the exposition, with the minimal changes in harmony necessary for the section to end in the tonic; the second theme is unchanged when it reappears, only transposed up a fourth. The coda is based on the first theme of the exposition. It is composed of two parts, the first of which is calm and restrained, creating an aura of expectation, while the second is agitated and "unloads" the final tension in decisive movement that finally ends in fortissimo chords on the tonic .

The sonatas in detail

Schubert's third from last sonata: Piano Sonata No. 19, C minor, D 958

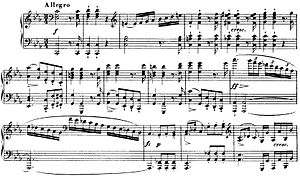

- Allegro.

- Adagio in A flat major, form: ABABA.

- Menuetto: Allegro Trio.

- Allegro.

Schubert's penultimate sonata: Piano Sonata No. 20, A major, D 959

- Allegro.

- Andantino in F sharp minor, form: ABA.

- Scherzo: Allegro vivace - Trio: Un poco più lento.

- Rondo. Allegretto - Presto.

Schubert's last sonata: Piano Sonata No. 21, B flat major, D 960

- Molto moderato.

- Andante sostenuto in C sharp minor, form: ABA.

- Scherzo: Allegro vivace con delicatezza - Trio.

- Allegro, ma non troppo - Presto.

Cyclisms

The above-mentioned cyclisms of the sonatas include, among other things, Krebsgang relationships. This means that a musical motif reappears in reverse, possibly after a very long time.

The cyclical structure of the three sonatas is particularly evident in an extreme example of the penultimate sonata, the A major sonata D 959: In the scherzo of the sonata, a cheerful passage in C major is suddenly interrupted by a wild downward movement in C sharp minor. In the third from last sonata there is an abrupt pause in the trio before the movement continues with a new section in a mysterious atmosphere.

Beethoven's influences

It is known that Schubert greatly admired the composer Ludwig van Beethoven . This is also manifested in Schubert's three last piano sonatas:

- The beginning of the third from last Sonata in C minor is almost identical to the theme of Beethoven's 1806 " 32 Variations on a Theme in C minor ".

- The structure of the finale of the penultimate sonata in A major is borrowed from the finale of Beethoven's piano sonata Op. 31, No. 1 .

But Schubert also deviated from Beethoven's role models in many examples, even when he was influenced by him. Perhaps the best example of this comes from the aforementioned finale of the A major sonata: although Schubert works with themes of the same duration, Schubert's sonata movement is much longer than Beethoven's. The additional length results from different episodes of the rondo structure.

A brief comparison of the three sonatas

Although the three sonatas form a cycle, as mentioned, they are of different characters: The first, D958, which begins with an eruptive series of violent chords, appears particularly “wild” and “stirring”, while the third, D960, is closed At the beginning it “flows evenly” and only gets a disturbing character in the further course. The character of the second of the three sonatas is rather “in between”.

Reception, criticism and continuation

Schubert's piano sonatas were viewed as “negligible” throughout the 19th century, often because they were judged to be “too long” or because they were denied “formal coherence” and “pianistic splendor” , etc. But two important composers of the Romantic period took the last three sonatas especially seriously: Schumann and Brahms .

- Robert Schumann, to whom the sonatas were dedicated (as reported above), gave a lecture in 1838 in his Neue Zeitschrift für Musik on the occasion of the publication of the sonatas. He expressed himself quite disappointed.

- Brahms' judgment deviated from this. He expressed the wish "to study the sonatas thoroughly" . Clara Schumann mentioned in her diary that Brahms had played the last sonata and praised his interpretation.

The negative attitude towards Schubert's piano sonatas lasted well into the 20th century. It was not until the hundredth anniversary of Schubert's death that serious attention was drawn to these works, and there were public performances by Artur Schnabel and Eduard Erdmann . During the decades that followed, Schubert's piano sonatas - and especially the last three - attracted growing attention. Towards the end of the 20th century they were seen as “really great works” , appeared regularly in concert programs of prominent pianists, were considered “equivalent” to Beethoven's late piano sonatas, etc. The B flat major sonata, D 960, the very last , has won the greatest approval and popularity among them.

Editions and Discography

Nowadays several sophisticated editions of Schubert's three last sonatas are available, namely those by Bärenreiter , Henle , Universal and Oxford University Press , some of which, however, have been criticized by prominent performers.

The works were interpreted and recorded by numerous pianists, some of whom recorded all three sonatas.

Joachim Kaiser has published interpretations of the last three Schubert piano sonatas in his Piano Kaiser collection - distributed on three different CDs - played by Alfred Brendel (D 958), Claudio Arrau (D 959) and Artur Schnabel (D 960) .

- The entire trilogy was recorded by: Leif Ove Andsnes , Claudio Arrau , Malcolm Bilson (on historical fortepiano ), Alfred Brendel (several recordings), Richard Goode , Wilhelm Kempff , Walter Klien , Stephen Kovacevich , Anton Kuerti, Paul Lewis , Radu Lupu , Alan Marks, Murray Perahia , Maurizio Pollini , András Schiff , Andreas Staier , Mitsuko Uchida .

- Sonata No. 19 in C minor (D 958): Sviatoslav Richter .

- Sonata No. 20 in A major (D 959): Vladimir Ashkenazy , Jorge Bolet , Christoph Eschenbach , Bruce Hungerford, Murray Perahia , Artur Schnabel , Rudolf Serkin , Krystian Zimerman .

- Sonata No. 21 in B flat major (D 960): Valeri Pawlowitsch Afanassjew , Géza Anda , Paul Badura-Skoda , Daniel Barenboim (2 recordings), Bruce Hungerford, Clifford Curzon , Jörg Demus , Leon Fleisher (2 recordings), Clara Haskil , Vladimir Horowitz (2 recordings), Maria João Pires , Menahem Pressler , Sviatoslav Richter (4 recordings), Arthur Rubinstein (2 recordings), Artur Schnabel , Rudolf Serkin (2 recordings), Dina Ugarskaja , Krystian Zimerman .

Audio files

Audio files for the piano sonata D 960 see right.

- Sonata in B flat major, D 960, interpreted by David H. Porter

- The same sonata performed by Randolph Hokanson

For audio files for the piano sonatas D 958 and D 959 see the chapters Editions and Discography and Web Links .

Further and referenced literature

- Badura-Skoda, Eva, “The Piano Works of Schubert”, in Nineteenth-Century Piano Music , ed. R. Larry Todd (Schirmer, 1990), 97–126.

- Badura-Skoda, Paul , “Schubert as Written and as Performed”, The Musical Times 104, no. 1450: 873-874 (1963).

- Brendel, Alfred , “Schubert's Last Sonatas”, in Music Sounded Out: Essays, Lectures, Interviews, Afterthoughts , au. Alfred Brendel (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1991), 72-141.

- Brendel, Alfred, “Schubert's Piano Sonatas, 1822-1828”, in Musical Thoughts and Afterthoughts , au. Alfred Brendel (Noonday, 1991).

- Brown, Clive, “Schubert's Tempo Conventions”, in Schubert Studies , ed. Brian Newbould (Ashgate, 1998).

- Brown, Maurice JE, “Drafting the Masterpiece”, in Essays on Schubert , ed. Maurice JE Brown (St. Martin's Press, 1966).

- Brown, Maurice JE, "Towards an Edition of the Pianoforte Sonatas", in Essays on Schubert , ed. Maurice JE Brown (St. Martin's Press, 1966), 197-216.

- Burnham, Scott, "Schubert and the Sound of Memory," The Musical Quarterly 84, no. 4: 655-663 (2000).

- Carlton, Stephen Edward, Schubert's Working Methods: An Autograph Study with Particular Reference to the Piano Sonatas (PhD diss., University of Pittsburgh, 1981).

- Chusid, Martin, “Cyclicism in Schubert's Piano Sonata in A major (D. 959)”, Piano Quarterly 104 (1978), 38-40.

- Cohn, Richard L., “As wonderful as Star Clusters: Instruments for Gazing at Tonality in Schubert”, 19th Century Music 22, no. 3: 213-232 (1999).

- Cone, Edward T., Musical Form and Musical Performance (New York: Norton), 52-54.

- Cone, Edward T., “Schubert's Beethoven”, The Musical Quarterly 56 (1970), 779-793.

- Cone, Edward T., “Schubert's Unfinished Business,” 19th-Century Music 7, No. 3: 222-232 (1984).

- Deutsch, Otto Erich , Franz Schubert's Letters and Other Writings (New York: Vienna House, 1974).

- Dürr, Walther, “Piano Music”, in Franz Schubert , ed. Walther Dürr and Arnold Feil, (Stuttgart: Philipp Reclam, 1991).

- Einstein, Alfred , Schubert: A Musical Portrait (New York: Oxford, 1951).

- Fisk, Charles, Returning Cycles: Contexts for the Interpretation of Schubert's Impromptus and Last Sonatas (Norton, 2001).

- Fisk, Charles, “Schubert Recollects Himself: the Piano Sonata in C minor, D. 958”, The Musical Quarterly 84, no. 4: 635-654 (2000).

- Fisk, Charles, “What Schubert's Last Sonata Might Hold,” in Music and Meaning , ed. Jenefer Robinson (1997), 179-200.

- Frisch, Walter, and Alfred Brendel, “'Schubert's Last Sonatas': An Exchange” , The New York Review of Books 36, no. 4 (1989). Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- Godel, Arthur, Schubert's Last Three Piano Sonatas: Genesis, Draft and Fair Copy, Work Analysis (Baden-Baden: Valentin Koerner, 1985).

- Gulke, Peter, Franz Schubert and his time (Laaber, 1991).

- Hanna, Albert Lyle, A Statistical Analysis of Some Style Elements in the Solo Piano Sonatas of Franz Schubert (PhD diss., Indiana University, 1965).

- Hatten, Robert S., “Schubert The Progressive: The Role of Resonance and Gesture in the Piano Sonata in A, D. 959”, Integral 7 (1993), 38-81.

- Hilmar, Ernst, Directory of Schubert manuscripts in the music collection of the Vienna City and State Library (Kassel, 1978), 98–100.

- Hinrichsen, Hans-Joachim, Investigations into the development of the sonta form in Franz Schubert's instrumental music (Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1994).

- Howat, Roy, “Architecture as Drama in Late Schubert”, in Schubert Studies , ed. Brian Newbould (Ashgate, 1998), 166–190.

- Howat, Roy, "Reading between the Lines of Tempo and Rhythm in the B-flat Sonata, D960," in Schubert the Progressive: History, Performance Practice, Analysis , ed. Brian Newbould (Ashgate), 117-137.

- Howat, Roy, “What Do We Perform?”, In The Practice of Performance , ed. John Rink (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

- Kerman, Joseph, “A Romantic Detail in Schubert's" Schwanengesang "”, The Musical Quarterly 48, No. 1: 36-49 (1962).

- Kinderman, William, “Schubert's Piano Music: Probing the Human Condition,” in The Cambridge Companion to Schubert , ed. Cristopher H. Gibbs (Cambridge University Press, 1997), 155-173.

- Kinderman, William, “Schubert's Tragic Perspective,” in Schubert: Critical and Analytical Studies , ed. Walter Frisch (University of Nebraska Press, 1986), 65-83.

- Kinderman, William, “Wandering Archetypes in Schubert's Instrumental Music,” 19th-Century Music 21, no. 2: 208-222 (1997).

- Költzsch, Hans, Franz Schubert in his piano sonatas (1927; rpt. Hildesheim, 1976).

- Kramer, Richard, “Posthumous Schubert”, 19th-Century Music 14, No. 1990, 2: 197-216.

- Krause, Andreas, Franz Schubert's piano sonatas: Form, genre, aesthetics (Basel, London, New York: Bärenreiter, 1992).

- Marston, Nicholas, "Schubert's Homecoming," Journal of the Royal Musical Association 125, no. 2: 248-270 (2000).

- McKay, Elizabeth Norman, Franz Schubert: A Biography (New York: Clarendon Press, 1997).

- Mies, Paul, “Franz Schubert's drafts for the last three piano sonatas from 1828”, Contributions to Musicology 2 (1960), 52–68.

- Misch, Ludwig, Beethoven Studies (Norman, 1953).

- Montgomery, David, Franz Schubert's Music in Performance: Compositional Ideals, Notational Intent, Historical Realities, Pedagogical Foundations (Pendragon, 2003).

- Montgomery, David, “Modern Schubert Interpretation in the Light of the Pedagogical Sources of his Day,” Early Music 25, no. 1 (1997): 100-118.

- Montgomery, David, et al. , “Exchanging Schubert for schillings”, Early Music 26, No. 3: 533-535 (1998).

- Newbould, Brian, Schubert: The Music and the Man (University of California Press, 1999).

- Newman, William S., “Freedom of Tempo in Schubert's Instrumental Music,” The Musical Quarterly 61, No. 1975, 4: 528-545.

- Pesic, Peter, “Schubert's dream”, 19th-Century Music 23, No. 2: 136-144 (1999).

- Reed, John, Schubert (London: Faber and Faber, 1978).

- Rosen, Charles , The Classical Style (New York, 1971), 456-458.

- Rosen, Charles, The Romantic Generation (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1995).

- Rosen, Charles, “Schubert and the Example of Mozart,” in Schubert the Progressive: History, Performance Practice, Analysis , ed. Brian Newbould (Ashgate), 1-20.

- Rosen, Charles, “Schubert's Inflections of Classical Form”, in The Cambridge Companion to Schubert , ed. Cristopher H. Gibbs (Cambridge University Press, 1998), 72-98.

- Rosen, Charles, Sonata Forms , revised edition (Norton, 1988).

- Schiff, András , “Schubert's Piano Sonatas: Thoughts about Interpretation and Performance”, in Schubert Studies , ed. Brian Newbould (Ashgate, 1998), 191–208.

- Schubert, Franz, Three large sonatas for the pianoforte, D958, D959 and D960 (early versions). Facsimile based on the autographs in the Vienna City and State Library, afterword by Ernst Hilmar (Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1987).

- Schumann, Robert , “Schubert's Grand Duo and Three Last Sonatas”, in Schumann on Music: A Selection from the Writings , ed. Henry Pleasants (Dover), 141–144.

- Shawe-Taylor, Desmond, et al. , “Schubert as Written and as Performed”, The Musical Times 104, no. 1447: 626-628 (1963).

- Solomon, Maynard, “Franz Schubert's 'My Dream'”, American Imago 38 (1981), 137-54.

- Tovey, Donald F. , “Tonality,” Music & Letters 9, No. 4: 341-363 (1928).

- Waldbauer, Ivan F., “Recurrent Harmonic Patterns in the First Movement of Schubert's Sonata in A major, D. 959”, 19th Century Music 12, No. 1: 64-73 (1988).

- Webster, James , “Schubert's Sonata Form and Brahms's First Maturity”, part I, 19th Century Music 2, no. 1: 18-35 (1978).

- Webster, James, “Schubert's Sonata Form and Brahms's First Maturity,” part II, 19th Century Music 3 (1979), 52-71.

- Whittall, Arnold, “The Sonata Crisis: Schubert in 1828”, The Music Review 30 (1969), 124-129.

- Winter, Robert, “Paper Studies and the Future of Schubert Research,” in Schubert Studies: Problems of Style and Chronology , ed. Eva Badura-Skoda and Peter Branscombe (Cambridge University Press, 1982).

- Wolff, Konrad, “Observations on the Scherzo of Schubert's B-flat major Sonata, op. Posth.”, Piano Quarterly 92 (1975-6), 28-29.

- Woodford, Peggy, Schubert (Omnibus Press, 1984).

- Yardeni, Irit, Major / Minor Relationships in Schubert's Late Piano Sonatas (1828) (PhD diss., Bar-Ilan University, 1996) (Hebrew).

Web links

- Piano Sonata D 958 , Piano Sonata D 959 , Piano Sonata D 960 : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Online audios of D958 (sentence 1) and D959 (sentence 1 to 4) can be freely selected here at PianoSociety

Individual evidence

- ^ Robert Winter, “Paper Studies and the Future of Schubert Research”, pp. 252-3; MJE Brown, "Drafting the Masterpiece," pp. 21-28; Richard Kramer, “Posthumous Schubert”; Alfred Brendel, “Schubert's Last Sonatas”, p. 78; MJE Brown, “Towards an Edition of the Pianoforte Sonatas,” p. 215.

- ^ András Schiff, “Schubert's Piano Sonatas”, p. 191; Eva Badura-Skoda , “The Piano Works of Schubert”, pp. 97-8.

- ^ Eva Badura-Skoda, "The Piano Works of Schubert", pp. 97-8, 130.

- ^ Schiff, “Schubert's Piano Sonatas”, p. 191.

- ^ Charles Fisk, Returning Cycles , p. 203; Edward T. Cone, “Schubert's Beethoven”; Charles Rosen, The Classical Style , pp. 456-8.

- ↑ Brendel, “Schubert's Last Sonatas”, pp. 133-5; Fisk, Returning Cycles , pp. 274-6.

- ↑ Martin Chusid, “Cyclicism in Schubert's Piano Sonata in A major”; Charles Rosen, Sonata forms , p. 394.

- ↑ Brendel, “Schubert's Last Sonatas”, pp. 99-127, 139-141; Fisk, Returning Cycles , p. 1.

- ↑ It is known that Schubert announced the “Winterreise” to his friends as follows: “Come to Schober tomorrow. I will play a circle of gruesome songs for you . ”(The word“ cycle ”stands for“ circle ”,“ cyclic ”means, among other things,“ in circular repetition ”.)

- ^ Fisk, Returning Cycles , pp. 50-53, 180-203; Fisk, “Schubert Recollects Himself”.

- ^ Fisk, Returning Cycles , pp. 203, 235-6, 267, 273-4; Fisk, “What Schubert's Last Sonata Might Hold”; Peter Pesic, “Schubert's Dream”.

- ↑ Elizabeth Norman McKay, Franz Schubert: A Biography , pp. 291-318; Peggy Woodford, Schubert , pp. 136-148.

- ↑ McKay, pp. 291-318; Peter Gilroy Bevan, “Adversity: Schubert's Illnesses and Their Background”, pp. 257-9; Woodford, pp. 136-148.

- ↑ Woodford, Schubert , pp. 144-5.

- ↑ MJE Brown, "Drafting the Masterpiece", p. 27

- ^ German, Franz Schubert's Letters and Other Writings , pp. 141-2.

- ↑ McKay, p. 307

- ↑ Kramer, “Posthumous Schubert”; Brendel, “Schubert's Last Sonatas”, p. 78; MJE Brown, “Towards an Edition of the Pianoforte Sonatas,” p. 215. The exact year of publication (1838 or 1839) varies depending on the source.

- ↑ See also the above-mentioned letter from Schubert to Probst, in German, Schubert's Letters , pp. 141-2.

- ↑ Irit Yardeni, Major / Minor Relationships in Schubert's Late Piano Sonatas (1828) .

- ^ Fisk, Returning Cycles , p.276.

- ^ William Kinderman, “Wandering Archetypes in Schubert's Instrumental Music”, pp. 219-222; Chusid, “Cyclicism”; Fisk, Returning Cycles , pp. 2, 204-236.

- ↑ Edward T. Cone, “Schubert's Beethoven”, p. 780; Fisk, Returning Cycles , p. 203.

- ^ Alfred Einstein, Schubert - A Musical Portrait , p. 288; Cone, “Schubert's Beethoven”, pp. 782-7; Charles Rosen, The Classical Style , pp. 456-8.

- ↑ Rosen, The Classical Style , pp. 456-8; Cone, “Schubert's Beethoven”.

- ^ András Schiff, “Schubert's Piano Sonatas”, p. 191. On the negative attitude towards Schubert's sonatas: see Arnold Whittall, “The Sonata Crisis: Schubert in 1828”; Ludwig Misch, Beethoven Studies , pp. 19-31.

- ↑ Robert Schumann, “Schubert's Grand Duo and Three Last Sonatas”; the translation cited here appears in Brendel, “Schubert's Last Sonatas”, p. 78.

- ^ Webster, "Schubert's Sonata Forms," part II, p. 57.

- ↑ Donald F. Tovey, "Tonality"; Eva Badura-Skoda, "The Piano Works of Schubert", p. 97; Schiff, “Schubert's Piano Sonatas”, p. 191.

- ^ Eva Badura-Skoda, "The Piano Works of Schubert", p. 98

- ↑ Brendel, “Schubert's Piano Sonatas, 1822–1828”, pp. 71-73; Schiff, “Schubert's Piano Sonatas”, pp. 195-6; Howat, “What Do We Perform?”, P. 16; Howat, "Reading between the Lines"; Montgomery, "Franz Schubert's Music in Performance".

- ↑ Perahia recorded the sonata twice - the first time individually, the second time with the other two sonatas.

- ↑ The recording was kindly made available by: http://www.musopen.com/