Winter trip

Winterreise op. 89, D 911 is a song cycle consisting of 24 songs for voice and piano that Franz Schubert composed in autumn 1827, a year before his death. The full title of the cycle is: Winterreise. A cycle of songs by Wilhelm Müller . Composed by Franz Schubert for a voice with accompaniment of the pianoforte. Op. 89. First section (songs I – XII). February 1827. Second Division (Song XIII – XXIV). October 1827.

Emergence

The texts come from Wilhelm Müller (1794–1827). He came from Dessau and frequented the Swabian circle of poets around Ludwig Uhland , Justinus Kerner , Wilhelm Hauff and Gustav Schwab . He was influenced by the romantics Novalis (Friedrich von Hardenberg), Clemens Brentano and Achim von Arnim . Franz Schubert was directly addressed by the poems and set them to music in the year of Wilhelm Müller's death, a year before his own death.

Schubert took the twelve poems from the "first division" of the Urania paperback for the year 1823 , where they were titled "Wanderlieder von Wilhelm Müller. The winter trip. In twelve songs ”appeared. Schubert kept the order and considered the cycle to be completed after the twelfth song; this is also shown by the “fine” at the end of the autograph of the first part. In 1823 Müller published ten more poems in the Deutsche Blätter für Poetry, Literature, Art and Theater and closed the cycle in 1824 in his work edition Seven and Seventy Poems from the papers left behind by a traveling French horn player. Second volume off - expanded to include Die Post and Deception and put in a new order.

The sequence of songs in Schubert's “First Department” is identical to that in Urania of 1823. He set the other twelve poems of the “Second Department” to music according to the order of the edition from 1824, omitting the songs he had already written. The only regrouping that Schubert carried out on his own initiative is the insertion of Die Nebensonnen between Mut and Der Leiermann . From Schubert's point of view, Müller's order is: Nos. 1–5, 13, 6–8, 14–21, 9–10, 23, 11–12, 22, 24.

According to the autograph , he set the first twelve poems to music in February 1827. Probably in the late summer of 1827, Schubert came across the other twelve poems, which he composed in October.

The Viennese publisher Tobias Haslinger published the songs in two volumes, the first on January 24, 1828, the second, six weeks after Schubert's death, on December 31, 1828 under the title: “Winterreise. From Wilhelm Müller. Set to music for a voice with accompaniment of the piano by Franz Schubert. 89th work "(publisher numbers 5101 to 5124).

Schubert and Müller did not meet personally, and whether Müller learned of Schubert's settings before his death in 1827 cannot be proven.

First performances: January 10, 1828, Musikverein, Vienna, by the tenor Ludwig Tietze (only No. 1); January 22nd, 1829, Musikverein, Vienna, by bassist Johann Karl Schoberlechner (No. 5 and 17).

content

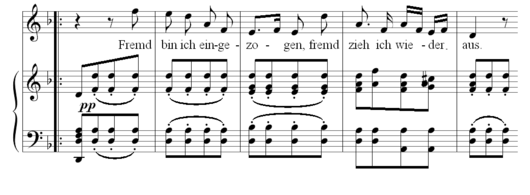

"Strange I have moved in, stranger I move out again" - with these verses the winter journey begins . It is one of the most famous song cycles of Romanticism, with which Schubert succeeded in depicting the existential pain of man. In the course of the cycle, the listener increasingly becomes the companion of the hiker, the central figure of the winter journey . After a love experience, he moves out of his own decision without aim or hope into the winter night. Müller's work can also be understood as political poetry in which he addresses his love of the country (i.e. the hope for freedom, liberalism and the nation state), which the princes have disappointed and betrayed .

No continuous storyline can be identified within the cycle. It is more about individual impressions of a young hiker. On the 24 stations of his passionate path, he is initially exposed to strong contrasts of mood, from exuberant joy to hopeless despair - made clear by Schubert through the frequent change of tone gender - before a uniform, but multifaceted, gloomy mood gradually asserts itself.

At the end of the cycle, the hiker meets the hurdy-gurdy man , who twists his lyre, freezing but not heard by anyone. The melody freezes here into a seemingly banal formula, the musical life has evaporated and the feeling seems to have escaped from an extinguished heart.

"Dreh'n Want to my songs your lyre?" With the question that ends Winterreise . Some see art as the last refuge in this song, on the other hand the hurdy-gurdy, which the traveler wants to join, is also interpreted as death. A third interpretation sees the “eternal lyre” as the expression of the agony of a hopeless but always lasting life.

Political interpretations of the winter trip

Through publications by various authors, a second level of interpretation of the winter journey has become public in recent years . With the setting to music of lines such as “Here and there some brightly colored leaves can be seen on the trees” (Song 16; Last Hope ), Schubert also deliberately and deliberately criticized the ruling system in a subtle way. For him, winter is also a metaphor for the system of reactionary restoration under Chancellor Metternich . Schubert, who maintained close contacts with opposition circles, was an important mouthpiece for intellectuals thanks to his exposed talent. The following song, Im Dorfe ("The dogs bark, the chains rattle, ..."), speaks for this interpretation. Schubert escaped a raid on his friends' dissident association in 1826 only with an early warning. The Leipzig literary magazine Urania with the texts of the poet Wilhelm Müller, which was banned in 1822 , was illegally obtained by Schubert. The astrophysicist and musician Andreas Goeres has published a detailed interpretation of the encrypted text passages. Reinhold Brinkmann put forward a different political interpretation : the Harvard musicologist sees the winter journey as an allegory of the “sacred art” that preserves the ideas of the revolutionary “time of power and action”. In contrast, Jürgen Hillesheim sees these political interpretations as often too superficial. He connects the cycle with pessimistic or fatalistic worldviews of the early 19th century, with the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer and the work of Georg Büchner . Based on Thomas Mann's artist novel Doctor Faustus , Hillesheim sees the Winterreise as the first “withdrawal” of the last movement of Ludwig van Beethoven's 9th Symphony .

Basic musical motifs of the cycle

The musicologist Harry Goldschmidt sees "the entire cycle held together by a few 'basic motifs'". After him, these three “basic motifs”, which can already be recognized in the two introductory bars, return from song to song in an ever-changing shape. Goldschmidt sees the first motif as the even eighth note with repetitions of notes or chords. B. is realized in the two opening bars in the left hand. The second motif is the sloping line or vocal line, as it is realized in the upper part of the right hand in bars 1–3 and in the singing line in bars 7 and 8. The third motif is the alternating note, which coincides with chord dissonances, as in the upper part of the right hand at the end of bar 2 and in bar 3 as well as in the vocal part in bar 9.

According to Goldschmidt, each “basic motif” has its own extra-musical meaning related to the text. The first motif stands with its "rigid regularity" for the "uniform walk through night and winter". The second motif with its falling vocal line represents the "languor" with which the "driven out" dragged himself through the wasteland. Goldschmidt describes the third motif rather vaguely as the “most secretive”, “motive of the motifs” and “the pain, the wound”.

In these cross-cycle motifs, Goldschmidt sees the “cyclical unity of related instrumental movements pursued by Beethoven with ultimate consistency”, which Schubert adopted primarily in his string quartets , also transferred to his lied work.

Elmar Budde also sees an “overarching cyclical context” that can no longer be reconciled with the “traditional concept of song” - as, for example, still followed in the beautiful miller's wife . However, in contrast to Goldschmidt, he sees the cross-song context more through “musical references due to the tonal proximity of the keys ” than through “motivic brackets”.

Songs

In the following, the titles of the songs are listed with their German directory numbers and a short analytical description.

Good night

1. Good night (“I moved in as a stranger”) D 911.1 in D minor

Text: The lyrical self takes leave of its previous abode and - above all - its loved ones. The love affair between the two was happy ( the girl spoke of love, the mother even of Eh ' ), but had to be ended - either because the lover turned to someone else or because her father forbade the relationship because of the difference in class (In " The weather vane ”learns the listener that it is the latter:“ What do you ask about my pain? Your child is a rich bride ”.). The lyrical self breaks out on a winter night and writes a good night greeting to the gate to his beloved, who is already asleep. The processing of this loss and, in general, of the alienation of the lyric self from its environment is the subject of the following cycle of poems.

Music: It is a varied verse song: the first two verses are musically identical, the third and fourth verses vary. The continuous eighth note accompaniment in the piano part characterizes the song as a typical song for the Winterreise , as it depicts the steps of the lyrical self that wanders aimlessly. The constant eighth notes (basic motif 1) also give the song heaviness, which is reinforced by the consistently falling melody of the vocal part in the minor parts (basic motif 2). With the word “die Liebe”, for the first time from bar 15, the falling line of the basic motif 2 in F major straightens up. The fourth stanza is in the major key of the same name in D major, since the lyrical self addresses its lover and longs for the past. In the last two bars of the fourth stanza, D major becomes D minor again. The final piano replay, in which the upper part falls from a '' to d 'and only the monotonous eighth note movement prevails, already indicates the hopelessness of the situation of the lyrical self.

The weather vane

2. The weather vane (“The wind plays with the weather vane”) D 911.2 in A minor

Text: The lyrical self takes offense at the weather vane that is written on the house of his beloved. It is interpreted as a symbol for the impermanence of love; the text also suggests that the love affair of the lyric self was broken off because the family home of the loved one chose a wealthier husband for her. The lyrical self sees itself sinking into insignificance ( What do you ask about my pain? Your child is a rich bride. ).

Music: The piano introduction in the second part of bar two and bar 3 refers to the first song with a variation of the sloping basic motif 2. and traces the gusts playing with the weather vane. The piano accompaniment consists largely of a melody that is played by both hands at octave intervals and is identical to the singing voice ( unison, colla parte ). The octave shift gives the song a gruesome character, which is reinforced by the fast tempo, trills, suggestions and arpeggiated chords. Here, too, when the rich bride is mentioned, the music modulates in the major key of the same name. The song ends without a chord on an a octave.

Frozen tears

3. Frozen tears (“Frozen drops fall”) D 911.3 in F minor

Text: The lyric self notices that tears fall frozen from his cheeks and wonders why they can freeze to ice, even though he cries out of ardent longing for his loved one. The lyrical self begins here - not for the last time on its journey - to doubt the intensity of its emotions and their source.

Music: The piano accompaniment is characterized by two rhythmic elements: once the syncopated half-note on the second beat in the left hand and once by the quarter-stressed right hand, which often has two eighths on the second beat. Due to the strong quarter orientation , one can speak of a song like in Gute Nacht . The song is also driven by the frequently occurring dominant on the fourth beat. The often staccated quarters symbolize the tears of the lyrical self. The sudden forte outbreak at the end (of the whole winter ice ) illustrates the agitated state of the lyrical self, which is still often discussed - especially musically.

solidification

4. Solidification (“I look in the snow in vain”) D 911.4 in C minor

Text: The lyrical self wanders through the snow, searches for the trail of its beloved and weeps for her. Nature is dead ( the flowers have died ) and in the search the motif from “Frozen Tears” is taken up, according to which the strength of his love is not enough to counter the ice and the freezing. So the only thing left for the lyrical self as a memory of its loved one is pain. The lines ( if my heart melts again, your picture flows too ) can be interpreted as a decision to include the picture of the beloved in the heart and never fall in love again.

Music: The accompaniment consists of very fast eighth note triplets and a recurring bass melody. This illustrates the emotionally driven, also hectic search of the lyrical self for traces of the past. When I cry out with my hot tears , the A- flat is found as one of the highest notes of the singing voice in Winterreise. The thought of the past becomes very clear in the middle section ( Where do I find a blossom? ), Which is in A flat major, but the memory is musically destroyed by persistent diminished chords.

The linden tree

5. The linden tree (“At the fountain in front of the gate”) D 911.5 in E major

Text: The lyrical self walks past a linden tree in front of the city gate, which it sees for the last time. (The linden tree is often used in romantic literature as a symbol of home and security.) The lyrical self feels strongly drawn to the tree and has to close its eyes as it walks past and force itself not to turn around, as the linden tree has a tremendous attraction to it affects. The verse You would find rest there can be interpreted as a longing for death, which the lyrical self here opposes.

Music: The song begins with a prelude, which is strongly reminiscent of the previous song (eighth note triplets and bass line) through the sixteenth note triplets and the movement in the upper part. The initially homophonic , subordinate accompaniment of the singing voice gives the song a folk character. The key of E major reflects the remoteness of the lyrical self that is trapped here in the past and can hardly escape it. The text passages that relate to the present are set to music in a minor key: the octave-shifted accompanying voices in the first passage ( I have to wander even today ) are reminiscent of the weather vane , the second passage ( the cold winds blew ) forms one with its many semitone shifts stark contrast to the rest of the song. The song ends in E major again.

Flood of water

6. “Wasserflut” (some tears from my eyes) D 911.6 in E minor

Text: The lyric I speaks to nature here. It tries to change them with its falling tears and through the melting snow that flows back into the village to establish vague contact with its loved one.

Music: The four-bar rhythm ostinato in the piano, which is almost always the same, is reminiscent of a funeral march due to the dots and the slow tempo. The forte, which breaks out spontaneously from the pianissimo again and again, highlights emotional outbursts in the lyrical self.

On the river

7. On the river (“The one you rushed so merrily”) D 911.7 in E minor

Text: The lyric self is on a frozen river. It carves the name of its loved one into the ice. Now it compares its heart with the brook: It is frozen over on the surface, but is completely agitated underneath ( whether it swells so rapidly under its bark? ). The wanderer has not yet forgotten love. His heart can be easily injured, just like the layer of ice on the river ( I dig into your ceiling with a sharp stone ).

Music: Despite staccato, the accompaniment at the beginning reminds you of Gute Nacht , it is again a song . At the same time, the faltering staccato symbolizes the frozen bark. It also represents the heartbeat of the wanderer. The subsurface swell is expressed by accompanying sixteenth notes , which become more and more frequent and faster as the piece progresses; in the end it's thirty-second. The memory of the beloved is - as always - kept in the major key of the same name. The fifth, last stanza is strongly emphasized by repeated repetition, as here, in contrast to the first two stanzas, the psychological state of the lyrical self is again dealt with : Under its bark it is very agitated and can be carried away again to loud exclamations ( whether it is also swells so rapidly? ).

review

8. Review (“It burns under both feet”) D 911.8 in G minor

Text: The lyrical self is fleeing from the city of its loved ones, where it has been chased out by crows. It remembers how it moved into town and received a warm welcome there. It longs to go back to the house of its loved ones.

Music: The song is one of the most hectic in the Winterreise, which is mainly caused by the continuous eighth notes, combined with the sixteenth note-ups in the piano, which run through the whole song; the song is again a Gehlied . At the same time, the contrast between the present and the past becomes very clear here, which in turn is made clear by the change to the variant key of G major. The singing voice has almost only eighth and sixteenth notes in the first stanza, which underlines his hectic pace and flight ( I don't want to catch my breath again until I can no longer see the towers ). In the second stanza - the memory of the past - the sixteenth pauses between the syncopations are filled. Together with the binding of the eighth notes in the left hand and the major key, the presence of the first stanza is contrasted. In the third verse, the song initially returns to the minor key, but ends in major, as the lyrical self wants to return and cannot get away from the past.

Will-o'-the-wisp

9. Irrlicht (“In the deepest rocky depths”) D 911.9 B minor

Text: The lyrical self is deceived by a will-o'-the-wisp and gets lost in the mountains. It compares the work of the will-o'-the-wisp with the confusion of its life and thinks about death ( every path leads to the goal ; every river will win the sea, every suffering also its grave ).

Music: The will-o'-the-wisp is illustrated by unsteady rhythms in the piano, whereby Schubert often puts the fast note values before the slow ones in the beat, which is perceived as irritating when listening. As in a flood of water , the many dots are reminiscent of a funeral march, which here seems appropriate given the mention of the grave.

Rest

10. Rest (“Now I only notice how tired I am”) D 911.10 in C minor

Text: The lyric self feels tired when it takes a break. But the emotional pain comes back all the more now that hiking is no longer a distraction.

Music: Despite the rest, it is again a song because of the always present eighth notes . Schubert orients himself here mainly on the second stanza (but my limbs don't rest, their wounds burn ). A certain feeling of rest is conveyed by the harmonics, which usually only change in rhythm. Again the singing voice expresses the emotional turmoil of the lyrical self with a loud exclamation ( stir with a hot stab! ).

Spring dream

11. Spring dream (“I dreamed of colorful flowers”) D 911.11 in A major

Text: The lyrical self is brutally torn from a beautiful spring dream and looks for the way back from reality to its dream ( you are probably laughing at the dreamer who saw flowers in winter? ). Back in the memory of the dream, the lyrical self recalls the closeness of its beloved. The lyrical self is unable to suppress the memory of the past and longs for spring back ( when do you green leaves on the window? When do I hold my love in my arms? ).

Music: The music here is divided into three levels: first the swaying six-eight measure, which embodies the beautiful dream; Then the brutal awakening, which is expressed with rapid tempo, changes in minor, staccato and deep, threatening sixteenth tremolo, and finally the longing for the dream, which is closer to reality due to the concrete two-quarter time and at the same time holding on to it due to the return to major illustrated by the dream and the past. These three parts are repeated in the second three text stanzas. The end of the song, however, refuses to return to the major; the persistence in the dark minor variant can be seen as an indication of the wanderer's hopelessness. The final question of the song ( when do I hold my sweetheart in my arms? ) Is answered negatively by the sound of the minor tonic.

lonliness

12. Loneliness ("Like a cloudy cloud") D 911.12 B minor

Text: The lyric self is compared to a single cloud in the clear sky. He is met by calm and happiness while hiking. These impressions make it feel even more miserable ( When the storms were still raging, I wasn't that miserable. ).

Music: This song is characterized by continuous eighth notes in the first part and is therefore first a song . The loneliness of the lyrical ego is illustrated by the many incomplete two-chords and the few notes that the accompaniment initially consists of. In the second part, the accompaniment is strongly based on the storms with tremolos and sixteenth triplets. The miserable mood of the lyrical self becomes clear with the low-set final chord. It is important that Schubert composed and published this song as the final song of the first part of the cycle, since the second part of the song cycle, i.e. songs 13 to 24, was only published after his death. At the end of the first cycle, this song destroys the hope that was built up in the previous song “Spring Dream”.

The post

13. Die Post (“A post horn sounds from the street”) D 911.13 in E flat major

Text: The lyric I hears a post horn and feels excited, without first knowing why. Then it occurs to him that the mail is coming from his beloved's city, his heart wants to turn back and go to her again.

Music: The continuously dotted rhythm is reminiscent of the pounding of horses in the stagecoach (Schubert used the same method in his setting of Goethe's Erlkönig ).

The old head

14. The aged head (“The hoop has a white glow”) D 911.14 in C minor

Text: The hoarfrost on the head gives the lyrical self the illusion of white hair; but it soon melts, so that the illusion disappears. The lyrical self complains that it is aging so slowly and wishes for death. At the same time, it is afraid of the future, because the time that is still to be lived is felt to be unbearably long. The lyrical self is at the lowest point of its depression on its journey so far.

Music: The piano has a clear accompanying role; it accompanies the singer with long chords and only takes over the melody in interludes. In places the song is very recitative. At the words, how far from the grave! the accompaniment emerges clearly as the piano plays a movement offset by an octave that underlines the text eerily. The calm and indolence that dominates the whole song reflect the death wish of the lyric self.

The crow

15. The crow (“A crow was with me”) D 911.15 in C minor

Text: A crow has followed the lyric self since it left town. The lyrical ego thinks she would see it as prey, tells her that his life will soon end, and demands loyalty to the grave , which is probably a cynical allusion to the phrase until death is part of you . The crow is almost addressed as a friend and at the same time is a symbol of death.

Music: The piano accompaniment is set very high and symbolizes the flight of the crow with the high sixteenth triplets. The four-bar main motif of the song recurs again and again and probably symbolizes the circling of the crow around the head of the lyrical self. The word grave makes a strong exclamation , as it again illustrates the lyrical self's longing for death.

Last hope

16. Last hope (“Here and there is on the trees”) D 911.16 in E flat major

Text: The lyrical self plays a mind game: It hangs its hope on the leaf of a tree, sees it tremble in the wind and finally fall off. It sees all hope dead and weeping buries it in thought.

Music: The singing voice of this song has no melodic weight, the melody and accompaniment together form the harmony. Therefore, the harmony is difficult to grasp in many places. The tonic in E flat major is only reached in bar 8. This reflects the remoteness of the lyric self. The trembling of the leaf is indicated by a tremolo, the falling by a falling movement in the bass. At the words cry on my hope grave , the song suddenly becomes harmonious and homophonic. The death of hope is expressed with this church music character.

In the village

17. In the village ("The dogs bark, the chains rattle") D 911.17 D major

Text: The lyrical self walks through a village at night and is followed by growling and barking chain dogs. It sees people dreaming in their minds about things they don't have. People's dreams are seen as hope, but the lyrical self is at the end of all dreams, so it has no more hope.

Music: The half-bar accompaniment of eighth chords and sixteenth tremolos depicts - very lifelike - the growling and barking dogs. The middle section, in which the dreamers are talked about, has an accompaniment that hugs the singing voice more, but the monotonous one always follows repeating d in the upper part gives the part a bitter aftertaste. The two-bar homophonic outburst at the end ( what do I want to seam under the sleepers? ) Is strongly reminiscent of the end of the previous song: After hope, the lyrical self now also gives up its dreams.

The stormy morning

18. The stormy morning (“How did the storm tear apart”) D 911.18 in D minor

Text: The lyrical self looks at a morning sky that has been defaced by the storm: the clouds are torn and the sun is shining red behind them. It compares the sky with the image of its heart ( winter cold and wild! ), A reflection similar to that in On the River .

Music: The fast tempo, the continuous forte and the change between tied and staccato tones represent the storm. The song is composed in a similar way to Die Wetterfahne : the piano plays the melody in the vocal part with an octave parallel and creates a gruesome atmosphere. At less than a minute, the song is the shortest of the winter trip.

illusion

19. Deception (“A light dances kindly before me”) D 911.19 A major

Text: The lyric self follows a light on its journey, although it knows that the hope for warmth and security that the light radiates is only an illusion. The lyric self uses this deception to distract itself from its misery. The content of the text is somewhat similar to will- o'-the-wisps .

Music: In the accompaniment, the continuous octaves in the right hand are noticeable, which are accompanied by chords by the left hand. Together with the many tone repetitions in the accompaniment, a supposedly happy song emerges, which very strongly brings out the character of deception. For the beginning of no. 19, Schubert used T. 60–68 of no. 11.

The Guide

20. The signpost (“What am I avoiding the paths?”) D 911.20 in G minor

Text: The lyrical ego talks to itself about the fact that it wanders hidden paths in order not to meet any other person. It wonders why it seeks solitude, for it does not seem to fully understand its “foolish desire” itself. In addition to the many signposts on the paths, it sees someone who leads it to its death. In a figurative sense, he is shown the way to his grave. ( I see a sage standing steadfast in front of my gaze; I have to walk a street that no one has ever walked back. ) Here again the lyrical self's longing for death is strongly reflected.

Music: The song is characterized by the many tone repetitions both in the accompaniment and in the singing. The continuous eighth notes again show the character of a song . In a short major part, the innocence of the lyric self is emphasized. The slow tempo and the tone repetitions symbolize the death that the lyrical self yearns for. (Schubert uses this expression for death in a similar way in his art song Der Tod und das Mädchen .) In the second half of the song Schubert uses a sequence model that is tellingly called “Teufelsmühle” (cf. Voglerscher Tonkreis ) and with which it is always new surprising keys can be achieved. Schubert expresses that the hiker is disoriented and the signpost (s) do not help him either. The reference to the first part of the cycle is closely linked; a reference to the song “Rückblick” can be recognized, among other things, through the basic key of G minor.

- construction

Part A to measure 21, part B measure 22–39, part A 'measure 41–55, part A' 'measure 56 to the end

The tavern

21. Das Wirtshaus (“Auf einer Todtenacker”) D 911.21 in F major

Text: The lyrical self wanders through a cemetery and sees in it an inn that it would like to stop off at. But since no grave is open, it feels rejected ( are all the chambers in this house occupied? ). The lyrical ego feels fatally injured, by which the state of its soul is meant. Eventually it moves on.

Music: The major, together with the extremely slow tempo of a funeral march, represents the lure of death (similar to Der Lindenbaum ). The homophonically composed song creates a devotional mood to evoke the idea of the cemetery. The frequently occurring minor represents the pain the lyrical self experiences from being rejected.

Courage

22. Courage ("If the snow flies in my face") D 911.22 in G minor

Text: The lyrical ego wants to suppress the pain of its soul through happiness and suppresses it. In order not to feel the pain, it has to be exaggerated: If no god wants to be on earth, we are gods ourselves! The attempt at suppression is a sign that the lyrical ego cannot cope with its emotional pain and ultimately has to perish.

Music: The song starts out very eventful and interesting because the rhythm varies a lot. The constant change between the sexes makes this song very exciting. The forte in this song shows the true feeling and feeling of the lyrical self.

The suns

23. The minor suns (“I saw three suns in the sky”) D 911.23 A major

Text: Based on an optical phenomenon of secondary suns - to which the title of the poem clearly refers - the lyrical self tells of three suns that it has seen in the sky, but which were not its own. It says that it once had three suns itself, but the best two of them set. Now it wishes that the third would also perish. This third sun symbolizes the life of the lyric self (or its love), the other two were interpreted as faith and hope; the lyrical I lost the first two of the Christian virtues on his journey and now wishes to lose the love that torments him too. According to another interpretation, which is confirmed by the use of this image in other texts by Müller, the "best two" suns refer to the eyes of his loved ones. The secondary suns observed are not his, as they look into the face of others , so the protagonist sees his life devalued. The American musicologist Susan Youens points out that Müller replaces the classic poetic metaphor of the eye-stars, which symbolize eternity, with ancillary suns, i.e. a temporary optical illusion. In this way - similar to the symbol of the weather vane - the deceptive element of the love experience of the lyrical self is emphasized.

Music: Again it is a homophonic sentence. The piano accompaniment is set very low and repeats a saraband rhythm in the A sections , giving the sun phenomena a grandeur. What is striking is the low ambitus of the singing voice (minor sixth), which mainly moves in second steps throughout the song. The repetitive rhythm results in a static, non-propelling character, which illustrates the hopelessness, hopelessness and longing for death of the lyric self.

Symbolism: In the “minor suns” there is symbolism that refers to the number three. The three-quarter time, the three sharps in the basic key of A major, the form A – B – A and thus the melody that appears three times embody and run through the entire piece.

The lyre man

24. The Leiermann (“Over behind the village”) D 911.24 in A minor

Text: An old hurdy-gurdy staggered barefoot on the ice behind the village. Nobody pays him any attention, his music meets with absolute disinterest; only the dogs growl at him. Nevertheless, he continues to twirl his lyre, and the lyrical self wonders if it should go with him and sing to his hurdy-gurdy . The simple as well as poignant picture of the hurdy-gurdy spinning hurdy-gurdy, but still not making headway, fits well with the state of mind of the lyrical self as it has developed in the course of its journey. Susan Youens goes so far as to interpret the lyre man as a kind of doppelganger motif, which is more a projection of the wanderer than a physical existence. With the question Wonderful age, should I go with you? no hope is awakened that the life of the lyrical self will change for the better. Rather, it seals the incurable state of hopelessness and thus closes the cycle of poems.

Music: Schubert orients himself strongly on the image of the recurring lyre music (the hurdy-gurdy, a stringed instrument that has been struck off the wheel, not the organ grinder): The accompaniment consists of an always present, constant fifth of a and e in the bass, which is placed on the drone strings of the lyre alludes to; A short, recurring lyre melody sounds above it. The song is monotonous and very static due to its inertia and repetition, which corresponds very well to the lyrics. There are hardly any changes dynamically either, only in the last verse ( want to turn your lyre for my songs? ) A forte sounds like a final rebellion out of the monotony and hopelessness of the lyrical self. Only the music answers - in a very sophisticated way in bar 51 - the question of whether the lyrical self actually goes with death: exactly at the word "go" (... should I go with you?) The accompanying sixteenth-note figure begins for the only time in the whole Piece synchronized with the text - a sublime hint that corresponds to Schubert's subtle compositional style. The original version of this song was in B minor , but the publisher transposed it to A minor . Schubert made a suggestion for the constant fifth in the bass in the first two bars , which is missing in all subsequent bars. Individual pianists such as Ulrich Eisenlohr , Wolfram Rieger and Paul Lewis have recently played this suggestion at the same time as the bass fifth as a second chord and repeat this through all bars, so that there are constantly recurring dissonances right into the final bar. This way of playing, which deviates from the musical text, is sharply criticized by Schubert researcher Michael Lorenz . Even Franz Liszt added these suggestions into its transcription for solo piano.

reception

The cycle has been interpreted by almost all major song singers (bass, baritone, tenor), but also by female singers (mezzo-soprano, alto, soprano). In addition to the cycle “ Die Schöne Müllerin ”, the work is considered the highlight of the song cycle genre and the art song . It is a great challenge for singers and pianists, both technically and interpretatively. Over 50 different recordings exist on records and CDs.

The German composer Hans Zender arranged the work under the title: "Schubert's Winterreise - a composed interpretation" for tenor and small orchestra (world premiere: 1993) closely based on Schubert's tonal language and incorporating effective alienating sound effects, which reflect the icy cold and metaphysical gloom of the work.

Another orchestral arrangement was made by the Japanese Yukikazu Suzuki. It was intended for Hermann Prey , who premiered it in Bad Urach in 1997 .

An arrangement for guitar is by Rainer Rohloff . The world premiere took place in Berlin in 2009. He performed it together with the actor Jens-Uwe Bogadtke in February / March 2010 on a tour of Germany.

Based on a version for viola and piano by Tabea Zimmermann , the Austrian violist Peter Aigner has also arranged Winterreise for viola, but its arrangement is supplemented by a scenic realization of the texts by Wilhelm Müller by an actor. This version has already seen several performances in Austria and Germany.

The Austrian composer and hurdy-gurdy player Matthias Loibner arranged Winterreise for hurdy-gurdy and soprano and has performed it in this arrangement since 2009 with the soprano Nataša Mirković-De Ro .

The Greek-Austrian composer Periklis Liakakis arranged the first section of the work in 2007 and the second section in 2012 for the line-up of baritone-viola-cello-double bass. The new work is entitled Winter.reise.bilder - a Schubert overpainting .

Based on the model of Franz Schubert's song cycle, Hans Steinbichler shot the film “Winterreise” in 2006 with Josef Bierbichler and Hanna Schygulla .

The deaf actor Horst Dittrich translated the text of the song cycle into Austrian sign language in 2007 and performed it in 2008 and 2009 in Vienna, Salzburg and Villach in a production of the ARBOS - Society for Music and Theater with the pianist Gert Hecher and the bass baritone Rupert Bergmann up.

Since 2009, the author Stefan Weiller has been combining the life stories of homeless and socially excluded people with the song cycle as part of a music and text performance for the benefit of social organizations in the art project Deutsche Winterreise .

The cantor and composer Thomas Hanelt arranged twelve pieces of the cycle for mixed choir and piano in 2011.

In Bertolt Brecht's early drama Baal (first version 1918) there are clear references to the winter journey . Like the wanderer, Brecht's protagonist is on the way from civilization to death.

The Austrian writer and playwright Elfriede Jelinek published a text for the theater in 2011 with the title Winterreise , which thematically and structurally relates to the song cycle. Jelinek received the Mülheim Dramatist Prize for this .

I moved in the string quartet, Fremd bin ich einzugang, composed by the Swiss composer Alfred Felder ... Variations on the song Gute Nacht from Franz Schubert's Winterreise was a commission from the Musikkollegium Winterthur and has already been performed several times, also available on CD.

In 2020 Deutschlandfunk Köln will present a new production of Augst & Daemgen's Winterreise . The program Atelier neue Musik says: Hardly any recording of the Winterreise cycle deals with Müller's texts and Schubert's music as radically different as the reading of the composers and interpreters Oliver Augst and Marcel Daemgen. In the foreground of the arrangements is not the brilliantly polished beautiful sound of centuries-old traditional musical tradition, but its strict break-through in order to gain a new, undisguised access to the topicality of old texts and the core of the music.

Recordings (selection)

- Richard Tauber , tenor ; Mischa Spoliansky , piano; 1927 (abbreviated)

- Gerhard Hüsch , baritone ; Hans Udo Müller , piano; 1933

- Karl Schmitt-Walter , baritone; Ferdinand Leitner , piano; 1940 Telefunken (unpublished), Preiserrecords

- Hans Hotter , baritone; Michael Raucheisen , piano; 1942

- Peter Anders , tenor; Michael Raucheisen, piano; 1945

- Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau , baritone; Klaus Billing, piano; 1948 RIAS (1988 Movimento Musica srl Milano)

- Peter Anders, tenor; Günther Weißenborn , piano; 1948

- Karl Schmitt-Walter , baritone; Hubert Giesen , piano; 1952 DECCA

- Hans Hotter, baritone; Gerald Moore , piano; 1955 EMI

- Josef Greindl , bass ; Hertha Klust , piano; 1957 DGG

- Hermann Prey , baritone; Karl Engel , piano; 1962

- Gérard Souzay , baritone; Dalton Baldwin , piano; 1962 Philips

- Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau , baritone; Gerald Moore, piano; 1963 EMI

- Julius Patzak , tenor; Jörg Demus , piano; 1964 prize records

- Peter Pears , tenor; Benjamin Britten , piano; 1965 DECCA

- Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Jörg Demus, piano; 1966 DGG

- Rudolf Schock , tenor; Iván Eröd , piano; 1970 EURODISC / BMG

- Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Gerald Moore, piano; 1971 DGG

- Hermann Prey, baritone; Wolfgang Sawallisch , piano; 1971 Philips

- Theo Adam , bass-baritone ; Rudolf Dunkel, piano; 1974

- Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Maurizio Pollini , piano; 1978 Orfeo

- Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Daniel Barenboim , piano; 1980

- Robert Holl , bass-baritone; Konrad Richter, piano; 1980

- Engelbert Kutschera, bass; Jörg Demus , piano; 1980

- Siegfried Vogel , bass; Rudolf Dunckel, piano; 1983 VEB Deutsche Schallplatten Berlin (2006 Berlin Classics / Edel)

- Hermann Prey, baritone; Philippe Bianconi, piano; 1984 Denon

- Peter Schreier , tenor; Svyatoslaw Richter , piano; 1985

- Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Alfred Brendel , piano; 1985 Philips

- Eberhard Büchner , tenor; Norman Shetler , piano; 1985

- Siegfried Lorenz , baritone; Norman Shetler, piano, 1986

- Christa Ludwig , mezzo-soprano ; James Levine , piano; 1988 DGG

- Kurt Equiluz , tenor; Margit Fussi, Fortepiano, 1988

- Thomas Quasthoff , baritone; Martin Galling, piano, 1989

- Brigitte Fassbaender , mezzo-soprano; Aribert Reimann , piano; 1990; see also films

- Peter Ziethen , baritone; Tadashi Sasaki , guitar; 1991 VMK

- Andreas Schmidt , baritone; Rudolf Jansen, piano; 1992 DGG

- Peter Schreier , tenor; András Schiff , piano, 1994

- Robert Holl , bass-baritone; Naum Grubert, piano; 1995

- Mitsuko Shirai , mezzo-soprano ; Hartmut Höll , piano; 1996 Capriccio

- Harry Geraerts , tenor; Ludger Rémy , piano, 1997 MD + G

- Anton Dermota , tenor; Hilda Dermota , piano, 1997 Preiser

- Matthias Goerne , baritone; Graham Johnson, piano; 1997 Hyperion

- Thomas Hampson , baritone; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano; 1997 EMI

- Christoph Prégardien , tenor; Andreas Staier , fortepiano ; 1997 Teldec

- Thomas Quasthoff , baritone; Charles Spencer , piano; 1998 RCA

- Roland Hartmann, baritone; Christian Frank, piano; 1999

- Christian Gerhaher , baritone; Gerold Huber , piano; 2001

- Mario Hacquard, baritone; Georges Dumé, piano; 2001 Hybrid'Music

- Ian Bostridge , tenor; Leif Ove Andsnes , piano; 2004 EMI Classics; see also films

- Matthias Goerne, baritone; Alfred Brendel, piano; 2004 Universal

- Nathalie Stutzmann , contra-alto ; Inger Södergren , piano; 2004 Caliope / rbb Berlin

- Constantin Walderdorff, bass baritone; Kristin Okerlund, piano; 2004 Preiser Records Vienna

- Thomas Quasthoff, baritone; Daniel Barenboim, piano; DVD; 2005 Universal

- Peter Schreier , tenor; Dresden String Quartet (arr. Jens Josef ); 2005 MDR FIGARO

- Christine Schäfer , soprano; Eric Schneider , piano; 2006 PM Classics Onyx

- Thomas E. Bauer , baritone, Siegfried Mauser , piano; 2006 OehmsClassics ("Schubert in Siberia")

- Hans Jörg Mammel , tenor, Arthur Schoonderwoerd , fortepiano ; Fall 2006 alpha

- Florian Prey , baritone, Rico Gulda , piano; 2006 Orpliod

- Michael Volle , baritone, Urs Liska , piano; 2007 animato

- Tom Franke , bass-baritone; Newena Popow , piano; 2007 ARS production

- Dominik Wörner , bass baritone; Christoph Hammer , fortepiano; 2007 blumlein production

- Matthias Horn, baritone, Christoph Ullrich, piano; 2009 Spectral label

- Mark Padmore , tenor; Paul Lewis , piano; 2009 Harmonia mundi

- Thomas E. Bauer, baritone; Jos van Immerseel , Fortepiano Christopher Clarke, 1988, Cluny, 2009 Zig-Zag Territoires

- Adrian Eröd , baritone; Eduard Kutrowatz, piano; 2010 Gramola

- Nataša Mirkovic-de Ro, soprano; Matthias Loibner , hurdy-gurdy ; 2010 Raumklang (Harmonia Mundi)

- James Gilchrist , tenor; Anna Tilbrook, piano; 2011 ORCHID Classics

- Christoph Prégardien , tenor; Michael Gees , piano; 2013 Challenge Classics

- Jonas Kaufmann , tenor; Helmut Deutsch , piano; 2014 Sony Music

- Heinz Zednik , tenor; Markus Vorzellner, piano; 2015 Bock Productions

- Ronald Hein, tenor; Hiroto Saigusa, piano; 2018 SAEK video production

- Philippe Sly, bass-baritone; Chimera Project, chamber ensemble; 2019 Analekta

- Pavol Breslik , tenor; Amir Katz , piano; 2019 Orfeo

Film adaptations

- 1994: Winterreise by Petr Weigl with Brigitte Fassbaender.

- 1997: Winterreise by David Alden with Ian Bostridge (tenor) and Julius Drake (piano).

literature

- Ian Bostridge : Schubert's Winter Journey. Songs of love and pain. CH Beck, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-406-68248-3 .

- Elmar Budde : Schubert's song cycles. A musical factory guide. CH Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-44807-0 .

- Andreas Dorschel : Wilhelm Müller's “The Winter Journey” and the promise of redemption of romanticism. In: The German Quarterly LXVI (1993), No. 4, pp. 467-476.

- Arnold Feil : Franz Schubert. “The beautiful miller”, “Winterreise”. Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-15-010421-1 .

- Veit Gruner: Expression and effect of harmony in Franz Schubert's "Winterreise" - analyzes, interpretations, teaching suggestions. The Blue Owl, Essen 2004, ISBN 3-89924-049-9 .

- Jürgen Hillesheim : Who is the Leiermann? On the central figure of the “Winterreise” by Wilhelm Müller and Franz Schubert. In: Ars et Scientia I (2015), pp. 19-27.

- Jürgen Hillesheim: "I moved in as a stranger, I move out again ..." Brecht's "Baal" and "Die Winterreise" by Wilhelm Müller and Franz Schubert. In: German Life and Letters LXIX (2016), 2, pp. 160-174.

- Jürgen Hillesheim: From the “Dorfe” to the “Stormy Morning”. To two songs from Wilhelm Müller and Franz Schubert's “Die Winterreise”. In: Studia theodisca XXIII (2016), pp. 5–16.

- Jürgen Hillesheim: The hike to “ nunc stans ”. Wilhelm Müller and Franz Schubert's “The Winter Journey” . Rombach, Freiburg im Breisgau 2017, ISBN 978-3-7930-9849-2 .

- Jürgen Hillesheim: Wilhelm Müller and Franz Schubert, winter trip. In: Günter Butzer, Hubert Zapf (ed.): Great works of world literature. Vol. 14. Tübingen 2017, pp. 53–68.

- Wolfgang Hufschmidt : Do you want to twist your lyre to my songs? On the semantics of musical language in Schubert's "Winterreise" and Eisler's "Hollywood songbook". Pfau-Verlag, Saarbrücken 1997, ISBN 3-930735-68-7 .

- Werner Kohl: Wilhelm Müller's “The Winter Journey” or how poetry is made. Self-published, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-00-009589-6 .

- Ingo Müller: “One in all and all in one.” On the aesthetics of the cycle of poems and songs in the light of romantic universal poetry. In: Günter Schnitzler , Achim Aurnhammer (ed.): Word and sound. Rombach, Freiburg i. Br. 2011, ISBN 978-3-7930-9601-6 . Pp. 243-274.

- Margret Schütte: I have to show me the way ... In: Ingo Kühl : Winterreise . Berlin 1996, DNB 994097344 , pp. 53-55.

- Rita Steblin : Schubert's Unhappy Love for Gusti Grünwedel in Early 1827 and the Connection to Winterreise. Her Identity Revealed. In: Schubert: Perspectives. Volume 12, 2012, Issue 1, ISSN 1617-6340 .

- Christiane Wittkop: Polyphony and Coherence. Wilhelm Müller's cycle of poems "Die Winterreise". M & P Verlag for Science and Research, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-476-45063-5 .

Web links

- Winter Journey : Sheet Music and Audio Files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Winter Journey Score at Indiana University

- Facsimile at the Morgan Library & Museum

- Song lyrics in translations at The LiederNet Archive

- Winterreise: Songs, Articles, Recordings, Links (English)

- Recitation of the text at LibriVox (No. 20)

- "... what do I want to hem under the sleepers?" Thoughts on Schubert's winter trip from Achim Goeres

References and footnotes

- ↑ the small volume is "dedicated to the master of German singing Carl Maria von Weber as a pledge of his friendship and admiration"

- ↑ Erika von Borries, Florian Prey, Gert Westphal : Wilhelm Müller - The poet of winter travel. A biography. CH Beck, 2007, pp. 150, 151.

- ^ Frieder Reininghaus : Schubert and the tavern. Music under Metternich ; Wolfgang Hufschmidt: You want to turn your lyre to my songs.

- ↑ Achim Goeres: ... what do I want to hem under the sleepers? Thoughts on Schubert's winter journey. Manuscript, Berlin 2001.

- ↑ Reinhold Brinkmann: Musical lyric poetry, political allegory and the "holy art". In: Archives for Musicology . 62, 2005, pp. 75-97.

- ↑ Jürgen Hillesheim: The hike to the "nunc stans". Wilhelm Müller and Franz Schubert's “The Winter Journey”. Rombach, Freiburg 2017, p. 17-24, 47-59 .

- ^ Harry Goldschmidt: Schubert's "Winterreise". In: About the cause of music - speeches and essays. Philipp Reclam jun., Leipzig 1970, pp. 100 and 111.

- ↑ a b Harry Goldschmidt: Schubert's "Winterreise". In: About the cause of music - speeches and essays. Reclam, Verlag Philipp Reclam jun. Leipzig, 1970, p. 111.

- ↑ a b Elmar Budde: Schubert's song cycles. A musical factory guide. CH Beck, 2003, p. 67.

- ↑ Susan Youens: Retracing a Winter's Journey: Franz Schubert's "Winterreise". Cornell University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-8014-9966-6 , p. 125.

- ↑ Susan Youens: Retracing a Winter's Journey: Franz Schubert's "Winterreise". Cornell University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-8014-9966-6 , p. 132.

- ↑ Elmar Budde: Schubert's song cycles - a musical work guide , CH Beck, 2003, p. 79.

- ↑ Schubert himself spoke to his friends - as Joseph von Spaun reports - in the autumn of 1827 of “a circle of gruesome songs” that he would sing to them at the next meeting (→ Schubertiaden ).

- ↑ Susan Youens: Retracing a Winter's Journey: Franz Schubert's "Winterreise". Cornell University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-8014-9966-6 , p. 139.

- ↑ Susan Youens: Retracing a Winter's Journey: Franz Schubert's "Winterreise". Cornell University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-8014-9966-6 , p. 145.

- ↑ Ludwig Stoffels: The winter journey: The songs of the first section. Verl. F. Systemat. Musikwiss., 1991, ISBN 3-922626-62-9 , p. 13, with reference to Zenck's competing interpretation as cardinal virtues.

- ↑ Susan Youens: Retracing a Winter's Journey: Franz Schubert's "Winterreise". Cornell University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-8014-9966-6 , p. 291.

- ↑ Susan Youens: Retracing a Winter's Journey: Franz Schubert's "Winterreise". Cornell University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-8014-9966-6 , p. 297.

- ↑ Peter Gülke: Franz Schubert und seine Zeit , Laaber-Verlag, 2nd edition of the original edition from 1996, 2002, p. 236.

- ↑ Michael Lorenz: The Continuing Mutilation of Schubert's “Der Leiermann” , Vienna 2013.

- ↑ Franz Liszt: The Leiermann and deception, transcription for pianoforte. Tobias Haslinger, Vienna 1840 : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project .

- ^ Arnold Feil, Rolf Vollmann: Franz Schubert - The beautiful miller, winter trip, Wilhelm Müller and romanticism . Reclam, Leipzig 1975, p. 202.

- ↑ schuberts-winterreise.de .

- ^ Illusion by Franz Schubert and Wilhelm Müller , interpreted by Horst Dittrich, Rupert Bergmann and Gert Hecher, on dailymotion.com.

- ↑ Cf. Jürgen Hillesheim: "Strange I moved in, stranger I move out again ..." Brechts Baal and Die Winterreise by Wilhelm Müller and Franz Schubert. In: . In: German Life and Letters . LXIX, 2, 2016, p. 160-174 .

- ↑ Die Winterreise (Weigl) in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ↑ Winterreise (Alden) in the Internet Movie Database (English)