Lapis Niger

The lapis Niger ( Latin for "black stone") is a square area made of black marble slabs on the Roman Forum in Rome , under which a stele with an inscription and broken off at the top was found. This is called the Forum Cippus and sometimes incorrectly called Lapis Niger . The inscription on this stone, written in ancient Latin, consists of remains of a cult law ( lex sacra ) and refers to either a king ( rex ) or a sacrificial king ( rex sacrorum ), an official responsible for religious ceremonies in the early Roman Republic . The information on the chronological classification fluctuates greatly, but new research puts a date in the 7th or 6th century BC. BC, so probably still in the Roman royal era , close.

Archaeological evidence

The Lapis Niger was discovered in May 1899 by the archaeologist Giacomo Boni during excavation work on the Roman Forum. It is located between the Arch of Septimius Severus and Iulia Curia , near the Forum's republican rostra . The part of the complex that is still visible today is a 3.5 x 4 m area made of black, 25 to 30 cm thick marble slabs , from which the name Lapis Niger is derived. Their dates are given very differently; the proposals range from the 1st century BC. Until the 4th century AD

An early Roman building complex was found about 1.4 m below these stone slabs: This consisted of remains of an altar, which originally apparently belonged to the Volcanal , a sanctuary of the fire god Vulcanus , and of a square inscription stone ( Cippus ). An archaeological finds several were votive offerings , small sculptures, ceramic pieces and many bones of cattle, sheep and pigs to light.

The Vulcanus Altar and the Cippus are believed to be the only remains of the old Comitium of the City of Rome, an early meeting place that was a forerunner of the Forum and in turn from an archaic cult site of the 8th or 7th century BC. Had emerged. This cultic site was already at the center of public life in the earliest times of Rome. The fact that it was not destroyed many centuries later when the forum was expanded, but rather carefully covered with conspicuous stone slabs, shows that special importance was still attached to it at that time. Presumably one knew about the special age of the place of worship underneath and therefore understood it as a relic of one's own early days. At the same time, however, it was probably not clear at that time what function the findings from Lapis Niger had originally, since attempts were made to associate them with different mythological personalities (see the chapter Mention in ancient written sources ).

Mentioned in ancient written sources

Several ancient written sources mention a monument at the Comitium or the Roman Forum and link it to various personalities from mythical early Roman history. Some of the texts mention a Lapis Niger , others only give the approximate position. According to the poet Horace , the tomb of the mythical city founder and first Roman king Romulus was located at the forum. Two ancient commentaries ( Scholien ) on the work of the writer give more precise information: The Horace Scholion of Pomponius Porphyrio locates the Romulus tomb behind the Rostra ("post rostra"), the corresponding work of the "Pseudo-Acron" near the Rostra ( "In Rostris"). Both refer to the work of the scholar Marcus Terentius Varro as a source, but the corresponding passage from it is not directly preserved. Pseudo-Acron also mentions two lions that are said to have flanked the tomb, and explains that the nearby tomb of the city founder gave rise to the custom of holding public funeral speeches for deceased Romans in front of the Rostra .

The lexicographer Sextus Pompeius Festus gives in his treatise De verborum significatu ("On the meaning of words") more detailed explanations of the "Niger lapis":

- "Niger lapis in comitio locum funestum significat, ut ali, Romuli morti destinatum, sed non usu obv [enisse, ut ibi sepeliretur, sed Fau] stulum nutri [cium eius, ut ali dicunt Hos] tilium avum Tu [lli Hostilii, Romanorum regis ] "

- “The black stone on the Comitium marks a burial place which, as some say, was intended for the corpse of Romulus, but that it did not happen that he was buried there, but that his foster [father Fau] stulus , [but, as the others say, Hos] tilius, the grandfather of Tu [llus Hostilius, king of the Romans]. "

Festus cites the two assumptions circulating at the time that either Faustulus , the foster father of Romulus and his brother Remus, or Hostus Hostilius , the grandfather of the third mythical Roman king Tullus Hostilius , was buried under the lapis Niger . The ancient historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus also located a lion statue regarded as the burial of Faustulus and the inscribed grave of Hostus Hostilius in the Roman Forum at two different places in his work, the first "near the Rostra", the second not further specified position in the main part of the forum. In a third passage, Dionysius mentions an inscribed account of the facts of Romulus, which is located near a place of sacrifice for Vulcanus and is written in Greek letters. It was suspected that this was the cippus at Lapis Niger and that the historian interpreted the archaic alphabet used on it as Greek letters.

However, the archaeological investigations have shown that the building remains at Lapis Niger did not belong to a tomb or a political monument (as one would imagine as a site for a report of deeds), but to an altar. The information in the ancient written sources is therefore probably about etiologies , i.e. mythical stories that the Romans developed in later times in order to somehow explain a venerable building in the city center and an inscription on it that they do not understand. At the same time, however, all of this seems to have been various, inconsistent speculations of a rather diffuse character, since a complex traditionally and generally interpreted as a Romulus grave would hardly have simply been paved over.

Another potential connection to the mythical early history of Rome is made by the report in the Romulus biography of Plutarch , who claims that Romulus was murdered in the sanctuary of Vulcanus ("ἐν τῷ ἱερῷ τοῦ Ἡφαίστου "). However, it does not have to be the Volcanal on the Roman Forum, but there are some indications that a Vulcanus sanctuary founded by Romulus outside the city is meant there.

The "Forum Cippus"

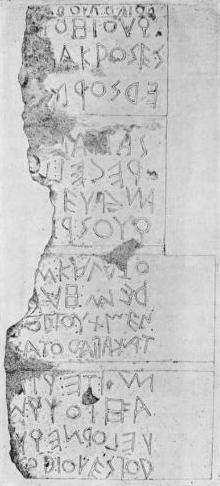

Description of the stone

The stele is made of dark tuff from the Veji area ; it has a base of 47 cm × 52 cm and a height of between 45 cm and 61 cm. It should have originally been a rectangular column, the upper part of which was cut off - presumably when the stone slabs found above were laid. The writing is " bustrophedon " (literally: "how the ox walks when plowing"), which means that the direction of writing alternates between the lines. The peculiarity of the Cippus under the Lapis Niger is that the direction of writing does not change between left and right, but the text is written vertically from bottom to top or from top to bottom. Exceptions are the eleventh and twelfth lines of the inscription, which both run in the same direction. This design, which is rather impractical for reading the text, could have had religious or cultic reasons.

All four sides of the stone are described, they are referred to as sides A to D. When the scribe realized - probably only in the course of the chiselling - that there would not be enough space for the text to be accommodated, he sloped the corner between side D and side A and put the last line in smaller font on this edge. The letter height therefore fluctuates greatly and is between 12.4 and 3.5 cm. How much of the inscription was lost when the upper part was knocked off cannot be determined.

Dating

An extensive research discussion has arisen about the dating of the inscription, in which various historical, linguistic, palaeographic and archaeological arguments are brought into the field. An early approach dates the stone to the Roman royal era , which lasted until the end of the 6th century BC. Chr. Was enough. If this assumption is correct, the text on it represents one of the oldest surviving inscriptions in Latin. Other scholars contradict this thesis and represent dates from significantly later epochs up to the time after the Gaul storm at the beginning of the 4th century BC. Occasional supposedly very precise time indications for the origin of the stone - such as narrowing it down to a few decades - result from the tempting combination of several uncertain clues that seem to confirm each other, and are therefore pure speculation.

The historical considerations are based on the one hand on the vocabulary "recei" (which is interpreted as the declined form of the Latin "rex", "king") and "kalatorem" (from "kalator", Latin for "servant, crier"). If one assumes that "rex" means the city king of the early Roman period and "kalator" means one of his officials, the inscription dates back to the royal era, i.e. the late 6th century BC at the latest . To date. “Rex” can just as well be related to the rex sacrorum , one of the highest priesthoods of the early Roman republic, and the “kalator” can be understood as one of his helpers. For the dating, this would be the exact opposite, i.e. a location in the republican epoch and thus at the earliest the late 6th century BC. Mean. A second category of historical arguments for the temporal fixation of the “Forum-Cippus” is based on equating the buildings found under the inscription stone with monuments that are mentioned in ancient written sources (see chapter Mention in ancient written sources ). However, since these reports are not uniform among each other and the excavation findings - a remnant of an archaic sanctuary probably belonging to the god Vulcanus - do not confirm any of them, it is not possible to use them for a reliable dating.

On the one hand, the various accompanying finds that came to light during the excavations are used as archaeological clues for dating the inscription stone . Various fragments of Corinthian pottery can be dated particularly well from them ; they date from the 6th century BC. However, like the other finds from the area around Lapis Niger, they have the problem that it cannot be said with certainty whether they ended up in the ground during the period of use of the cult facility, for example as a votive offering , or later as material were used for filling or came to their place of discovery through alluvial deposits. On the other hand, from the archaeological point of view, the main argument is the stratigraphic context of the stone. This includes its altitude and orientation as well as its relative position in comparison to neighboring, above and below findings. However, these clues suffer from the fact that the adjacent buildings cannot be dated with certainty either. Even if it is clear that one of them was created later or earlier than the Cippus, this only offers a relative chronological clue , even in the best case .

The inscription itself gives various linguistic ( archaisms , grammar) and external (direction of writing, letter forms, punctuation) indications, which, however, also do not offer any reliable information about the period of origin, but at most clues. For example, old letter forms often persisted for a long time after the development of new spellings, so when comparing two inscriptions, the text with the historically earlier letters does not automatically have to be the actually older one. For a later dating of the Forum-Cippus it was finally stated that the tuff rock from which it is made was only more easily accessible to the Romans at the beginning of the 4th century, when they had conquered the city of origin, Veji.

None of these approaches lead to a clear classification. A reasonably safe indication of an early dating is a water basin that was found during renewed excavations in 1955 and must have been filled in shortly before the Vulcanus altar was built. According to the bulk material found, this happened in the 6th century BC. BC, which provides the earliest possible point in time ( terminus post quem ) for the erection of the altar. A point where its foundation meets the foundation of the inscription column, in turn, gives a relatively reliable indication that the latter is older, i.e. probably originated in the 6th century or earlier. This assessment also corresponds to more recent systematic comparisons of the letter forms with those of other early Latin inscriptions.

labeling

The remaining parts of the inscriptions on pages A to D as well as on the area between A and D read (in reading direction, reproduced according to the Leiden bracket system ):

Side A: "Quoi hoṇ [––] / [––] ṣakros es / ed sord [––]"

Side B: "[––] a ḥas / recei iọ [––] / [––] evam / quos rẹ [––]"

Side C: "[––] ṃ kalato / rem haḅ [––] / [––] ṭod iouxmen / ta kapia duo tau [––]"

Side D: "[––] ạm iter p̣ẹ [––] / [––] ṃ quoi ha / velod neq f̣ [––] / [––] ịod iovestod"

Between side A and D: "loiuquiod qo ["

A few words are almost certainly recognizable. This includes a king ( recei , see the classic form rex with the dative regi ), (s) a herald or crier ( kalatorem , see the classic form calator with the accusative calatorem ), a draft animal ( iouxmenta , see the classic form iumentum with the plural iumenta ) and a curse or sanctification ( sakros esed , see the classical form sacer esto ).

Completion and interpretation

The additions to the inscription are not clear. Some do not result from general linguistic probabilities in completing what has been preserved, but only from the presumed interpretation of the inscription as a sacred law. This applies, for example, to the addition of the last two letters QO to qomitium , an archaic form of the term comitium for the Roman people's assemblies. Robert EA Palmer presented an extensive study of the inscription in 1969 and came to the following additions partly through linguistic-historical considerations, but also through comparisons with other sanctuary laws of the republican era that have been handed down in writing:

Side A: “quoi hon [ce louquom violasit] / [––] sacros es- / ed. sord [es nequis fundatod neve] "

Side B: "[kadaver proikitod ---] a has / recei io [us esed bovid piaklom fhakere.] / [Moltatod moltam pr] evam. / quos re [x moltasid, boves dantod.] "

Side C: "[rex ---] m kalato- / rem hab [etod.] / [Iounki] tod iouxmen- / ta kapia duo tau [r ---]"

Side D: "am iter pe [r ---] / [eu] m quoi ha- / velod neq f [hakiat] / [en ---] iod iovestod"

Between page A and D: "louquiod qo [miti ---]"

This brings him to a tentative English translation, which is reproduced here in a German version:

- Whoever hurts this [grove] shall be cursed. [Let no one] throw garbage or throw a body (in the sense of "burying a corpse") ... Let it be lawful for the king to [sacrifice a cow as an atonement. Let him] take a [punishment] for every [offense]. Whom the king [will punish, let him give cows. Let the king have a…] messenger. Let him [harness] a team of two pieces (cattle), sterile ... Along the processional path ... [Him] who will not [sacrifice] a young animal ... in a ... legitimate public assembly in a grove.

(The square brackets mark terms of which no part has been preserved in the Latin text, i.e. which Palmer reconstructed purely for historical considerations or on the basis of comparable inscriptions from a somewhat later period. In round brackets there are linguistic additions that Palmer's draft English translation in To make Germans more understandable; they are based on his other considerations and explanations about the inscription.)

It is a temple law that regulates the atonement of the king or priest-king in a sacred grove. Palmer suspects that the ruler or the clergyman should have gone there in a procession. The messenger or herald also mentioned in the text was an official who had been sent ahead of the (priest) king and had to ensure that the ceremony was not impaired by "unclean" things along the processional path. These far-reaching additions to the inscription by Palmer are partly based on interpretations of the content and cannot in every case be inferred directly from the inscription itself. Therefore, not all researchers agree with Palmer's attempt at completion and translation. For example, Markus Hartmann remarks in his study on early Latin inscriptions published in 2005 about the Forum-Cippus: "With the exception of a few individual words [...] - the inscription closes itself off from a reliable overall translation."

literature

- Sepulcrum Romuli. In: Samuel Ball Platner : A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Completed and revised by Thomas Ashby . Oxford University Press, London 1929, pp. 482-484, online at LacusCurtius.

- Johannes Stroux : The forum inscription at Lapis niger. In: Philologus . Volume 86, Number 4, 1931, pp. 460-491.

-

On the problem of the forum inscription under the Lapis Niger (= Klio . Supplements. Volume 27 = New Series Volume 14, ISSN 1438-7689 ). Dieterich, Leipzig 1932 (contains:

- 1. Franz Leifer: Two recent solutions (Graffunder and Stroux).

- 2. Emil Goldmann: attempted interpretation. )

- Robert EA Palmer: The king and the comitium. A study of Rome's oldest public document (= Historia . Individual writings. Volume 11). Franz Steiner, Wiesbaden 1969.

- Filippo Coarelli : Il Foro Romano. Volume 1: Periodo arcaico. Ed. Quasar, Rome 1983, ISBN 88-85020-44-5 , pp. 161-188.

- Rudolf Wachter : Old Latin inscriptions. Linguistic and epigraphic studies of the documents up to around 150 BC Chr. (= European university publications. Series 15: Classical languages and literature. Volume 38). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 3-261-03707-5 , pp. 66-69 (also dissertation, University of Zurich 1986/1987).

- Daniela Urbanová: The two most important ancient Latin inscriptions from Rome of the 6th century BC R. In: Sborník prací Filozofické fakulty brněnské univerzity. Volume 38, 1993, pp. 131-139 ( PDF ).

- Filippo Coarelli: Sepulcrum Romuli. In: Eva Margareta Steinby (Ed.): Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae . Volume 4: P-S. Quasar, Rome 1999, ISBN 88-7140-135-2 , p. 295 f.

- Hartmut Galsterer : Lapis niger. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 6, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01476-2 , Sp. 1142.

- Theodor Kissel : The Roman Forum. Living in the heart of the city. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf et al. 2004, ISBN 3-7608-2307-6 , pp. 36-38.

- Markus Hartmann: The early Latin inscriptions and their dating. A linguistic-archaeological-palaeographic investigation (= Munich research on historical linguistics. Volume 3). Hempen Verlag, Bremen 2005, ISBN 3-934106-47-1 , especially pp. 122–130, pp. 192–197, pp. 211 f., P. 217 f., Pp. 252–256 and p. 336 –343 (also dissertation, Julius Maximilians University of Würzburg 2003/2004).

Individual evidence

- ↑ For the place where the Lapis Niger was found, see Giuseppe Lugli: Roma Antica. Il centro monumentale. Bardi, Rome 1946, pp. 115-131.

- ^ Oskar Viedebantt : Forum Romanum (buildings). In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Supplement volume IV, Stuttgart 1924, Col. 461-511, here Col. 490 f.

- ^ Christian Hülsen : Annual report on new finds and research on the topography of the city of Rome. New episode. I: The excavations in the Roman Forum 1898–1902. In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Roman Department . Volume 17, 1902, pp. 1-97, here p. 30 f.

- ↑ A brief description of the findings is provided by Oskar Viedebantt : Roman Forum (Buildings). In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Supplement volume IV, Stuttgart 1924, Col. 461-511, here Col. 490 f.

- ^ A b Filippo Coarelli : Il Foro Romano. Volume 1: Periodo arcaico. Ed. Quasar, Rome 1983, ISBN 88-85020-44-5 , pp. 161-178.

- ^ Theodor Kissel: The Roman Forum. Living in the heart of the city. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf et al. 2004, pp. 36–38.

- ↑ Johannes Stroux: The forum inscription at the Lapis niger. In: Philologus. Volume 86, number 4, 1931, pp. 460-491, here p. 461.

- ↑ Horace , Epoden 16,13 f.

- ↑ Pomponius Porphyrio , Scholion zu Horace, Epoden 16,13 ( online ).

- ↑ Pseudo-Acron , Scholion zu Horace, Epoden 16,13.

- ↑ Markus Hartmann: The early Latin inscriptions and their dating. A linguistic-archaeological-paleographic investigation. Hempen Verlag, Bremen 2005, ISBN 3-934106-47-1 , p. 211 f.

- ^ Dionysius of Halicarnassus , Römische Altert becoming 1,87,2 ( English translation of the passage ).

- ↑ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman antiquities 3,1,2 ( English translation of the passage ).

- ↑ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman antiquities 2,54,2 ( English translation of the passage ).

- ↑ Hartmut Galsterer : Lapis niger. In: Der Neue Pauly (DNP). Volume 6, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01476-2 , Sp. 1142 (the information about the Dionysios passage there with a typo).

- ↑ Carmine Ampolo: La Storiografia su Roma Arcaica ei Documenti. In: Emilio Gabba (Ed.): Tria Corda. Scritti in onore di Arnaldo Momigliano (= Bibliotheca di Athenaeum. Volume 1). Edizioni New Press, Como 1983, pp. 9-26, here pp. 19-26.

- ↑ Markus Hartmann: The early Latin inscriptions and their dating. A linguistic-archaeological-paleographic investigation. Hempen Verlag, Bremen 2005, ISBN 3-934106-47-1 , p. 212.

- ↑ Andreas Hartmann : Between relic and relic. Object-related memory practices in ancient societies (= studies on ancient history. Volume 11). Verlag Antike, Heidelberg 2010, ISBN 978-3-938032-35-0 , p. 302 f. A significantly greater significance for the self and historical consciousness of the Romans is ascribed to the Lapis Niger by Hans Beck : Hans Beck: The Discovery of Numa's Writings: Roman Sacral Law and the Early Historians. In: Kaj Sandberg, Christopher Smith (eds.): Omnium annalium monumenta. Historical writing and historical evidence in Republican Rome (= Historiography of Rome and its Empire. Volume 2). Brill, Leiden / Boston 2018, ISBN 978-90-04-35544-6 , pp. 90–114, here p. 91.

- ↑ Rene Pfeilschifter : The Romans on the run. Republican celebrations and the creation of meaning through aitiological myth. In: Hans Beck, Hans-Ulrich Wiemer (Ed.): Celebrating and remembering. Historical images in the mirror of ancient festivals (= studies on ancient history. Volume 12). Verlag Antike, Heidelberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-938032-34-3 , pp. 109-139, here p. 121 f. with note 45 (Pfeilschifter, however, also rejects the equation of Volcanal and Lapis Niger proposed by Coarelli).

- ^ Robert EA Palmer: The king and the comitium. A study of Rome's oldest public document. Franz Steiner, Wiesbaden 1969, p. XI.

- ↑ a b Markus Hartmann: The early Latin inscriptions and their dating. A linguistic-archaeological-paleographic investigation. Hempen Verlag, Bremen 2005, ISBN 3-934106-47-1 , p. 129.

- ↑ a b For the divergent dates see: Markus Hartmann: Die early Latin inscriptions and their dating. A linguistic-archaeological-paleographic investigation. Hempen Verlag, Bremen 2005, ISBN 3-934106-47-1 , especially p. 130.

- ↑ For the historical arguments on dating see Markus Hartmann: Die early Latin inscriptions and their dating. A linguistic-archaeological-paleographic investigation. Hempen Verlag, Bremen 2005, ISBN 3-934106-47-1 , p. 211 f.

- ↑ For the archaeological arguments on dating see Markus Hartmann: Die early Latin inscriptions and their dating. A linguistic-archaeological-paleographic investigation. Hempen Verlag, Bremen 2005, ISBN 3-934106-47-1 , p. 195.

- ↑ Markus Hartmann: The early Latin inscriptions and their dating. A linguistic-archaeological-paleographic investigation. Hempen Verlag, Bremen 2005, ISBN 3-934106-47-1 , p. 217 f.

- ^ Rudolf Wachter : Old Latin inscriptions. Linguistic and epigraphic studies of the documents up to around 150 BC Chr. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 3-261-03707-5 , p. 67 f.

- ↑ Luciana Aigner-Foresti : The Etruscans and early Rome. 2nd, revised edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-534-23007-5 , p. 95.

- ↑ Markus Hartmann: The early Latin inscriptions and their dating. A linguistic-archaeological-paleographic investigation. Hempen Verlag, Bremen 2005, ISBN 3-934106-47-1 , pp. 195-197.

- ↑ Markus Hartmann: The early Latin inscriptions and their dating. A linguistic-archaeological-paleographic investigation. Hempen Verlag, Bremen 2005, ISBN 3-934106-47-1 , especially pp. 252–256 and pp. 336–343.

- ^ Robert EA Palmer: The king and the comitium. A study of Rome's oldest public document. Franz Steiner, Wiesbaden 1969, p. XII.

- ^ Robert EA Palmer: The king and the comitium. A study of Rome's oldest public document. Franz Steiner, Wiesbaden 1969, p. 49.

- ↑ English translation Palmer: “Whosoever [will violate] this [grove], let him be cursed. [Let no one dump] refuse [nor throw a body…]. Let it be lawful for the king [to sacrifice a cow in atonement.] [Let him fine] one [fine] for each [offense]. Whom the king [will fine, let them give cows.] [Let the king have a ---] herald. [Let him yoke] a team, two heads, sterile ... Along the route ... [Him] who [will] not [sacrifice] with a young animal ... in a ... lawful assembly in a grove ... "See Robert EA Palmer: The king and the comitium. A study of Rome's oldest public document. Franz Steiner, Wiesbaden 1969, p. 49.