Fairy tale of one who set out to learn to fear

The fairy tale of someone who set out to learn to fear is a fairy tale ( ATU 326). It is in place 4 (KHM 4) in the children's and house tales of the Brothers Grimm . In the 1st edition it was called Gut Kegel- und Kartenspiel , up to the 3rd edition it was fairy tales of someone who set out to learn to be afraid . Ludwig Bechstein took it over in his German fairy tale book in 1853 as Das Schuseln in place 80.

content

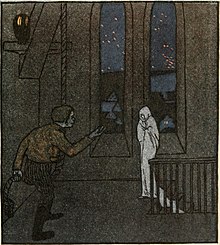

A father has two sons, an elderly capable and a younger simple-minded. The younger one does not understand why his brother and others keep talking about the fact that something "creeps" them. When the father asks the younger son one day to learn to make a living, he suggests that they want to learn how to "scare". The father is at a loss and complains of his suffering to a sexton. The sexton then offers to give the boy a lesson and takes him into his service. When the boy rings the bells at night, the sexton disguises himself as a ghost and tries to scare him. But the boy pushes the supposed ghost down the stairs when it doesn't answer his questions. Then he goes to sleep unmoved. The sexton discovered her husband with a broken leg and complained to the son's father about it. The father then sends his son away into the world. Since the boy keeps talking about his inability to shudder on the way, a man shows him a gallows where he can learn it overnight. But the boy makes a fire and ties the dead to warm them. When her clothes catch fire, he hangs her up again and falls asleep - with no idea what the horror is. A landlord he meets soon after knows about a haunted castle: If you can stay there for three nights, you will get a princess as a wife. Hoping to finally learn how to scare, the boy then goes to the king and takes the test. All he asked for was a fire, a lathe and a carving bench with a knife. On the first night, black cats visit him to play cards, which he keeps in check with the help of a lathe and carving knife when they attack. Then his bed moves around the castle with him, but the boy lies down to sleep on the floor, unmoved. On the second night, two halved human bodies ask him to go bowling. The boy enthusiastically joins in and even carves the skulls into balls. On the third night he lies down in the coffin with a dead man to keep him warm. When the latter attacks him, he throws him away again. At the end of the night an old man comes to kill the boy. Before that, however, there should be a showdown. The boy uses this: he clamps the old man's beard in an anvil and beats him until he promises plenty of treasure. On all these occasions the boy never shudders, as he explains disappointedly to the astonished king every morning. Since the castle's curse is finally broken after the third night, the princess is married. But even after the wedding, the boy complains that he still doesn't know what horror is (“Oh, if only it gave me the creeps!”). Then the princess's maid has an idea: she gives the princess a bucket of cold water with fish. The princess tips that into the sleeping boy's face at night - and then he shudders.

Text history

In contrast to the undemanding fairy tale text of the 1st edition, Wilhelm Grimm's later adaptation also combines legendary and fluctuating motifs under the new heading specifically based on the fairy tale (probably based on Wickram's Rollwagenbüchlin ). Wilhelm Grimm, like many other fairy tales, gradually adorned the text himself with “idioms from the people”. "Shudder" originally means the tingling of the skin, which perhaps better corresponds to the naive physical feeling of a fairy tale hero than "fear". It was only through this fairy tale, which Bechstein took over as Das Schuseln in his German Fairy Tale Book , that it became standard German. Heinz Rölleke mentions other literary receptions: A story by Wilhelm Langewiesch 1842, Hans Christian Andersen 's Little Klaus and Big Klaus (1835), Wilhelm Raabe's The Path to Laughing (1857) and Master Author (1874), Rainer Kirsch's Auszog das Fear zu learn (1978), Günter Wallraffs From one who moved out and learned to be afraid (1979) and adaptations of fairy tales by Ernst Heinrich Meier , Ludwig Bechstein ( The horror , cf. also The courageous flute player ) and Italo Calvino . Wilhelm Grimm seems to have intuitively grasped the inner stringency of the material correctly. AaTh 326 is interpreted today as an independent narrative type which, after unsuccessful attempts to learn fear from a male hero, leads to awareness of death. In less fluctuating degrees, he is often shocked by his changed perspective when his head is cut off. One such version is Flamminio in Straparola (No. 10). Bechstein tells many details differently, the course of the plot remains the same. Bechstein then also uses the word “creeps” in Vom Büblein, who did not want to wash and in Die schlimme Nachtwache .

In the fairy tale there are elements that refer to Lohfelden-Crumbach : The old sexton's house, the church tower with its steep stairs and the streams in which there were once gobies.

Grimm's note

The fairy tale is in the children's and house tales from the 2nd edition from 1819 and before 1818 in the magazine Wünschelruthe (No. 4). It is based on a version “in the Schwalm area ” (by Ferdinand Siebert ), a “Meklenburg narrative” and one “from Zwehrn ” (probably by Dorothea Viehmann ). The version of the 1st edition from 1812 Gut Kegel- und Kartenspiel contained only the episode in the castle. The Brothers Grimm note that the samples vary in detail depending on the source and mention KHM 81 Bruder Lustig , KHM 82 De Spielhansl and Gawan im Parzival for comparison .

The body that the boy wants to warm in bed comes from the Zwehren version. Here he plays against ghosts with nine bones and a skull and loses all money. In a "third Hessian", the master pours cold water over the tailor boy in bed. In a fourth, a young Tyrolean and his father decide to learn to fear. He shaves the beard of a ghost that is completely covered with knives, then it tries to cut its neck and disappears when it strikes twelve. He kills a dragon and takes its tongues as evidence, as in KHM 85 The Gold Children .

A fifth story "from Zwehrn" (probably by Dorothea Viehmann ) they give in detail: The blacksmith's son goes into the world to be afraid. The dead man on the gallows under which he sleeps asks him to report the schoolmaster as a real thief in order to be properly buried. In return, his spirit gives him a staff that beats all ghosts. With this, the blacksmith frees a cursed lock, locks up the black ghosts and the black poodle, as well as the priest because he looks like that. The gold clothes the king gives him as a thank you are too heavy for him, he keeps his old smock. But he is happy about the cannon firing, now that he has seen the fearful me.

In a sixth "aus dem Paderbörnischen" (probably from the von Haxthausen family ) the father sends Hans to get a skull and lets the two daughters play ghosts, but Hans turns their necks. He has to emigrate and calls himself Hans Fürchtemienig. Every night in the haunted castle he is escorted by a soldier who goes to make a fire because of the cold and loses his head. Hans plays cards with a headless man, loses, then wins. The third night a ghost tries to drive him away. You bet who will get their fingers in the keyhole first. The ghost wins and Hans wedges him tight and hits him until the ghost can be spellbound with his own into the flower garden.

You also mention references: Wolfs Hausmärchen p. 328, 408 and Dutch legends p. 517-522; Zingerle pp. 281-290; Prohle 's Children's and Folk Tales No. 33; Molbech Swedish No. 14 Graasappen and Danish No. 29 de modige Svend . Hreidmar learns "in an Icelandic tale" what anger is. You also mention Goethe's statement about the fairy tale.

interpretation

Søren Kierkegaard uses the fairy tale to show how fear in faith can lead to freedom. According to Edzard Storck , the hero in his innocence is not afraid of the constricting, gloomy in his soul. Storck quotes Wolfram von Eschenbach about Parzival : "That God invented Parzivaln, To whom no horror brought terror."

Interpretation by Hedwig von Beit : The cats are preliminary stages of the later ghost: They propose a game, which the spirit itself does in variants, and like it are pinched (cf. KHM 8 , 20 , 91 , 99 , 114 , 161 ). Spirits of the dead appear in animals, skittles in fairy tales often consist of bones and skulls. The realm of the dead aspect of the unconscious comes to the fore when the consciousness behaves negatively towards it - as the naive, actually not courageous son does here in compensation for the behavior of others. Naively, he treats ghosts like real opponents, but does not panic, so that the unconscious conflicts can take shape and be fixed. The woman shows him the part of life that is unconscious to him. In many variations he is shocked by looking backwards or his own backside when his head is placed upside down, which in the interpretation amounts to the sight of death or the afterlife.

Franz Fühmann thinks that the hero obviously feels that he lacks a human dimension. Peter O. Chotjewitz says that he was simply not told the words for feelings, which he now associates with his alleged stupidity. Psychoanalytically oriented specialist literature calls the fairy tale time and again when fear is not experienced. Bruno Bettelheim understands the fairy tale to mean that in order to achieve human happiness, repressions have to be lifted. Even a child is familiar with repressed, unfounded fears that arise in bed at night. Sexual fears are usually felt as a disgust. Also Bert Hellinger says to the fear of devotion to the woman is actually the biggest fear of the man. Wilhelm Salber notices the effort, how fears are demonstratively built up and destroyed with ghosts and the dead in order to avoid proximity to banal life, only sympathy brings movement here. The homeopath Martin Bomhardt compares the fairy tale with the remedy picture of thuja . According to Hans-Jürgen Möller , the text describes, except at the end, the very opposite of an anxiety disorder, the dangerous consequences are not shown. Egon Fabian and Astrid Thome see in the fairy tale the insight into the psychological necessity of perceiving fear, which is otherwise sought outwardly and remains inwardly unattainable as primal fear. Also Jobst Finke understands the behavior of the hero as überkompensatorischen attempt of coping with anxiety.

It is one of the not uncommon stories in which a swineherd, a resigned soldier or prince erring, always someone 'from far away', wins a king's daughter and inherits the father ("gets half the kingdom" or the like) (cf. B. The devil with the three golden hairs ). This is about the story of a matrilineal line of succession in which the daughters and not the sons inherit. If the story moves on to a patrilineal society, a strong explanation was needed there to understand this 'solution' - here the rare gift of never being afraid and an unusually resolute wife.

Receptions and parodies

In Hermann Hesse's tale The Latin Schoolboy , the shy protagonist tries to recite the fairy tale to a group of young girls who already know it. A volume of reports by Günter Wallraff about social grievances is the name of one who moved out and learned to fear . An instructor threatens the recruits: “It will soon be time for you to make me laugh! Once that happens, you will think of me your whole life! ”Parodies like to play with the title and interpret Hans as an insecure person or a capitalist: Gerold Späth's Hans has a worldwide career and forgets that he was looking for the creeps. Rainer Kirsch sketches a film version in which the hero is last murdered by Hofschranzen and so learns to be afraid too late. Even Karl Hoche hero does not find even funny capitalism, only the Emanze. With Janosch, the boy only thinks of skittles and cards, plays night after night with the headless ghost, the princess dies at some point. Günter Grass uses the phrase "How I learned to be afraid" in his autobiography When Skinning the Onion several times for the title and description of the fourth chapter of the war effort, which he apparently survives like in a fairy tale. The title of the fairy tale is often varied, e.g. B. by the band We are Heroes in their song Put on something : "You have undressed to teach us fear ...". The time titled z. B. a travelogue of someone who set out to find peace , an interview on risk research Learning to be afraid. Ruediger Dahlke writes about old age: "The emotional task of this phase of life is fairytale-like and means to move out again - as in youth and puberty - to learn to fear when descending to the dark shadow pole."

In Lohfelden in Vorsterpark, a work of art is dedicated to the fairy tale.

Movie

- 1988: The Fearless ( Nebojosa ), ČSSR, feature film, director: Július Matula , based on Grimm's fairy tale of someone who set out to learn to be afraid in connection with the fairy tale circle about the black princess .

- 1988: The Storyteller , English-American television series, season 1, episode 2: Fearnot .

- 1999: SimsalaGrimm , German cartoon series, season 1, episode 10: Fairy tale of someone who set out to learn to be afraid

- 1982–1987: Shelley Duvall's Faerie Tale Theater (USA 1982–1987) , American television series, broadcast on "Showtime" from 1982 to 1987. Third season: The Boy Who Left Home To Find Out About The Shivers .

- 2014: From someone who set out to learn to be afraid , Germany, fairy tale film of the 7th season from the ARD series Six in one fell swoop , director: Tobias Wiemann

literature

- Brothers Grimm: Children's and Household Tales. Last hand edition with the original notes by the Brothers Grimm. With an appendix of all fairy tales and certificates of origin, not published in all editions, published by Heinz Rölleke. Volume 3: Original Notes, Guarantees of Origin, Afterword. Reclam, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-15-003193-1 , pp. 21-27, pp. 443-444.

- von Beit, Hedwig: Contrast and renewal in fairy tales. Second volume of «Symbolism of Fairy Tales». Second, improved edition, Bern 1956. pp. 519-532. (A. Francke AG, publisher)

- Breitkreuz, Hartmut: Trapping unholder beings. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 3. pp. 1261-1271. Berlin, New York, 1981.

- Heinz Rölleke: Learn to be afraid. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 5. Berlin, New York 1987, pp. 584-593.

- Verena Kast: Paths out of fear and symbiosis. Fairy tales interpreted psychologically. Walter, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-530-42100-6 , pp. 14-36.

Web links

- Learn to fear as mp3 audio book (23:55) ( LibriVox )

- Märchenatlas.de on fairy tales from someone who set out to learn to fear

- Interpretation of Daniela Tax to learn from one who set out to fear

- Illustrations

Individual evidence

- ↑ Heinz Rölleke: Learn to be afraid. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 5. Berlin, New York 1987, pp. 584-593.

- ↑ https://www.lohfelden.de/de/freizeit/sehenswuerdheiten-tourismus/vorsterpark/

- ↑ Ulrich H. Körtner: Weltangst and Weltende. A theological interpretation of apocalyptic. P. 356.

- ↑ Edzard Storck: Old and new creation in the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm. Turm Verlag, Bietigheim 1977, ISBN 3-7999-0177-9 , pp. 417-421.

- ↑ by Beit, Hedwig: Contrast and Renewal in Fairy Tales. Second volume of «Symbolism of Fairy Tales». Second, improved edition, Bern 1956. pp. 519-532. (A. Francke AG, publisher)

- ↑ Franz Fühmann: (The fairy tale of the one who set out to learn the horror). In: Wolfgang Mieder (Ed.): Grim fairy tales. Prose texts from Ilse Aichinger to Martin Walser. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt (Main) 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X , p. 60 (first published in: Franz Fühmann: Twenty-two Days or Half of Life. Hinstorff, Rostock 1973, p. 99.).

- ↑ Peter O. Chotjewitz: From one who went out to learn to fear. In: Wolfgang Mieder (Ed.): Grim fairy tales. Prose texts from Ilse Aichinger to Martin Walser. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt (Main) 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X , pp. 61–63 (first published in: Jochen Jung (Hrsg.): Bilderbogengeschichten. Fairy tales, sagas, adventures. Newly told by authors of our time. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1976, pp. 53-55.).

- ↑ Bruno Bettelheim: Children need fairy tales. 31st edition 2012. dtv, Munich 1980, ISBN 978-3-423-35028-0 , pp. 328-330.

- ↑ Bert Hellinger, Gabriele ten Hövel: Recognize what is. Conversations about entanglement and resolution. 13th edition. Kösel, Munich 1996, ISBN 9-783466-304004, p. 112.

- ^ Wilhelm Salber: fairy tale analysis (= work edition Wilhelm Salber. Volume 12). 2nd Edition. Bouvier, Bonn 1999, ISBN 3-416-02899-6 , pp. 85-87, 140.

- ^ Martin Bomhardt: Symbolic Materia Medica. 3. Edition. Verlag Homeopathie + Symbol, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-9804662-3-X

- ^ Gerhard Köpf, Hans-Jürgen Möller: ICD-10 literary. A reader for psychiatry. German Univ.-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2006, ISBN 3-8350-6035-X , p. 219.

- ↑ Egon Fabian, Astrid Thome: Deficit Anxiety, Aggression and Dissocial Personality Disorder. In: Personality Disorders. Theory and therapy. Volume 1, 2011, ISBN 978-3-7945-2722-9 , pp. 24-34.

- ^ Jobst Finke: Dreams, Fairy Tales, Imaginations. Person-centered psychotherapy and counseling with images and symbols. Reinhardt, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-497-02371-4 , p. 194.

- ^ Hermann Hesse: The Latin student. In: Hermann Hesse. The most beautiful stories. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-518-45638-5 , pp. 70-100.

- ^ Günter Wallraff: From one who moved out and learned to be afraid. 30th edition. Zweiausendeins, Frankfurt am Main 1986, p. 26 (first Weismann, Munich 1970).

- ↑ Gerold Späth: No fairy tale about someone who went out and did not learn to fear. In: Wolfgang Mieder (Ed.): Grim fairy tales. Prose texts from Ilse Aichinger to Martin Walser. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt (Main) 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X , pp. 70-71 (first published in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung. No. 302, December 24/25, 1977, p. 37).

- ↑ : Rainer Kirsch to get undressed to fear. In: Wolfgang Mieder (Ed.): Grim fairy tales. Prose texts from Ilse Aichinger to Martin Walser. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt (Main) 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X , pp. 64–69 (1977; first published in: Rainer Kirsch: Auszog das fear zu Learn. Prosa, Gedichte, Komödie. Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek 1978 , Pp. 187-193.).

- ↑ Karl Hoche: Fairy tale of the little gag, who undressed to learn how to shudder. In: Wolfgang Mieder (Ed.): Grim fairy tales. Prose texts from Ilse Aichinger to Martin Walser. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt (Main) 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X , pp. 72–77 (first published in: Karl Hoche: Das Hoche Lied. Satiren und Parodien. Knaur, Munich 1978, pp. 227–233. ).

- ^ Janosch: Skittles and card game. In: Janosch tells Grimm's fairy tale. Fifty selected fairy tales, retold for today's children. With drawings by Janosch. 8th edition. Beltz and Gelberg, Weinheim and Basel 1983, ISBN 3-407-80213-7 , pp. 176-182.

- ↑ Time. April 10, 2014, No. 16, pp. 67, 77.

- ^ Rüdiger Dahlke: Age as a gift. About the art of keeping your wits about a crazy world. Arkana, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-442-34234-1 , pp. 57–58.