Mushrooms containing psilocybin

|

|

Please note the instructions for collecting mushrooms ! |

Psilocybin- containing mushrooms are a group of psychoactive mushrooms , also known as magic mushrooms or hallucinogenic mushrooms . Mushrooms belonging to this group contain the psychedelic substances psilocybin and psilocin .

Mushrooms containing psilocybin are common worldwide; most are found in the genus of the bald heads . A total of over 180 species are known. The pointed conical bald head ( Psilocybe semilanceata ), which is often found on naturally fertilized pastures, is particularly widespread in Central Europe . Cuban bald heads ( Psilocybe cubensis ) are often offered for sale (legal or illegal) .

Designations

There are different names for mushrooms containing psilocybin from culture to culture, e.g. B. Meat of the gods in parts of America, or foolish mushrooms in Austria. Other names tend to express the type of effect, such as hallucinogenic or psychoactive mushrooms . Western consumers also use terms such as magic mushrooms, psilos, shrooms, paddo etc.

history

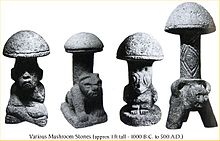

It is believed that mushrooms containing psilocybin and other psychoactive mushrooms were known in many cultures and were mainly used for religious purposes. The first finds that suggest a use date from 1000 to 500 BC. Further evidence of its use can be found in the following centuries from different cultures, occasionally up to the present day. Traditional religious usage is detailed in the article Psychoactive Mushrooms, section Use as Entheogens .

Middle and South America

The shamanic use of psychoactive mushrooms is best known in Latin America . There are so-called mushroom stones that date back to 1000–500 BC. To be dated. The first written evidence of the use of hallucinogenic mushrooms in Western records is the book Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España by Bernardino de Sahagún from the 16th century. It describes in several places the use and effects of what the Aztecs called “ Teonanacatl “(mostly translated as the flesh of God / the gods, holy or divine mushrooms). This is how he describes a celebration of business people:

“At the festive gathering [...] they ate mushrooms. They did not eat any other food; they only drank chocolate all night. They ate the mushrooms with honey. When the mushrooms began to work, there was dancing and crying [...] Some saw in their visions how they died in war [...], some how they became wealthy and could buy slaves [...], some how they committed adultery and how they were then stoned and their skulls smashed in [...], some how they drowned in water [...], some how they found peace in death [...] all of these things they saw. When the mushrooms wore off, they sat together and told each other what they had seen in their visions. "

In later colonial records of the indigenous peoples, the use of mushrooms is mentioned less often. In the eyes of Christian missionaries , the rituals were pagan and should therefore be combated. In particular, the assumption of the Indians that God speaks directly to them through certain plants or here mushrooms stood in contrast to the Christian doctrine of salvation, in which the church proclaims the word of God. For the Christian missionaries the devil spoke from the mushrooms. Because of this, the rituals became more and more secret cults, which is why they were probably not rediscovered in the West until the middle of the 20th century. Some of the species found in Central America are still used in shamanistic rituals. They serve or were used to establish contact with ancestors or gods, were used in healing rituals, and also used for ritual and solemn occasions.

Discovery and Exploration in the West

The existence of psychoactive mushrooms, as described in early testimonies from Central America, was thought by many to be unlikely or a myth. In 1915, for example, the ethnobotanist W. Safford came to the conclusion after some studies that the records of early colonialists were a mistake. He assumed that the dried peyotl cactus was mistaken for a mushroom. On the other hand, the Mexican doctor Blas Pablo Reko , who came from Austria, repeatedly claimed from the 1920s that the mushrooms actually existed, but identified them as fly agarics . Ultimately, it was only R. Gordon Wasson and his wife Valentina who, with the help of the shaman Maria Sabina, succeeded in proving the existence of mushrooms in the middle of the century. After gathering clues from the literature, they decided to look for them in Mexico. In 1953 Wasson was able to observe a mushroom ritual that contained elements of Christian and traditional religion. In 1955 he was able to actively participate in a ceremony together with Allen Richardson and thus convince himself of the effect.

In 1956 he went on another expedition with the French mycologist Roger Heim and participated in a ritual. As a result, Heim collected, cultivated and identified appropriate mushrooms. Between 1953 and 1962 Wasson undertook a total of ten field studies, among others with people like Gastón Guzmán or Albert Hofmann . He finally succeeded in isolating the main active ingredient psilocybin and psilocin in 1958. In the past 20 years, J. Gartz has published most of the work on fungus chemistry in leading botanical journals. Other publicists on mycology and ethnobotany are P. Stamets, J. Ott and G. Samorini with a large number of articles and several books.

Mushroom culture in the west

Psychoactive mushrooms became widely known through a Life article written by Gordon Wasson in 1957 , in which he presented his findings. Similar to LSD, the mushrooms were consumed within alternative social groups, as well as partly in artistic and intellectual circles (see also psychedelic art ). However, they never achieved the meaning of LSD.

From the 1990s onwards, interest in psychoactive mushrooms increased again. This was attributed to the commercial sales in smart shops and also associated with an increasing trend “back to nature” and completely changed sales and information opportunities through the Internet. The smart shops operated in unclear legal areas or gaps left open or tolerated by the legislature. Not only ready-made mushrooms were sold in smart shops, but also material for self-cultivation. The techniques for cultivating mushrooms under simple conditions, which had been developed since the 1960s and were largely driven by experiments with psychoactive mushrooms, were used. So mushrooms were not only collectable in many areas, but also legally or illegally available for sale, as well as the materials and knowledge about their cultivation. While sales were de facto legalized in the Netherlands, a trend began in the 2000s towards a tightening of the legal situation in some European countries, which eventually led to a tightening of Dutch laws again. Nevertheless, there are still legal or semi-legal offers in the EU, which gives mushrooms a special position similar to cannabis, albeit mostly more restrictive. Similar to cannabis, there are also interest groups on the Internet, mostly in the form of information forums, which the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction also uses to gain information.

The consumption of mushrooms has always remained a societal fringe phenomenon, just as the income for most consumers is limited to a few attempts. The largest user group is made up of people with drug experience. Mushrooms containing psilocybin are also consumed for spiritual and self-finding or consciousness-expanding purposes.

Types and distribution

A total of 186 species are known worldwide, 116 of them in the genus Psilocybe (bald heads). Further species can be found in the genera Gymnopilus (flammable) (14), Panaeolus (fertilizer) (13), Copelandia (12), Hypholoma , Inocybe , Pluteus (6 each), Conocybe , Paneolina (4 each), Gerronema (2) , Agrocybe , Galerina and Mycena (1 each).

In late summer and autumn, the conical bald head often grows on naturally fertilized pastures in Germany and neighboring countries . However, Psilocybe cyanescens has spread on wood debris in the last 15 years and is found locally in large numbers, such as B. in Central Germany. Their strong blue discoloration with pressure and with age is characteristic of the fungus and is otherwise only found in the Röhrlingen in Europe, which are not psychoactive. The psychoactive substances psilocybin and psilocin were also detected in the greenish-gray roof mushroom ( Pluteus salicinus ). Psilocybe mushrooms can be confused relatively easily with other species, some of which can cause fatal poisoning (e.g. Galerina marginata , Galerina autumnalis or Galerina venenata ).

Active ingredient concentration

The content of psilocybin and psilocin in mushrooms varies significantly between different species and also within them, across different variations from mushroom to mushroom. The active ingredient content is also distributed differently within the mushrooms. For example, the species Psilocybe samuiensis was found to have the highest concentration in the cap. In general, the psilocybin and psilocin content of dried mushrooms is between 0.1–2% by weight and 0.01–0.2% for fresh mushrooms.

| Surname | Psilocybin [%] | Psilocin [%] | Baeocystin [%] | Total [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conocybe cyanopus | 0.930-0.450 | 0.70-0.00 | 0.030-0.100 | 1.03-0.55 |

| Conocybe smithii | n / A | n / A | 0.40-0.80 | 0.40-0.80 + |

| Gymnopilus purpuratus | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.05 | 0.68 |

| Gymnopilus validipes | 0.12 | - | - | 0.12+ |

Panaeolus cinctulus |

0.150-0.600 | 0.00 | 0.001-0.005 | 0.151-0.605 |

Psilocybe azurescens |

1.78 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 2.51 |

| Psilocybe baeocystis | 0.85 | 0.59 | 0.10 | 1.54 |

Psilocybe bohemica |

0.93-1.34 | 0.11-0.28 | 0.02 | 1.06-1.47 |

Psilocybe cubensis |

0.63 | 0.25-0.60 | 0.02-0.025 | 0.90-1.26 |

Psilocybe cyanescens |

0.85 | 0.36 | 0.03 | 1.24 |

| Psilocybe cyanofibrillosa | 0.21 | 0.04 | n / A | 0.25+ |

| Psilocybe hoogshagenii | 0.60 | 0.10 | n / A | 0.70+ |

| Psilocybe liniformans | 0.16 | n / A | 0.005 | 0.17+ |

Psilocybe semilanceata |

0.98 | 0.02 | 0.36 | 1.36 |

| Psilocybe stuntzii | 0.36 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.5 |

Psilocybe tampanensis |

0.68 | 0.32 | n / A | 1.00+ |

| Psilocybe weilii | 0.61 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.93 |

effect

| amount | effect |

|---|---|

| 3-6 mg | Threshold, slight intoxication |

| 5-10 mg | hallucinogenic, stimulating effect |

| ~ 10 mg | typical consumption dose |

| 10+ mg | enhanced hallucinogenic effects |

| ~ 20 mg | high consumption dose |

| 20+ mg | strong hallucinogenic effects |

| 30+ mg | Maximum dose |

| 20,000 mg | presumed lethal dose |

The effect of the mushrooms is similar to that of LSD , but is of shorter duration. In general, a change in perception and consciousness can be observed. As with many psychedelic drugs , the effects are very individual and can produce a wide variety of effects in different users. The condition of the consumer, the environment ( set and setting ) and the dose are of decisive importance. The effect occurs about 10 to 120 minutes after ingestion, peaks after 1.5-3 hours and lasts about 3-8 hours. In rare cases, the effects can last longer. By changing the perception of time, it can appear longer. The low dose of mushrooms containing psilocybin in the threshold range below or within the effective dose is called microdosing or mini dosing .

pharmacology

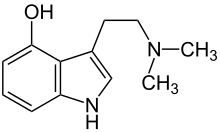

In addition to the mainly active tryptamines psilocybin and psilocin , psilocybin mushrooms often also contain the similar but weaker substances baeocystin and norbaeocystin as well as harmane alkaloids . Psilocin is a hydrolysis product of psilocybin and as such is actually the psychoactive form of psilocybin. In the body, psilocybin is converted into psilocin by splitting off a phosphate group. Both substances are similar to the neurotransmitter serotonin . Psilocin is a partial agonist with a high affinity for the 5-HT 2A receptor (“serotonin receptor”) and is therefore one of the classic hallucinogens. However, like LSD, it does not act on dopamine receptors .

Drug class

There is no consensus as to which term best describes the effects of mushrooms. In general, the active ingredients of the mushrooms are psychoactive or psychotropic , i. H. changing the psyche. Aldous Huxley coined the term hallucinogen with his text The Doors of Perception from 1954 about his experiments with mescaline . Accordingly, the mushrooms are also often defined, which is problematic because real hallucinations rarely occur and pseudo-hallucinations and other changes in vision are only one aspect of the effect that only occurs at moderate doses and in full development only in high doses, while other changes in consciousness are excluded. Mushrooms were used as psychedelic substances after Humphry Osmond or Timothy Leary . H. "The soul-producing" substances are defined. Closely related to this idea, there is also talk of mind-altering substances. Both the term hallucinogen and the term psychedelics have been criticized by ethnopharmacologists , including Gordon Wasson, as being borrowed from psychiatric medicine. Hallucinations are often associated with psychoses and the choice of this term therefore means a misunderstanding of reality. In order to describe traditional intoxicants and their effects, they chose the term " entheogenic ", which meant that the substances would "produce God in oneself". In this definition, the insights, inspirations, and mystical or spiritual experiences that often occur were particularly emphasized.

body

Some often observed effects are increased energy and heartbeat, physical well-being, dilated pupils , relaxation, muscle relaxation, loss of appetite, feeling cold in the extremities, slight dizziness; less often nausea, weakness, chills, muscle pain, abdominal pain. Somatic side effects, which are generally of little importance, can also be caused by the mushroom material itself and not the active ingredient.

perception

Depending on the dose, more or less pronounced changes in the sense of sight, hearing and touch take place as part of a general change in perception . With regard to the sense of sight, an increased perception of colors and contrasts can be observed, as well as increased visual acuity, and lights are perceived as extraordinarily bright. Surfaces appear to be rippling, shimmering, or breathing. Complex visions of objects or images take place with open or closed eyes. Objects warp, transform, or change color. A feeling of merging with the environment can arise. Noises are heard more clearly, music can gain rhythm and depth. Synesthesia is sometimes reported, such as seeing sounds, tasting colors, and the like.

psyche

Since psilocybin has a similar effect to LSD, it can also be assumed that it causes a kind of model psychosis . Psychoses, the effects of hallucinogenic substances and the dream process are associated with similar processes in the brain and show similar patterns in the course and perception of these experiences. A changed perception and sensation of one's own person and the environment occurs. In principle, the effect is very variable; it can provoke both the greatest feelings of happiness and the worst fears. The following are often described as positive effects: euphoria, urge to laugh, creative, philosophical flow of thoughts and ideas, associative loosening , surprising perceptions, everyday things appear fascinating, a deep understanding of things, life-changing, often spiritual experiences. Furthermore, the paradoxical feeling of having a normal and a strongly changed psyche at the same time, of being emotionally sensitive ( entactogen ), of feeling a special connection or unity with other people or the world, of having a changed sense of time and space was described. It can displaced or is, in the unconscious emerge exploiting Dende thoughts or memories. This is often accompanied by experiences or insights that are felt to be profound and life-changing for a short time. At the same time, just by reactivating suppressed memories or sensations, there is also the risk of experiencing a painful experience or feeling during the effect. Fearful derealization and depersonalization processes can occur. Since stimulus processing is influenced, a flood of stimuli can occur, especially with many external stimuli, which has a confusing or frightening effect.

Effective phases, self and external perception

In an early study (1961) with medical professionals as test persons, an attempt was made to divide the effect into different phases. Both externally observable changes and subjective perceptions were recorded.

An inward turn was defined as the first phase , which occurred about 15-25 minutes after ingestion and showed only minor external signs. For example, a reduction in the typical attitude towards conversation partners, namely leaning forward, was found. There was a decrease in facial expressions and gestures, the voice became quieter, more melodic, the pitch rose; a heaped sigh was noted. In this phase , the test subjects described a changed physical experience that was perceived as strange, strange or even frightening.

The second phase was defined as an outward turn , which occurred about 30-60 minutes after ingestion. More lively movements and more frequent changes of posture were noted. There was an increase in facial expressions and gestures, and there were no signs of clouding of consciousness. A fascination with objects in the immediate vicinity was heard, and only limited attention to interlocutors. Laughter was also often reported. The speaking voice was changed as before, sentences were often not finished. The test subjects described a change in their visual experience. They perceived their surroundings in an affective, aesthetic way and related to their own experience. The space outside of the fascinating experience became increasingly insignificant.

As a third phase which was submersion defined, which occurred about 90-120 minutes after ingestion, but mg only at higher doses of approximately 10, or 0.15 mg per kg body weight. A decrease in motor skills compared to the previous phase up to more frequent immobility and a generally more slack posture was found. There was also a decrease in facial expressions, often a stare, but no signs of clouding of consciousness. A further decline in the need to speak was recorded. At the same time there was a radical change in the speaking voice. It was characterized by a (very) low volume, a reduction in dynamics, pitch and melody, and could also be described as monotonous and without accent. Internally, some test subjects found that they were absorbed inward, others found that they were absorbed outward, with the focus on the fascination of external perceptions. It was difficult for the test subjects to provide information about the condition and experience during this phase. They seemed to them immediately in words. In general, there were processes of derealization and depersonalization .

Localization of the effect in the brain

Today there is a consensus that the effect of the psychoactive substance psilocin secondary, as with other psychedelic substances , particularly over the serotonin - receptor type 5-HT 2A is triggered.

Neural excitation via this receptor in turn leads to an increase in GABA -mediated, inhibitory signals in important switching centers in the brain. Investigations of the visible effects of psilocin in the brain by means of imaging methods have shown several important centers with reduced activity. The stronger the effect of psilocin experienced by the test subjects, the more the neuronal activity of these centers was reduced. In contrast, to the surprise of the researchers, no brain regions with increased activity were found. A possible explanation has been suggested that psilocin disrupts the normal balance of neural information flows.

hazards

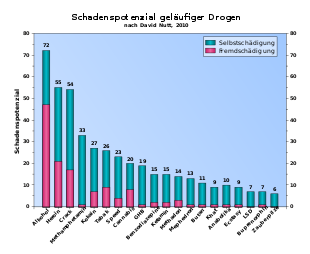

In a 2010 classification study on the harmfulness of drugs to the individual and the environment from Great Britain, psychoactive mushrooms were classified as the least harmful of the drugs examined. The non-addiction-inducing effect and the low toxicity of the active ingredients are decisive factors. The main dangers of consuming mushrooms are mental health risks, accidents and mistaking them for other mushrooms. Risk assessments from 2000 and 2007 by the Coordination Center for the Assessment and Monitoring of new drugs (CAM) for the Dutch Ministry of Health and a review from 2011 come to similar assessments. The CAM reports concluded that the mushrooms' physical and psychological addiction potential was low. The acute toxicity is moderate and the chronic toxicity is low. The combined use of mushrooms and alcohol and the mental attitude with which the magic mushrooms would be used, but deserved attention.

Dependence potential and somatic risks

Mushrooms do not cause physical or psychological dependence or withdrawal symptoms. Their active ingredients are therefore regarded as non-addictive substances. The consciousness researcher Ronald Siegel described in 1981, as an expert of the WHO, that consumers took the mushrooms on average a maximum of ten times, and this at intervals of several weeks. When mushrooms are consumed for several days in a row, a tolerance develops , but this disappears again after a few days.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention rate psilocybin as less toxic than acetylsalicylic acid . The assumed lethal dose exceeds an average consumption dose by 2000 times. It is commonly believed that fatal drug overdose with psilocybin-containing mushrooms is nearly impossible due to the amount of mushroom material to be consumed alone. There are no known causes of organ damage.

In combination with antidepressants from the group of MAO inhibitors , there is an interaction that includes the aspects of strengthening and lengthening.

Psychological risks and accidents

Anxiety disorders and panic attacks can occur (so-called " horror trip ", sometimes longer lasting, hallucinogen persisting perception disorder ). Basically there is the risk of activating a latent psychosis . Medical treatment, among other things, is indicated if the patient is very excited. "Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics" suggests 20 mg diazepam orally . Soothing conversations have been shown to be effective and are therefore an appropriate first step. Antipsychotics can enhance the experience and are therefore contraindicated.

The changed perception of the environment can result in risks for the consumer and the environment during the psilocybin effect, for example the incorrect assessment of the dangers when crossing roads with heavy traffic or when driving a vehicle.

The experience of a bad trip , i.e. a negatively perceived intoxication experience, depends on the one hand on the basic expectations of consumption and the subjective evaluation of an experience, on the other hand with the environment and the dosage. The frequency, strength, type and content of negative sensations are just as individual and different as the effects of mushrooms in general. Like the effect in general, negative sensations are largely determined by the condition of the consumer, the environment ( set and setting ) and the dosage. Acute states of confusion, anxiety and panic are particularly likely with poor starting factors, such as a threatening environment, psychological problems, lack of knowledge or high doses. However, they do not lead to long-term psychological impairments for most users and disappear as the effects wear off. A bad trip can also be the trigger or the first appearance of a latent psychosis.

There is no reliable information about the frequency of bad trips or horror trips, which, in addition to a few studies, is also connected with the fundamental problem of a highly subjective effect of the substance and the subjective evaluation of an experience. There are different studies and surveys that allow a rough assessment. In a study of the frequency of bad trips between the popularization of psychedelic substances in the early 1960s to 1975, a steady decline was observed. While around 50% of respondents reported bad trips in the first few years, this number dropped to around 30% by 1975. This was traced back to the knowledge produced in consumer cultures concerning the use of psychedelic substances.

The British music magazine Mixmag carried out a survey in 2005 in which around a quarter of the participating mushroom consumers stated that they had experienced a panic attack in the previous year. Nevertheless, in a later survey by the magazine, 21% of all respondents said they had been treated for mental health problems. At the same time, most of the respondents were users of many other psychoactive substances, which is why it is only possible to draw conclusions about the mushrooms under these circumstances to a limited extent.

In a 2006 study in which 36 test subjects were given a high dose of psilocybin (30 mg / 70 kg) to investigate spiritual experiences more closely, eleven test subjects reported significant fears during one phase of the effect and four of fears during one considerable period of time, and four others saw the experience dominated by fear. At the same time, 67% of the test subjects classified the intoxication after two months as one of the five most significant experiences in life, and 71% as one of the five most spiritually significant experiences in life.

Fungal mix-up

There is a risk of confusing hallucinogenic mushrooms with poison mushrooms. In the years after 1980 and especially after 1995, several mistakes have occurred in central and southern Germany, where especially Psilocybe cyanescens grew spontaneously in the garden on wood residues and for both the honey fungus and for the Kulturträuschling was held.

Consumers

Within Europe, depending on the country, around 0–8% of 15 to 24 year olds have consumed psychoactive mushrooms at least once in their life, mostly in the Netherlands and the Czech Republic as well as Great Britain and Germany, and least in Lithuania, Hungary, France and Germany Poland. Consumption in the last year is 0–5%, consumption in the last month is 0–1.5%. Statistically speaking, the first consumption often takes place in the 18th or 19th year of life. People who have also used other hallucinogens, ecstasy, amphetamines or cocaine have a particular tendency to consume mushrooms. The consumption rate of mushrooms among people from the clubbing scene is higher than the average. It is believed that there are more male users than female users.

Most consumers see mushroom consumption as an experiment and stop using mushrooms after a few attempts. The effect or the intoxication is often perceived as a strenuous, ambivalent experience, a positive or pleasant mood change, as is usual with drugs, is not always given here.

Medical use

From the mid-1950s, when mushrooms containing psilocybin were scientifically developed in the West, to extensive control at the end of the 1960s, studies and therapies with psilocybin or LSD were carried out, especially in the psychiatric field. On the one hand, it was hoped for a better understanding of psychotic behavior: The material was used to induce so-called model psychoses in order to be able to better understand the processes during a psychosis. On the other hand, it was hoped that this would enable the psychiatrist to better empathize with people with psychoses. Since the substances could possibly also reveal repressed feelings and thoughts and make them workable, they were also used in psychotherapy. This has often been referred to as psycholytic therapy . Attempts have been made to treat alcoholics with initial positive results . From the mid-1980s, isolated studies and therapies with hallucinogens were approved again, mostly with patients who did not respond to other treatment methods. Therapies were given to end-stage cancer patients in order to enable them to possibly better deal with death. Studies looked at the effects of psilocybin on depression , migraines, and cluster headaches . In October 2018, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) awarded Breakthrough Therapy status to a large study of psilocybin in the treatment of treatment-resistant depression . In November 2019, the FDA granted Breakthrough Therapy status to the Usona Institute's psilocybin program for the treatment of clinical depression.

Legal position

While some states began to ban hallucinogenic substances, which were becoming more popular in the West, in the 1960s, the substances were still unknown to international law. It was not until the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances came into force in 1971 that the active substances psilocybin and psilocin were declared controlled substances in the west and large parts of the world. The legal status of the mushrooms themselves, however, has been and is interpreted differently. One of the reasons for this is that the mushrooms are geographically widespread and grow naturally.

In some countries hallucinogenic mushrooms (either specific species, or more generally all psilocybin-containing species) are explicitly mentioned as a controlled substance, in others the mushrooms are simply viewed as a carrier for the active ingredients. In some cases, cultivation and possession are only prohibited if they are improperly used to produce controlled substances. Some countries determined the legality according to whether the mushrooms were processed in any way, dried, etc. In some cases the mushrooms fall under general laws that generally prohibit the processing of organisms for the production of psychoactive substances. The way in which spores are controlled is also handled differently in many countries. In some countries, the case law remains unclear as there are too few cases of the application of the law. The European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction provides a rough overview of the (likely) legal status of hallucinogenic mushrooms in the EU.

In the 2000s, the legal situation was clarified or tightened in some EU countries.

In May 2019, a referendum in the US city of Denver voted for the decriminalization of mushrooms containing psilocybin. In June 2019, Oakland became the second US city to decriminalize psilocybin-containing mushrooms.

Germany

In Germany, the active ingredients psilocybin and psilocin (but not the mushrooms explicitly) are listed as non-marketable narcotics in Appendix I of the Narcotics Act (BtMG). Possession and trade in mushrooms containing psilocybin can therefore be interpreted as possession or trade in narcotics (with very limited exceptions, for example for the purpose of mushroom collections) and is therefore punishable in Germany.

According to a ruling by the Higher Regional Court of Koblenz on March 15, 2006, mushrooms were not included in the old version of the BtMG, since at that time only the possession of "plants" and "plant parts" was punishable, but according to the more recent opinion, mushrooms were not part of the Reich of plants belong. With judgment of October 25, 2006, the Federal Court of Justice under Az. 1 Str 384/06 overturned the appeal judgment of the Koblenz Higher Regional Court. On July 23, 2009, the old list was supplemented by the term “mushrooms” (amendment to Section 2 BtMG).

Netherlands

Since December 1st, 2008 a. The sale and possession of psychoactive mushrooms is prohibited in the Netherlands. The spokesman for the Ministry of Justice cited the unknown psilocybin content and the resulting incalculable effects as the reason for the change in the law. The prohibited types of mushrooms are part of the second list of the Opiumwet (Dutch Opium Act), which also includes intoxicants such as hashish . The Openbaar Ministry (Dutch Public Prosecutor's Office ) announced that possession of up to 0.5 grams of dried mushrooms or 5 grams of fresh mushrooms will not lead to criminal prosecution. The ban will affect mushrooms containing psilocybin, while truffles containing psilocybin and mushroom growing kits can be sold. On September 13, 2019, the tax authorities of the Netherlands published the customs categorization and the associated tax rate for magic truffles, thereby legalizing them as luxury goods.

literature

- A. Cerletti: Teonanacatl and Psilocybin . German Medical Weekly. No. 52, December 25, 1959. pp. 2317-2321.

- Jochen Gartz (Ed.): Hallucinogens in historical writings. An anthology from 1913–1968 . Nachtschatten-Verlag, Solothurn 1999, ISBN 3-907080-48-3 .

- Rudolf Gelpke : From journeys into the space of the soul. Reports of self-experiments with delyside (LSD) and psilocybin (CY) . Antaios 1962.

- F. Gnirss: Fear in the provoked border situation , 1967.

- RR Griffiths, WA Richards, U. McCann, R. Jesse: Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance (PDF; 440 kB). In: Psychopharmacology (2006) No. 187. pp. 268-283. Editorial and commentaries (PDF; 268 kB), pp. 284–292.

- RR Griffiths, WA Richards, U. McCann, R. Jesse: Mystical-type experiences occasioned by psilocybin mediate the attribution of personal meaning and spiritual significance 14 months later (PDF; 628 kB). In: Journal of Psychopharmacology 2008, pp. 621-632.

- H. Heimann: Expression phenomenology of model psychoses (psilocybin): comparison with self-portrayal and mental loss of performance. In: Psychiatria et Neurologia 1961.

- Albert Hofmann : The psychotropic ingredients of Mexican magic mushrooms. Basel 1960.

- J. Hillebrand, D. Olszewski, R. Sedefov: “Hallucinogenic Mushrooms: An Emerging Trend Case Study” (PDF; 1.0 MB) European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction , Lisbon 2006, ISBN 92-9168-249-7 .

- MW Johnson, WA Richards, RR Griffiths: Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety. (PDF; 234 kB) In: Journal of Psychopharmacology 2008.

- Christian Rätsch , Roger Liggenstorfer (Ed.): Maria Sabina. The messenger of the sacred mushrooms. From traditional shamanism to worldwide mushroom culture. License issue. AT-Verlag, Aarau 1998, ISBN 3-85502-627-0 .

- Christian Rätsch: Mushrooms and people: Use, effect and importance of mushrooms in culture , AT-Verlag, Aarau 2010, ISBN 9783038005421 .

- M. Sercl, J. Lovarik, O. Jaros: Clinical experiences with psilocybin . In: Psychiatria et Neurologia . 1961.

- Paul Stamets: Psilocybin Mushrooms of the World. A Practical Guide to Safe Identification. With a foreword by Andrew Weil. AT-Verlag, Aarau 1999, ISBN 3-85502-607-6 .

- R. Verres (Ed.): Therapy with psychoactive substances. Practice and criticism of psychotherapy with LSD, psilocybin and MDMA. Huber, Bern 2008, ISBN 3-456-84606-1 .

Web links

- Hallucinogenic mushrooms , information from the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction .

- Psilocybin Mushrooms , Erowid .

- scobel - drugs as medicine. From the illegal drug to the remedy: Will psychedelic substances such as LSD or "magic mushrooms" soon be used as medicines for depression, anxiety disorders and pain? 3sat / ZDF. 2019 (58 min).

Individual evidence

- ↑ G. Guzmán, JW Allen, J. Gartz: A Worldwide Geographical Distribution of the Neurotropic Fungi, An Analysis and Discussion. In: Annali dei Museo civico di Roverto. Italy, 2000, volume 14.

- ↑ "There are small mushrooms in this country called Teonanacatl, [...] whoever eats them experiences visions"; quoted from: A. Cerletti: Teonanacatl and Psilocybin. In: Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift , No. 52, of December 25, 1959, p. 2317.

- ↑ Compare, for example, Albert Hofmann: The psychotropic active ingredients of Mexican magic mushrooms . Basel 1960; Wasson: Seeking the magic mushroom. In: Life magazine, June 10, 1957.

- ^ Wasson's First Voyage. The Rediscovery of Entheogenic Mushrooms. In: John Allen: Mushroom Pioneers. 2002.

- ↑ a b Hallucinogenic mushrooms. EMCDDA, Lisbon June 2006. p. 6.

- ↑ a b Hallucinogenic mushrooms. EMCDDA, Lisbon June 2006. p. 4.

- ↑ a b c Hallucinogenic Mushrooms: An Emerging Trend Case Study. European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction PDF file , Lisbon, June 2006.

- ↑ G. Guzmán, JW Allen, J. Gartz: World Wide Distribution of Magic Mushrooms. In: Annali del Museo civico di Rovereto Volume 14, 1998, pp. 198–280 (PDF file; 1.9 MB).

- ↑ A. Gminder, T. Böhning: Kosmos Naturführer: Pilze. Franckh Kosmos Verlag, ISBN 3-440-10797-3 .

- ↑ J. Gartz, JW Allen, MD Merlin: Ethnomycology, biochemistry, and cultivation of Psilocybe samuiensis Guzmán, Bandala and Allen, a new psychoactive fungus from Koh Samui, Thailand. In: Journal of ethnopharmacology. Volume 43, Number 2, July 1994, pp. 73-80, ISSN 0378-8741 . PMID 7967658 .

- ↑ Dosage Chart for Psychedelic Mushrooms (shtml) Erowid. 2006. Accessed December 1, 2006.

- ↑ Approximate Alkaloid Content of selected Psilocybe mushrooms . www.erowid.org. March 27, 2009. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- ↑ a b c d e f g The Psilocybe Mushroom FAQ, Version 1.2 . sporelab.com. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Dr. Gartz Series Extraction (tacethno.com) . Retrieved February 23, 2011.

- ^ Paul Stamets: Psilocybin Mushrooms of the World. Ten Speed Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0-89815-839-7 , p. 183 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ^ Erowid and contributors: Effects of Psilocybin Mushrooms (shtml) Erowid. 2006. Accessed December 1, 2006.

- ^ Psychedelic Effects of Magic Mushrooms . The Good Drugs Guide. Retrieved December 1, 2006.

- ↑ Kim PC Kuypers, Livia Ng, David Erritzoe, Gitte M Knudsen, Charles D Nichols, David E Nichols, Luca Pani, Anaïs Soula, David Nutt: Microdosing psychedelics: More questions than answers? An overview and suggestions for future research. In: Journal of Psychopharmacology. 33, 2019, p. 1039, doi : 10.1177 / 0269881119857204 .

- ↑ Felix Blei, Sebastian Dörner, Janis Fricke, Florian Baldeweg, Felix Trottmann: Simultaneous Production of Psilocybin and a Cocktail of β-Carboline Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors in “Magic” Mushrooms . In: Chemistry - A European Journal . n / a, n / a, ISSN 1521-3765 , doi : 10.1002 / chem . 201904363 .

- ↑ David E. Nichols (2004): Hallucinogens. In: Pharmacol Ther . 101: 131-181, PDF .

- ↑ Hallucinogenic mushrooms. EMCDDA, Lisbon June 2006, p. 7.

- ↑ CA Ruck, J. Bigwood, D. Staples, J. Ott, RG Wasson: Entheogens. In: Journal of psychedelic drugs. Volume 11, Numbers 1-2, 1979, ISSN 0022-393X , pp. 145-146, PMID 522165 .

- ↑ a b Compare, for example, hallucinogenic mushrooms. EMCDDA, Lisbon June 2006. p. 21; Erowid and contributors: Effects of Psilocybin Mushrooms (shtml) Erowid. 2006. Accessed December 1, 2006.

- ↑ Compare, for example, hallucinogenic mushrooms. EMCDDA, Lisbon June 2006, p. 21 .; Albert Hofmann: The psychotropic ingredients of Mexican magic mushrooms. Basel 1960, pp. 254f .; H. Heimann: Expression phenomenology of model psychoses (psilocybin): comparison with self-portrayal and mental loss of performance. Psychiatria et Neurologia 1961 .; Erowid and contributors: Effects of Psilocybin Mushrooms (shtml) Erowid. 2006. Accessed December 1, 2006 .; The Good Drugs Guide: Psychedelic Effects of Magic Mushrooms . The Good Drugs Guide. Retrieved December 1, 2006.

- ↑ H. Heimann: Expression phenomenology of model psychoses (psilocybin): comparison with self-portrayal and mental loss of performance. In: Psychiatria et Neurologia 1961, pp. 75-89.

- ^ DE Nichols: Hallucinogens. In: Pharmacol Ther. Volume 101, 2004, pp. 131-181, PMID 14761703 (review).

- ↑ RL Carhart-Harris, D. Erritzoe u. a .: Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . Volume 109, number 6, February 2012, ISSN 1091-6490 , pp. 2138-2143, doi: 10.1073 / pnas.1119598109 , PMID 22308440 , PMC 3277566 (free full text).

- ↑ David J Nutt, Leslie A King, Lawrence D Phillips: Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. In: The Lancet. 376, 2010, pp. 1558-1565, doi: 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (10) 61462-6 .

- ↑ Drug Toxicity. Rober Gable, accessed December 14, 2015 .

- ↑ RS Gable: Acute toxicity of drugs versus regulatory status. In: JM Fish (Ed.): Drugs and Society: US Public Policy. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, MD 2006, pp. 149-162.

- ↑ a b c d e Jan van Amsterdam, Antoon Opperhuizen, Wim van den Brink: Harm potential of magic mushroom use: A review. In: Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 59, 2011, p. 423, doi : 10.1016 / j.yrtph.2011.01.006 .

- ↑ The Lancet - press release - alcohol is the nicest… In: Wissenschaft-online.de. November 5, 2010, accessed February 18, 2015 .

- ^ DJ Nutt, LA King, LD Phillips: Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. In: Lancet. Volume 376, Number 9752, November 2010, ISSN 1474-547X , pp. 1558-1565, doi : 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (10) 61462-6 , PMID 21036393 .

- ↑ CAM., 2000. Risk Assessment report relating to paddos (psilocin and psilocybin). Coordination Center for the Assessment and Monitoring of New Drugs (CAM) / Coordinatiepunt Assessment en Monitoring nieuwe drugs (CAM) p / a Inspection des Gesundheitsamt (IGZ) -CAM, The Hague (study on the legal classification and the dangers of psychoactive fungi). (PDF)

- ↑ CAM. 2007. Report of Coordination point Assessment and Monitoring new drugs (CAM). Aanvullende informatie paddoincident in Amsterdam.

- ↑ Jochen Gartz: Fool's Sponges - Psychotropic Mushrooms in Europe. Nachtschatten-Verlag, Solothurn 1999.

- ↑ Magic Mushrooms - Frequently Asked Questions . The Good Drugs Guide. Retrieved January 4, 2007.

- ↑ "Severe agitation may respond to diazepam (20 mg orally). “Talking down” by reassurance is also effective and is the management of first choice. Antipsychotic medications may intensify the experience and thus are not indicated. "Laurence Brunton, Bruce A. Chabner, Bjorn Knollman: Goodman and Gilman's Manual of Pharmacology and Therapeutics . 12th edition. McGraw-Hill, 2011, ISBN 978-0-07-176939-6 , p. 1537.

- ^ Richard Bunce: Social and political sources of drug effects: The case of bad trips on psychedelics. ( Memento of October 20, 2002 in the Internet Archive ) In: E. Zinberg, WM Harding (Ed.): Control Over Intoxicant Use: Pharmacological, Psychological, and Social Considerations. Human Sciences Press. 1982, pp. 105-125.

- ↑ See Hallucinogenic mushrooms. EMCDDA, Lisbon June 2006, p. 22 .; mixmag drugs survey 2010 ( Memento from December 12, 2010 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ RR Griffiths, WA Richards et al. a .: Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. ( Memento of December 17, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) In: Psychopharmacology. Volume 187, Number 3, August 2006, ISSN 0033-3158 , pp. 268-283, doi: 10.1007 / s00213-006-0457-5 , PMID 16826400 .

- ↑ a b c D. E. Nichols: Psychedelics. In: Pharmacological reviews. Volume 68, number 2, April 2016, pp. 264–355, doi : 10.1124 / pr.115.011478 , PMID 26841800 , PMC 4813425 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ a b R. G. dos Santos, FL Osorio u. a .: Antidepressive, anxiolytic, and antiaddictive effects of ayahuasca, psilocybin and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD): a systematic review of clinical trials published in the last 25 years. In: Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 6, 2016, p. 193, doi : 10.1177 / 2045125316638008 .

- ↑ MC Mithoefer, CS Grob, TD Brewerton: Novel psychopharmacological therapies for psychiatric disorders: psilocybin and MDMA. In: The lancet. Psychiatry. Volume 3, number 5, May 2016, pp. 481-488, doi : 10.1016 / S2215-0366 (15) 00576-3 , PMID 27067625 (review).

- ^ Pahnke WN: The psychedelic mystical experience in the human encounter with death. Harv Theol Rev 1969; 62 (1) 1-21

- ↑ CS Grob, AL Danforth, GS Chopra, M. Hagerty, CR McKay, AL Halberstadt, GR Greer: Pilot study of psilocybin treatment for anxiety in patients with advanced-stage cancer. In: Archives of general psychiatry. Volume 68, number 1, January 2011, pp. 71-78, doi : 10.1001 / archgenpsychiatry.2010.116 , PMID 20819978 .

- ^ D. Baumeister, G. Barnes, G. Giaroli, D. Tracy: Classical hallucinogens as antidepressants? A review of pharmacodynamics and putative clinical roles. In: Therapeutic advances in psychopharmacology. Volume 4, number 4, August 2014, pp. 156-169, doi : 10.1177 / 2045125314527985 , PMID 25083275 , PMC 4104707 (free full text) (review).

- ^ S. Patra: Return of the psychedelics: Psilocybin for treatment resistant depression. In: Asian journal of psychiatry. Volume 24, December 2016, pp. 51-52, doi : 10.1016 / j.ajp.2016.08.010 , PMID 27931907 (review).

- ↑ RL Carhart-Harris, M. Bolstridge, J. Rucker, CM Day, D. Erritzoe, M. Kaelen, M. Bloomfield, JA Rickard, B. Forbes, A. Feilding, D. Taylor, S. Pilling, VH Curran , DJ Nutt: Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study. In: The lancet. Psychiatry. Volume 3, Number 7, July 2016, pp. 619-627, doi : 10.1016 / S2215-0366 (16) 30065-7 , PMID 27210031 .

- ^ JJ Rucker, LA Jelen, S. Flynn, KD Frowde, AH Young: Psychedelics in the treatment of unipolar mood disorders: a systematic review. In: Journal of psychopharmacology. Volume 30, Number 12, December 2016, pp. 1220-1229, doi : 10.1177 / 0269881116679368 , PMID 27856684 (review).

- ↑ Deutscher Ärzteverlag GmbH, editor of the Deutsches Ärzteblatt: Cancer: Fungal hallucinogen relieves depression and takes away fear of ... ( aerzteblatt.de [accessed on September 22, 2018]).

- ↑ COMPASS Pathways Receives FDA Breakthrough Therapy Designation for Psilocybin Therapy for Treatment-Resistant Depression - COMPASS. Retrieved December 6, 2018 (American English).

- ↑ Psilocybin against depression • ARZNEI-NEWS. Retrieved November 25, 2019 .

- ↑ Hallucinogenic mushrooms. EMCDDA Lisbon June 2006, p. 23.

- ↑ Overview of the (probable) legal status of hallucinogenic mushrooms in the EU

- ↑ Michaela Haas: Psilocybin Mushrooms: Legalization of Magic Mushrooms in Denver. Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin, May 10, 2019, accessed on May 29, 2019 .

- ↑ Tom Angell: Denver Voters Approve Measure To Decriminalize Psychedelic Mushrooms. Forbes, accessed May 29, 2019 .

- ↑ Colleen Shalby: Oakland becomes 2nd US city to decriminalize magic mushrooms. Retrieved June 5, 2019 .

- ↑ OLG Koblenz, judgment of March 15, 2006, Az. 1 Ss 341/05.

- ↑ Netherlands - Government bans magic mushrooms. In: sueddeutsche.de . May 17, 2010, accessed February 18, 2015 .

- ↑ Wet- en regulgeving: Opiumwet. In: Overheid.nl , accessed on December 2, 2008.

- ↑ Paddoverbod van crashes ( Memento of 2 October 2011 at the Internet Archive ). Openbaar Ministry, accessed December 2, 2008.

- ↑ Toelichting btw-tarief na varsh. In: www.habeningdienst.nl. Retrieved July 26, 2020 (Dutch).