Altered state of consciousness

Altered state of consciousness (abbreviated VBZ, also exceptional state of consciousness or expanded state of consciousness , Eng. Altered state of consciousness , ASC, sometimes altered conscious waking state , VWB) denotes a fixed according to various criteria modulation of consciousness . The term, as it is used today, was coined by the psychiatrist Arnold M. Ludwig in 1966 after he had created an extensive overview of known changes in consciousness. The American psychologist Charles Tart has also contributed significantly to the popularity of the term. Just as there is no generally accepted definition of consciousness today, there is no general definition of altered states of consciousness. The models from the fields of psychology, philosophy and anthropology , which were mainly followed up to the middle of the 20th century, are now supplemented by models from neurochemistry and neurophysiology . In addition, changed states of consciousness are important in almost all cultures and religions. They are also used specifically in psychotherapeutic treatments.

Concept and delimitation

Just as there is no generally accepted, sustainable model for altered states of consciousness, just as there is for the phenomenon of consciousness. This deficiency is also due to the multiple meanings and uses of the term “awareness”. The specialty in the exploration of consciousness lies in the possibility of pursuing two opposing research methods. Since the neural structures and functions are a prerequisite for consciousness, the scientific methods, especially the neuroscientific research approaches, are the one approach. Since psychological and social aspects and functions are also an essential part of the consideration of consciousness and thus psychological and sociological methods are applied, this approach is also called more generally the “third-person perspective”. The other approach is subjective experience, the so-called first-person perspective , which is always used to delimit and describe states. This subjective research approach is based on so-called introspection and is therefore part of one of the most important problems in the current philosophy of consciousness, epistemic asymmetry . The problem with this first-person perspective is that it is random. It is also considered to be epistemologically unsound. The comparison and interaction of these two fundamentally different methods are, however, more essential for researching states of consciousness and for gaining knowledge than in any other field of science.

In the discussion about altered consciousness it also becomes clear that there is no general consensus on what exactly is meant by consciousness . So the term is used in many ways. Consciousness can be understood, for example, as a cognitive function such as attention or as a phenomenological concept in the sense of subjective experience. While the question of consciousness itself was mainly asked in psychology and philosophy , doctors and psychiatrists , on the other hand, were mostly concerned with the question of certain states and disorders of consciousness.

A VBZ is usually differentiated from a pure modulation of the I experience, in which various cognitive functions such as memory or perception are no longer integrated into a self-image as usual. Likewise, altered states of consciousness are not mental simulations like a thought experiment . Distinctions between the psychiatric area of reduced consciousness and impaired consciousness are not made generally and are often discussed.

Since changed states of consciousness not only manifest themselves in front of a cultural, religious and historical context, but also shape it, any attempt at modeling is difficult. Research into altered states of consciousness is also seen as an opportunity to better understand the genesis, maintenance and development of consciousness in general.

Definitions and their difficulties

A definition of states of consciousness that is still widely used today comes from Charles Tart . He is based on Arnold M. Ludwig, who in 1966 took the subjective changes in experience relative to a “normal consciousness” as a yardstick for changed contents of consciousness. Tart defines a changed state of consciousness through a clear qualitative change in the pattern of mental processing or the type of mental functions. In doing so, on the one hand, he distinguishes them from mere changes in feelings and other contents of consciousness. On the other hand, this definition focuses on subjective experience and has no direct reference to empirical measurements or behavioral observations. Nevertheless, changed states of consciousness according to Tart can also be accompanied by a number of subjectively and objectively changed parameters.

G. William Farthing varies this definition only slightly in 1992:

"An altered state of consciousness is a temporary change in the overall pattern of subjective experience such that the individual believes that his psychological functions are markedly different from certain general norms of his normal waking consciousness."

In order to separate the broad spectrum of possible experiences in "normal" waking consciousness from altered states of consciousness, Tart (1969) and Farthing (1992) therefore define ASCs on the basis of six criteria:

- ASCs are not just changes in the contents of consciousness.

- ASCs are characterized by a changed “scheme of experience”, not just in terms of changing individual aspects or dimensions.

- ASCs don't necessarily need to be noticed immediately; their occurrence can also only be determined later.

- ASCs are relatively short-term and reversible.

- ASCs are described and identified based on the differences to everyday consciousness.

- ASCs are ultimately defined by subjective experience and not by behavior or physiological measurements.

The idea of a “normal consciousness” to distinguish it from VBZs is however also criticized. Current theories present consciousness as a process that cannot be understood as a stable, “normal” state . Charles Tart himself argues similarly, who sees everyday consciousness as a useful tool in a complex system of constant change. So a “normal consciousness” would only be a useful construction to talk about change in a meaningful way. For Dieter Vaitl, the experience of “normal psychological functions in the waking consciousness” is only suitable to a limited extent as a benchmark for psychological and neurobiological models of states of consciousness; it is also unclear how normality is defined.

Charles Tart also differentiates between an "altered state of consciousness" and an "identity state of consciousness". An "altered state" is defined via a different subjective experience, an "identity state" being defined via a significant difference between various parameters and other states. These parameters are defined in Tart's conception of his system-theoretical model.

In a more naturalistic, information-processing approach, consciousness and its functions are understood as a representation of the world. Associated with this is a mental separation of the current contents of consciousness from a more fundamental neural, information-processing mechanism. There are also definitions for VBZs in this presentation. Normal waking consciousness is a state in which the known representations of the environment and of the self provide accurate and reliable information. A change in the state of consciousness therefore comes about through a misrepresentation of the content of consciousness. The “normal” representation of the world is lost and the “state” is a state of conscious representation . An advantage of this definition is the possibility of looking for signs of changed mechanisms in physiological and neurological empirical data. Temporary and global changes in the condition can also be distinguished from permanent, neuronally limited mental illnesses. António Damásio defines a proto-self as the representation that creates the maintenance of basic body functions ( homeostasis ) as a result of the involvement of brain areas such as the brain stem in consciousness. The changes in this “status model” of the body in the brain could then cause a change in the state of consciousness.

States of scientific interest

Stanley Krippner distinguishes twenty conditions of closer interest:

- Sleep, dream sleep, life asleep (hypnagogia), waking life (hypnopompic state), hypervigilance (hyperalertness) , lethargy , ecstasy (rapture) , hysteria , dissociation (fragmentation) , "regression", meditative states, trance states (reverie) , daydreams, " inner perception ” (internal scanning) , stupor , coma , memory access (stored memory) ,“ expanded ”consciousness and“ normal ”waking consciousness.

Change of consciousness

definition

Change in consciousness is the process of placing the consciousness into an altered state of consciousness. The term expansion of consciousness is often used synonymously, even if the use of this term seems to ignore restrictive changes in consciousness. Some methods of changing consciousness, such as the ingestion of psychoactive substances or the strong change in the level of the body's own messenger substances through extreme exertion, deprivation of food, deprivation of sleep, etc. Ä. have - as a side effect - mind-altering consequences that are generally considered restrictions. This applies in particular to the ability to drive in any type of means of transport and in almost all professional activities.

Classification

Dieter Vaitl sets up a classification scheme according to the type of development or induction of altered states of consciousness :

- Spontaneous like daydreams and near-death experiences

- Physically and physiologically like fasting and sex

- Psychologically, for example through music, meditation or hypnosis

- Induced by diseases like epilepsy or brain injury

- Pharmacologically by psychoactive substances

- Religious change of consciousness: This describes the feeling of becoming one with God (with the so-called higher self, nature, the universe), as reported from all world religions (cf. mysticism ). An important characteristic can be ecstasy, i. H. strong, lightning-like to long lasting waves of feeling, followed by a phase of bliss, peacefulness and participation in the life of others (see enlightenment ). Near-death experiences can also be counted in this category.

species

- Sensory change in consciousness: This includes the apparent or real amplification of sensory perceptions or their mixing ( synaesthesia : "taste colors, smell sounds"), often caused by the consumption of mind-altering drugs .

- Changes in motor consciousness: This includes the impression of being able to undertake physically inexplicable actions (flight experiences, physical maximum performance) that are consciously experienced in a state of stasis, but by the person concerned (see also sleep paralysis , hypnagogic experience , dream yoga ).

- Targeted changes in consciousness: From a person - e.g. Sometimes with outside help - brought about a state of concentration on a question, a person or a goal. It is a common practice in many spiritual traditions, both in the West ( contemplation , certain forms of prayer and asceticism ) and in the East (meditation).

- Paranormal changes in consciousness: Speculative form of changes in consciousness, in which, for example, so-called precognitive experiences, i.e. H. the perception of future or distant events should be possible (cf. also seers ), also regressions into allegedly already lived lives under hypnosis.

Methods

Think

Thinking that leaves the familiar path - that is, thinking yourself in an unfamiliar way in unfamiliar areas - should have a sustainable and healthy mind-changing effect. There are a number of methodical (e.g. lateral thinking , education ) and a few non- methodical ( serendipity ) processes of mind-altering thinking. R. Kapellner writes about this that, from a subjective point of view, one can feel like thinking faster and more clearly. But it can also lead to feelings of alienation from the self, to a loss of self-control, accompanied by negative and positive emotions .

meditation

Meditation and other spiritual exercises can lead to a change in consciousness. In some of the exercises the ultimate goal is the experience of enlightenment, described, among other things, as the experience of the dissolution of the separation of the individual from all.

A distinction can be made between two opposing, complementary (i.e. complementary) basic methods. According to one, a change in consciousness is achieved through extreme concentration and extreme focus on one point (e.g. samatha ). According to the other, this happens in complete contrast to this through extreme opening and expansion to the whole around the practitioner through mindfulness (e.g. Vipassana ). “A certainty of closeness to the supernatural arises especially when the sacred reveals itself to the seeker, be it in a dream or in other images, which states of altered consciousness present the believer. The history of every religion, including that of the Judaic Christian, is always also a history of visions ”. Examples of manifestations of these methods can be found in all cultures and religions.

Psychoactive substances

Some types of mushrooms , herbs , LSD and mescaline show a mind-altering effect and were traditionally used in shamanic rituals. Such substances are also used in psycholytic psychotherapy .

Body's own messenger substances

The feeling of a change in consciousness is also possible in the context of the over- or under-production of the body's own messenger substances, which occur during physical exertion, monotonous rhythms, extreme joy, dehydration , hypoglycaemia and the like. Ä. be produced or inhibited. These include, for example, feelings of flow during sports, going to the disco and techniques in Islamic Sufism .

Stimulus deprivation

Another way of inducing states of altered consciousness is to reduce external stimuli (stimulus deprivation). This was used, among others, by monks in Tibet (e.g. by practitioners of Dzogchen ), but was also part of the practice in many other spiritual currents. The darkness and seclusion of underground chambers and caves reduces the stimulation of the sensory system. In absolute darkness and silence, among other things, there should be an unfamiliar expanse of the visual flow of thoughts. The so-called isolation tank also prevents sensory stimulation from your own body weight and supports the impression of a change in consciousness.

Conscious dreaming

The lucid dream , which has its systematic origins in Tibetan Buddhism, but has also been known as a physiological phenomenon in the West for several decades, is considered an unusual type of change in consciousness . The effects during such a lucid dream are in part similar to those of stimulus deprivation. Advanced practitioners should be able to fully control the dream environment. In this way they could overcome the limits of our waking consciousness in sleep.

Prevalence

The share of different states of consciousness in the human experience:

- 60% waking awareness

- 12% deep sleep

- 10% light sleep

- 8% dream sleep

- 4% Optionally altered states of consciousness

- 3% sub trance

- 2% daydreaming

- 1% sleep life

- 1% wake up experience

The occurrence of ASCs according to various studies.

| ASC | population | Proportion of positive answers (Passie, 2007) |

source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depersonalization | students | 23% 46% |

Roberts, 1960 Dixon 1963 |

| Hypnotic states | Students normal subjects |

40–60% 80–90% |

Shor 1960 As u. a. 1962 |

| Mystical states | students | 29% 30–40% 28% 45% |

Kokoszka 1992/93 Tart 1969 Palmer, 1979 Greeley & McGready 1979 |

| "Superficially altered states of consciousness" | Students normal subjects |

81% 72-89% 81.8% |

Kokoszka 1992/93 Shor 1960 Siuta 1987 |

| Religious experience | Normal population churchgoers |

36.4% 30–35% 50% 30–35% |

Hay & Morisy 1978, Hay 1979 Hardy 1970, Back & Bourque 1970, Greeley 1975 Wuthnow 1976 Glock & Stark 1965 |

Further prevalences according to Vaitl (2012) and Matthiesen (2007)

| ASC | Share of positive answers Vaitl (2012) |

source |

|---|---|---|

| “Extraordinary experience” such as extrasensory perception or paranormal experience |

total "almost 75%" | Bauer and Schtsche 2003 Beltz 2009 |

| Out of body experience | 22-36% | Alvarado 2000 |

| Matthiesen (2007) | ||

| Near death experience | 5-10% | Gallup & Procter 1982 Schmied et al. 1997 |

According to the frequently cited 1973 study by Erika Bourguignon, 90% of 488 societies examined around the world cultivate rituals and practices of changing consciousness. All cultures differentiate between pathological and healthy states of consciousness.

Phenomenology of Altered Consciousness

States of consciousness and structures of consciousness are external ascriptions and as such cannot be directly experienced. The phenomenological approach therefore concentrates on the immediate subjective experience and tries to identify structures and conditions with the help of questionnaires and systematization.

Arnold M. Ludwig (1966) distinguishes seven aspects of altered states of wakefulness:

- Change of thinking

- Disturbed sense of time

- Loss of control

- Change in emotionality

- Body schema change

- Change of perception

- Changed experience of meaning

Adolf Dittrich (1985, 1998) uses the APZ questionnaire ( Extraordinary Psychological Conditions ) to identify five “core experiences” of altered states of consciousness that are independent of the method used to achieve them. This includes:

- Oceanic Self-Delimitation (OSE)

- Fearful Ego Dissolution (AEI)

- Visual restructuring (VUS)

- Auditory change (AVE)

- Vigilance reduction (VIR)

There is also the PCI questionnaire (Phenomenology of Couscious Inventory) by Roland Pekala , which puts attention performance at the center of interest. As with the APZ / OAVAV, states of consciousness should be determined retrospectively (i.e. after an experience) on the basis of phenomenological parameters under standardized conditions. The questionnaire consists of 53 characteristics , which are divided into 12 “dimensions”. The ASASC questionnaire (Assessment Schedule of Altered States od Counsciousness) by Renaud van Quekelberghe (1991) is also based on a general focus on altered states of consciousness .

There are also a number of other questionnaire instruments, but these are mostly tailored to specific states of consciousness; for example the Near Death Experience Scale by Bruce Greyson (1983) for recording near death experiences or the Mystical Experience Scale by Ralph W. Hood (1975) for classifying mystical experiences. Despite various methodological difficulties and fundamental limitations of a scientifically conducted introspective or retrospective method, questionnaires such as the OAVAV and the PCI show good informative value and reliability .

Julien Silverman describes various features that characterize an altered state of consciousness:

- Disturbance of attention , concentration , judgment and memory

- Disturbed experience of time

- Difficulties in self-control and reality control

- Changes in emotionality, physical experience and meaning experience

In the past, many phenomenological studies have been carried out with the help of psychotropic substances and other techniques in order to specifically influence consciousness. Roland Pekala names psychedelic drugs, EEG-based biofeedback , meditation, hypnosis and cannabis use, among other things . In general, the reliability and validity of phenomenological research results are still being discussed today. The difficulty is that mental phenomena cannot be isolated. Likewise, there is no possibility of mapping these qualities of consciousness onto physiological or neural measured values and models for any scale for classifying quality of consciousness.

History of research and modeling

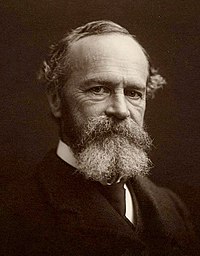

Particularly trance-like states aroused the interest of researchers in the 19th century and led to the first attempts at description and explanation. For the anthropologist Sir Edward Tylor , phenomena such as visions or obsessional belief were expressions of primitive cultures. Franz Brentano and William James were pioneers in the systematic descriptive research of subjective experience . The experimental psychologists Wilhelm Wundt and Edward Bradford Titchener created the first models of consciousness processes and attention control . Wilhelm Wundt arranged consciousness according to basic static elements , Brentano according to events and James according to processes. The philosophical current of phenomenology at the beginning of the 20th century led to the delimitation and definition of many qualitative characteristics of consciousness. This research approach is still the only access to any description and classification of mind-altering experiences. Using a descriptive, phenomenological approach, Traugott Konstantin Oesterreich (1921) and William James (1902) documented detailed descriptions of altered states of consciousness. The first systematic models of altered experiences of consciousness came from Richard Müller-Freienfels ( on the psychology of states of excitement and intoxication , 1910) and Siegfried Behn (1914). Out of the interest of the psychology of religion, Behn subdivides altered states of consciousness into supervise and supervise . The development of psychoanalysis , on the other hand, tended to lead again to psychiatization and pathologization of changed states of consciousness. With the rise of behaviorism , research into subjective processes and structures of consciousness was almost given up. The research method of introspection fell into disrepute at the beginning of the 20th century. It was accused by representatives of Gestalt psychology of only paying attention to the quality and intensity of the experience categories, but not depicting the level of meaning. One of the main criticisms of introspection was the finding that data obtained introspectively were usually obtained in a retrospective process. The test persons have to remember the changed conditions, name and describe them. This problem seems to be at least partially eliminated by modern imaging methods that can record changes in real time.

In Europe, the “classic introspection” of the 19th century was increasingly developed further in phenomenological psychology, psychoanalysis and gestalt psychology, while in the USA it was supplanted by behaviorism in particular. Last but not least, the task of introspection was a political, zeitgeist-borne change in the prevailing scientific methods.

It was not until the 1960s, with the so-called cognitive turn , that introspective methods became a legitimate subject of research again. The clinical-scientific research into hypnosis, the increasing interest in dreams and sensory deprivation, and especially the new technical possibilities to carry out empirical and experimentally manipulable investigations, again led to a greater interest in altered states of consciousness. It has been argued that the correlations between mental and neural states assumed in neuroscience can be better used if the mental states are examined better. The behaviorists' demands for predictability and control of behavior were also not fulfilled to the extent expected for a scientific approach. The switch back to methods of introspection was not a scientific revolution, but a broad process that was also supported by socio-political forces and did not completely supplant the old approaches. The work of David Lieberman turned out to be similar to that of John B. Watson sixty years earlier, who founded behaviorism.

In the New Age movement, the introspective methods for altered states of consciousness and, in particular, through the use of psychedelic substances, also met with broad popular scientific interest. The reception of the most important publications of this period was summarized by Charles Tart in 1970 in his popular work Altered States of Consciousness . Based on the psychological aspect of states of consciousness, several concepts for describing and mapping the subjective space of experience have developed since then. The heyday of introspection and experimentation with psychedelic substances ended in the 1970s. On the one hand, a globally restrictive drug policy made many research approaches difficult or impossible. On the other hand, the emergence of many new technical possibilities such as electroencephalography inspired hope for quick and in-depth knowledge. Modern imaging methods from brain research such as positron emission tomography (PET) or functional magnetic resonance tomography (fMRI) can clarify which brain structures and processes are involved in the creation and maintenance of consciousness. However, the expected breakthrough, such as deciphering the “seat of consciousness” or the precise relationship between frequency bands in the EEG and the experience associated with it, did not materialize.

In medicine and psychiatry , consciousness itself is not defined today, but characteristics of experience such as clarity, vigilance (alertness) and memory. Just like phenomenal consciousness itself, states of consciousness also have an evolutionary history and thus functional evolutionary advantages. Evolutionary approaches also play a role in consciousness research; however, this approach is still in its infancy with regard to research into altered states of consciousness.

Models

The models of states of consciousness discussed historically and currently are very heterogeneous; this also applies to the neuroscientific approaches that are important today. All attempts to trace back changes in consciousness to central mechanisms of brain physiology and thus to simplify and standardize the models have so far failed. Nevertheless, neuroscientific models are still in the majority in current research. In addition, models from psychology serve more as explanatory approaches and frameworks for interpretation. Models, which are supposed to describe all states of consciousness, are usually set up without a comprehensive empirical check. In contrast, special models and explanatory approaches that describe individual or a few states of consciousness are usually better investigated experimentally. Traditional, religious models still have their representatives and are increasingly playing a role in psychotherapeutic treatment methods. The same applies to models of consciousness and psychotherapies in transpersonal psychology .

Descriptive models

Klaus Thomas leads the distinction between under watch and monitor states of Siegfried Behn continues and extends it by one hand under watch differentiated states of consciousness in "states of sleep" and "religious state" and the other four new classes of except waking introduces states.

The hypnosis researcher Erika Fromm , based on Sigmund Freud's distinction between primary processes and secondary processes in psychological experience, develops the theory that every state of consciousness is on a continuum between a primary process and a secondary process. She then expands this to five “dimensions”, whereby the experience varies, for example, between fantasy and reality orientation, visual imagination and conceptualization. Fromm tries to explain the dynamics of dream work, but also how hypnosis works. With the help of a targeted variation between primary and secondary processes, approaches for the explanation and therapy of psychotic states should be made possible.

Neurophysiological models

Models of cognitive neuroscience are based on the thesis that neural structures and processes are an important or essential part of the explanations for VBZs. In the field of neuroscience there are several individual hypotheses on specific statements about the formation of consciousness processes. However, these are far from making general and universal statements about the emergence of qualities of consciousness or even about states of consciousness.

For example, NMDA synapses play an important role in the formation and maintenance of mental representations. It is also known that the colinergic neurotransmitter system controls the sleep-wake rhythm and the REM phases. Pharmacological disorders of these synapses can lead to a change in the representation of external relationships; Perceptual contents lose their familiar structure and are experienced as "extraordinary".

Changes in the state of consciousness are closely linked to the so-called arousal system, which maintains a basic activation of the brain. Different regions of the brain, each with different functions, are included in this system. These are also referred to as LCCS ( Limited Capacity Control System , dt. ' Limited Capacity Control System '). This LCCS is responsible for both sustained alertness and temporary selective attention. If stimuli are now assessed as new and complex, the LCCS is activated; its limited ability to process reflects its limited ability to pay attention.

Attention performances

In many models and concepts, attention is not just one characteristic of consciousness among many, but rather it represents the central quality of conscious being. On the basis of the variation in attention, the variation in consciousness is then generally described and divided into various properties for detailed analysis.

The American psychologist and neurophysiologist Julien Silverman developed a model of altered states of consciousness in 1968 based on his experiences with schizophrenia patients and LSD users . To this end, he particularly looked at the attentional performance, which he modeled on the basis of psychological and neurophysiological empirical studies. Each feature of the line of attention describes a reaction and a possible reaction mechanism. The five dimensions of these attention characteristics are, for example, the ability to differentiate and distractibility. Silverman assigns a certain “attention style” to each person and changed states of consciousness can then be characterized using these parameters. This creates a multidimensional framework with the help of which states of consciousness can be classified.

Steven M. Fishkin and Ben Morgan Jones also focused on attention and its parameters. Their model is based on the statement that the content of consciousness is only determined by what and how something comes into attention. The attention works like a window that controls everything that can come into consciousness. This window now varies in various parameters such as size and movement speed. Fishkin and Jones distinguish a total of eight parameters and can thus assign specific characteristics of these parameters to each state of consciousness.

Continuum of ergotropic and trophotropic excitation

In 1971, the psychopharmacologist Roland Fischer presented his model of states of consciousness in Cartography of the ecstatic and meditative states . His work is based on years of experimentation with psychedelic substances such as psilocybin and LSD. Fischer builds on the concept of two reciprocal central nervous systems, the ergotropic system and the trophotropic system . The “normal” experience then moves on a continuum of ergotropic arousal to an overexcited state, to ecstatic and psychotic experiences, and on the continuum of trophotropic arousal to an underexcited state such as the samadhi state of the yoga tradition. For fishermen, the ergotropic direction of overexcitation is the one known and customary in the Western tradition, the trophotropic direction is the one evoked by meditative exercises in the Eastern traditions.

Both extremes also mean an orientation of attention to inner-psychological processes and away from sensory perception. Fischer believes that he can prove the mutual exclusion of both excitation systems on the basis of physiological data such as EEG patterns and eye movements. For example, in the case of hallucinatory experiences, more desynchronized electroencephalograms can be detected, whereas in the case of deep meditative immersion, a high level of synchronization. He also uses the relationship between sensory and motor activity to differentiate between states of consciousness. If the sensory activity is increased and the motor activity decreased, this is a characteristic for dream sleep, daydreams or hallucinations. The so-called S / M value is then high. In later publications, Fischer differentiates between three "space-times", physical, sensory and cerebral space-time. Accordingly, external objects are perceived in sensory space-time and given a meaning in cerebral space-time. This differentiates between the physical world, the world of meaning and the world of “raw” sensory data, whereby in healthy people all three worlds continuously exchange information. Changed states of consciousness are then each characterized by specific differences in these space-times.

Fischer's model of the excitation scale thus postulates a mutually exclusive existence of “normal” and exalted states. “I experience” is in the middle of the scale, “self experience” at both extremes. A connection between the two would thus be possible in the middle; that is, in dreams and in hallucinatory states. With his approach, Fischer combines the western and eastern division of altered states of consciousness on the basis of a neurophysiological theory of arousal.

Functional neuroanatomy

Functional hypofrontality

The human brain is made up of neuroanatomical structures that have evolved over the course of evolution. If one considers these structures as a hierarchical organization from this point of view, then the “layers of consciousness” can also be assigned to them. From this, Dittrich (2003) developed a hierarchical model of consciousness, at the top of which is the dorsolateral region. In this model, changed states of consciousness are explained by the temporary failure of various prefrontal regions. It turns out that all investigated VBZs correlate with an inhibition of the frontal region. The absence or reduction of prefrontal functions - such as self-modeling, thinking, and memory access - makes other regions of the cerebral cortex more active. This explains many phenomenological changes during dreaming, meditation, and taking psychedelic substances.

Disconnectivity

A change or dissolution of the functional connectivity (disconnectivity) between thalamus and cortex is an explanatory concept for changed states of consciousness. Both are usually connected to each other via the gamma oscillation of 40 Hz (oscillatory resonance activity).

Neurochemical models

CSTC loop model

Altered states of consciousness can be triggered by endogenous (endogenous) or exogenous neurotransmitters . Many experiments make use of this possibility in order to research the neurophysiological correlates of altered states of consciousness. The Swiss psychiatrist Franz Xaver Vollenweider studies the effects of hallucinogens in the brain with the help of imaging techniques. From this he created a control loop model, which explains psychedelic symptoms as a result of a reduced inhibition of mental activities. If the thalamus can no longer adequately filter the stimuli, the cortex is “sensory flooded”. This therefore loses the ability to integrate information, which can lead to ego dissolution and depersonalization . The inhibitory influence of the striatum on the thalamus prevents the "sensory overflow". The CSTC model comprises the four neurotransmitters serotonin , GABA , dopamine and glutamic acid and describes five control loops. Vollenweider's work shows, among other things, that psychedelic and psychotic symptoms cannot be assigned to individual brain regions. He was able to show that the dimensions in the APZ questionnaire (see phenomenology) correlate with a metabolic change.

Meta-representations

Another theory is based on the notion of "meta-representations". It says that not just individual neurons, but entire groups represent a certain sensory stimulus. If the NMDA synapses of these groups are then disturbed, stable perceptual content falls apart and is perceived as "exceptional".

pharmacology

Psychedelic substances can cause a targeted change in the state of consciousness. The known compounds can be divided into four classes according to substance class and effect:

- serotonergic psychedelics like LSD and mescaline

- psychedelic and dissociative anesthetics

- entactogenic

- other substances like cannabis and cocaine

The effect of psychedelic substances is largely determined by the “set”, the attitudes and expectations of the consumer, as well as the “setting”, i.e. the circumstances of ingestion or administration. According to Timothy Leary , these conditions make up 99% of the experience. This assessment is confirmed in principle today, which results in restrictions for placebo- controlled studies. But a broad recognition of psychotherapies based on psychedelic substances is also difficult - because of the dependence of their effects on the set and setting and thus the possibility of achieving reliable treatment success. Nevertheless, experiments with psychedelics have been firmly established in basic neuroscientific research for several years. According to Dieter Vaitl, pharmacologically induced changes in consciousness can no longer be controlled by the individual, whereas “learned states of consciousness”, even if they are not phenomenologically different, can still be controlled and in particular terminated by the individual.

Techniques for activating endogenous neurotransmitters

According to Adolf Dittrich et al. A number of traditional and modern psychotherapeutic techniques are suitable for producing altered states of wakefulness by influencing the body's own neurotransmitters. These include, for example , stimulus withdrawal ( deprivation ), overstimulation, sleep deprivation , fasting , physical exercises, breathing techniques, sex, pain , music, dance, hypnosis and meditation.

Systems theoretical model according to Charles Tart

Charles Tart describes normal consciousness not as a natural state, but as a complex construction that results from the interaction of many subsystems. The basis of the consciousness system therefore consists of given physical and psychological structures, the ability for selective attention and programmable structures. Consciousness fulfills the function of perceiving and coping with the environment. It only achieves this through a series of stabilization processes. A change towards a clearly definable VBZ then takes place through a disruption in the form of stimuli or other influences. To this end, Tart differentiates between influences that restructure normal experience and those that favor structures to establish a changed state of consciousness.

Models in Religions

There are also models of altered states of consciousness in different religions. The most extensive experiences and maps can be found in the so-called Eastern religions such as Buddhism and the yoga tradition. The characteristic of these models is the focus on meditation-specific states, i.e. states that are realized with the help of meditation or similar methods. Another specific feature of these religious models is their normative orientation. VBZs are divided into desirable higher and lower states and are arranged hierarchically. In the Christian tradition, too, there are isolated level models of consciousness. So describe pseudo-Dionysius and John of the Cross a three-part way Teresa of Avila a "Interior Castle" in the seven "apartments" are located.

Features of individual dispositions

variability

Roland Fischer describes the property of variability in test persons as a characteristic of a psychophysical reactivity of humans. Subjects with a high variability react more strongly to hallucinogens . It is believed that they can better compare the drug experience with the ordinary experience.

absorption

The individual characteristic of absorption describes the ability of a person to focus strongly on perceptual content. According to Ulrich Ott , it correlates with neurobiological foundations. Absorption is explored in the context of hypnosis, dissociative processes, and general attention control. In 1974 the American psychologist Auke Tellegen developed a questionnaire, which led to a classification of characteristics in the Tellegen Absorption Scale (TAS). This has since been modified several times.

The disposition “absorption” can also be described as an openness to experience. Factor analyzes showed that all aspects used correlate positively with one another. In 1992, Tellegen identified six "dimensions":

- intense emotional response to moving stimuli such as music

- Synesthesia

- increased visual experience (cognition)

- Forgetfulness

- vivid pictorial memories

- increased mindfulness

The disposition to absorption has a high hereditary share, with up to 44% even the highest value for a character trait according to the TCI ( Temperament and Character Inventory ) . This finding suggests that neurophysiological functions and structures are central to the ability to absorb. The influence of serotonergic and dopaminergic systems is suspected , but more precise findings are not known. It is also known that upbringing also has an influence on the ability to absorb.

Application and use of altered states of consciousness

The worldwide spread of rituals and techniques for changing consciousness is in the context of medical and religious applications. For example, practices in Siberian shamanism or meditation techniques are important anthropological constants. But also in modern medicine and psychotherapy, altered states of consciousness such as hypnosis, autogenic training or imagination techniques are used. The use of psychoactive substances can also be used to support various forms of therapy, such as intensifying deep psychological treatment in psycholytic psychotherapy. Transpersonal therapy methods such as holotropic breathing also use changed states of consciousness.

Seen worldwide, the use of altered states of consciousness is clearly pronounced in many cultures. Their application is then mostly practiced in a ritual, cultural setting in order to control and maximize their effect. The benefits range from social integration, initiation , life training, acquisition and imparting of knowledge, artistic entertainment and divination to enlightenment. Psychological and physical healing applications as well as shamanic rituals relating to birth, death and dying play a special role .

Arnold M. Ludwig sees the benefits of VBZs not only in the psychological and social area, but also in the biological one. Altered states of consciousness then represent a possibility of adaptation to unusual living conditions. The spread and the general potential to realize them make up the general meaning of VBZs for Ludwig. He also mentions a number of “misapplications” (maladaptive expressions) such as the escape from reality with the help of psychedelic drugs.

literature

Overviews

- Thorsten Passie: States of Consciousness: Conceptualization and Measurement. Lit Verlag, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8258-0287-5 .

- Dieter Vaitl: Altered states of consciousness: Basics - Techniques - Phenomenology. Schattauer, 2012, ISBN 978-3-7945-2549-2 .

- Andrzej Kokoszka: States of Consciousness. (Emotions, Personality, and Psychotherapy). Springer, 2007, ISBN 978-0-387-32757-0 .

- Andreas Resch (Ed.): Changed states of consciousness. Innsbruck 1990, ISBN 3-85382-044-1 .

- Etzel Cardena (Ed.), Michael Winkelman: Altering Consciousness - Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Praeger Publishers, Santa Barbara 2011, ISBN 978-0-313-38308-3 .

classic

- Charles Tart: Altered States of Consciousness. John Wiley & Sons, New York 1969.

- G. William Farthing: Psychology of Consciousness: Psych Consciousness & Reaching Full Potential. Prentice Hall, 1991, ISBN 0-13-728668-6 .

- RJ Pekala: Quantifying Counsciousness. Springer, Berlin 1991, ISBN 0-306-43750-3 .

- Erika Bourguignon: Religion, Altered States of Consciousness and Social Change. Ohio State University Press, 1973, ISBN 0-8142-0167-9 .

Biological psychology

- Niels Birbaumer, Robert F. Schmidt: Biological Psychology. 5th edition. Springer, 2002, ISBN 3-540-43480-1 .

Neurobiology

- Thomas Metzinger : Neural Correlates of Consciousness: Empirical and Conceptual Questions. With PR, 2000, ISBN 0-262-13370-9 .

Religious Psychology

- Sylvester Walch: Dimensions of the human soul - healing and development through altered states of consciousness. Patmos Verlag, 2012, ISBN 978-3-8436-0246-4 .

- Adolf Dittrich, Albert Hofmann , Hanscarl Leuner (eds.): Worlds of consciousness. Volume 1. VWB, 1993, ISBN 3-86135-401-2 .

Specifically on types and methods of changing consciousness

literature

- Rudolf Kapellner, Gerd Gerken (ed.): How the mind becomes superior . With a contribution by R. Kapellner: Awareness and Floating . Verlag Junfermann, Paderborn 1993. ISBN 3-87387-118-1

- Barbara Schachenhofer: Health consciousness versus deductible: about the need to broaden our consciousness with regard to our health , university publication Linz University, Trauner University Press, Linz 1997. ISBN 3-85320-854-1

Web links

- Drug-induced and other extraordinary states of consciousness

- A new culture with old traditions or: from primitive cult to culture

Individual evidence

- ↑ Thomas Metzinger, Ralph Schumacher: Awareness. In: Hans-Jörg Sandkühler (Hrsg.): Encyclopedia Philosophy. 2010.

- ↑ a b Thorsten Passie: States of Consciousness. Lit Verlag, Hamburg 2007, p. 9.

- ↑ Metzinger: Basic Course Philosophy of Mind. B-13, p. 421.

- ↑ Dieter Vaitl: Changed states of consciousness: Basics - Techniques - Phenomenology. Schattauer, 2012, p. 13.

- ↑ Marcel Bisiach: Consciousness in contemporary science. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1988, p. 3 ff.

- ↑ Thomas Metzinger: Subject and Self-Model. mentis Verlag, Paderborn 1999, p. 183.

- ^ Arnold M. Ludwig: Altered states of consciousness. In: Archives of General Psychiatry. 15, pp. 225-234.

- ^ G. William Farthing: Psychology of Consciousness. Prentice Hall, 1991/2, p. 18.

- ↑ Gerhard Roth : The brain and its reality. Cognitive Neurobiology and its Philosophical Consequences. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt, p. 22.

- ↑ Dieter Vaitl: Changed states of consciousness: Basics - Techniques - Phenomenology. Schattauer, 2012, p. 14.

- ↑ RJ Pekala declares states that are differentiated as “ subjective sence of (being in) an altered state ” (SSAS). Ronald J. Pekala: Quantifying Consciousness - An empirical Approach. Plenum Press, New York 1991, p. 83.

- ↑ This not only includes external information such as sensory perceptions, but also unconscious physical and mental events.

- ↑ Atti Revounso, Sakki Kallio, Pilleriin Sikka: What is an altered state of consciousness? In: Philosophical Psychology , Vol. 22, No. 2, April 2009, pp. 187-204.

- ^ Stanley Krippner: Altered states of consciousness. In: J. White (Ed.): The highest state of consciousness. John Wiley, New York 1972, p. 1.

- ↑ a b Ronald J. Pekala: Quantifying Consciousness - An empirical Approach. Plenum Press, New York 1991, pp. 43/44.

- ↑ Stephan Matthiesen, Rainer Rosenzweig : From the senses: dream and trance, intoxication and rage from the point of view of brain research. mentis Verlag, Paderborn 2007, p. 11.

- ↑ See on this: Rudolf Kapellner, Gerd Gerken (ed.): How the mind is considered: Mind Management , Junfermann Paderborn 1993, 391 pp. ISBN 3873871181

- ↑ Quotation from: Walther Bühler: Meditation as a path of knowledge, [Studies and experiments 2 - 2nd expanded edition]. Free Spiritual Life Publishing House, Stuttgart 1972, 55 pp. ISBN 9783772500329

- ↑ Based on data from Schredl (1999), Koella (1988) Kugler u. a. (1984), Thomas (1973); quoted from Thorsten Passie: states of consciousness. Lit Verlag, Hamburg 2007, p. 11.

- ↑ Quoted from Thorsten Passie: states of consciousness. Lit Verlag, Hamburg 2007, p. 14. See also Andrzej Kokoszka: States of Consciousness: Models for Psychology and Psychotherapy. Springer, 2007, p. 38 ff.

- ↑ Dieter Vaitl: Changed states of consciousness: Basics - Techniques - Phenomenology. Schattauer, 2012, ISBN 978-3-7945-2549-2 , p. VII.

- ↑ Adolf Dittrich (ed.): Worlds of consciousness. Vol. 1, VWB, 1993, p. 26.

- ↑ The APZ questionnaire has meanwhile been expanded to become the OAVAV questionnaire

- ^ Bruce Greyson: The near-death experience scale: Construction, reliability, and validity. In: Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease , 171 (6), pp. 369-375.

- ↑ Ralph W. Hood: The construction and preliminary validation of a measure of reported mystical experience. In: Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion , No. 14 (1), pp. 29-41.

- ↑ A detailed table for questionnaire instruments can be found in T. Passie (2007), p. 70.

- ↑ Thorsten Passie: States of Consciousness. Lit Verlag, Hamburg 2007, pp. 71-73.

- ^ J. Silverman: A paradigm of the study of altered states of consciousness. In: The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1968 (11), 114, pp. 1201-1218.

- ↑ Brigitte Falkenburg: Myth determinism. Springer, 2012, ISBN 978-3-642-25097-2 , p. 99 and p. 177-185.

- ↑ Ronald J. Pekala: Quantifying Consciousness - An empirical Approach. Plenum Press, New York 1991, pp. 17-19.

- ^ Siegfried Behn: About the religious genius. In: Archives for the Psychology of Religion. 1, pp. 45-67.

- ↑ Dieter Vaitl: Changed states of consciousness: Basics - Techniques - Phenomenology. Schattauer, 2012, p. 3.

-

↑ Ronald J. Pekala notes that during the 1930s in the United States, the term awareness (consciousness) virtually appears in no psychological publication.

Ronald J. Pekala: Quantifying Consciousness - An empirical Approach. Plenum Press, New York 1991, pp. 19-22. - ↑ Heinrich Balmer: Objective Psychology - Understanding Psychology. Perspectives of a Controversy. Beltz Verlag, Weinheim 1982, ISBN 978-3-407-83045-6 , p. 82.

- ↑ Ronald J. Pekala: Quantifying Consciousness - An empirical Approach. Plenum Press, New York 1991, pp. 23-25.

- ^ David A. Lieberman: Behaviorism and the Mind: A (limited) Call for a Return to Introspection. In: American Psychologist , 1979, No. 34, pp. 319-333.

- ^ John B. Watson: Psychology as a behaviorist views it. Psychological Review 20, 1913, pp. 157-177.

- ↑ Ronald J. Pekala: Quantifying Consciousness - An empirical Approach. Plenum Press, New York 1991, pp. 79/80.

- ↑ See for example Vilayanur Ramachandran: A Brief Journey through Mind and Brain. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 2005.

- ↑ Dieter Vaitl: Changed states of consciousness: Basics - Techniques - Phenomenology. Schattauer, 2012, ISBN 978-3-7945-2549-2 , p. VIII.

- ↑ Hannes Hempel: In the MRI: Influence of the absorption capacity. Justus Liebig University, Giessen 2009, p. 34.

- ↑ Klaus Thomas: Meditation in research and experience in worldwide observation and practical guidance. Thieme Georg Verlag, Stuttgart 1973, ISBN 3-13-497201-8 .

- ↑ Thorsten Passie: States of Consciousness. Lit Verlag, Hamburg 2007, pp. 25-30.

- ↑ a b c Dieter Vaitl: Changed states of consciousness: Basics - Techniques - Phenomenology. Schattauer, 2012, ISBN 978-3-7945-2549-2 , p. 24.

- ↑ Niels Birbaumer, Robert F. Schmidt: Biological Psychology. 5th edition. Springer, 2002, p. 519 ff.

- ↑ Thorsten Passie: States of Consciousness. Lit Verlag, Hamburg 2007, p. 16, table 5 selection.

- ↑ Steven M. Fishkin, Ben Morgan Jones: Drugs and consciousness: an attentional model of consciousness with applications to drug-related altered states. In: A. Arthur Sugarman, Ralph E. Tarter (Eds.): Expanding dimensions of consciousness. Springer, New York 1978.

- ↑ Ronald J. Pekala: Quantifying Consciousness - An empirical Approach. Plenum Press, New York 1991, p. 41 ff.

- ↑ Thorsten Passie: States of Consciousness. Lit Verlag, Hamburg 2007, p. 38.

- ↑ Thorsten Passie: States of Consciousness. Lit Verlag, Hamburg 2007, pp. 42/43.

- ↑ Ronald J. Pekala: Quantifying Consciousness - An empirical Approach. Plenum Press, New York 1991, p. 42.

- ↑ Thorsten Passie: States of Consciousness. Lit Verlag, Hamburg 2007, pp. 44-48.

- ^ Nicolas Langlitz: Neuropsychedelia: The Revival of Hallucinogen Research since the Decade of the Brain. University of California, Berkeley 2007, p. 7.

- ↑ Dieter Vaitl: Changed states of consciousness: Basics - Techniques - Phenomenology. Schattauer, 2012, ISBN 978-3-7945-2549-2 , p. 219.

- ↑ Adolf Dittrich: Worlds of Consciousness. Volume 1. 1993, pp. 35/36.

- ^ Charles Tart: Transpersonal Psychology. Walter-Verlag, Olten / Freiburg im Breisgau 1978, ISBN 3-530-87050-1 , p. 292 ff.

- ↑ Thorsten Passie: States of Consciousness. Lit Verlag, Hamburg 2007, pp. 41/42.

- ↑ Ulrich Ott: States of absorption: In search of neurobiological foundations. In: GA Jamieson (Ed.): Hypnosis and Consciousness States: the cognitive-neuroscience perspective. Oxford University Press, New York 2007, p. 261 ff.

- ^ A. Tellegen, G. Atkinson: Openness to absorbing and self-altering experiences ('absorption'), a trait related to hypnotic susceptibility. In: Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1974, No. 83, pp. 268-277.

- ↑ Dieter Vaitl: Changed states of consciousness: Basics - Techniques - Phenomenology. Schattauer, 2012, pp. 205–211.

- ↑ Stephan Matthiesen, Rainer Rosenzweig From the senses: dream and trance, intoxication and rage from the perspective of brain research. mentis Verlag, Paderborn 2007, p. 64.

- ↑ Thorsten Passie: States of Consciousness. Lit Verlag, Hamburg 2007, p. 16, table 5 selection.

- ↑ Adolf Dittrich (ed.): Worlds of consciousness. Vol. 1, VWB, 1993, p. 133 ff.

- ↑ Adolf Dittrich (ed.): Worlds of consciousness. Vol. 1, VWB, 1993, pp. 21-46.

- ^ Arnold M. Ludwig: Altered States of Consciousness. In: Charles Tart (Ed.): Altered States of Consciousness. HarperCollins, New York 1990, 3rd Edition, pp. 18-21.