Menrva

Menrva or Menerva is the name of an Etruscan goddess . She was one of the most important Etruscan deities and corresponds to the Roman Minerva and the Greek Athena .

Origin of name and spelling

The name of the deity is native to ancient Italy. It is widely believed to be of Etruscan origin and later adopted by the Romans and other Italian cultures. According to another opinion, it comes from Latin and was then translated into the Etruscan language . Initially, the Etruscan name was Menerva and was stressed on the second syllable . From the 5th century onwards, the emphasis on the first syllable was often shifted in Etruscan language and internal vowels were dispensed with, so that the name changed to Menrva . In Etruscan inscriptions, the spelling Menrva predominates .

Representation and aspects

Although her name is not recorded on the Etruscan bronze liver of Piacenza , which lists all the Etruscan gods of lightning, the Etruscan Menrva is almost certainly a goddess of lightning. Occasionally the goddess Tecum noted on the bronze liver is identified with Menrva. In any case, Minerva was known to the Romans as one of the nine deities who could throw lightning. In Etruscan art, she is also depicted with a lightning bolt and wings. These attributes, which speak for a weather deity , distinguish her from the Greek Athena, which is why her cult cannot originate from Greece.

The Etruscans viewed Athena as the Greek equivalent of their goddess and therefore often represented her in art with attributes of Athena. As the goddess of war, Menrva appears with a helmet, shield, spear, animal skin ( aigis ) and breastplate . Often the gorgon head of Medusa ( Gorgoneion ) can be seen on her upper body. In other depictions, however, she wears a dress ( peplos ) with stylish folds, a diadem or earrings. Only a spear, a helmet or the Gorgoneion identify her as the goddess of war. There is also the owl of Athena as an attribute of the Menrva.

Menrva was venerated in numerous sanctuaries , including the temple of Punta della Vipera on the territory of the important Etruscan city of Cisra ( Cerveteri ). A terracotta - statue with helmet and inscriptions on ceramics refer to Menrva as authoritative goddess of the sanctuary. Another famous place of cult of Menrva was the Portonaccio sanctuary of Veio ( Veji ). She was almost certainly venerated in the sanctuary of Vipsul ( Faesulae ). Their votive statues can be found all over Etruria and also in the Po Valley and in Campania .

Menrva was also a goddess of health and healing. In their sanctuaries were terracotta - sculptures in the form of body parts as votive offerings found, suggesting that their followers believed by it were healing powers. The Romans worshiped the goddess in her healing function as Minerva Medica . Menrva was probably also used as an oracle in her shrines to interpret the signs of the gods ( divination ). Her connection to prophecy is also shown by a bronze mirror on which she is depicted together with the divination Lasa Vecu .

Menrva also appeared as a guardian of children. A notable myth is about the Maris babies depicted on two bronze mirrors. In both depictions, the babies, who all have Maris as their first name, seem to disappear one after the other in a large amphora or a crater or to emerge from them under the guidance of Menrva . Menrva has exposed one breast on a mirror, suggesting that she will breastfeed the babies. The babies could be newborn gods protected and cared for by the goddess and her entourage. The scene cannot be interpreted conclusively because this Etruscan myth has not been passed down. The Greek Athena also protects infants in the myth.

Unlike Athena, who is nicknamed Parthenos for “the virgin”, Menrva seems to have entered into love affairs. There are many indications that Hercle is her husband, that is, the hero and later deified Heracles . Both appear on a mirror in a loving pose and can be clearly identified by the inscription. Further mirrors allow at least the conclusion that Menrva and Hercle are depicted as lovers. Menrva and Hercle are shown on a mirror with a child who is named Epiur in another place .

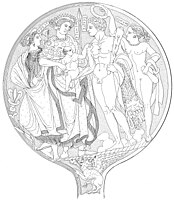

The Etruscans adopted numerous motifs from the myths around Athena. On a bronze mirror, Menrva, like Athena, is born from the head of the supreme god Tinia ( Zeus ). Menrva, like Athena, is the protector of the heroes Hercle (Heracles) and Perse ( Perseus ). One of the most popular Greek myths in Etruria was the judgment of Paris , who as Elcsntre ( Paris Alexandros ) had to decide a beauty contest between Turan ( Aphrodite ), Uni ( Hera ) and Menrva (Athene). The scene can be found on several bronze mirrors and on two painted wall panels from Cerveteri, the Boccanera panels. You can recognize Menrva by her helmet or spear.

In contrast to the Roman triad of Jupiter , Juno and Minerva, which were worshiped on the Capitol in a common temple , the corresponding Etruscan gods Tinia, Uni and Menrva were neither represented as a trinity nor worshiped together.

Bronze mirror with menrva

literature

- Giuliano Bonfante , Larissa Bonfante : The Etruscan Language. An Introduction. 2nd Edition. Manchester University Press, Manchester / New York 2002, ISBN 0719055407 .

- Nancy Thomson de Grummond , Erika Simon (eds.): The Religion of the Etruscans. University of Texas Press, Austin 2006, ISBN 9780292721463 .

- Nancy Thomson de Grummond: Etruscan Myth, Sacred History and Legend. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia 2006, ISBN 9781931707862 .

- Sybille Haynes : Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History. Getty Publications, Los Angeles 2000, ISBN 0892366001 .

- Jean-René Jannot: Religion in Ancient Etruria. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison 2005, ISBN 9780299208448 .

- Ambros Josef Pfiffig : Religio Etrusca. Sacred places, gods, cults, rituals. Academic Printing and Publishing Company , Graz 1975, ISBN 3201009083 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Nancy Thomson de Grummond: Etruscan Myth, Sacred History and Legend. P. 71.

- ^ Nancy Thomson de Grummond, Erika Simon: The Religion of the Etruscans. P. 59.

- ^ Giuliano Bonfante, Larissa Bonfante: The Etruscan Language: An Introduction. P. 81.

- ^ Ambros Josef Pfiffig: Religio Etrusca. Sacred places, gods, cults, rituals. P. 258.

- ^ Jean-René Jannot: Religion in Ancient Etruria. Pp. 147, 158.

- ^ Nancy Thomson de Grummond: Etruscan Myth, Sacred History and Legend. P. 71.

- ^ Nancy Thomson de Grummond: Etruscan Myth, Sacred History and Legend. Pp. 71-72.

- ^ Sybille Haynes: Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History. P. 184.

- ^ Nancy Thomson de Grummond, Erika Simon: The Religion of the Etruscans. P. 59.

- ^ Sybille Haynes: Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History. P. 252.

- ^ Jean-René Jannot: Religion in Ancient Etruria. P. 147.

- ^ Nancy Thomson de Grummond: Etruscan Myth, Sacred History and Legend. P. 72.

- ^ Sybille Haynes: Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History. P. 184.

- ^ Nancy Thomson de Grummond: Etruscan Myth, Sacred History and Legend. P. 72.

- ^ Nancy Thomson de Grummond: Etruscan Myth, Sacred History and Legend. Pp. 74-75.

- ^ Ambros Josef Pfiffig: Religio Etrusca. Sacred places, gods, cults, rituals. P. 354.

- ^ Nancy Thomson de Grummond: Etruscan Myth, Sacred History and Legend. P. 75.

- ^ Ambros Josef Pfiffig: Religio Etrusca. Sacred places, gods, cults, rituals. P. 349.

- ^ Giuliano Bonfante, Larissa Bonfante: The Etruscan Language. An Introduction. P. 161.

- ^ Giuliano Bonfante, Larissa Bonfante: The Etruscan Language. An Introduction. P. 201.

- ^ Nancy Thomson de Grummond: Etruscan Myth, Sacred History and Legend. P. 78.

- ^ Ambros Josef Pfiffig: Religio Etrusca. Sacred places, gods, cults, rituals. P. 34.