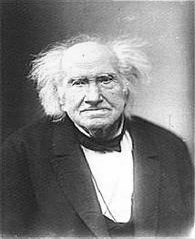

Eugène Chevreul

Michel Eugène Chevreul (born August 31, 1786 in Angers , France , † April 9, 1889 in Paris ) was a French chemist , basic researcher in the field of fat synthesis, founder of fat chemistry and the modern theory of colors .

Life

Eugène Chevreul's father was a highly respected surgeon. From 1799 he attended the École Centrale in Angers, where he learned Latin, Greek, Italian, mineralogy, physics and chemistry. In 1803 he moved to Paris and studied with Antoine François de Fourcroy and Louis-Nicolas Vauquelin . In 1804 Vauquelin received the chair of applied chemistry at the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle , and Chevreul became his assistant. In 1813, Chevreul became a professor of natural sciences at the Lycée Charlemagne .

In 1818 he married Sophie Davalet (1794–1862). The two had a son, Henri Chevreul (1819-1889).

Chevreul applied for a patent for non-drip candles and founded a candle manufacturer together with Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac in 1824. In 1824 he was by Louis XVIII. appointed director of the tapestry manufactory . He also taught at the Lycée Charlemagne and worked on a two-volume work on organic analysis.

In 1826 Chevreul became a member of the Académie des sciences and a foreign member ("Foreign Member") of the Royal Society . In 1830 Chevreul wrote a book on color theory, but it was not published until 1839 ( De la Loi du Contraste Simultané des Couleurs ). In 1832 he became a member of the Société Royale d'Agriculture and was its president from 1849. Since 1834 he was a corresponding member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences and since 1858 a foreign member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences . In 1860 he was elected a member of the Leopoldina . In 1862 his wife died. In 1865 he was elected a foreign member of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and in December 1866 an honorary member ( Honorary Fellow ) of the Royal Society of Edinburgh . In 1868 Chevreul was accepted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences , in 1883 into the National Academy of Sciences .

On the occasion of his 101st birthday he was visited the evening before by photographer Nadar , the leading “wet plate photographer” at the time, which is considered to be the first photo report in history.

Up to his 102nd birthday he wrote articles and regularly attended meetings of the Académie des Sciences. He died in 1889 at the age of 102.

An overview of important academic stations

- 1824 Director of dyeing at the Royal Tapestry Manufactory

- 1830 Professor of Organic Chemistry at the National Museum of Natural History and

- 1860–1879 director of the National Museum of Natural History.

Important students of Chevreul

Scientific achievements

indigo

Chevreul isolated several plant dyes at the age of 20. Since no simple separation methods existed at that time, his work was associated with great effort. When heating indigo , he was able to detect indigo in pure form in the steam and in the subsequently resublimed solid, and also discovered the reduced, colorless form of indigo.

Chevreul salt

In 1812 Chevreul produced an interesting mixed - valent reddish copper compound, which is still named after him today, the Chevreul salt , CuSO 3 · Cu 2 SO 3 · 2H 2 O and is currently being further investigated using modern methods.

Fat chemistry

In 1811, Chevreul received a potassium soap made from lard to investigate. He treated the soap with acid and was able to isolate an acidic, mother-of-pearl-colored compound from it. He had isolated the first fatty acids and initially called them margarine (Greek: μαργαρίτηξ = pearl, margarine ), later also acid magarique and also acid stéarique ( stearic acid ). Chevreul isolated a second fatty acid, which he called acid oléique ( oleic acid ).

Chevreul later examined other fats: goose fat, cow butter, goat butter, sheep fat, jaguar fat and fats from dolphins. He discovered that there are solid (named by him: stearine (Greek : στέαρ = tallow)) and liquid ( élaine (Greek: λαιον = oil)) fats. He called the fatty acid obtained from goat cheese caproic acid (Latin: capra = goat), butyric acid from butter and lanolin (Latin: lana = wool) from wool fat . The isolated from the Delphi oil fatty acid he called Delphi acid , later as Phokäersäure . In the saponification of fats, a further by-product occurred in addition to the fatty acids. Even Carl Wilhelm Scheele had tasted this byproduct of saponification and found it sweet. Chevreul investigated the chemical bond between the fatty acid and the sweet substance (the chevreul glycérine ( glycerol ) called). Chevreul found that when fatty acids were converted into fats with glycerine, water was split off. After Louis Jacques Thénard , he named the bond between glycerine and fatty acids ether of the third order (the exact type of bond between the esters was still unknown at that time). In his work, Chevreul recognized the right relationships on which later chemists could build.

In addition to the fatty acids, in 1815 Chevreul found a fatty substance that could not be saponified. He called it cholestérine ( cholesterol ). He found no glycerine in Walrat , although it could also be saponified. He found a neutral substance which he called éthal ( cetyl alcohol ).

Business candles

Chevreul and Gay-Lussac had a patent for the production of stearic acid. With this patent, he and Gay-Lussac founded a candle factory in Paris. These new stearin-based candles did not develop any strong soot or toxic gases ( acrolein ) like the tallow candles used at the time .

Since the company was very small, it was initially unsuccessful. Adolphe de Milly, a student of Chevreul, and M. Motard bought Chevreul's patent and founded a very successful candle factory. These candles became one of the most important means of lighting for living spaces. The same applies to its use in polar expeditions of the 19th and early 20th centuries during the dark winter months. In memory of this achievement, the Chevreul cliffs in Antarctica bear his name.

Color theory

Alongside Newton Optics and Goethe's theory of colors , the work of Chevreul De la Loi du Contraste Simultané des Couleurs is considered to be one of the most important works on color theory. Chevreul developed a color wheel from the three primary colors red, yellow and blue, with 23 mixed colors for each primary color, so that a circle of 72 colors was created. He also developed colored bezels for successive lightening and darkening.

- Simultaneous contrast

If you put two very similarly colored fabrics or pieces of paper with slight deviations in brightness and shade directly next to each other, a strong color contrast arises for the viewer.

- Successive contrast

If you fix different colored surfaces individually, change the colored surface, the complementary color still has an effect on the eye.

By spatially juxtaposing pigments, he systematically determined the maximum simultaneous contrast and thus obtained a color series of opposing pairs. Today this is the range of school color boxes (DIN 5023). Through his main works he had a great influence on the development of the art industry and modern painting (including Georges Seurat ).

Great personality

His name was immortalized as an important personality on the Eiffel Tower , see: The 72 names on the Eiffel Tower .

Fonts

- Recherches chimiques sur plusieurs corps gras. Cinquième mémoire. The corps qu 'on a appelés adipocire. In: Ann. chim. Volume 95, (Paris) 1815, pp. 5-50. (To the discovery of cholesterol).

- About the présence de la cholésterine in the bile de l'homme. In: Mém. Mus. d'Hist. Nat. Volume 11, 1824. (With this font Chevreul coined the term "cholesterol").

- De La Loi Du Contraste Simultané Des Couleurs, Et De L'Assortiment Des Objets Colorés. Considéré D'Après Cette Loi Dans Ses Rapports Avec La Peinture, Les Tapisseries Des Gobelins, Les Tapisseries De Beauvais Pour Meubles, Les Tapis, La Mosaïque, Les Vitraux Colorées, L'Impression Des Étoffes, L'Imprimerie, L'Enluminure, La Décoration Des Édifices, L'Habillement Et L'Horticultur. Pitois-Levrault, Paris 1839.

- Des couleurs et de leurs application aux arts industriels à l'aide des cercles chromatiques. JB Baillière et fils libraires, Paris 1864.

literature

- Michel E. Chevreul: The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colors and their Applications to the Arts. With a special introduction and explanatory notes, by Faber Birren. Reinhold Publishing Corporation, New York NY et al. 1967 (also: Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York NY 1981, ISBN 0-442-21212-7 ).

- Claudia Gottmann: The portrait: Michel Eugene Chevreul (1786–1889 !!). In: Chemistry in Our Time . Vol. 13, No. 6, 1979, pp. 176-183, doi: 10.1002 / ciuz.19790130603 .

- William A. Smeaton: Michel Eugéne Chevreul (1786–1889): the doyen of French students Endeavor, New Series, Volume 13, No.2, 1989 (© Maxwell Pergamon Macmillian plc.)

- Christoph Johannes Häberle: Colors in Europe for the development of individual and collective color preferences. Dissertation. Wuppertal 1999, DNB 959797580 , pp. 36-43.

- A. Buchner (Ed.): New Repertory of Pharmacy. Volume XIV, Munich 1805, p. 149. (online in the Braunschweig digital library)

Web links

- Entry for Chevreul, Michel Eugene (1786-1889) in the Archives of the Royal Society , London

Individual evidence

- ↑ Michel-Eugène CHEVREUL - "pierfit" - Geneanet. In: geneanet.org. gw.geneanet.org, accessed November 22, 2016 .

- ^ Members of the previous academies. Michel Eugène Chevreul. Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences , accessed on March 7, 2015 .

- ↑ Member entry by Eugène Chevreul (with a link to an obituary) at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences , accessed on January 14, 2017.

- ↑ Holger Krahnke: The members of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen 1751-2001 (= Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Philological-Historical Class. Volume 3, Vol. 246 = Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Mathematical-Physical Class. Episode 3, vol. 50). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-525-82516-1 , p. 58.

- ^ Fellows Directory. Biographical Index: Former RSE Fellows 1783–2002. Royal Society of Edinburgh, accessed October 16, 2019 .

- ^ Hans Franke: Very old and very old. Causes and Problems of Old Age. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg etc. 1987 (= Understandable Science. Volume 118), ISBN 3-540-18260-8 , p. 94 f.

- ↑ Electronic Spectra of Chevreul's Salts. In: J. Braz. Chem. Soc., Vol.13 no.5 São Paulo Sept. Oct. 2002, accessed July 19, 2014.

- ↑ Axel W. Bauer : Cholesterol. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin and New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , pp. 258 f .; here: p. 258.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Chevreul, Eugène |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Chevreul, Michel Eugène (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French chemist and the founder of the modern theory of pigments |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 31, 1786 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Angers , France |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 9, 1889 |

| Place of death | Paris |