Minbar

Minbar ( Arabic منبر, Plural manabir /منابر / manābir ) is the pulpit in the mosque , usually built next to the mihrāb prayer niche on the qibla wall, on which the chatīb (خطيب) preaches the sermon ( Chutba ) on Friday . In the past, the decrees of the respective rulers were also announced from the pulpit. Theodor Nöldeke has already pointed out the possibility that the term was originally a loan word from Ethiopian .

History and function of the minbar

The origins of the minbar go back to the time of the Prophet Mohammed , who, according to tradition, had two steps with a seat built from palm trunks so that his believers could see him better. It was called aʿwād (plural of ʿūd; wood). Among the Islamic historians, al-Wāqidī reports in the world history of at-Tabarī about the establishment of a “pulpit” at the time of Muhammad: “In that year (7/628) the Prophet made himself minbar on which he preached to the people used to make two steps and his seat (maq'ad). According to another version, it was made in 8/629, and we consider that to be safe ” . The minbar was used in the same way by the first caliphs . Initially, the minbar was seen as the seat of the ruler and a symbol of worldly power.

Not all mosques originally had a pulpit; the Egyptian local historian al-Kindi al-Misri († 971) reports in the 10th century on the extensive expansion work of the great mosque in Fustāt under the famous tax administrator Qurra ibn Sharik , who installed the pulpit in 94 (i.e. between 712 and 713) Had a mosque erected. Until the time of al-Kindi it was the second oldest pulpit in the provincial cities after the prophet minbar in Medina: “He (di Qurra ibn Sharik) set up the new minbar in 94 (corresponds to: 712-713). It is said that to this day in no administrative area has an older pulpit known than this - apart from the Prophetenminbar. ” According to an old report, handed down in a papyrus roll (Heidelberg University), there is said to be a minbar in Fustat around 658-659 which was used as the seat of the provincial administration in his speeches in the profane area.

The first Umayyad caliph , Muʿāwiya b. Abī Sufyan , brought his own minbar with him on his journey from Damascus to Mecca . So the first minbars were mobile. The city chronicler of Mecca al-Azraqī († 865) reports that Muʿāwiya was the first to have given the Friday sermon in Mecca from this minbar, which had only three steps. According to Andalusian historians, the minbar of the Umayyad al-Hakam II was also movable and could be pushed on wheels after the completion of the main mosque of Córdoba in 965-966. The Abbasid caliph al-Wāṯiq (ruled between 842 and 847) gave the order to set up a pulpit at three important stations of the pilgrimage ( hadj ) - Mecca, Mina and ʿArafāt . As can be read in al-Azraqi, these were used for cultic purposes in the pilgrimage ritual, since a sermon is held at all stations.

But even beyond the Umayyad period, a minbar was also used as a judge's seat, which the judge himself had set up in front of his house in order to pronounce judgments from there. This use of the minbar can be traced back to the 10th century in Kairouan . In this case, the pulpit as a facility for conducting public-law business is detached from the minbar of the mosque and is the private property of the judge in the secular area. The use of the minbar for purely cultic purposes in the mosque can only be observed under the Abbasids . "With the development of the mosque into an exclusive cult building, the mimbar, the throne of the theocratic ruler, becomes the pulpit" .

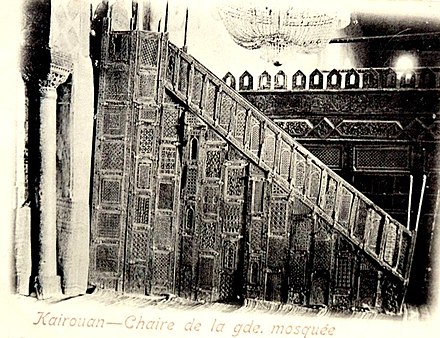

The archaic form of the minbar as part of the Islamic sacred building is preserved in the original in the main mosque of Kairouan, built by the Aghlabid ruler Abū Ishāq Ibrāhīm II (up to 902) from cedar wood, which was delivered directly from Baghdad for this purpose . This eleven-step pulpit still lacks the distinctive structure of the later wooden minbars, because the entrance gate and the roof attachment are missing. The entire ornamentation is Umayyad (see also: Kairouan ).

The final shape of the pulpit, as it appears in the Al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem , was already formed during the Fatimids . Nūr ad-Dīn donated it to the mosque of Aleppo in 1168 and it was brought to Jerusalem by Saladin . This minbar already has a frame gate and a dome housing to top it off. The minbar in the mosque and madrasa of Sulṭān Ḥasan (1354–1361) in Cairo - now made of stone - is designed in a similar way.

Another example of Fatimid art of the pulpit design with its frame system and the tendril filling in Syrian-Egyptian style is in the ʿAmr Mosque in Qus in Upper Egypt قوص / َ Qūṣ received. The minbar and mihrab form an interior design unit here and were a gift from the Fatimid wezir and governor of Aswan and Qus Talāʾiʿ ibn Ruzzīqطلائع بن رزيق / Ṭalāʾiʿ b. Ruzzīq to the city in 1155.

The pulpit of the prophets in Medina as a place of the oath

Of course, the minbar of the Prophet in Medina occupies a special position among the minbars in the Islamic world . Taking the oath at the prophet's minbar has a special status in the course of reaching a judgment: a perjury performed next to or on the prophet's minbar leads to hell. A prophetic saying that is quoted several times in the relevant hadith collections has a normative character in this sense:

- "The one who perjuries in my pulpit (minbarī) takes his place in hellfire".

The warning of the punishment with hellfire “... (he) takes his place in hellfire” is an old motif used in similar contexts in hadith literature. The oldest work that records this alleged prophecy is the legal work of the scholar Mālik ibn Anas ; As a comment, it says that the defendant's request to take the oath at the Prophet's minbar has been legal practice since the beginning of Islam. According to Islamic traditions, the Prophet Mohammed is said to have canonized the oath in his pulpit on legal issues as a Sunna . However, research today assumes that the Prophet's Minbar in Medina was not yet one of the holy places during Muhammad's lifetime - such as the Kaaba in Mecca , where the oath was also taken. Because the oldest document from the early days, the so-called " Municipal Code of Medina ", only mentions the settlement of Yathrib as "holy" and "inviolable" ( haram ), but not a special place, or even the Minbar itself The pulpit, at which one has to take the oath par excellence in Medina, is of later origin than its erection. The pulpit gradually developed into the " platform for the discussion of all public affairs" ( Ignaz Goldziher ). It was initially a kind of “judge's chair”, the generally known place of residence of Muhammad outside of prayer times - as Carl Heinrich Becker aptly describes in his study. The pulpit was thus understood in the early days as a symbol of secular, political power; it is the place for the fulfillment and confirmation of political legitimation. When the first caliph Abū Bakr was elected, he was asked to go to the pulpit so that the people would swear allegiance to him - it says in the description of the event at Bukhari ; at Ahmad ibn Hanbal - in his "Musnad" it says: "When the people had gathered, Abu Bakr climbed onto the pulpit (minbar), onto something that had been made for him, whereupon he gave the speech". Even with the Prophetenminbar, it is not the building itself or its shape or size that is decisive, but the place itself where one takes the oath or receives political legitimation.

The function of the minbar in Medina and later in the provincial cities as a place of public life and the taking of the oath in legal decisions was originally not understood as a parallel to the Meccan sanctuary, where taking the oath was already a custom in pre-Islamic times. The alignment of both places - the Kaaba in Mecca, the prophet's pulpit in Medina - only takes place in the attempts at systematization of early jurisprudence in the time of Malik ibn Anas and aš-Šāfiʿī in the late 8th century. Because of the way in which the law was found, the Prophetenminbar was called the "arbitration board " of the law maqta 'al-huquq /مقطع الحقوق / maqṭaʿu ʾl-ḥuqūq (see Lit.Dozy); In the great mosques of the Islamic empire - Damascus , Kufa , Fustāt , Córdoba - the proximity of the mihrāb was considered to be the place of the oath. According to a fatwa from Qairawān , which the Moroccan scholar al-Wanscharīsī (* 1439; † 1508) quotes in his collection of North African legal opinions, the oath of the Koran (muṣḥaf) can be taken in the main mosque of Sūsa .

The Islamic jurisprudence of the 9th century, however, held the oath taking at the minbars of simple mosques ineffective: "Nobody is called to take the oath in the mosques of the Bedouins, neither because of a quarter of the country nor for less". Such a legal conception - the distinction between mosques located in the quarters of certain tribes and those of the city dwellers - could flourish in accordance with social distinctions between sedentary people and Bedouins.

The Prophetenminbar in Medina remained inviolable as a relic from the early days to the present; According to the sources, this idea was part of the Islamic tradition as early as the first Muslim century ( 7th century AD). The Umayyad caliphs - Muʿāwiya, ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān and al-Walīd ibn ʿAbd al-Malik are said to have intended to take the pulpit with them to Damascus in order to emphasize the political power in the new residence of the Umayyad caliphs. Muʿāwiya was able to be deterred from his undoubtedly politically motivated project, but had the pulpit of Medina wrapped in its original place with a fabric - an act whereby an object, as depicted by Julius Wellhausen and after him by CH Becker, attains a certain sacredness and which was already common at the Kaaba in Mecca in pre-Islamic times.

The fact that there were reservations about making the Prophet's minbar a taboo is shown by the statements in the form of hadiths traced back to the Prophet in the middle of the 8th century : "God, keep me from worshiping my grave as an idol and my pulpit from being feasted used"

In Mecca , the place of oath par excellence is the Kaaba , although it does not have a minbar; the oath is taken there between the corner with the black stone and the maqam Ibrahim: (baina r-rukn wa-ʾl-maqām). At the latest at the beginning of the 8th century, Meccan scholars determined, according to the local historian al-Azraqi, that the taking of the oath for trivial matters is not allowed here, which should emphasize the sanctity of the place.

literature

- Carl Heinrich Becker : The pulpit in the cult of old Islam . In: Carl Bezold (Ed.): Oriental Studies. Dedicated to Th. Nöldeke on his seventieth birthday (March 2, 1906). Gieszen, 1906. Vol. IS 331-51. Also in: Islam Studies . Volume IS 450 ff. Leipzig 1924

- Heribert Busse : The pulpit of the prophet in the paradise garden. In: Axel Havemann, Baber Johansen : Present and History. Islamic Studies. Fritz Steppat on his sixty-fifth birthday. Brill, Leiden 1988, pp. 99-111.

- Reinhart Dozy : Supplément aux Dictionnaires Arabes , 3rd edition. Vol. II.347b: maqṭaʿ . Brill, Leiden 1967

- Maribel Fierro: The mobile Minbar in Cordoba: how the Umayyads of al-Andalus claimed the inheritance of the Prophet. In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam (JSAI), Vol. 33 (2007), pp. 149–168.

- J.-Cl. Garcin: In: Ars Islamica , Vol. 9 (1970), p. 115 (Qus)

- Ignaz Goldziher : The Chatīb among the Arabs . In: Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes 6 (1892) 90-102

- Miklós Murányi : “man ḥalafa ʿalā minbarī āṯiman…”. Comments on an early traditional item . In: Die Welt des Orients 18 (1987) 92-131; 20/21 (1989–1990) 115-120 (supplements)

- J. Pedersen : The oath among the Semites . Strasbourg 1914

- Julius Wellhausen : Remains of Arab paganism . (Reprint), Berlin 1961

- Ferdinand Wüstenfeld (ed.): The chronicles of the city of Mecca . Vol. I. The history and description of the city of Mecca by al-Azraqi. Leipzig 1858. Reprint Beirut 1964

- The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Vol. VII.73 (minbar)

- The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Vol. V.514 (Qus)

- al-mausūʿa al-fiqhiyya . 2nd Edition. Kuwait 2005. Vol. 39, pp. 84-88

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ New contributions to Semitic linguistics . Strasbourg 1910. p. 49

- ↑ Maribel Fierro (2007), p. 156

- ^ CH Becker (1924). P. 453 (translation: CH Becker).

- ↑ Maribel Fierro (2007), p. 160

- ^ Fuat Sezgin: History of Arabic literature. Vol. 1, p. 358. Brill, Leiden 1967

- ↑ Miklós Murányi (1987), p. 114 and note 68; CH Becker: Islam Studies , Vol. 1, p. 458

- ↑ Raif Georges Khoury: ʿAbd Allāh ibn Lahīʿa (97-174 / 715-790). Juge et grand maître de l'école egyptienne. Avec édition critique de l'unique rouleau de papyrus arabe conservé à Heidelberg. Wiesbaden 1986. p. 285 (comment); M. Muranyi (1987), p. 114. Note 68

- ↑ Maribel Fierro (2007), p. 153

- ↑ M. Muranyi (1987), p. 110, note 62

- ^ CH Becker: On the history of the Islamic cult . In: Der Islam 3 (1913), p. 393; CH Becker (1924), p. 345

- ↑ About him see: The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Brill, suffering. Vol. 10, p. 149

- ↑ M. Muranyi, (1987), pp. 93-97 after Sahnūn ibn Saʿīd , ʿAbdallāh ibn Wahb and Mālik ibn Anas with traditional variants; Pp. 98–99, notes 19-30 with further evidence; see also p. 103 and note 46; al-mausūʿa al-fiqhiyya . 2nd Edition. Kuwait 2005. Vol. 39, p. 88

- ↑ M. Muranyi (1987), p. 109 and note 60

- ^ In: Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes (WZfKM) 6 (1892), p. 100; M. Muranyi (1987), p. 110 and note 62

- ↑ M. Muranyi (1987), p. 111 and note 63: “Possibly this is not the minbar of the Prophet, but a small and provisional building specially erected for Abu Bakr's ḫuṭba. Also with the Prophetenminbar it is not the building itself and its size or shape that is decisive, but the place itself where the oath is taken. " ; see also ibid. note 64: the homage to Abu Bakr was confirmed by taking an oath at the minbar

- ↑ M. Muranyi (1987), pp. 109-112

- ↑ Miʿyār al-muʿrib (Beirut 1981), Volume 3, p. 159

- ↑ On the question see: GE von Grünebaum: Der Islam im Mittelalter (Zurich / Stuttgart 1963), pp. 222ff and 518-519; M. Muranyi (1987), p. 112. Note 66.

- ↑ M. Muranyi (1987), pp. 117-118 and note 72

- ↑ CH Becker (1906), p. 343

- ↑ M. Muranyi (1987), p. 130 and note 88 according to: ʿAbd ar-Razzāq aṣ-Ṣanʿānī : al-Muṣannaf, VIII. No. 15916.

- ↑ MJ Kister: Maqām Ibrāhīm . In: Le Muséon 84 (1971), p. 482