North Carolina Algonquin

The North Carolina Algonquians were a group of culturally related Indian tribes and lived on the coast of what is now North Carolina in the eastern United States at the beginning of the 17th century . They were among the southernmost tribes of the Algonquin language group, but their language is no longer spoken today. They have been considered extinct since 1915. Their neighbors to the north were the Virginia-Algonquin across the Dismal Swamp , which formed an almost impenetrable border. Both tribal groups had a similar culture and are grouped under the term Southeast Algonquin .

language

There is little evidence of the linguistic proximity of the coastal tribes in North Carolina to the Algonquin language family. In addition to place and tribal names, fewer than 100 words have been written down and handed down by English colonists . Presumably they come from Roanoke , Croatoan and Secotan dialects. There are also 37 other traditional words from the Pamlico language. Both lists of words are sufficient for an assignment to the Algonquin language family. The affiliation of other tribes is not sufficiently secured. It is very likely that the Weapemeoc and Chowanoke tribes were Algonquin, while the Moratuc and Neusiok could also have been Iroquois . The Pomouik were apparently identical to the Pamlico.

Residential area and environment

Iroquois tribes lived in the west and south of the North Carolina Algonquin, but the boundary between these peoples is indefinite. The Tuscarora, for example, claimed the area west of the Chowan River and south of the Cuttawhiskie Swamps in the 17th century . Around 1585, however, there was evidence that Algonquin villages were also in this area.

In the very flat coastal plain of North Carolina there are numerous lakes, extensive swamps and sand dunes. The coastline consists of deeply carved bays like the Currituck , Albemarle and Pamlico Sound and tidal currents . In front of the land are the Outer Banks , a chain of very narrow dune islands and sandbanks that form a barrier between the Atlantic and the mainland. The predominantly sandy soil is covered by hard grass, swamp vegetation and evergreen forests. The climate is humid and subtropical and leads to an annual growth period of around 250 days. In addition to various salt and freshwater fish, oysters , edible mussels , sea turtles and American alligators also live in rivers, lakes and on the coast. In the coastal plain there are numerous species of water birds, such as ducks and geese , as well as mammals such as deer , foxes , squirrels , possums , rabbits , beavers and, in earlier times, bears and pumas .

North Carolina Algonquin tribes

When the first European, Giovanni da Verrazzano , reached the region in 1524 in search of a passage to the Pacific , it was very likely that he met members of the Algonquin tribes living there, although there is no evidence of this. Traditions of the natives from the time of the English colony on Roanoke Island indicate a single early contact with whites: In 1558, Spanish castaways were rescued by residents from Secotan and after a short time sent home on a makeshift ship. The Indians bought iron tools from other ships whose wrecks were stranded on the North Carolina coast. For most of the Indian groups in the coastal area of North Carolina, the history of European contacts only began with the arrival of English ships in 1584 and the establishment of a colony in the following year, when a group of 110 people settled the island of Roanoke.

Villages and tribes around 1585/86

|

|

|

Villages and tribes 1657–1795

| Village | tribe | residential area |

|---|---|---|

| Radauquaquank (1708) | Bear River | Pamlico Sound |

| Chowan Indian Town (1708–1795) | Chawanoke | Chowan River |

| Katoking (1657) | Chawanoke | Chowan River |

| Rickahock (1657) | Chawanoke | Chowan River |

| Wohanock (1657) | Chawanoke | Chowan River |

| Cape Hatteras Indian Town (1708–1788) | Hatteras | Cape Hatteras |

| Mattamuskeet (1733) | Machapunga | Lake Mattamuskeet |

| Chatooka (1708-1712) | Neusiok | Neuse River |

| Rouconk (1708-1712) | Neusiok | Neuse River |

| Pamlico (1708) | Pamlico | Pamlico River |

| Paspatank (1708) | Paspatank | Pasquotank River |

| Poteskeet (1708-1733) | Potencies | Currituck Sound |

| Yeopim (1696-1733) | Weapemeoc | North River (North Carolina) |

The years in brackets correspond to periods in which the villages were verifiably inhabited.

Demographics

Little information is available about population figures in the late 16th century. The largest tribe the English came across were believed to be the Chawanoke. They inhabited 18 villages with a total population of around 2,500 people. The total number of all North Carolina Algonquins is believed to have been about 7,000 or more by 1585. The population density was certainly higher along the rivers than on the sound or on the islands. Information about tribal borders is sparse, and Europeans have often considered allied but independent groups to be one and the same tribe. This is especially true of the Roanoke, Croatoan and Secotan, whose tribal boundaries with their Iroquois neighbors are indefinite. Imported European diseases led to high mortality among the Indians in the region and the premature depopulation of entire areas. Diseases such as measles , smallpox and even colds resulted in a death rate of over 25 percent in some villages. Loss of people through wars against the colonists, on the other hand, was small, in contrast to conflicts between individual tribes.

North Carolina Algonquin Population (Estimated)

| tribe | 1709 1 | 1709 2 | 1733 | 1755 | Last mention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potencies | 100 | 75 | 1733 | ||

| Paspatank | 35 | 25th | 1709 | ||

| Weapemeoc | 20th | 15th | 1733 | ||

| Chawanoke | 50 | 38 | 7th | 1796 | |

| Roanoke | 1763 | ||||

| Hatteras | 53 | 40 | 6-8 | 8-10 | 1788 |

| Machapunga | 100 | 75 | 8-10 | 1915 | |

| Pamlico | 50 | 38 | 1709 | ||

| Bear River | 165 | 125 | 1712 | ||

| Neusiok | 50 | 38 | 1712 | ||

| All in all | 621 | 469 |

1 The population figures for the English explorer John Lawson refer to warriors. The actual population was extrapolated in a ratio of 3:10.

2 Lawson, however, recommended a ratio of 2: 5.

Culture in the 16th century

Livelihoods

In addition to hunting and fishing, horticulture and the gathering of wild herbs were important, with no information on the ranking. The cultivation of maize was widespread and the basis of sedentary life in the villages. Maize was planted from late March to early July after the weeds had been weeded in the fields with wooden hoes. The work was done by women and men alike. With plant sticks they bored holes in the ground about 90 cm apart, in each of which four kernels of corn were placed and covered with earth. No fertilizer was used. The corn harvest took place from July to September. In addition, the Indians cultivated two types of beans , two types of cucumbers and pumpkins , sunflowers , goosefoot (Chenopodium) and foxtail (Amaranthus) in sometimes fenced off fields. The tobacco always occurred on separate fields. The long growing season of 240 days often allowed two harvests a year from the same field.

Spring was the time of fishing and shell-collecting. Fish were caught with weirs and structures made of reed in rivers and estuaries, as well as with spears from canoes or in shallow water. At night fish were lured to the boats by fire and caught with nets. Birds and mammals were hunted with bows and arrows, and snakes and turtles were prey in the swamps . Bears were driven into the trees to kill. In autumn the Indians gathered roots, nuts and berries in the forests. Dogs were kept as pets and occasionally consumed.

To prepare meals, the Indians cooked or fried fish, meat and corn separately or mixed in a clay pot. Flour for baking bread was made from corn, beans, sunflower seeds, chestnuts, acorns, chinquapine and hazelnuts. Pumpkins, peanuts and roots were eaten raw or cooked, while the rhizomes of Peltandra virginica had to be detoxified by boiling before consumption. The seeds of Chenopodium and Amaranthus species were used to make a tasty porridge and the stems of these species of plants were burned to serve as a salt substitute. How food was stored and preserved is not known.

Materials management

Tools were often made of shells, bones and wood, more rarely of stone because there was a lack of them. Trees were felled through controlled burning over the roots and worked with scraping tools. The Indians used oil to tan hides. Women made pots out of clay, crushed shells, sand or fine gravel, which were decorated with individual patterns and embossing. The round pots had a pointed or semicircular bottom that was stuck into a mound of earth. They also made baskets and mats from cane and other vegetable, fibrous materials.

There were scrapers and knives made of seashells, picks and chisels made of stone, and wooden picks. The weapons included saber-shaped clubs made of wood, about one meter long, which were additionally armed with antler shoots. Bows were made of maple or hazelnut branches and the arrows were made of reed with a tip made of shells, stone or a fish tooth. Occasionally the arrowheads were poisoned. Spears had shafts made of wood or reed, were pointed at one end or had the tail of a king crab as a spear tip.

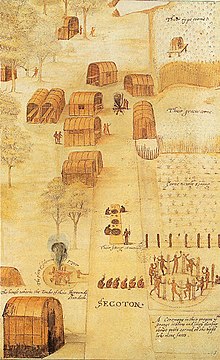

The ten to thirty houses in a village were either grouped around a central square and surrounded by wooden palisades or stood individually between the corn fields. They were usually located on a river or pond, which was sometimes specially created. The houses were rectangular with rounded roofs made of curved poles. These were tied together at the apex, stabilized with crossbars and covered with bark, rush mats and twigs. The covering could be moved to let in light. Usually the houses were about 11 to 14 m long and only had one room. However, there were also houses of 22 m in length, which were divided into several rooms. Raised platforms along the walls were used for sleeping. Chiefs' houses and temples were larger, but resembled normal houses in shape and construction. The temple in the village of Pomeiooc was depicted with an unusual roof.

The social status was recognizable by the clothing. In the summer, men and women sometimes wore no clothes at all or only a loincloth . Another popular item of clothing was a leather or rabbit fur cloak tied over one or both shoulders and belted. The fur was carried inwards towards the body. Often the clothing was decorated with fringes and, in the upper classes, decorated with pearls and painted. Little girls covered their genitals with a pad of moss or bark. To protect the warriors, there were wooden breastplates and a shield made of bark.

Women wore their hair fringed on their foreheads, with or without headbands, and tied in a bun at the nape of the neck or open to the shoulders. The men had a topknot on the back of their necks and priests had a comb on their head. Men adorned themselves with paint on their skin, while women tattooed their bodies and faces. Both sexes preferred necklaces and earrings made of bones and shells. Men often wore a headdress made of feathers, copper and shells, which indicated the rank of the wearer. Young men plucked their scanty whiskers, while older men grew thin beards.

Dugout canoes that could carry up to 20 people and were moved forward by paddling or staking were widely used. For the transport there were special carrying baskets with straps over the shoulder, as well as quivers made of rush for the arrows of the archers.

Social organization

The household was a kind of extended family and was considered the smallest unit of the North Carolina Algonquin. It consisted of an average of 10 members and several households formed a village, while each tribe could consist of one to eighteen villages. Above the tribal level there was the so-called confederation , a loose alliance of several tribes. As with its northern neighbors, the North Carolina coastal area was also very diverse. The upper class consisted of the chief, his family and relatives, as well as his advisors and probably also the priests. They had certain privileges, such as trade monopolies, and were therefore able to enjoy a certain level of prosperity, and could be recognized by their clothing and special jewelry. Jurisprudence and political decisions were reserved for the council assembly, which consisted of members of the upper class. With Weroance or Werowance the tribal chief and other socially high people were referred to.

Most wars were fought in retaliation. The fighting often began with an ambush attack and was fought at dawn or at night by moonlight. Usually the defeated men were killed, while women and children were spared and taken into their own tribe.

religion

The North Carolina Algonquians believed in gods and spirits, which they called Montoac . The Indians imagined the gods as human figures. Kewas were the names of statues of gods carved out of wood, which were erected in the temples inhabited by priests. Besides the priests, there were sorcerers or seers, whom the English called conjurors . The Algonquians believed in the afterlife, with good and bad people treated differently. Evil people fell into a fire hole beyond the western horizon after death. The belief in rebirth was firmly anchored in religion.

Among the most important ceremonies that belonged Green Corn Festival (Engl. Green corn festival), was thrown in the tobacco into the air, into the water or into the fire. These actions were accompanied by prescribed gestures and sounds. In the case of serious illnesses, a healer was called in to suck the pathogen out of the body. Other treatment methods consisted of the use of medicinal plants and healing earth .

Typically, a dead person was buried in a grave about 90 cm (three feet ) deep, while the upper class dead member received other treatment. His body was skinned, the flesh scraped from the bones and then re-covered with the original skin and stuffed. He was then wrapped in a mat and placed on a scaffold in the temple. He received dried meat as an addition.

Dances were popular with men and women alike. The songs sung to it were accompanied by shaking the pumpkin rattles filled with fruit pits. Shortly after the establishment of the Roanoke colony, European toy rattles began to appear among the Indians.

history

First contact with English colonists

British captains and explorers Philip Armadas and Arthur Barlowe followed the Florida coast north in 1584 and reached the islands on the coast of what is now North Carolina. They officially took possession of the area for the English Crown and named it Virginia in honor of their Queen . They followed the Doctrine of Discovery . This legal fiction held that areas in North and South America were legally owned by the European nations who first discovered and claimed them. The ownership claims of the natives were completely disregarded.

The first contacts between the English and Secotan came about, which at first went harmoniously. Captain Barlowe later made an enthusiastic report in London. A year later, Captain Sir Richard Grenville reached the Outer Banks of North Carolina and founded the first British colony in North America on the island of Roanoke. As governor was Ralph Lane appointed. After their food supplies were depleted, they relied on the hospitality of the Indians. Their generosity, however, ended when they themselves ran out of food. Conflicts arose, the colonists burned the village of Aquascogoc and killed the chief.

In June 1586, Admiral Sir Francis Drake appeared with his fleet off Roanoke and brought the surviving colonists back to England. A little later, a supply ship under Captain Grenville with new emigrants reached the now abandoned settlement. He left 15 volunteers with supplies for two years on the island so that the English claims to the land would not be lost. In May 1587 an English ship under Captain John White, who had been one of the first settlers in 1585, reached Roanoke Island with another 150 settlers and found the colony abandoned. On August 25, White left for England to take care of supplies.

The outbreak of the Anglo-Spanish war prevented an early return to America. White did not return to Roanoke until 1590. He found the colony destroyed and there was no trace of the remaining 90 men, 17 women and 11 children. The fate of these colonists remains in the dark. Apparently they left the island in 1587 and moved to the Croatoan. However, records of the Virginia colonists after 1607 indicate that they may later moved further west or north separately. It is not known what lasting effect their permanent presence in the North Carolina coastal area may have had on the Indians.

Interethnic contacts between white colonists and Indians were mostly made on a personal level and were apparently limited to upper class Indians. Reasons for such contacts were trade, politics, the colonists' search for geographical knowledge and the exchange of information about the respective culture and religion. The contacts on both sides were limited to a small number of people because they had to speak both languages. This included two Indians who were taken to England in 1584 and later returned to Roanoke. The Roanoke Indians suspected that the whites had supernatural powers and were increasingly disappointed by the colonists. On the other hand, a pro-English group formed among the Indians who hoped for profit through trade and alliances with the whites. However, this attitude weakened old alliances between the Indian tribes. The alliance between Croatoan and Roanoke fell apart after the Croatoan sided with the English. Part of the Weapemeoc followed the advice of the Chawanoke to neutrality, while the rest of the tribe allied with the Roanoke. Most of the Algonquin tribes in the area were often involved in wars with the Tuscarora.

17th-19th century

After the failure of the first Roanoke colony, it took around 120 years for the English to re-establish a colony in the North Carolina area. As a result, the indigenous population continued to decline. The main reasons for this were the diseases brought in by Europeans, but also various wars with the Iroquois neighbors. In 1696, a large Pamlico mortality is reported. In the course of the Tuscarora War of 1711–1713 against the white colonists, more Algonquian allies than Tuscarora died or were sold into slavery . By 1709 there were only around 600 Algonquians left in North Carolina and by the end of the century only a small remnant lived. The dwindling number was accompanied by significant losses of tribal land. In the case of land sales, the Indians were generally taken advantage of by the whites. For example, between 1660 and 1662 the Weapomeoc sold their land on Albemarle Sound before moving further inland. In 1697 they complained of constant attacks by white settlers in their new residential area. Around 1700 the Chawanoke were assigned a reservation of 31 km at Bennet Creek , which the authorities reduced to half in 1707. In 1713 the rest of the land was sold by the tribe. After the end of the Tuscarora War, the colonial authorities also assigned the Machapunga a reservation. Other Algonquin groups at Pamlico Sound joined the Machapunga or Tuscarora.

In the 17th century the Chawanoke had frequent contact with their northern Algonquin neighbors in Virginia. The traditional hostility to the Tuscarora persisted among some tribes even during the war against the whites. In contrast, the Machapunga and other tribes at Pamlico Sound changed their alliances. Before 1700 they were still at war against the Tuscarora and Coree , in 1711 they fought alongside them against the English. The Hatteras, Weapemeoc, Paspatank and Poteskeit were allied with the English in the Tuscarora War. The Hatteras' friendly demeanor was evidently due to the fact that they had numerous white ancestors.

Aside from the Tuscarora War, there are hardly any known open conflicts between the Algonquin and colonists in North Carolina. Around 1700, the sale of alcohol to the Indians created a major problem. As a result, the sale of alcohol to Indians was banned from 1703, but prohibition was never rigorously enforced. Although the native language was replaced by English in the 18th century, very little was done to educate the Indians. In the 17th and 18th centuries, some Indians were baptized by Anglican clergymen and given English names. Due to the lack of white doctors, Native American healers were often called in for help and were able to make money by curing white settlers. There are no reliable figures on the number of Indian servants and slaves.

The Tuscarora War led to famine among many Algonquin tribes. The English destroyed the maize fields of the Machapunga and their allies, while the Hatteras were prevented from tilling their gardens and fields. They had to be supplied with food by the colonial authorities in 1714 and 1715.

In the 18th century, more and more products of European origin came to eastern North Carolina. The Indian bows and arrows were replaced by rifles and the wooden clubs by axes and hatchets made of iron. The traditional Indian costume disappeared and was replaced by English clothing. The chief of the Roanoke had a house built in the English style in 1654. Only the baskets of the coastal Indians made of rush and silk grass with woven motifs were still popular.

First cousin marriages were forbidden by law, forcing them to marry into other tribes. The Algonquians had the Huskenaw rite , which was considered a kind of initiation of boys and girls in puberty . It took place regularly in December and lasted five to six weeks. During this time the young people stayed in a special building outside the village. Circumcision has been practiced in two out of fifty Machapunga families , but details are not known.

As late as 1700, the North Carolina Algonquin had an intact political organization with hereditary chieftainship. The bodies of dead chiefs were stored in the temples as in earlier times. Wealthy tribal members were allowed to purchase this right. Shell necklaces called wampum served as money and could be paid as reparation for crimes, for example.

20th century

All of the North Carolina Algonquins are now considered extinct. As the number decreased, interest in these tribes was completely lost in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In 1916, the American anthropologist Frank G. Speck tried to track down descendants of the local Algonquin. His research yielded the last published report on this ethnic group. Speck's small collection of material on the Machapunga is in the American Museum of Natural History in New York .

In the 1915 census , around 100 people of Native American descent were counted on Roanoke Island. There were also some people on the neighboring Sand Islands , as well as on the mainland in Dare and Hyde Counties . Frank G. Speck identified them as descendants of the Machapunga, who mostly mixed with blacks, but also with whites. They lived by hunting and fishing and supplemented by agriculture and animal husbandry. They collected leaves of holly -Art Ilex vomitoria , to use as a tea. Many traditional indigenous products were gradually replaced by white products. Only fishing nets with different mesh sizes for different fish species were still made from the fibers of the Asclepias syracia .

In 1948, William Harlen Gilbert referred to the Vices Tribe , another mixed blood group that lived near Hertford in Perquimans County . However, their relationship to earlier Algonquin tribes has not been proven.

See also

List of North American Indian tribes

literature

- Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians . Vol. 15: Northeast. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC 1978. ISBN 0-16004-575-4 .

- Wilcomb E. Washburn (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians . Vol. 4: History of Indian-White Relations. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC 1988. ISBN 0-16004-583-5 .

- Alvin M. Josephy Jr.: 500 Nations. Frederking & Thaler GmbH, Munich 1996. ISBN 3-89405-356-9 .

- Alvin M. Josephy Jr.: The world of the Indians. Frederking & Thaler GmbH, Munich 1994. ISBN 3-89405-331-3 .

- Klaus Harpprecht / Thomas Höpker: America - The history of the conquest from Florida to Canada , GEO im Verlag, 1986. ISBN 3-570-07996-1 .

- Siegfried Augustin : The history of the Indians. From Pocahontas to Geronimo. Nymphenburger, Munich 1995. ISBN 3-485-00736-6 .

- Urs Bitterli : The discovery of America. From Columbus to Alexander von Humboldt. Verlag CH Beck, Munich, 1992. ISBN 3-406-35467-X .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15. Northeast. Christian F. Feest : North Carolina Algonquians , 272.

- ↑ a b c d Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15. Northeast. Christian Feest: North Carolina Algonquians , 271.

- ↑ a b c Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15. Northeast. Christian Feest: North Carolina Algonquians , 272.

- ↑ Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15. Northeast. Christian Feest: North Carolina Algonquians , 280.

- ↑ a b c Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15. Northeast. Christian Feest: North Carolina Algonquians , 273.

- ↑ a b c d e f Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15. Northeast. Christian Feest: North Carolina Algonquians , 275-276.

- ↑ a b Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15. Northeast. Christian Feest: North Carolina Algonquians , 277.

- ↑ a b c d Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15. Northeast. Christian Feest: North Carolina Algonquians , 278-279.

- ^ A b Alvin M. Josephy jr .: 500 Nations. Frederking & Thaler GmbH, pages 186-187.

- ^ A b c Klaus Harpprecht / Thomas Höpker: America - The history of the conquest from Florida to Canada , page 154–157

- ↑ Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15. Northeast. Christian Feest: North Carolina Algonquians , 271-272.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15. Northeast. Christian Feest: North Carolina Algonquians , 279-280.