Oppidum d'Ensérune

The former oppidum d'Ensérune , located on a steep hill extending from east to west, is a typical example of the settlement sites that were particularly popular with the Gauls (Celts) of southern France during the Iron Age .

The oldest settlement (Ensérune I) consisted of dwellings scattered on the hill, which date back to the middle of the 6th century BC. To be dated. Towards the end of the 5th century BC These modest dwellings were replaced by houses built in rows along long streets, most of which consisted of just one rectangular room with an underground silo or dolium . This first fortified city (Ensérune II) was at the highest point of the hill, while its necropolis with cremation graves extended at its lower western end . Two centuries later, the city expanded to the southern flank, where its cemetery was originally located.

In the 2nd century BC The city and its fortifications expanded further to the west (Ensérune III), until in the 1st century even the former necropolis on the southern flank was built over with a new quarter, where the influences of the Greco-Roman tradition can be seen can. Their houses were significantly larger and at that time often - based on the Roman model - consisted of a central courtyard; the atrium , grouped rooms that were decorated with mosaics and plaster paintings.

Ensérune knew how to use the cultural influences of the region and, as an active trading center, benefited from the increasing volume of trade throughout the Mediterranean.

It was not until the first century AD that people gradually left the oppidum to settle in the villas of the lowlands.

The archaeological museum central location holds the most important collection of Attic vases of southern France and the largest collection of Iron Age grave goods of the Languedoc .

An exceptional location

The remains of the former oppidum d'Ensérune crown a 650-meter-long plateau, about 120 meters above the surrounding flat plain. It is located about 9 kilometers southwest of the city center of Béziers , 17 kilometers northeast of Narbonne , and 3 kilometers north of Nissan-lez-Enserune . The Mediterranean beach stretches 15 kilometers southeast of the village.

The road that leads from Nissan-Lez-Ensérune to the plateau today winds up its steepest flank in the east. It is probably, at least in its last section, on the original route of the access route to the oppidum. This is evidenced by the old silo terrace located a good 200 meters in front of the eastern entrance to the settlement north of this road, which was probably used for grain storage in silos and / or dolias until the settlement was left.

Hardly a kilometer further down the driveway crosses the ancient Roman road Via Domitia , which ran from northeast to southwest past the eastern flank of the hill and there for a short distance over a small pass.

In the south, terraces were created on the originally slightly more gently sloping slope, some of which are now fallow, but are also cultivated with vineyards and olive groves . To the west, the cypress -lined ridge merges with the plateau, which slopes gently towards the Poilhes hills.

From this height you can enjoy a wonderful view to the north of the Étang de Montady , which was a shallow lagoon of the Mediterranean until it was drained in the Middle Ages and was used for salt production, and to the south of the Canal du Midi and the vineyards.

This landscape, which has been shaped by human hands for centuries, has changed since the 6th century BC. Chr. Changed significantly. The plain, which was littered with lagoons connected to the sea by gullies, and criss-crossed by the deltas of the coastal rivers, offered the necessary protection for seafarers crossing the Mediterranean. As an outpost of the Cevennes , at the intersection of the great sea and land routes, Ensérune offered three important advantages: Despite the surrounding moorland, the place was dry, strategically protected due to its elevated position and was able to benefit from the brisk trade. However, there was a lack of drinking water as there was only one source, the Agoutis Spring, at the foot of the northern slope. They also helped themselves with numerous cisterns and other storage containers, some of which are still preserved today.

The area of the former pond, the Etang de Montady, which has been under landscape protection since 1974, extends over a 430 hectare natural depression. The perfect geometric structure, which is reminiscent of the spokes and hub of a huge wheel, is impressive. Ten radially arranged trenches, of which the three largest are called "Maires", flow into the "Redondel", a circular central trench in which all the water was collected and is still today, and then over the main trench, the "Grande Maire" drained into the approximately 400 meter long canal tunnel of “Le Malpas”. This underground aqueduct was the heart of the drainage system, crossing under the hill of Ensérune to its southern flank. From there the water flows through various channels, streams and Etangs into the sea.

In the 18th century, the origin of this structure was still unclear. It was dated both to the reign of Henry IV and to Roman antiquity. The truth was finally brought to light by General Andreossy (1804) and above all by Abbé Gineis, the "discoverer" of the village of Ensérune (1860):

On February 13, 1247, Guillaume de Broue, Abbot of Saint-Aprodise de Béziers and Archbishop of Narbonne, gave permission to a notary from Béziers and three landlords from Montady to drain the pond and pour the water into the pond of Capestang, of which he was the owner, derive. The construction of the structure took over 20 years. From the beginning, the owners and farmers of the parcels were responsible for maintenance. Today the 10-kilometer sewer network is managed by the Association of Landowners.

The Via Domitia was the first Roman road in Gaul and connected the Roman Empire with the Iberian Peninsula by the shortest land route. It was made between 120 and 115 BC. Built at the economic height and greatest extent of the oppidum, namely Ensérune III. It quickly developed into an important trade route, which was available for trade from and with Ensérune for 150 to 200 years before it was abandoned.

After 15 years of construction, the Canal du Midi has been connecting two oceans, the Mediterranean with the Atlantic Ocean, since it opened on May 17, 1681. It is 254 kilometers long and has 63 locks . The canal tunnel of Le Malpas, under the lower end of the eastern flank of the hill of Ensérune, 173 meters long, is a "technical marvel" of the time. It is the first navigable canal in a tunnel.

Between the medieval drainage canal and the 17th century royal canal, a railway tunnel was driven through the hill in 1854 that connects Sète with Bordeaux.

Discovery story

The ruins of the Oppidum d'Ensérune, hidden under sediments and thickets, were completely forgotten after leaving the village in the 1st century AD. Amazingly, the place was not mentioned in any Latin text. However, its ancient place name is not known. The names Anseduna and Amseduna appear in the 9th and 10th centuries and Ensérune and Anseüne appear in a 13th century poem. The Celts used the suffix -duna , which is present in the oldest forms, to designate an elevated position. Some researchers also refer to the prefix Anse , derived from an-t , which often stands for places in the Mediterranean area enthroned on steep heights. The term Puech d'Ensérune was mentioned in the 16th century, but it was to be replaced by Puéch de Saint-Loup by the Revolution , named after the patron saint of the small chapel built in the 5th century, the remains of which can be found on the Regismont winery are.

Abbé A. Gineis was the first to discover Ensérune, pastor of the village of Montady, on the northern edge of the entang of the same name. In Montady et ses environs (1860) he reported on walls, which he interpreted as fortifications, of silos and various other structural fragments that he had discovered between 1843 and 1860.

The large landowner and lawyer Félix Mouret, born in 1861, was an open-minded and inquisitive man. In 1915 he bought a piece of land at the western end of the hill and soon afterwards discovered the former necropolis with its cremation graves , where he and workers carried out excavations. However, he limited himself to the search for pleasing finds instead of being interested in the previous use of the site. In 1916 the Academy of Inscriptions and Fine Arts dedicated a protocol to his finds. By 1922 he uncovered 300 graves and in 1928 published the Corpus des vases antiques on the antique vases he found.

On August 11, 1922, Félix Mouret transferred his vineyard to the state, insisting that the entire property be listed as a historical monument. It was not until 1928, when the archaeologist Abbé Louis Sigal (1877–1945) was entrusted with the management of the official excavations, that the first scientific investigations of the site took place. The Latin and Greek teacher had assisted Felix Mouret for eight years. In 1934 the diocese reduced his workload, which allowed him to devote more time to his archaeological work.

Louis Sigal made Ensérune a place of research. The experienced scientist analyzed the different layers using the most modern stratigraphic methods, made precise surveys, longitudinal sections, plans, photos and notes. Although recording techniques are now out of date, Ensérune was declared an archaeological site of national importance in 1936 thanks to its extremely interesting reports. Since Abbé Sigal always wanted to deepen his investigations into infinity, unfortunately there was not a single publication.

Jules Formigé , an architect responsible for monument protection, was commissioned to build a museum at the excavation site in 1937. He decided to renovate and expand a villa built in 1914 by a jeweler from Béziers in the middle of a small park with cedar, cypress and pine trees at the highest point of the plateau. During the construction work, remains of ancient buildings were discovered in the basement of the house.

In 1945 Jean Jannoray took over the management of the Department of Cultural and Historical Antiquities. He was assisted by Abbé Josef Giry, the pastor of Nissan and Poilhes, who had an excellent knowledge of the site and who had been involved in the Sigal excavations since 1936. He was curator of the museum from 1941 to 1985 and died in 2001. Jean Jannoray, a former student of the Ecole française d'Athènes did not bring any noteworthy innovations with regard to the excavation methods, but he managed to create a comprehensive regional overview. In his 1955 published book Ensérune, contribution à l'ètude des civilizations préromaines de la Gaule méridionale , he inserted the oppidum into its historical context.

After his death in 1958 he was followed by Hubert Gallet de Santerre , professor at the University of Montpellier. He opened Ensérune for educational excavations, where numerous researchers were able to gain their first excavation experience. His study Les Silos de la Terrasse est , published in 1980, is still regarded as a standard work. Guy Barruol, who took over the department of cultural and historical antiquities from Languedoc-Roussillon in 1986, set new priorities. Above all, he wanted to save the endangered archaeological monuments of the entire region, which is why Ensérune, a now secured site, lost its priority role.

From 1980 onwards, the conservator Martine Schwaller and a team of experts uncovered graves in the necropolis that had been spared by Félix Mourer and his successor. In this way a reliable chronology and new hypotheses could be created. Renewed examinations enabled a more precise interpretation of the collections kept in the museum. In 1998, C. Dubosse added to the catalog of the Attic ceramics discovered here.

Restoration campaigns have been taking place in various parts of the village for several years. The previous soundings enabled a more precise historical assignment.

The Iron Age in Languedoc

Around 800 BC At the beginning of the Elder Iron Age , in southern France, especially in Languedoc, the prerequisites were given for the indigenous people to settle down in smaller market towns. Mostly they were hilltop settlements, but there were also some villages in the lowlands. In the oldest settlements, the local building techniques of the Younger Bronze Age continued to be used. For the dwellings, which usually consisted of one room, one still used predominantly rotable building materials, such as roofs made of branches or reeds, walls made of wickerwork that was stiffened with wood and pelted with clay. Sometimes stone foundations were used. The settlements separated vast pastures, their location was determined solely by the nature of the terrain. Hill settlements only slowly gained popularity in varying degrees. In the hinterland of the plains, the shepherds of the garrigue sought shelter in abrises and caves for a long time . In the flat coastal landscape, the establishment of lagoon settlements can be traced back to the local economic development, which was based there on fishing, collecting mussels and salt extraction (example: Lattes , Hérault). In any case, the indigenous peoples strove to expand their respective spheres of influence in order to ensure an adequate supply of food. During the control of the border zones between the hills and the plains, they encountered Phocean and Etruscan sailors who had been exploring the western Mediterranean region since the middle of the 8th century. The oldest Greek vases in this region, from the late 7th century, were found in the necropolis of Mailhac (Aude) and Agde (Hérault). Wine was drunk from these vessels: they were gifts from adventurous traders to the local population.

The first stone structures were built around 600 BC. Built about 20 years before the first settlement of Ensérune (around 575), on the banks of the Étang de Berre (Bouches-du-Rhone). This new construction method spread more or less quickly in most of the oppida in the coastal region of Languedoc. In the 6th century it can be found in Agde, Bessan (Hérault), Montlaurès (near Narbonne) and Pech-Maho (Sigean), and in the 5th century in Ensérune, Bédziers and Mailhac (Aude). In the younger Iron Age, which started here around 450 BC. In the beginning of the 3rd century BC, rectangular houses with only one room were preferred. The dwellings, made of natural stone and air-dried bricks, were now built along public facilities such as streets and fortification walls. In the 2nd century BC In larger and more elaborate houses, special functions were assigned to the various rooms.

The expansion of the urbanized areas during this period speaks for the independence and influence of the Oppida, who ruled and administered vast areas. However, nowhere, except in Marseille and in its colonies, do the remains of the settlements suggest a functional subdivision of urban space, such as administration, crafts, residential areas, religion. The oppidum of Languedoc and Provence differs significantly from the Roman or Greek city.

History of Ensérune

The settlement of the oppidum was divided into three large sections by Jean Jannorais, namely Ensérune I, II and III. However, this chronological framework, which was established a good half a century ago, no longer does justice to the latest findings.

Ensérune I

(Second quarter 6th to 5th centuries BC)

From the beginning of the Younger Iron Age (5th – 1st century BC) no remains could be found on the hill of Ensérune.

The first documented settlement consisted of rectangular, randomly arranged dwellings of simple construction. The rock was removed in order to create a floor of tamped earth on which the fireplace was located in a depression. The walls were made of wood-reinforced wickerwork on which straw clay was applied. The roof was made of branches that were sealed with clay.

The population, made up of farmers, shepherds, hunters and fishermen, stored their food supplies in silos carved into the bedrock, one of which was mostly built in the house. They used roughly shaped dishes, such as modeled ceramic pots. Their rather scanty tools consisted mainly of stone and a small amount of metal.

Ensérune II

(Late 5th to late 3rd century BC)

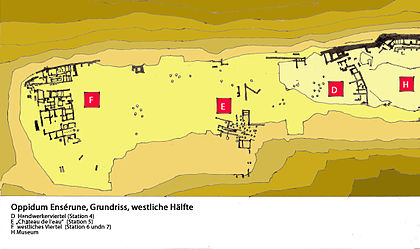

The structures that followed the dwellings of Ensérune I belonged to a properly structured settlement at the highest location, on the upper terraces on the southern flank of the hill, secured by massive retaining walls. (District G, Stations 8 and 10) The stone houses were built in areas delimited by streets. A checkerboard structure, which some believed they recognized, could not be confirmed. Their arrangement exclusively followed the topographical specifications.

The increased grain production led to a special development of the storage facility. The two silo fields on the west terrace (F, stations 6 and 7) and in the south-western quarter (E, station 5) suggest that grain and seeds, which are indispensable for the survival of a sedentary community, were collectively managed. The silos carved into the rock were gradually supplemented or even replaced by huge ceramic dolia, which also took place in the dwellings.

Ensérune II was hardly of military importance, but was especially of commercial importance. Mainly agricultural and handicraft products were traded on the market, such as weapons and Gallic jewelery made of metal, gray or with geometric ocher decoration, turned pottery from Catalonia and Languedoc, amphorae from Marseille and Greek vases. More than 500 individual cremation graves are known from the necropolis outside the fortification walls in the west. In the last quarter of the 5th century, the remains that were burned on a Ustrina were buried in a small pit with the fragments of the burned vessels. Not infrequently, a red-figure Attic bowl, which was also exposed to the flames, was deliberately smashed during the burial ceremony. Every now and then the grave was marked by a small stele with no inscriptions. 220 graves date from the second phase, which extended over three quarters of the 4th century. The bone remains were placed in an urn made of light clay, which was sometimes closed with a lid. The cremation was then scattered on the floor of the tomb. Every sixth grave contained small arms equipment, such as a sword and a lance, and ornaments.

In the 270 graves of the third phase (327-275 BC), the steles were replaced by stones. No more bowls were smashed, but an ash urn was placed in the middle of the grave, surrounded by food. Eggs, fish, poultry and perhaps milk and honey were placed in small bowls next to pieces of sheep and pork lying on the floor. The grave equipment was more or less valuable depending on age and social rank. The warriors' graves were particularly splendidly furnished. Their ashes were kept in huge craters introduced from Attica or Campania (southern Italy) and later from the Bay of Rosas (Catalonia) . The weapons that they took with them to the afterlife, with their special decorations, were characteristic of the Celtic world. Ossaries made of common or gray pottery have been found in other more modest tombs from the same period . This harmonious whole suggests a time of peace and prosperity.

Ensérune III

(Late 3rd century BC to late 1st century AD)

End of the 3rd century BC The oppidum d 'Ensérune was even better structured, although the buildings have still adapted to the topographical conditions, such as terraces.

In the 2nd century BC The city expanded to the southern flank and its former necropolis. (District G, stations 8 and 10) The reasons for this are still unclear, such as a population increase or the desire for larger houses and others. The streets were paved and canalized. The problem of drinking water supply was largely solved by building large, elongated cisterns that were lined and roofed with waterproof plaster.

In the 1st century BC A new quarter (District F, Stations 6 and 7) was built on the site of the former necropolis on the western flank, which was influenced by Roman and Greek traditions. The buildings were decorated with Doric and Ionic columns with capitals and bases , with wall paintings and floor mosaics . In the Italian style houses, numerous rooms were grouped around an open atrium with a colonnade. In the south of the quarter there was a large rectangular building, which was divided inside by five columns and is interpreted as a market hall. The growing prosperity of the people of Ensérune is particularly evident in the material improvement in their everyday life. The large number of tools and utensils that have been excavated is impressive. Many come from Italy, such as the ceramics from Terra Sigillata from Arezzo or those from southern Gaul. The different coin series indicate the beginning of the money economy. The indigenous coins with inscriptions in Greek or Iberian script prove the lasting influence of long-standing traditions and the resistance to the Latin language.

It was not until the 1st century AD, when the inhabitants left the oppidum to settle in the villas of the lowlands, which corresponded more to the economic system imposed by the Roman Empire, that the Roman influence became increasingly noticeable.

tour

Silo terrace

(A, outside of the actual tour)

The silo terrace is the first recognizable archaeological ensemble to the right of the ascending access road, just before the parking lot, near the entrance to the settlement area. (B, station 1)

This terrace was discovered by chance in 1966 when the road and the parking lot were being built. During the excavations carried out in 1966 and 1967, Hubert Gallet de Santerre and his students uncovered silos with depths of 1 - 3 meters in the yellow tuff . Most have the shape of a bottle with a narrowed neck, which is now usually reinforced with concrete, with a circular belly with a flat or rounded bottom. Some of the silos that were too close together had already collapsed, others were cut off at different heights at the top when the terrace was to be leveled and converted into arable land and later the road was to be built. A silo became visible in a longitudinal section in an embankment. As a result, important archaeological information was lost, which would have made it possible, for example, to determine whether the containers were created one after the other or at the same time, perhaps according to a certain plan or at longer time intervals in an arbitrary order.

Some served in the relatively distant past as dry storage sites for a wide variety of substances. The traces of fire visible on all sides on the inside of the silos on the coatings with fired clay suggest that the silos have undergone special treatments to prevent fermentation of the stored grain as food or seeds. In other places, due to various facilities such as clarifiers, channels and other drainage devices, it can be assumed that the silos were also used as cisterns. However, this hypothesis is controversial. Every now and then grave remains are found in silos, such as roughly hewn steles, or scattered bones that show no traces of crematation. Two silos, each containing a complete skeleton, were used as burial sites. The ceramics in it allowed a date between the 3rd century BC. BC and the 1st century AD Few fragments are remnants of earlier times.

Even if the introduction of collective storage of grain has not yet been precisely dated (4th century?), It can be assumed that it was carried out for a long time and only came to an end when the Oppidum d 'Ensérune was abandoned.

Silo and dolium in Ensérune

The silo is a 1 to 3 meter deep circular hole in the floor, the cross-section of which has the shape of a bulbous bottle, a bell or a cylinder, all with a narrowed neck that allows entry for maintenance purposes. The silos are chiselled into sufficiently stable subsoil, such as here in relatively easy-to-work rock made of tuff (volcanic ash). The walls were specially prepared to prevent fermentation of the stored substances. They were filled with clay, for example, which was then exposed to a fire in the silo or even just carbonized with fire. The stone-walled neck of the silo protrudes a short distance from the floor and was hermetically sealed with a stone or clay slab and clay. Grain could be stored in these silos from autumn to spring without fermenting. An unusually large number of such silos were established in Ensérune, the existence of which is documented from the 6th and 5th centuries, and which were used until the 1st century AD, either individually in a house or collectively on a special one Place amalgamated in large numbers, such as in the eastern silo terrace or the southwestern "Château de l'eau".

The Dolium (plural: Dolia) is a pot-bellied ceramic vessel made of terracotta, the thick walls of which are more or less fat-repellent. It was also spread in the Oppidum d'Ensérune from the late 3rd century BC. BC, where it displaced the silo in the new districts because the vessel dug or wedged into the ground ensured better food preservation. The containers, which were mainly used for storing grain, were also used to store oil and wine.

North flank

(District C, Station 2 and 3)

The approximately 15-meter-wide man-made terrace supported by a wall was only restored in 2006. The archaeologists, who uncovered its foundation walls between 1964 and 1967, interpreted it as the northern defensive wall of Ensérune II. A postern (exit gate of a defensive wall) is well preserved in this wall. The 1.6 meter wide opening crosses a sewage drain that comes from the street. A staircase in the west led to the spring that rises below. A residential area stretched over 250 meters along the street. The rectangular row houses each consist of only one room, the entrance thresholds of which have been preserved. Their walls are often interlocked and reinforced with large stone blocks. Almost all houses are equipped with a silo or dolium each, some longer houses with two or three storage containers. Some were built over an existing silo or dolium. In a residential building there is a newly assembled column in front of the back wall, on a square base, with a round shaft tapering upwards and a console-like capital, which obviously supported the ridge of the roof truss. In another house there is a cistern with two pillars of the former roof. At the western fork, the street was lined with other houses on both sides. The remains of other structures covered the slope up to the top of the hill, but fell victim to erosion, as they were obviously not covered with sediment, as with the preserved foundation walls. In their place is now a park-like garden.

The continuity of the settlement on the hill is particularly striking. Most of the dwellings came from Ensérune III, but were partly built on older foundations from Ensérune II. As a result of these repeated increases in the late 5th century, the terraces were created here. The oldest traces of settlement on the hill have also been discovered in this neighborhood, such as the wonderful stratigraphic sequence of the street, which dates back to the 6th century.

North flank, house with 2 Dolia

The controversial fortress of Ensérune

The stone fortifications are typical features of the hilltop settlements in the south of France. They go back to the 6th and 5th centuries, were repeatedly changed and supplemented, and were particularly widespread in the 4th century.

The first archaeologists assumed that this was a fortification built in the Ensérune II phase of development, which was then built at the beginning of the 2nd century BC. Was expanded to the west. After that, the defensive wall of Ensérune III, which extends over 2.5 kilometers, would have formed a geometric shape adapted to the terrain. The defense system would also have served as a retaining wall for the north terrace, which was built on with dwellings. To the west it would have been extended by a double vallum from a 15 to 18 meter wide and 3 meter deep trench. In the north and south of the highest elevation, a defensive wall equipped in places with a parapet was actually exposed. At least three posterns opened in it, but there are no signs of defensive towers . The irregular structure of the fortification of the oppidum was redesigned several times and also served as a retaining wall in various places. It is very likely that the defensive wall extended over the entire north ridge of the plateau. However, the existence of a defensive wall on the south side, which is populated with residential areas, could not be consistently proven. Even on the elevation west of the museum, no traces of a fortification have been found in current excavations at the location indicated by the first archaeologists. A wall uncovered in 1996 is certainly part of a land fortification. Whether the trenches were defensive trenches remains unproven for the time being, as they have not yet been subjected to any serious investigation.

According to this assumption, the two most important locations of collective storage facilities, the silo terrace and the “Château d'eau” would be outside the defensive ring. However, it is hardly conceivable that the surrounding storage facilities would have been left out when the houses were surrounded by walls.

For the time being, it is therefore assumed that the valley-side walls supporting the man-made terraces were built in the north and south of the hill in order to gain level building land. These walls, about 4.50 meters high, may also have had protective functions.

Drinking water supply

A main problem of the oppidum, the supply of sufficient drinking water, could not be fully resolved at first. The existence of only a single spring at the foot of the northern slope is indisputable, from which the residents got their drinking water and transported it up the hill. Perhaps they are already using simple techniques for collecting and storing rainwater. These techniques were better organized among the inhabitants of Ensérune II and III.

The use of silos or dolia as cisterns was by no means common. According to current studies, the use of such vessels as cisterns could only be proven in eight cases. In the entire oppidum, a total of ten public or private cisterns were dug into the rock or made of stone masonry, with a capacity between 18 and 77 cubic meters. Most of the rainwater was caught on the roofs of the houses and channeled into the cisterns. Only one cistern was found in one of the large houses with an atrium. There are also seven basins with a rectangular floor plan of very different sizes, from 0.75 to 2.60 cubic meters. They consist of masonry with mortar joints, which is lined on the inside with a waterproof plaster with brick dust. Their exact functions are still unclear as they are found next to cisterns in some houses. Presumably they were storage containers of other food than the one that was kept in silos or dolia.

- Gallery drinking water supply

The artisan quarter

(District D, Station 4)

The restoration work in 2001 and 2002 focused on the last phase of the oppidum, namely Ensérune III. A short plateau is followed by the plateau with the craftsmen's quarter. The pillars lying here, reused, come from a press. There was a fulling mill further south. A large elongated rectangular cistern was also uncovered there. Stamp impressions were found in it, the originals of which are presented in the museum. The magnificent masonry, in front of which there is an undeveloped section, is not part of a fortification system. Its actual purpose has not yet been clarified. From the studies carried out in 1998 it turned out that although it was undertaken in the Ensérune III period, it comes from an earlier phase. The exact execution of the masonry suggests a decorative function and is reminiscent of Iberian buildings.

- Artisan Quarter Gallery

"The Château de l'eau"

(District E, Station 5)

The "Château de L'eau" ("water tower") is located in front of a closed horizontal area with numerous silos and the remains of a large building. Of this structure, which has been redesigned several times, only two walls made of mortar-free masonry are left at right angles to one another. The purpose of this building, which was built on a terrace carved into the bedrock, is unclear; it has not yet been possible to date it. It was built from 1.00 to 2.25 meter long and 50 to 60 centimeter high stone blocks and was at least 22 meters long. The facade was 10 meters wide. So far it has not been possible to clarify whether the floor plan was simply rectangular or rectangular with a portico. It is also not known whether it was a Hellenistic building whose architectural style corresponded to the defensive wall of the oppidum of Saint-Blaise (Bouches-du-Rhone), or whether, as Jean Jannoray claimed, it was built in the 2nd century BC. BC.

To the south of it, a 50-meter-long section of a road was exposed that dates back to the 1st century BC. Was dated, but was probably older. The wheel tracks of the carts that were used here at the time can still be seen on the 3 and 5 meter wide lanes. The gutters of the houses that once lined the street flowed into the sewer, which was covered with stone slabs, as evidenced by the remains of mosaics and the fragments of the terra sigillata ceramics from La Graufesenque (Nahe Millaus, Aveyron) .

One of the houses had a 25-square-meter living room decorated with paint and mosaic paving. In order to ensure better conservation, it was covered with a protective roof. It probably served as a dining room or triclinium , which once housed three horseshoe-shaped dining sofas (triclinia). It is concluded that this area was inhabited until the oppidum left in the 1st century AD.

The incorrect name Château de l'eau (= water tower) owes the quarter to its deep storage tanks, which are known from the eastern silo terrace. Very early in the Enserune II phase, in the 4th century BC. BC (?) The inhabitants used the soft, water-impermeable tuff to embed about 40 silos in the ground. The area that was restored a few years ago was reinforced with a concrete slab. Some of the silos are five meters deep. Since several silos overlap one another, one can conclude that not all of them were created at the same time. Three silos are connected with each other with "tunnels", others have a common sewerage and drainage system more by chance (the often very thin walls were worn out and thus became leaky). Jean Jannoray, obsessed with the problem of water supply, interpreted this as evidence of the existence of an archaic cistern system. In reality, in almost all cases it was a device for dry storage of cereal grains. Its dating is also uncertain, as is that of the storage facilities on the west terrace. In any case, they are without a doubt a lot older than the uncovered remains of the living quarters there.

The west quarter

(District F, stations 6 and 7)

Originally the necropolis of Ensérune II was located there between the 5th and late 3rd century and consisted of over 500 cremation graves. However, only a few remains have survived in situ . The ruins restored in this quarter between 2001 and 2002 come almost exclusively from dwellings from the Ensérune III phase.

The necropolis stretched on the western end of the plateau, about 400 meters west of the buildings of that era. End of the 3rd century BC It was finally abandoned and had to give way to the residential area. It is still unknown where the Ensérune III cemetery was located. It may have shifted further down to the west, which is believed by recent accidental finds.

The necropolis of Ensérune II, with over 500 uncovered graves, is the most important burial ground from the younger Iron Age of Languedoc. In addition, the military equipment discovered here is distinguished by its special design and large quantity. The existence of Celtic artifacts from the 5th century on is undisputed. The increasing exchange with the Greek world in the 4th century is evidenced by the ceramics intended for wine consumption. The Iberian influence is also undeniable, because most of the black glazed ceramics of the 3rd century BC. From the workshops at the Golfe du Lion .

An east-west road, which was also found in other parts of the plateau, led to the residential houses and handicraft businesses that were built after the necropolis was abandoned. The wall visible in the north seems to come from a more recent era. It has been redesigned several times. Some of the houses were built before her. An exact overall plan of this quarter has not yet been drawn up.

The largest residential building stretched over 500 square meters and comprised about ten rooms, which were grouped around a central atrium based on the Roman model, which was undoubtedly adopted a few decades before our era. This house is considered to be the "oldest evidence of the Roman influence on the later Gallia Narbonensis ". It is said to have been in the second half of the 1st century BC. BC and used until the end of the same century.

A little further to the south is a rectangular 82 square meter room, which is bisected by a central colonnade. The pillars were probably made of wood, the stone walls rose on a foundation made of air-dried bricks and the presumed gable roof was covered with Tegulae with Imbrex . Whether this was a meeting place or a covered market could no longer be determined due to the poor condition of the remains, which were restored between 2001 and 2002.

The southern flank

(District G, stations 8 and 10)

To the south of the museum (H), a footbridge leads over a large rectangular cistern, the walls of which are provided with a waterproof coating. The entire quarter ascribed to the Ensérune III period is rather poorly preserved. A barely recognizable east-west street leads past rectangular, one-room houses with silos, one of which has collapsed. Murals were discovered in one. In the east of the district, a 70 meter long section was restored in 1988. The approximately 3 meter high retaining wall on the valley side is crossed by a sewer system made of flat bricks. It was once interpreted as a fortification and has been rebuilt. The residential buildings bordering on them line a street paved with small rubble stones in the north.

The western section of the district is more interesting. Here there is a large room with five dolia lined up in a row, a silo formerly used as a cistern and, above all, traces of a dwelling of Enserune I on the rock floor.

museum

(H)

The excavation findings are kept in the museum. The archaeologically extraordinary pieces can be viewed.

The presentation no longer corresponds to the current museographic standards (museum staging art) and is currently being reorganized.

The Sigal room on the ground floor is the same as between the 6th century BC. Dedicated to everyday life and trade that dominated the region from the 1st century AD to the 1st century AD.

On the first floor you enter the "realm of the dead". One of the finest collections of Attic vases in southern France is exhibited in typographical order in the Mouret Hall . In the Jannoray room, various complete grave furnishings can be viewed, including grave 163 of the Ensérune necropolis.

- Gallery museum

Black- and red-figure Attic vases from Ensérune

The numerous Attic vases from Ensérune come largely from the necropolis uncovered by Felix Mouret at the beginning of the 20th century and from the homes excavated by L. Sigal between 1929 and 1940.

The so-called black-figure technique, which was found in Athens around 600 BC. It spread quickly to Sicily, Etruria and Greater Greece and existed around 530 BC after the introduction of red-figure painting. Chr. Next to this new technique for some time and sometimes on the same ceramic. Then, however, the red-figure vases prevailed and were used until the end of the 4th century BC. It was exported in large quantities to the entire Mediterranean region, in particular to Languedoc and Catalonia.

It is not the firing process that distinguishes the two techniques, but the different surface treatments. In the first case, the black figures were painted on a red background, with the motifs being completed after the fire with cracks and white and red touch-ups. In the second case, the figures cut out in the black glaze were painted in red. The details were added with a brush instead of a stylus and the decorations made more elaborate. The motifs used were figures from mythology , such as the Amazons and Hoplite fights , Athena , Eros or Dionysus , from everyday life such as musicians, pugilists, dancers and others, and from the animal world (dog, cat, fish and others) or objects , like club, torch, cymbalum and others. The ceramics exist in numerous forms, such as kantharoi, bowls, craters , oinochoes or fish plates. The collection, organized by painting style or workshop ( Kalliope , London, Iena, Meidias Painter , and others) is an important source of documentation.

For numbers see illustration in the hand sketch.

The black glazed crater (1) is an ossuary that comes from a workshop in Rosas (Catalonia). The three large bowls with inwardly curved edges are of the same origin (only 2 and 3 are shown here), the bowl (5) is also glazed black. Among the grave goods that date back to the first quarter of the 3rd century BC An Attic fish platter (6), two handcrafted vases (7 and 8) and a balsamarium (10) also count . The weaponry was particularly well stocked, a sword with a central rib and a diamond-shaped tang, the scabbard decorated with lyre-shaped coral incrustations (11), a small spearhead with an ornate socket (12), a shield hump with rounded wings (13) and a narrow inner one Shield edge (14). In addition, a bronze belt chain with a decorated connecting link between ring and chain (15) and four remains of fibulae (16) were uncovered.

The relatively large amount of weapons from the 3rd century BC In 30 percent of the graves that were uncovered in the necropolis, it may be surprising in view of the rare weapons finds at other excavation sites.

Beginning and end of the 3rd century BC However, they are far more represented than the central phase of the same century, which is less true of the Oppidum d'Ensérune than of the rest of the Celtic world. This small difference is undoubtedly less due to increased military pressure than to the burial customs and social standing of the warriors in western Languedoc.

(Description Martine Schwaller, monument conservator)

Picture gallery

literature

- Jean Jannoray: Ensérune. Contribution to the étude des civilizations préromaines de la Gaule méridionale . Boccard, Paris 1955.

- Alix Sallé: Ensérune - a Gallic settlement. Édition du patrimoine Center des monuments nationaux, Paris 2007, ISBN 978-2-85822-963-5 .

- Rolf Legler: Languedoc - Roussillon: From the Rhone to the Pyrenees. DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-7701-1151-6 , pp. 16-17 and 318.

Web links

- Official site (French)

- French text and images

- photos

- Ministry of Culture (old photos and sketches of the excavations)

- French text

- A very good Panorama of the Oppidum

- Etang de Montady

Individual evidence

- ^ Alix Sallé: Ensérune - a Gallic settlement. Édition du patrimoine Center des monuments nationaux, Paris 2007, ISBN 978-2-85822-963-5 , pp. 1–55.

- ^ Alix Sallé: Ensérune - a Gallic settlement. 2007, pp. 4-7.

- ^ Alix Sallé: Ensérune - a Gallic settlement. 2007, pp. 8-12.

- ^ Alix Sallé: Ensérune - a Gallic settlement. 2007, pp. 14-21.

- ^ Alix Sallé: Ensérune - a Gallic settlement. 2007, pp. 25-31.

- ^ Alix Sallé: Ensérune - a Gallic settlement. 2007, pp. 33-51.

- ^ Alix Sallé: Ensérune - a Gallic settlement. 2007, pp. 34-35.

- ^ Alix Sallé: Ensérune - a Gallic settlement. 2007, pp. 46-47.

Coordinates: 43 ° 18 ′ 37 ″ N , 3 ° 6 ′ 49 ″ E