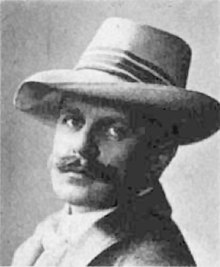

Paul Lensch

Paul Lensch (born March 31, 1873 in Potsdam , † November 18, 1926 in Berlin ) was a German journalist , university professor and politician ( SPD ). From 1912 Lensch was a member of the German Reichstag for the SPD, from 1919 he was professor of economics at the Berlin University .

Life

Lensch studied Hegel and Marx as a high school student . After completing his military service with the 4th Prussian Guards Regiment on foot , he studied political economy in Berlin and Strasbourg. During his studies he became a member of the Neogermania Berlin fraternity (1895) and the Arminia Strasbourg fraternity (1897). In 1900 he was in Strasbourg to the doctor of political science doctorate . He then worked as editor of the Free Press for Alsace-Lorraine . From 1902 he was editor of the Leipziger Volkszeitung and alongside Rosa Luxemburg , Alexander Parvus , Franz Mehring and Karl Liebknecht spokesman for the anti-revisionist left in the SPD, especially at the party conventions in Essen (1907), Jena (1911) and Chemnitz (1912). From 1907 to 1913 he was editor-in-chief of the Leipziger Volkszeitung . In 1912 he was elected to the Reichstag as a candidate of the SPD for the 22nd Saxon constituency of Reichenbach . There in August 1914 he was initially one of the opponents of the approval of the war loans within the SPD parliamentary group . From 1915 the Lensch-Cunow-Haenisch group was formed within the SPD and tried to justify the position of the party majority on the issue of war credits in a Marxist way. They developed the theory of " war socialism " and published it in the Hamburger Echo and other SPD party papers. From mid-1915, Die Glocke , a magazine founded by Alexander Parvus, became the organ of the group. In October 1917 the SPD split up. Lensch became one of the journalistic spokesmen for the majority SPD around Friedrich Ebert .

In November 1918 Lensch became an important contact between the Council of People's Representatives and the military leadership. Then he withdrew from party politics. In 1919 he received an extraordinary professorship for history at the Berlin University. The appointment was enforced against the will of the Philosophical Faculty Berlin by his friend Konrad Haenisch , who had been appointed Prussian Minister of Education after the revolution. In addition, Lensch became a foreign policy employee of the Berliner Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung , which from 1920 belonged to Hugo Stinnes , the industrialist from Mülheim and a member of the DVP Reichstag. In 1922 Lensch resigned from the SPD and anticipated an expulsion from the SPD, which had moved to the left after the merger with the rest of the USPD and the return of Marxist theorists such as Karl Kautsky and Eduard Bernstein . From June 1922 to November 1925 Lensch was editor-in-chief of the DAZ and increasingly became an opponent of social democracy close to the right-wing conservative camp. At that time, the DAZ's publishing director was the former German naval attaché in Constantinople, Hans Humann .

Lensch died on November 18, 1926 after a serious illness in Berlin. His grave is on the south-west cemetery in Stahnsdorf .

Political ideas

War socialism

For Lensch, the war proves the failure of capitalism. Since capitalism, which is based on competition and free markets, resorts to socialist economic regulation measures, the superiority and victory of the socialist principle for Lensch is proven. The state uses a grain monopoly to ensure the food of the population, bread cards are introduced. For Lensch this is an indication of a change in the economic principle towards a “democratic war socialism”; the lack of basic needs during the war is basically a godsend for him, as it enables state planning to take place. The revolutionary character of the war can be seen here. He later continues this in his interpretation of the world war. According to Lensch, the state is an institution that stands above the classes. The state does not regulate class-specifically, but according to objective interests. This is the success of the war and thus the interests of the whole people. According to Lensch, this socialism should not be achieved through class struggle, but through national reconciliation. The cultural identity and the economy should be linked - important for the thesis “World War as World Revolution”. Lensch's theses depart from the typical Marxist view. Large national industry, a bureaucratically regulating state and a strong workforce represent the new socialist “ national community ” for Lensch . Socialism is not to be seen in this society. The examples shown by Lensch would only make society ripe for socialism.

World war as a world revolution

The First World War is interpreted by Lensch as a world socialist revolution. It is the continuation of the theory of war socialism. While most of the SPD saw the war as a defensive war against tsarist Russia, Lensch believed that liberal England was the cause of the war. England was the earliest industrialized country in Europe. This is how it achieved its supremacy. The war against Germany is now only an attempt to prevent the opposing Germany from growing and to secure its own monopoly.

Lensch converts the Marxist theory of the world revolution to a national level. England is the bourgeois capitalist class and Germany is the proletariat .

For Lensch, England and its parliamentary monarchy are the origins of capitalism. The Calvinist religion and the pursuit of individual prosperity led to the establishment of the bourgeoisie in England. This English company has an expansive pursuit of markets outside the UK and is therefore establishing a monopoly. Germany, which is now emerging, is now endangering this supremacy because, in contrast to individualistic England, it is a country that is strongly characterized by solidarity and has no conventional bourgeoisie . He explains this with the Thirty Years War and a lack of unification in Germany until the 19th century.

Germany was not as reactionary as was assumed in the world during the times of the Wilhelmine Empire , democratic elements had developed and these would gain in importance. In Germany - and not in liberal England - universal suffrage was introduced, for example the general compulsory schooling , which creates a national “cultural community”, is superior to the English. Lensch also mentions general conscription , which is basically socialist in contrast to the British militia army.

Lensch does not deny the shortcomings in Germany, but emphasizes the strength of the German proletariat compared to that of the foreign. German unions are the strongest and most closed. The British labor movement, however, was not interested in the destruction of the English monopoly because of the privileges which the bourgeoisie granted them. The workers' leaders and workers want to keep these privileges and therefore support the government in the war. Inferring from this, the victory of Germany would be a victory for international socialism. A victory for England, on the other hand, would set Germany back for years and mean the end of socialism.

The ideas of socialism that Lensch envisions are not the typical Marxist ones. Rather, it is about creating a national solidarity, which is characterized by state and moral obligations. Lensch is not alone with this positive interpretation of Germany's historical “Sonderweg” in contrast to the liberal model country England. Numerous authors at the time emphasized the superiority of German “culture” over superficial, individualistic-capitalist western “civilization” and the ideas of 1914 against Ideas from 1789 . Because Lensch mixes this with Marxist ideas to form an authoritarian, nationalist model of socialism, there is a similarity in his thinking and the like. a. on national Bolshevism around Ernst Niekisch .

Criticism from his contemporaries

Lensch's theories cannot be classified into the usual left and right categories within the SPD. While the left completely rejects the war as a war of aggression in Germany, reactionary Russia is the great opponent for the right wing of the SPD. Lensch and his group form a new direction in the SPD.

To war socialism

The unions make similar arguments in support of the war as Lensch, e. B. Solidarity of workers. The majority of the SPD points out that capitalism only builds monopolies in order to secure its continued existence during the war. The measures are only due to the war. This is discussed in detail in Vorwärts , the SPD organ. The introduction of a monopoly in the grain sector would not bring about any real change. Mill owners and bakers would continue to have the same profit. Eduard Bernstein wrote several critical articles.

With his theories on war socialism, Lensch met with criticism on both the right and the left. At the same time, Lensch also found space for his theses in Vorwärts . His theses on the causes of the world war were only criticized from the left. In the rest of the SPD, Lensch found more and more acceptance over time.

research

There are two main branches

- Robert Sigel: The Lensch-Cunow-Haenisch Group. 1976:

Here Lensch is interpreted within the SPD. A classification in the newly emerging revolutionary right is not made. Only the right wing of the SPD is analyzed. Lensch is also seen here as a new form of the SPD's right wing, which differs from the revisionists and conservatives. The new form of the völkisch-socialist society is addressed in Lensch's theories.

- Rolf-Peter Sieferle: The Conservative Revolution :

Many aspects like in “The Lensch-Cunow-Haenisch Group” are dealt with here. However, Lensch is viewed from a different angle. He is included in the development of a new right. Lensch's national orientation is highlighted more clearly. The ethnic aspect leads to this classification. National socialism is clearly distinguished from the previous one and therefore placed in the ranks of the conservative revolution. Lensch is not alone with this positive interpretation of Germany's historical “Sonderweg” in contrast to the liberal model country England. At that time numerous authors emphasized the superiority of German “culture” over superficial, individualistic-capitalist Western “civilization” and the ideas of 1914 against Ideas from 1789 . Because Lensch mixes this with Marxist ideas to form an authoritarian, nationalist model of socialism, there is a similarity in his thinking and the like. a. on national Bolshevism around Ernst Niekisch .

literature

- Robert Sigel: The Lensch-Cunow-Haenisch Group. A study on the right wing of the SPD in the First World War. (= Contributions to a historical structural analysis of Bavaria in the industrial age, Volume 14). Duncker and Humblot, Berlin 1976, ISBN 3-428-03648-4 .

- Gisela M. Krause: Lensch, Paul. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 14, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-428-00195-8 , pp. 215-217 ( digitized version ).

- Rolf Peter Sieferle : The birth of national socialism in the world war. Paul Lensch. In: Rolf Peter Sieferle: The Conservative Revolution. Five biographical sketches. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-596-12817-X .

- Helge Dvorak: Biographical Lexicon of the German Burschenschaft. Volume I: Politicians. Volume 3: I-L. Winter, Heidelberg 1999, ISBN 3-8253-0865-0 , p. 271.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Helmut Kraussmüller and Ernst Anger: The history of the General German Burschenbund (ADB) 1883-1933 and the fate of the former ADB fraternities. Giessen 1989 (Historia Academica, issue 28), p. 103.

- ↑ Michael Grüttner among others: The Berlin University between the world wars 1918-1945. Berlin 2012 (= History of the University of Unter den Linden , Vol. 2), p. 126.

Web links

- Literature by and about Paul Lensch in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Paul Lensch in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Paul Lensch in the database of members of the Reichstag

- Paul Lensch's biography . In: Heinrich Best : database of the members of the Reichstag of the Empire 1867/71 to 1918 (Biorab - Kaiserreich)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lensch, Paul |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German journalist, university professor and politician (SPD), MdR |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 31, 1873 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Potsdam |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 18, 1926 |

| Place of death | Berlin |