Progress (student movement)

The Progress was a liberal reform movement in the German student body between 1840 and around 1855. It also included those professors who were not full professors.

meaning

Following on from the ideals of the original fraternity , the student body campaigned for the abolition of special academic rights vis-à-vis the citizenry, the abolition of academic jurisdiction and the equality of all students. In its radical variant, the Progress temporarily strived for the complete abolition of the traditional student associations in favor of general student representatives , but could not gain acceptance.

As a result, the challenge posed by the Progress led to reforms within the existing connections and thus ultimately to the consolidation and further differentiation of the connection system: on the one hand, new forms of corporation emerged, including reform country teams and gymnastics associations , and on the other, supraregional associations such as B. the Kösener SC Association .

root

The intellectual historical foundations of the Progress lie in the French July Revolution of 1830 . After the unity movement stagnated in Germany at the beginning of March , it experienced a new upswing from 1830. Events like the Hambach Festival in 1832 articulated the bourgeois camp's need for unity and freedom. However, with the failure of the Frankfurt Wachensturm in April 1833, the movement suffered a significant setback.

course

The student progress resembled the Urburschenschaft ; However, Germanness did not play such a major role. The progress remained moderate until about 1845, after which it radicalized and demanded the abolition of the previous student forms. He called for the abolition of the special student position vis-à-vis the bourgeoisie , the abolition of academic jurisdiction , the equality of all students and the abolition or restriction of dueling . The radical progress was to be found in the fraternities , the country teams and, occasionally, in the corps ; the corps were rather hostile to the progress because they claimed leadership of the student body. Gustav Struve was a protagonist of the Progress .

The effects of the progress on the connections were different. There were occasional splits of ties as the fronts between the supporters of the moderate progress and the radicals had hardened. In Jena , the question of whether non-academics could become members led to a split in the fraternity.

Professorships

In the university faculties , the March Revolution expressed itself primarily as a struggle for expanded rights for non-ordinaries. Their resentment was directed against the exclusive leadership of the universities, the "caste spirit" and the (organizational and financial) privileges of the ordinaries . They demanded equal rights for all university teachers .

From September 21 to 24, 1848, 123 university lecturers from 18 German universities gathered in Jena . Of the Austrians, the University of Vienna alone (with nine delegates) was represented. This reform congress described itself as a purely advisory and appraising body and wanted to maintain and develop the idea of the university. By involving the Senate , he moderated the demands of the radicals. In his opening address, Ernst Christian Gottlieb Jens Reinhold , Vice Rector of the University of Jena , wished all the “German science centers” to work together in the sense of “our newly awakened unified popular life, our German national consciousness”. At issue were the liberties and autonomy of universities, freedom of study, the use of the Latin , the omnipotence of the Senate and academic jurisdiction .

A second meeting was scheduled for the fall of 1849; but it did not materialize because of the Baden Revolution . The attempt by the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg to bring the conference together for September 1850 also failed . The Progress was less successful with the professors than with the students. The legal and material strengthening of the non-ordinaries had to be fought for in later years.

"Black Progress"

In the 1860s and 1870s a new progressist wave emanated from the reform country teams , which, however, did not gain much influence and shook student life nowhere near as much as the first Progress. It created academic choral societies or philosophical, mathematical and other societies and led to the founding of the "black" (non- colored ) associations. Through the ongoing struggle for their equality, they contributed significantly to the recognition of all corporation associations ; However, it was only realized after the First World War in the Erlangen Association and Honorary Agreement .

The "black progress" took on many unfulfilled demands of the first progress, for example the abolition of academic jurisdiction , legal regulation of academic disciplinary power, establishment of student committees, reading rooms and improvement of social facilities, especially for poor and sick students. New chairs , the strengthening of private lecturers and a more rational division of the study regulations were also called for .

The long-term goal was the abolition of color and the greatest possible restriction of the duel and the scale .

See also

- Burschenschaft Hannovera Göttingen # Prehistory, foundation and early days

- Hochhemia at the Albertus University

- Reform country team

- Free student body

literature

- Peter Brandt: From the original fraternity to progress. In: Harm-Hinrich Brandt , Matthias Stickler (eds.): "Der Burschen Herrlichkeit". History and present of student corporations (= publications of the Würzburg City Archives. Vol. 8). Schöningh, Würzburg 1998, ISBN 3-87717-781-6 , pp. 35-53.

- History of the German fraternity. Volume 3: Georg Heer : The time of progress. From 1833–1859 (= sources and representations on the history of the fraternity and the German unity movement. Vol. 11). C. Winter, Heidelberg 1929.

- Karl Griewank : German Students and Universities in the Revolution of 1848 . Weimar 1949

- Thomas Hippler: The "Progress" at the Berlin University 1842-1844. In: Yearbook for University History . Vol. 7, 2004, ISSN 1435-1358 , pp. 169-189, ( digital version (PDF; 171 kB) ).

- Konrad Jarausch : German students. 1800–1970 (= Edition Suhrkamp. 1258 = NF Bd. 258 New Historical Library ). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-518-11258-9 , pp. 47-57.

- Harald Lönnecker , Peter Kaupp : The Burgkeller or progress library of the Arminia fraternity on the Burgkeller-Jena in the Koblenz Federal Archives , Bestd. DB 9: German Burschenschaft, Society for Burschenschaftliche Geschichtsforschung e. V. Archive and Library, Frankfurt am Main 2002.

- Friedhelm Golücke : Progreß , in: Student Dictionary . Student und Hochschule from A to Z, 5th, completely revised and expanded edition in four volumes, published on behalf of the Association for German Student History and the Institute for German Student History . Essen 2018, ISBN 978-3-939413-68-4 , Vol. 1, Part III of IV, pp. 375–377.

Web links

- Corps and Progress ( Memento from June 11, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- The "Burgkeller" or "Progress Library" of the Arminia fraternity on the Burgkeller-Jena (Federal Archives, 2002)

Remarks

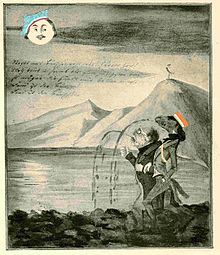

- ↑ Probably the only picture of the progress with the Masurian moon and spitting Palmburgers is a reference to the moon by Johann Gottfried Herder : “And grieves you, noble, one more word / The little envious fellow? / The high moon, it shines there / And makes the dogs bark / And remains silent and quietly walks away / Brightening up what is night. ”In 2001 the picture was colored.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Robert Paschke : Student History Lexicon. GDS archive for university and student history. SH-Verlag, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-89498-072-9 .