Quaternions of the Imperial Constitution

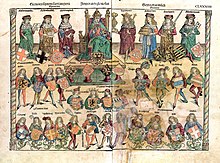

The quaternions of the imperial constitution have been a system of order that has been documented since the early 15th century, with which the aim was to illustrate the corporate hierarchy in the Holy Roman Empire . The individual groups are arranged in groups of four of the same rank, so-called Quatuorviraten.

description

If one ignores the depiction of emperors and electors , which cannot be found in all depictions, then there are ten quatuorvirates, from the dukes of the empire to margraves , landgraves , burgraves , counts , knights , nobles , cities , villages , up to the peasants, depicting the secular classes of the empire. The representation in ten groups of four can be traced back to a number symbolism , which is supposed to represent the kingdom as a natural or divine creation.

Time of origin

The exact origin of the quaternions can only be proven on the basis of indications. The oldest, more secure, dated evidence for the quaternions is the “Proverb ... warped the Roman Empire in the beginning and how to come from” ( Proverb from the Roman Empire ) from 1422 (especially verses 103-140). However, the system would have to have been developed before the elevation of Savoy to a duchy, as this territory can still be found under the counts. They probably originated a little earlier under King Sigismund . In 1414, he arranged for the emperor's hall in Frankfurt's Römer to be painted , showing the emperor in a large format with figures that were about half the size and bearing coats of arms in the form of quaternions. The fact that the initiative for this design can actually be traced back to Sigismund can be seen, among other things, from the fact that Frankfurt cannot be found in the representation. The electoral city of the Roman-German rulers would certainly have had no interest in putting a scheme in its town hall that ignored its own importance in the empire. Following this attitude, the Frankfurters demonstratively attached a large-format Frankfurt coat of arms under the image .

Origin and reference to reality

A closer look at the quaternions reveals that the way they are depicted does not “harmonize with the real state constitution” ( Johann Jacob Moser ), ie has no relation to the actual imperial constitution . The allocation of some classes is puzzling and illogical from the point of view of the imperial constitution: The imperial cities appear in the Quatuorviraten as "farmers" and "villages". Cologne can be found next to Constance , Regensburg and Salzburg with the four farmers of the empire. The Cologne farmer as a symbolic figure of the Cologne Carnival goes back to this assignment. Under the burgraves of Stromburg, Strauburg or Strandeck (the name varies in the representations), not even contemporaries were able to identify exactly who is behind them or whether these burgraves really exist.

In addition, the representation is a limited selection of the actual existing and important estates of the empire. Spiritual rulers are not included in the system of order. Nor are Habsburg territories and Württemberg to be found in the quaternions, but the long-lost Duchy of Swabia is represented among the dukes .

This system is therefore not a random selection of the individual stands, but a well-developed, relatively fixed system that can probably be traced back to an original from Sigismund. The selection of the stands shown shows above all the network of relationships of his father Charles IV. Sigismund is likely to have taken over large parts of this network. Its political opposition to Habsburg and Württemberg also explains the absence of these actually important and powerful imperial estates. It is more difficult to understand the choice of the lower and politically insignificant classes, some are ultimately simply chosen arbitrarily, as in the case of the landgravates , since there is only a small number of them in the empire that is just enough to do justice to the scheme.

Deviations in the presentation are seldom due to the template and can be traced back to uncertainties and errors in the distribution of the presentation. For example, depending on the representation, Mainz (actually not an imperial city at all) or Metz can be found among the cities , as well as Upper Alsace and Lower Alsace alternate with the Landgraves.

distribution

By the 16th century , the quaternions were incredibly widespread in the empire. In addition to the coats of arms figures, other ways of representation were created. They were reproduced in proverbs or texts. After the double-headed eagle was established as a symbol of the empire (it was introduced in Sigismund's seal in 1433), the representation of the quaternions on the individual wings of an imperial eagle ( quaternion eagle ) was particularly popular, in which the eagle itself symbolizes the empire as a whole, in its body or Plumage to blend in with the stands. This can be found on the widespread imperial eagle tankard since the second half of the 16th century . The representation spread above all in single-sheet prints and heraldic books, e.g. in illustrations of the heraldic books of Conrad Grünenberg , Konstanz , provided with colored pen drawings or opaque colors (original, paper manuscript 1483 in the secret state archive in Berlin and, quickly created on parchment, in the Bavarian State Library in Munich) . It also appears in various card games of the time. The quaternion scheme was also used to decorate city council rooms. The Frankfurt depiction has long since ceased to exist. The most important surviving pictorial depiction of the quaternions is the Ueberlingen town hall, created by Jakob Russ from the last decade of the 15th century . It is precisely the stands named in the scheme and, above all, the cities that contribute to the spread. The increasing popularization leads to an increased dissolution of the originally fixed system organized according to number symbolism. The original scheme was no longer understood in the form originally intended. The expansions gave free rein to creativity. Four hunter masters of the empire can be found as well as imperial banners, castles, abbots, monasteries and imperial hamlets. In the late 16th century the system finally turned into a heraldic gimmick.

meaning

When it was first created, the quaternion scheme was anything but a "learned" gimmick, but a first concrete visualization of the empire and for the common man with all hierarchical levels: "This is the order of the rich, it includes farmers and citizens, noble and ignoble."

The fact that only secular gentlemen can be seen could be related to the Council of Constance . Accordingly, the Quatuorvirate visualize the protectors of the church and the Christian population of the empire. Not only the emperor or the elector, but from the duke to the peasant everyone is tasked with ensuring that the council is called and held. In this respect, the scheme should be understood as a list of church protectors in the empire.

The concentration on a national German component, which at the end of the century is also reflected in the name of the Holy Roman Empire with the addition of "German Nation", is already evident in the quaternions, because all quaternions come from the "narrower German area" (Savoy was already added to the German part of the empire by the former Burgundian part of the empire.)

The frequent lack of electors in the scheme was a heraldic expression of the tense relationship between Sigismund and the Rhenish electors, and the role of the other estates is confirmed by the explicit lack of electors as the most important and powerful members of the empire. The dualism between emperor and empire remains in the scheme, but here there is no expression of royal rule and royal legitimacy, but a rule of or on the basis and consent of forty estates.

In this list, a new form of the imperial idea is also concretized . As a new symbol, they displace the previously typical representation of the empire as a community of the electors with the emperor. The electoral princes alone no longer form the empire or are pillars of the empire, but the totality of the estates. The quaternions metaphorically reflect the changes in the political structure of the empire that took place up to the end of the 15th century, and they may even make their own contribution to the reform of the empire .

Political relevance

The quaternions are a constructed and unrealistic construct from the imperial constitution, but in the perception of contemporaries they were taken very seriously and in some cases also considered to be the original, unspoiled and true order of the Holy Roman Empire. It was not infrequently printed together with the Golden Bull and is also part of Schedel's world chronicle . In 1480 Albrecht Achilles von Brandenburg thinks, for example, “that we know and know is authentically documented that around vil hundred years ago the hailig Rhomisch Reych was originally set up, among other things, on sixteen principals, namely four hertogthumb, four marggrafschaff, four landtgraffschaff and four Burggrafthumb . " the Wittelsbach Ludwig the rich points out that Bavaria was " the four heuser ains, to the holy Roman Empire is dedicated " .

It was not only an honor to belong to the scheme, even political claims were justified with the quaternion scheme and this was perceived as part of the applicable law. At the Reichstag in 1507, the Duke of Braunschweig justified his claim to a higher-ranking seat in the event of a session dispute with his position in the quaternion order. In 1653/54 and 1708/10, the Bishop of Münster justified his right to vote in the Count's Bank on several occasions, referring to the alleged vote of the Burgraves of Stromberg. For smaller estates, membership of the scheme was a guarantee of imperial immediacy and protection from the efforts of more powerful neighboring princes to mediate. Charles V has the Counts of Rieneck their imperial immediacy in 1526 confirmed due to their mention in Quaternionenschema.

Only with the change to a more mechanistic, enlightening conception of the state in the 18th century, the curious doctrine came to an end and was increasingly regarded as "a ridiculous and useless invention of idle minds." ( Johann Jacob Moser ) Nevertheless, they continued to be one in the 18th century didactic value ascribed: "Although the quaternions in the Teutsche Reich are without reason, they serve to enable one to learn the names of some distinguished Teutscher houses from them." (Tobias Lotter, 1762)

Proverb from the Roman Empire 1422 (excerpt in the facsimile of the edition)

literature

- Ernst Henrici: Saying from the Roman Empire from 1422 . In: Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum 25 (1881), pp. 71-77 ( PDF digitized from Gallica )

- Albert Werminghoff : The quaternions of the German imperial constitution . In: Archive for Cultural History, Volume 3 (1905), pp. 288–300 - digital version ( PDF )

- Hans Legband: On the quaternions of the imperial constitution . Miszelle in: Archive for Cultural History, Volume 3 (1905), pp. 495–498 - digitized version (PDF)

- Ernst Schubert : The Quaternions . In: Journal for historical research 20 (1993), pp. 1-63

- Bernd Konrad: Illumination in Konstanz, on the western and northern Lake Constance from 1400 to the end of the 16th century . In: Eva Moser (Ed.): Illumination in the Lake Constance area. 13th to 16th centuries . Gessler, Friedrichshafen 1997, ISBN 3-86136-002-0 , pp. 311/312, KO 72, KO 73; P. 119 on Grünenberg's book of arms (full-page color illus. From fol. 89r: Four castles of the Holy Roman Empire ).