Edmund Fitzgerald (ship)

|

The Edmund Fitzgerald in the St. Marys River, May 1975

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

The Edmund Fitzgerald was an American cargo ship that sank on November 10, 1975 during a storm on Lake Superior . All 29 crew members were killed. The accident is the most famous catastrophe in the history of shipping on the Great Lakes . The misfortune achieved worldwide fame through the Canadian folk singer Gordon Lightfoot , who processed the events of the downfall in his ballad The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald .

The ship

On February 1, 1957, the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company of Milwaukee hired the shipbuilding company Great Lakes Engineering Works to build a Great Lakes ship , a bulk carrier for the transport of iron ore . The contract contained the clause that the ship should be the largest on the Great Lakes. The keel was laid on August 7 of the same year, and before the ship was christened and launched on June 8, 1958, the Northwestern decided to name the ship after her newly elected General Manager Edmund Fitzgerald, whose father had already been a captain on the Great Lakes.

The completed ship was with a length of 222.20 m, as contractually agreed, the largest ship on the Great Lakes; this record lasted until 1971, after which larger freighters appeared. The Edmund Fitzgerald was divided up as a conventional Great Lakes ship, it had a deckhouse in the front , an aft engine system and three holds in the middle of the ship with a bulk volume of 24,384 m 3 . The cargo was handled through 21 hatches each measuring 3.53 × 16.5 m, the hatch covers of which were made of 8 mm thick steel. The loading capacity was 24,131 tons .

The drive consisted of two Westinghouse steam turbines, the combined power of which was transferred to the propeller shaft via two reduction gear stages. The ship's steam boilers were originally coal-fired, but were converted to oil firing during the winter break of 1971/1972.

More than 15,000 people were present when the ship was launched. Even this ceremony was not without its difficulties. When Mrs. Fitzgerald wanted to christen the ship with a champagne bottle, it took three attempts before the bottle burst. The launch was delayed by 36 minutes because the shipyard workers had difficulties releasing the keel block supports. When the ship then slid sideways into the water, it hit a dock with full force.

Sea trials began on September 13, 1958, and the Northwestern Company turned the ship over to Oglebay Norton Corporation a week later . For the next 17 years, the Fitzgerald transported taconite from mines near Duluth to steel mills in Detroit , Toledo and other ports. Before the events of November 9, 1975, she was involved in five collisions, ran aground in 1969, collided with the Hochelaga in 1970 and later in the same year hit a lock wall , which happened twice in the following years. In 1974 she also lost her original bow anchor in the Detroit River .

The downfall

The Edmund Fitzgerald left Superior Harbor on the afternoon of November 9, 1975 under the command of Captain Ernest M. McSorley. She was on her way to a steel mill near Detroit , laden with taconite . Almost at the same time a second freighter, the Arthur M. Anderson , coming from Two Harbors to Gary was en route and joined her. The captains of the two ships agreed to sail the route together, not least because of the bad weather. The Fitzgerald took the lead as the faster ship, while the Anderson followed with a few miles behind.

The two ships, which sailed Lake Superior at 13 knots , soon got into a severe winter storm with wind speeds of over 50 knots and waves up to ten meters high. Due to the storm, the Soo locks in Sault Ste. Marie closed. The freighters changed course northwards to be sheltered from the wind along the Canadian coast. They later swiveled towards Whitefish Bay to reach the locks.

In the late afternoon of November 10, sustained winds of 50 knots were still observed in the east of Lake Superior. The Edmund Fitzgerald was hit by a hurricane-force gust of 75 knots. At 3:30 p.m. the crew radioed the Anderson and reported a slight list as well as damage to the deck including loss of the radar. Visibility was poor due to the heavy snowfall and the US Coast Guard had issued a warning that all ships should enter a safe harbor. The two bilge pumps of the Edmund Fitzgerald ran in continuous operation to pump around the penetrated water. The lighthouse and radio beacons at Whitefish Point had been disabled by the storm, so the Edmund Fitzgerald , who was still ahead of the Anderson , was practically blind at the time. So she slowed down in order to get within range of the Anderson's radar and receive radar support from them.

For a while the Anderson piloted the Fitzgerald towards the relative safety of Whitefish Bay. At 5:45 p.m., Captain McSorley radioed another ship (the Avafors ) and reported that his ship was listing heavily , had lost both radars and the waves were continuously lashing over the deck. McSorley described the situation: "One of the heaviest lakes I have ever seen". The last radio message from the wrecked ship was received at around 7:10 p.m. when the Anderson reported to the Fitzgerald that she had been hit by a giant wave that was now moving in the direction of the Fitzgerald . When asked about the situation, McSorley replied: "We are holding our own." (for example: "We can do it", "We can get through it"). Only a few minutes later the ship must have sunk, no distress signal was received. Ten minutes later, the Anderson could neither radio nor see the Fitzgerald on the radar . At 8:32 p.m. Anderson informed the Coast Guard of their concern about the ship.

The search

Immediately after the Anderson reported the loss of the Fitzgerald , the search for survivors began. The first search party consisted of the Arthur M. Anderson itself and a second freighter, the William Clay Ford . The use of a third freighter, the Canadian Hilda Marjanne , was thwarted by the weather conditions. The US Coast Guard sent three planes, but initially could not mobilize ships because of the weather. A buoy the Coast Guard, the Woodrush , could run them within three hours, but took more than a day to arrive at the accident. During the search, debris as well as lifeboats and rafts were found, but no survivors.

The wreck

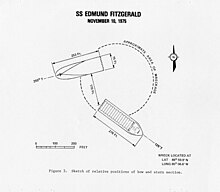

The wreck was first discovered by a US Navy aircraft fitted with a magnetic anomaly detector normally used to detect submarines. The wreck was then examined from November 14 to 16, 1975 with the help of side-sighting sonar by the coast guard. The sonar detected two large objects lying close together at the bottom of the lake. A second investigation was carried out by a private salvage company from November 22 to 25.

From May 20 to May 28, 1976, the wreck was photographed with the help of an unmanned US Navy submersible , which was equipped with a camera vehicle. It is located at 46 ° 59 ′ 54 ″ N , 85 ° 6 ′ 36 ″ W in Canadian waters. The submersible found the Edmund Fitzgerald divided into two large halves at a depth of 160 meters. The bow section, about 84 meters long, lay upright in the mud. The stern was 52 meters away, upside down at a 50-degree angle to the bow. Piles of metal and taconite between the bow and stern formed the remains of the central section.

In September 1980 the research vessel Calypso led an expedition to the wreck under the direction of Jean-Michel Cousteau , which, however, brought little new knowledge. In August 1989 there was another diving expedition with a remote-controlled submersible, led by a team of members from various organizations, including NOAA . This expedition concluded that the damage to the bow was far too great to have been caused by the storm.

On July 4, 1995, the ship's bell was recovered from the wreck and replaced with a replica with the names of all 29 crew members engraved on it. This was the last officially approved dive to the wreck. The Canadian parliament, not least at the instigation of the victims' relatives, passed a law that protects the wreck as a sea grave.

causes

After the disappearance of the Edmund Fitzgerald , it was initially assumed that the effects of the storm had already broken the ship in two on the surface of the lake. Previous ship accidents suggested that the bow and stern sections would be found further apart at the bottom of the lake. However, since the wreckage was later found only a few meters apart, it was concluded that the ship had only broken apart at the bottom of the lake.

An investigation by the Coast Guard came to the conclusion that the accident had been caused by insufficient hatch closures, so that the strong waves could penetrate the hold water. As a result, the hold was slowly and probably flooded over the whole day and unnoticed, which ultimately led to a disastrous loss of buoyancy and stability, so that the ship suddenly sank without warning.

The Coast Guard report met with opposition from many sides. The most popular alternative theory is that the defective radar forced the crew to use inaccurate maps, causing the Fitzgerald to land on a sandbank near Caribou Island unnoticed by the crew . This damaged the underside of the vessel and slowly filled it with water until it suddenly sank without the crew having time to react. The ship screwed itself into the bottom of the lake, broke in two, and the stern landed upside down on the bottom. (Due to the long length of the ship compared to the water depth, the stern could even have been above water when the bow hit the seabed.) This theory is supported, among other things, by the last radio communication between the Anderson and the Fitzgerald ; The Anderson had been hit by two large waves that continued toward the Fitzgerald . However, it is difficult to prove that the hull actually tore before the sinking. The wreck has lodged in the mud up to the loading marks, making further investigation impossible.

A long break edge in the hull armor of the wreck was examined in a documentary produced and broadcast by the television station Discovery Channel . Previous damage to cargo hold covers and strikers as well as material breaks were also discussed. Using wave pools and computer simulations, the television team concluded that the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald was caused by a monster wave . The sea weather reports described three large waves, of which Edmund Fitzgerald had also reported. The investigation therefore concluded that the ship was badly damaged by the first two waves, then water penetrated through the damaged cargo hold covers and the ship was then pushed underwater by the third wave.

Memorials

The day after the sinking, the Mariners' Church in Detroit rang its bell 29 times, once for each crew member who was killed. The church held this annual memorial day for 30 years, when the names of the crew members were read out when the church bell was rung. From 2006, the memorial ceremony was expanded and is now a memorial event for all seafarers who lost their lives on the Great Lakes.

The original ship's bell recovered from the wreck is now on display at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum at Whitefish Point . Since then, a memorial ceremony has also taken place there every year on November 10th with the ringing of the bell and the reading of the names. A Fitzgerald anchor that was lost on an earlier voyage was recovered from the Detroit River and is on display at the Dossin Great Lakes Museum in Detroit. At the museum ship Steamship Valley Camp in Sault Ste. Items on display at Marie , Michigan include a lifeboat (ripped apart by the storm), photographs, a film, and models and paintings.

The Edmund Fitzgerald is the last and largest ship that sank in the Great Lakes, but she is not alone at the bottom of the lake. The Great Lakes have a long history of shipwrecks; since 1878 there have been almost 6000 ship accidents, a quarter of them total losses. Many ships and their crews simply disappeared in the storm. Some underwater protected areas for divers have been established, some of which contain several shipwrecks .

In 2005, efforts were made to erect a memorial in Washington in honor of all seafarers who died on the Great Lakes. A campaign aiming to establish November 10th as “Great Lakes Mariners Day” came to nothing when the House of Representatives ended the practice of giving annual memorial days in 1994.

In 1976 the Canadian folk singer Gordon Lightfoot recorded the song The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald , which deals with the events of the downfall. The song became one of his greatest hits and is still a highlight at his concerts today.

Web links

- SS Edmund Fitzgerald Online

- Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum

- SS Valley Camp museum ship

- The Mariners' Church in Detroit

- US Coast Guard report

- Story of Edmund Fitzgerald in the Detroit News

- Website of the University of Wisconsin-Madison on the sinking of Edmund Fitzgerald

- Website of the American weather agency NOAA about the Edmund Fitzgerald

- Re-examination of the weather conditions at that time by the AMS

Footnotes

- ↑ Graeme Zielinski: Shipwreck overshadowed Fitzgerald's legacy . In: Milwaukee Journal Sentinel . November 10, 2005.

- ↑ a b McCall, Timothy. Event timeline of Edmund Fitzgerald ( Memento of the original from August 3, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . SS Edmund Fitzgerald Online .

- Jump up ↑ Elle Andra-Warner: The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald: The Legendary Great Lakes Disaster . Altitude Publishing Canada Limited, 2006, ISBN 1554390079 .

- ↑ a b c d e NWS Marquette, MI . www.crh.noaa.gov. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ↑ Jenny Nolan: detnews.com . info.detnews.com. Archived from the original on May 6, 2008. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ↑ Information from the Mariner's Church of Detroit about the extension of the ceremony ( Memento from May 11, 2008 in the Internet Archive )