Saint Anthony Falls

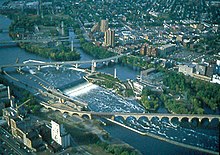

The Saint Anthony Falls (English Saint Anthony Falls or Falls of Saint Anthony ) are located near downtown Minneapolis in the US state of Minnesota . They were to build a weir of concrete that had been erected after the partial collapse of the cases in 1869, in addition to the smaller waterfalls at Little Falls (Minnesota), the only waterfalls in the headwaters of the Mississippi River . Later, during the 1950s and 1960s, a number of dams were built to allow navigation in the section above the falls. The indigenous peoples living in the vicinity of the falls had different names. The Anishinabe they called Kakabikah ( Gakaabikaa , "waterfall over a cliff"), the Dakota used the terms Minirara (" rippling water") and Owahmenah ("falling water"). The cases first became known to the rest of the world in 1680 when the Catholic Belgian missionary Louis Hennepin reported them. This had also brought the news of the existence of Niagara Falls to the world public . Hennepin named the falls after Saint Anthony of Padua . Later researchers who visited and described the falls were, for example, Jonathan Carver and Zebulon Montgomery Pike . The falls and their surroundings were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971 as the Saint Anthony Falls Historic District .

geology

The waterfalls were formed around 9,800 years ago around 12 kilometers downstream at the confluence of the Mississippi and the glacial River Warren at what is now Fort Snelling near the airport . Geologists estimate that the falls were initially around 60 meters high. Since then they have been moving upriver at a speed of about 120 cm annually due to the backward erosion of the limestone layer and reached their current position at the beginning of the 19th century. Tributaries such as Minnehaha Creek formed their own waterfalls after the Mississippi waterfall had receded past its confluence point.

Louis Hennepin estimated the height of the waterfalls to be 15 to 18 meters; later explorers gave five to seven meters. The differences can be due to differences in the extent to which the neighboring rapids have been included. The total gradient of this area is 23 meters across the row of today's dams.

The geological formation of the area consists of a hard, thin layer of limestone overlying a soft sandstone bed. This stratification is the result of an Ordovician lake that covered central eastern Minnesota about 500 million years ago. The boiling water in the impact zone at the foot of the waterfall gnawed the sandstone and washed away the hard top layer, which fell in large fragments.

Industry

The first private land claims on the cases were made by Franklin Steele in 1838 , although it was not until 1847 that Franklin Steele raised the necessary funding of $ 12,000 for a 90 percent stake in the property. On May 18, 1848, US President James Polk approved the claims made against Saint Anthony. Steele was now able to build his dam on the east side of the river above the falls by closing off the eastern arm. The dam jutted into the river at an angle of about 230 meters and was almost five meters high and firmly connected to the river bed. The thickness reached about 12 meters at the base, but only about three and a half meters at the crown. Steele sent logging teams to the Crow Wing River in December 1847 to supply his sawmill with pinewood . On September 1, 1848, his sawmill began working on two vertical saws. He was able to sell his wood already cut and supplied building projects in the up-and-coming city with wood. The new settlement by the falls attracted New England entrepreneurs , many of whom had experience in logging and milling. Steele hired Ard Godfrey to build and run the first sawmill at the falls. Godfrey knew how to most effectively use natural resources , especially the waterfalls and the vast pine forests, to make wood products. Godfrey built the first house in St. Anthony. Steele had done the land registry entry for the town in 1849, the town itself was founded in 1855.

By 1854, 300 occupiers had occupied the west bank of the river, and in 1855 Congress recognized their right to purchase the land they had claimed. The west bank quickly developed into a center of new mills and consortia. They built a diagonal north-facing dam into the river, which, together with the Steeles dam, created the inverted V-pattern that can still be seen today. Steele founded the St. Anthony Falls Water Power Company in 1856 with three associates from New York City . The company struggled to survive for several years, partly because of poor relationships between the financiers, partly because of an economic crisis and because of the American Civil War . In 1868 the company was restructured, now with the participation of John Pillsbury , Richard and Samuel Chute, Sumner Farnham and Frederick Butterfield.

As Minneapolis and its former neighbor, St. Anthony, developed, the falls hydropower became a source of energy for various industries. Water power was used by sawmills, spinning mills, and flour mills . The Minneapolis waterfront mill operators formed a consortium to generate hydropower by diverting river water into vertical shafts equipped with water wheels. These were driven through the hard limestone into the soft sandstone below and led the water back through horizontal tunnels to the river below the waterfalls. These shafts and tunnels weakened the limestone ceiling and the sandstone subsoil and thus accelerated the receding erosion between 1857 and 1868 to eight meters per year. There was therefore a threat that the waterfalls would quickly reach the edge of the limestone ceiling; as soon as the limestone was completely eroded away, the falls would have turned into rapids that were extremely unsuitable for the use of hydropower. The mills on the St. Anthony side were less organized and therefore industry on the east side of the river developed at a slower pace.

Collapse of the Hennepin Island Tunnel in 1869

The first dams, which were built to tame water power, exposed the limestone to the forces of nature by freezing and thawing, narrowing the river and increasing the damage caused by floods. A report in 1868 found that a stretch of just 3350 meters remained before the limestone would be completely eroded away. Then the falls would turn into rapids. In the meantime, the St. Anthony Falls Water Power Company had approved a plan by William W. Eastman and John L. Merriam's company to build a tunnel under the Hennepin and Nicollet Islands that would allow the water to be shared. The realization of this plan led to a disaster on October 5, 1869, when the limestone ceiling collapsed. The leak turned into a raging jet of water that shot out of the tunnel directly onto Hennepin Island, so that a piece of the island about 50 meters long was broken out. Believing the mills and other businesses around the falls would be ruined, hundreds of spectators flocked to the crowd. Groups of volunteers began to build a weir around the hole by throwing trees and wood into it, but these attempts were ineffective. Then they built a large raft from the timbers that were stored at the sawmill on Nicollet Island. This worked briefly, but ultimately also failed. Numerous workers built a dam over months to divert water from the hole. The following year, an engineer from Lowell , Massachusetts recommended that a wooden weir be built, the tunnel filled in, and low dams built around the falls to keep the limestone out of the weather. This work was supported by the federal government and finally completed in 1884. Federal funds spent $ 615,000 on this, and the two cities gave $ 334,500.

Locks and dams

The St. Anthony Falls formed the upper end of commercial shipping on the Mississippi River until two dams and a series of locks were built by the United States Army Corps of Engineers between 1948 and 1963 . The locks made shipping possible above Minneapolis, but because of the smaller size of these locks compared to other Mississippi locks, the practical navigability limit is further downstream. Only a few ships go north beyond St. Paul .

In 1963 the upper dam was completed. It is a horseshoe-shaped dam that serves the hydroelectric power station and is 28 m high. The upper basin has a normal capacity of 3,885,000 m³ and a normal level of 244 m above sea level . The shipping canal required a modification to the historic Stone Arch Bridge , which now has a metal beam section that allows ships to pass underneath.

The lower dam, which is 18 m high and consists of an 84 m long concrete drainage channel with four flood gates , was completed as early as 1956 . The lower basin, sometimes known as the intermediate basin, has a capacity of 463,000 m³ and is 229 m above sea level.

The basin below the lower dam is at a normal height of 221 m above sea level. The upper and lower lock chambers are each 17 m wide and 122 m long.

Although the falls usually don't look very dangerous, the current is strong. Again and again people get into threatening situations. In 1991, for example, a small boat had drifted too close and skidded over part of the dam. Two inmates were killed and two others had to be rescued by helicopter . Most of the rescues at the site are less dramatic but happen fairly regularly.

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ Freelang Ojibwe Dictionary . Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- ^ A b c d Engineering the Falls: The Corps Role at St. Anthony Falls . US Corp. of Engineers. Archived from the original on May 3, 2007. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved May 18, 2007.

- ↑ a b A History of Minneapolis . Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved February 4, 2013.

- ^ Scott Anfinson: Archeology of the Central Minneapolis Riverfront . The Institute for Minnesota Archeology. 1989. Retrieved May 8, 2007.

- ↑ a b St. Anthony Falls: Timber, Flour, and Electricity (PDF; 1.4 MB) National Park Service. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- ↑ 1838: Franklin Steele claims land at the Falls . In: Timeline . Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on May 3, 2003. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- ^ History of the Minneapolis Riverfront District and vicinity . In: Bridges . Minneapolis Riverfront District. Archived from the original on June 20, 2007. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- ↑ Old St. Anthony . In: Mississippi River Design Initiative . University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on June 28, 2007. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- ↑ Lucile M. Kane: The Falls of St. Anthony: The Waterfall That Built Minneapolis . Minnesota Historical Society , St. Paul , Minnesota 1966, revised 1987.

- ↑ Shannon M. Pennefeather: Mill City: A Visual History of the Minneapolis Mill District . Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, Minnesota 2003.

Web links

- ( Page no longer available , search in web archives: US Army Corps of Engineers St. Paul District: Upper St. Anthony Falls ) (English)

- ( Page no longer available , search in web archives: US Army Corps of Engineers St. Paul District: Lower St. Anthony Falls ) (English)

- ( Page no longer available , search web archives: Engineering the Falls: The Corps Role at St. Anthony Falls ) (English) - Article from the Army Corps of Engineers website on the history and geology of the St. Anthony Falls

Coordinates: 44 ° 58 ′ 54 ″ N , 93 ° 15 ′ 31 ″ W.