Antikythera shipwreck

The Antikythera shipwreck is an ancient ship discovered at a depth of about 55 meters in the Mediterranean off the Glyfadia headland (Γλυφάδια) in the northeast of the island of Antikythera . The wreck dates from the 1st century BC. Chr.

Research history

The discovery of the wreck and the first recovery campaign

In the spring of 1900, sponge divers discovered the wreck. The captain informed the responsible ministry about the find and asked for permission to examine the wreck further. The Greek state decided to support the investigations with a ship from the Kriegsmarine . Antonios Oikonomou , a professor of archeology at the University of Athens , received the scientific supervision. The mission began in November 1900. Although it was initially only moderately successful in recovering the objects due to the bad weather, it continued through the winter. The small team of sponge divers was overwhelmed by the frequency of the dives; some of the divers suffered health problems and had to be hospitalized. In the spring of 1901, the government therefore called for greater participation in the diving campaigns and finally entered into a partnership with an Italian company. The salvage campaign lasted until September 1901. This first diving campaign brought the majority of the finds known today to light, but the location of the finds was not mapped at that time, so that many contexts of the find are lost. Some of the fragments were lost because the divers thought the encrusted marble pieces were stones and sunk them in deeper water.

The finds were handed over to the National Archaeological Museum to be cleaned and preserved there. The Greek sculptor Panagiotis Kaloudis and the French artist Alfred André put the statues back together.

The documents related to this campaign are now in the Historical Archives of the Greek Archaeological Service .

The rescue campaigns under Jacques-Yves Cousteau

The Greek government commissioned Jacques-Yves Cousteau , who had already carried out archaeological underwater salvages in Greece several times, with a second diving campaign . He was supposed to find more finds and make a film about his work on the wreck. 1953 Cousteau first dived to the wreck; from June to November 1976 he and his team worked on the research vessel Calypso on the Antikythera wreck. They were now working with better technical equipment: Using a vacuum pipe, they sucked sand from the wreck onto the research ship, from which the smaller finds could be collected. Larger finds were lifted on deck with a crane.

Latest research

In 2012, the State Agency for Underwater Archeology, together with partner institutions, including the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution , launched a new research project on the Antikythera wreck. In autumn 2014, the re-investigation of the wreck began. Used came rebreathers that allow a longer dive to depths below 60 meters, and a diving robots and metal detectors. During the expedition, new finds were recovered from the wreck, including two large bronze spears, presumably from oversized warrior statues, gold jewelry, the only surviving pendulum ram ("war dolphin") and bone fragments from a 15 to 25 year old old man. Since there are even intact skull bones under these, there is hope of a successful DNA analysis, which was carried out by DNA expert Dr. Hannes Schroeder from the Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. DNA traces from the substances stored in the transport containers should also provide further information about the transported goods. The research project not only examines the wreck, but also systematically examines the Antikythera coastline. Ceramic finds that were up to 350 m away from the wreck make extensive research necessary. It is unclear whether the distant finds belong to the same ship or whether other ships capsized at this point.

The ship

The ship was made of oak and elm wood . The planks were joined with bronze nails and partly coated with lead sheet. Peter Throckmorton, who was the first to examine the parts of the ship, determined a length of approx. 30 m, a width of approx. 10 m and a capacity of approx. 300 tons. Since crucial parts of the ship such as the bow, stern and deck have not been preserved, only limited conclusions can be drawn about its construction. The planks that have been preserved are remarkably thick, so the ship was very sturdy. A lot of roof tiles were found in the wreck, probably belonging to the ship and covering part of the deck. A lead pipe is interpreted as part of a drainage system.

14 C dates showed that the trees from which the ship planks were made date back to approx. 220 BC. BC (± 40 years) were felled. If these results are correct, the ship must have been extraordinarily old when it sank. In the case of antique ships, a significantly shorter lifespan can normally be assumed, as the wood showed excessive damage after a few decades.

Finds

Sculptures

Numerous bronze and marble sculptures were found in the Antikythera wreck . The bronze works are unusually well preserved. Among them are originals from the classical and Hellenistic period as well as late Hellenistic classical works and ancient copies .

The so-called young man or Ephebe of Antikythera is a 1.94 meter tall bronze statue and is one of the most famous finds from the wreck. The sculpture was reassembled from many individual parts. It is probably an original from the 3rd quarter of the 4th century BC. It is not possible to assign an artist, although an influence of the Polyklets school can be seen in its design .

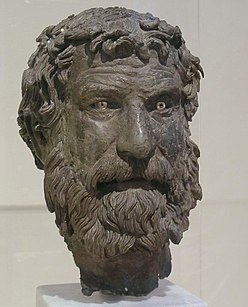

Another well-known work is the slightly larger than life bronze head of a philosopher. It is probably an original from the early Hellenistic period, probably from the last third of the 3rd century BC. The head belonged to a statue, of which the right arm, stretched out in the gesture of speech, as well as the left hand, in which he holds a stick, is preserved. On board were parts of at least three other statues of similar dimensions, including another hand and two feet with sandals, a bronze lyre , which must also have belonged to a statue, and a bronze helmet plume .

Five statuettes can be assigned to the classical, late Hellenistic style. They were not exact copies of classical works from the 5th and 4th centuries BC. BC, but made use of their style elements. The statuettes found in the Antikythera wreck were probably made in the late 2nd century BC. Created.

There were also fragments of 36 sculptures made of Parian marble . They were heavily encrusted with shells and debris; Only the parts that were dug into the seabed are well preserved. Below are two larger than life statues of the god Hermes . One is an antique replica of Hermes Richelieu ; the original, made of bronze, dates from around 360-350 BC. Another corresponds to the type of Hermes Andros-Farnese after a bronze original from around 340 BC. A badly damaged marble sculpture can be identified as a replica of Herakles Farnese by the sculptor Lysipp . Two statues of women probably both show the goddess Aphrodite ; one of them is in the tradition of Aphrodite of Knidos des Praxiteles . A roughly life-size horse statue was also found in the shipwreck. There are also some neo-classical statues from late Hellenism and some late Hellenistic creations, including a small statue of a wrestler and a seated statue of Zeus, as well as a group of statues that are interpreted as the Homeric heroes Odysseus , Philoctetes and Achilles and are among the latest sculptures of the charge. Such statues of mythical heroes were fashionable in Rome at the time of the late republic . They were used to furnish the villas of wealthy Roman citizens.

The uniform material of the marble sculptures suggests a common origin, perhaps even a common workshop. The most recent marble works from the 1st century BC B.C., can only have been made shortly before shipment. On some of the older pieces, including the bronze statues of the philosopher and related fragments, traces of repairs can be seen, which indicate a longer use before transport. Some of the more recent works have bases made of Parian marble.

The Antikythera Mechanism

The most famous find from the wreck is the so-called Antikythera Mechanism . It is a mechanical instrument whose function has been the subject of decades of interdisciplinary research. It is viewed as an astronomical measuring instrument that could have been used for nautical purposes. It is also known as an analog computer. According to the latest findings, the mechanism was probably developed in the 2nd half of the 2nd century BC. Constructed.

Coins

The coins from the Antikythera wreck were discovered in the 1976 campaign. They were clumped together from corrosion . They were separated and cleaned in the National Museum in order to be able to study them, but this partially severely damaged their surface.

Most of the more than 40 bronze coins are too poorly preserved for a closer determination. Of the few that can be identified, two come from Catania , one from Panormos - today's Palermo -, one from Knidos and two from Ephesus . The bronze coins were of little value and were used more for small local transactions. The large geographical range of the places of origin from Asia Minor to Sicily suggests that the ship, or at least its crew, had traveled far.

The 36 silver coins preserved are cistophori . Most come from Pergamon , some from Ephesus. The silver coins also suggest that the ship had previously anchored in Asia Minor, probably in Ephesus. The silver coins can be sold between 104 and 67 BC. To date.

More metal finds

In the wreck there were feet, headrests and other parts of Klinen , which, thanks to their elaborate decoration, must have been valuable pieces of furniture and which, like the sculptures, were probably intended as furnishings for houses of the wealthy Roman population. The cargo included some small silver vessels that were used as exclusive tableware. Some of the simpler metal vessels that were made in the late Hellenistic period were more likely to be part of the crew's everyday dishes.

A small number of gold pieces of jewelry were also found, including an emerald with a gold setting and a pair of earrings, as well as another earring - probably from the same workshop - with colored semi-precious stones and pearls set in gold . It is unclear whether they belonged to women traveling with them or whether - despite their small number - they were loaded as commercial goods.

Ceramics and glass

Most of the fine ceramics found in the wreck belong to the so-called Eastern Sigillata A , the latest variant of Hellenistic ceramics, which was found in the eastern Mediterranean in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. Was widespread. 9-10 vessels of the so-called gray goods - fine ceramics with black, glossy coating and stamp decoration - were also found on board. The dishes obtained consist mainly of plates, bowls and mugs. The vessels of the Eastern Sigillata A can be assigned to three crockery sets. Some plates show signs of use, which suggests that they were used by the ship's crew. However, among the so far uncovered finds of the wreck there are even larger quantities of similar fine ceramics, so that in view of the quantities found it must be assumed that at least parts of the fine ceramics were also part of the trade. Finds of Eastern Sigillata A in Italy show that this commodity was traded there, albeit in small quantities.

Many lagynoi were found in the wreck , a vessel shape that was widespread in the eastern Mediterranean during the Hellenistic period. Most of them are sparsely decorated or completely undecorated, although some specimens have been found with a light-colored coating, which could also have been more elaborately painted. The large number of lagynoi found in the Antikythera wreck suggests that they were part of the cargo, although the vessels themselves were hardly considered to be among the more valuable commodities, but rather their contents. The larger lagynoi served as transport vessels for liquids, often wine. A lot of other bottles and jugs of various shapes and sizes of little value were used to store liquid goods such as wine, perfume or resin.

Among the 21 transport amphorae were specimens from the islands of Rhodes and Kos and from Ephesus, as well as some vessels of the Roman type Lamboglias 2 . Virginia Grace investigated and published the Rhodian transport amphorae from the 1900/1901 campaign . Kos and Rhodes were known for their wine, which was also popular in Rome.

The expedition of 1900/1901 brought to light several, in some cases very well preserved, single and multi-colored glass vessels. Their production sites are believed to be in the Levant and Egypt . The material from the wreck is early evidence of glass trading to Italy.

Everyday objects

Olive stones and snails found in the wreck are likely food residues for the crew. Net sinkers indicate fishing during the trip. Some stone and glass tokens and some lamps may also have belonged to the crew. The lamps were simply decorated, were found only in small numbers and show signs of fire, so they are unlikely to have been intended as commercial goods.

bone

Remnants of 22 human bones and 11 human teeth were found in the wreck. Since there are four right humerus bones underneath, the bones must belong to at least four individuals. The research team identified a young man between 20 and 25 years of age, a young adult woman and, given the well-preserved enamel, a likely adolescent person.

Dating and interpretation

The dating of the most recent coins around 70–60 provides an important basis for dating the wreck. Fine ceramics, especially the Eastern Sigillata , can be traced back to around 60–50 BC. To date. According to Virginia Grace , the manufacturing time for the transport amphorae found in the wreck is likely to fall shortly before mid-century. The other amphora finds from the wreck confirm the dating to this period. The combination of all datable finds shows that the ship was probably built between 70 and 60 BC. Has decreased.

The ship was probably on its way to Italy. It sank off the east coast of Antikythera, so it was probably in the eastern part of the Aegean. The starting point of the trip is discussed. The cargo of goods from different regions of origin, which are distributed over the entire southern and eastern Mediterranean area, speaks for a busy port like Delos or Ephesos, which were supraregional transhipment points at that time.

The question of the origin of some of the works of art invited is also unresolved; In particular, the place of manufacture of the marble sculptures is the subject of a scientific discussion. The fact that all marble statues are made of Parian marble was seen as an indication of an origin from the island of Paros. However, Parian marble was a supraregional coveted material in antiquity. In his examination of the sculptures, Peter C. Bol came to the conclusion through typological comparisons and investigations of the working technique that they came from workshops on the island of Delos . He suspects that the sculptures were created when the island was destroyed in 88 or 69 BC. Were robbed by Delos. Another possible production site for the sculptures is Pergamon. The older works also fit this thesis, since it has been widespread in Pergamon since the time of the Attalids to collect sculptures from different art epochs, so that the older works that were part of the consignment can also be explained plausibly. The range of glassware is similar to that found during excavations on Delos; this in turn supports the thesis of Delos as a transshipment point for at least some of the goods loaded in the wreck.

The way in which the cargo got onto the ship is also discussed. The two main theses represented are that it was a matter of regular commercial goods or stolen goods or spoils of war. It has been suggested that it could have been the booty of Sulla from Athens or the booty of pirates from Melos . The astrophysicist Xenophon Moussas from the University of Athens thinks it is possible that the ship belonged to a convoy that brought booty from Rhodes to Rome for a triumphal procession planned by Julius Caesar . However, the fact that matching bases made of the same material have been preserved for some of the marble statues indicates that these statues were delivered from the workshop together with their base and were not, for example, stolen from their first location. It is more likely that they came fresh from the workshop and were intended for their initial installation. The very good condition of the best-preserved pieces and traces of work on the most recent marble sculptures also indicate that the pieces were new at the time they were shipped and had not been removed from a previous installation. There is convincing evidence that the cargo on the Antikythera shipwreck was a legal item.

Exhibitions

The finds from the Antikythera wreck are still in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens and some of them can be seen in the permanent exhibition. A special exhibition about the wreck took place there in 2012/2013. From autumn 2015 to spring 2016, the finds were shown in an exhibition in the Antikenmuseum Basel .

literature

- Ioannis N. Svoronos : The Athens National Museum. Volume 1. Beck & Barth, Athens 1908, pp. 1–86 ("Die Funde von Antikythera") (online)

- Gladys Davidson Weinberg, Virginia R. Grace, et al. a .: The Antikythera shipwreck reconsidered. (= Transactions of the American Philosophical Society NS 55, 3) American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia 1965 (on the ship and its dating, to be dated to 80-50 BC after the finds).

- Peter Cornelis Bol : The sculptures of the Antikythera ship find. (= Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Athenian Department Supplement 2). Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-7861-2191-5 (on the sculpture finds from the ship's find).

- Nikolaos Kaltsas , Elena Vlachogianni, Polyxeni Bouyia (eds.): The Antikythera Shipwreck. The ship, the treasures, the mechanism. National Archaeological Museum, April 2012 - April 2013 . Kapon, Athens 2012, ISBN 978-960-386-031-0

- Andrea Bignasca (ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck. Publication accompanying the exhibition September 27, 2015– March 27, 2016 . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8

Web links

- Website of the Greek Ministry of Culture and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution on the Antikythera shipwreck with information and images on all aspects of the ship's find

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Metaxia Tsipopoulou, Maria Antoniou, Stavroula Massouridi: The investigations of the years 1900 and 1901. In: Andrea Bignasca (ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , pp. 66–97.

- ↑ a b c d Elena Vlachogianni: Sculpture. In: Andrea Bignasca (Ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , pp. 106–135.

- ^ Lazaros Kolonas: The Investigations of 1976. Memories of the collaboration with Jacques-Yves Cousteau in Greece. In: Andrea Bignasca (Ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , pp. 80–85.

- ↑ a b Jo Marchant: The decryption of the sky . Rowohlt, 2011, ISBN 978-3-4980-4517-3 .

- ↑ a b c Breandan Foley, Theotokis Theodoulou: Return to Antikythera. In: Andrea Bignasca (Ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , pp. 234–243.

- ↑ Zacharias Zacharakis: Journey to the last riddle of the original computer. Zeit Online , September 29, 2014, accessed October 31, 2014 . Jan Dönges: Antikythera wreck. Research divers test exosuit. Spectrum , October 9, 2014, accessed October 31, 2014 . Terrence McCoy: Scientists uncover more secrets from Antikythera's 'Titanic of the ancient world'. The Washington Post , October 10, 2014, accessed October 31, 2014 . Lauren Said-Moorhouse: Lost treasures reclaimed from 2,000-year-old Antikythera shipwreck. CNN , October 10, 2014, accessed October 31, 2014 .

- ↑ a b BBC News - Antikythera wreck yields new treasures

- ↑ Jo Marchant: A skeleton in the Antikythera wreck. spectrum.de, September 20, 2016, accessed on October 21, 2018 .

- ↑ a b c d e Polyxeni Bouyia: The ship. In: Andrea Bignasca (Ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , pp. 86–93.

- ↑ Yanis Bitsakis: The Antikythera Mechanism. In: Andrea Bignasca (Ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , pp. 222–233.

- ↑ a b Panagiotis Tselekas: The coins. In: Andrea Bignasca (Ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , pp. 214–221.

- ↑ a b Nomiki Palaiokrassa: Objects and devices made of metal. In: Andrea Bignasca (Ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , 136-147.

- ↑ a b c Elisabeth Stassinopoulou: Gold jewelry and silver vessels. In: Andrea Bignasca (Ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , pp. 158–163.

- ↑ a b c d George Kavvadias: Fine ceramics with a red glossy coating. In: Andrea Bignasca (Ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , pp. 178–187.

- ↑ a b George Kavvadias: Fine ceramics with black glossy coating (gray goods). In: Andrea Bignasca (Ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , pp. 188–197.

- ↑ Evangelos Vivliodetis: The Lagynoi. In: Andrea Bignasca (Ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , pp. 164–171.

- ↑ Maria Chidiroglou: Jugs, single-handled bowls, sieve bottles, Olpen and unguentaries. In: Andrea Bignasca (Ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , pp. 198–205.

- ↑ a b Dimitris Kourkoumelis: The transport amphorae . In: Andrea Bignasca (Ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , pp. 206-213.

- ↑ Christina Avronidaki: The glass. In: Andrea Bignasca (Ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , pp. 148–157.

- ↑ Anastasia Gadolou: Life on Board. In: Andrea Bignasca (Ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , pp. 94–99.

- ↑ Evangelos Vivliodetis: The lamps. In: Andrea Bignasca (Ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , pp. 172–177.

- ↑ Argyro Nafplioti: The human bone material. In: Andrea Bignasca (Ed.): The sunken treasure. The Antikythera shipwreck . Antikenmuseum Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-9050-5734-8 , pp. 100-105.

- ↑ Ancient 'computer' starts to yield secrets. iol scitech , June 7, 2006, accessed November 1, 2014 .

Coordinates: 35 ° 52 ′ 56 ″ N , 23 ° 18 ′ 57 ″ E