Sponge beetle

| Sponge beetle | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

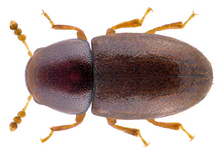

Cis boleti , the first described sponge beetle, 2.8 to 4 millimeters |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Ciidae (Cisidae) | ||||||||||||

| ( Leach , 1819) |

The sponge beetles (Ciidae, formerly Cisidae) form a family of beetles that is widespread worldwide and , together with 28 other beetle families, is part of the tenebrionoid superfamily . The family is relatively poor in species within Europe and fairly uniform in terms of structure and biology. Around 600 species in 40 genera are currently described worldwide , but it is estimated that there are still hundreds of undescribed species, mainly from Asia and Central and South America.

Notes on names and synonyms

The sponge beetles live mainly in the fruiting bodies of fungi on trees. These are also called tree sponges , the Ciidae also hard mushroom beetles or tree sponge eaters (not to be confused with the tree sponge beetles ). The scientific name of the family is derived from the generic name Cis , most of the species in the family belong to the genus Cis . C sharp is from old gr. κις "kis" derived for "woodworm". Numerous generic names within the family also contain the syllable -cis- as a stem.

As a family, the Ciidae are classified as Cisidae as early as 1819 in an English book by Samouelle based on manuscripts by Leach . That is why Leach 1819 in Samouelle is mentioned in detail as the author of the family , but mostly in connection with the family name in the spelling Ciidae. In 1854 Wollaston used the spelling Cissidae, Gistel in 1856 the spelling Cioidae. The spelling Ciidae is first used by Marseul in 1857 . Marseul notes the abbreviation Mll Soc 49 directly after the name Ciidae. 213. According to the abbreviation system explained by Marseul himself, the abbreviations for Mellié are in Annales de la Société de France, year 1849, p. 213 . The context shows that this is the year of 1848. In the corresponding article Mellié defines different genres of the family, but does not name the family itself and expressly emphasizes that he does not want to comment on family membership. He explains je ne m'occuperai pas ici de savoir, à quelle place le (s) genre (s) ..... devront être rangé (s) ( fr. I'm not trying to know where the genre (en ) ..... should be classified (s) ). So Marseul does not take the spelling of the family name from Mellié.

The extent to which the spellings Cisidae, Cissidae, Ciidae and Cioidae can be traced back to misprints, to different views on the linguistically correct derivation of the family name from the generic name or to a deliberate change due to a new delimitation of the family members cannot be traced back to the sources listed here decide. If you derive the family name from the root ki of the genitive form kios to the word kis , the spelling Ciidae is correct. In German-speaking countries, the term Cisidae is traditionally used, as it corresponds to the priority rule . In older writings, the three spellings Cisidae, Cioidae and Ciidae are represented fairly equally, in the Biodiversity Heritage Library the hits for all three names are between 419 and 470. But the beetle system, which is also used in Wikipedia, is used in more recent literature the spelling Ciidae through. Other synonyms are Cissidae, Orophyidae and Octotemnidae, but they are not in use.

Notes on the history of demarcation and classification of the family

The first species that belongs to the family was described by the Austrian Scopoli in 1763 under the name Dermestes boleti . The genus name Cis appears for the first time in 1796 at Latreille , who split off the new genus from the genus Dermestes .

In 1819, Leach divided all beetles into four sections (corresponding to the number of tarsi members) and a total of 53 families. He puts the sponge beetles as the 39th family between the families Bostrichidae and Mycetophagidae, which he also established . At Leach, the family includes two other genera in addition to the genus Cis , which are now placed in other families.

The first major revision of the family began in 1848 with the French work Monographie de l'ancien genre Cis des auteurs (for monograph of the former genre Cis by different authors ) by Mellié . The main features of this monograph were read out and recorded in the form of a letter from Mellié at a meeting of the Entomological Society of France as early as 1847. The monograph is intended to help Mellié in his endeavors to become a member of the Entomological Society of France. In the monograph, Mellié sorts species that have been at least temporarily assigned to the genus Cis by various authors , according to previously disregarded characteristics and divides them accordingly into different genera. He describes the species again and in detail, sorted according to these properties, and he adds numerous initial descriptions. He divided 93 species into seven genera ( Endekatomus , Xylographus , Rhopalodontus , Cis , Ennearthron with the subgenus Ceracis , Octotemnus and Orophius ). Almost all of the genres have been reorganized by him; he only finds the name Xylographus (without a description) in Dejean's collection and he takes over the name Orophius from Redtenbacher for part of the genus he planned in 1847 under the name Octotemnus , the Redtenbacher has since published under the name Orophius . Mellié counts 62 species in the genus Cis . Mellié only lists thirteen species as an appendix, which he only knows from descriptions but was not able to examine himself in the corresponding collections.

In 1857 Lacordaire defined the Ciidae family in the form of writing Cissidae, in which he took over all genera from Mellié, upgraded the subgenus Ceracis to the genus and incorporated the species of the genus Lyctus into the family. Lyctus and Endecatomus (also spelled Hendecatomus ) are soon separated from the Ciidae by Du Val as a separate family Lyctidae (today the subfamily Lyctinae of the drill beetle ).

With this definition of the sponge beetles Abeille de Perrin published in 1874 a compilation of the Ciidae occurring in Europe and around the Mediterranean. Since the genus Ceracis does not occur in Europe and Orophius is only used for one species from Sweden, the species listed belong to the genera Xylographus , Rhopalodontus , Cis , Ennearthron in the narrower sense and Octotemnus . Perrin divides the species Cis alni of Mellié into five species ( Cis alni , C. perrisi , C. coluber , C. lucasi and C. reflexicollis ), adds some species from other authors and also describes six new species that occur in the area ( Cis nitidicollis , C. libanicus , C. peyronis , Rhopalodopus baudueri , Ennearthron filum and E. reichei ). In a supplement, Perrin describes a seventh new species, Rhopalodopus camelus . Perrin counts 52 species for the family in France and around the Mediterranean. It places the family between the Scolytidae and the Tomicidae. Both families are now counted among the bark beetles .

The catalog of European beetles in 1906 lists 59 species of the Ciidae in 7 genera (without end decatoms ). In 1911 , Dalla Torre lists 334 species in 20 genera worldwide (not including end decatomes ).

More recent studies show that the European species of the family are almost completely known. Rose found 53 species for continental France and Corsica in 2012, including no species that has not yet been described. In his 1999 work on the cisids of southwest Germany, Reibnitz also lists only 40 species, among which there are no new species. In contrast to Perrin and Mellié, who only describe the imagines of the species in detail, the works by Rose and von Reibnitz contain a wealth of data on the history and biology of the family and the species, for example the host fungi. Reibnitz relies on a close-knit network for the find data, which makes the occurrence in sixteen large natural areas of south-west Germany comparable and evaluates the find data from more recent points of view, for example recording population densities and indicating height distributions.

The genera show a different picture. While Perrin divides his 52 species into five genera, Reibnitz assigns eight genera to the 40 species of southwest Germany, and Rose divides the 53 species of France into thirteen genera. This is due to the fact that the worldwide coverage of the Ciiden has taken an upturn, especially in recent times. Lawrence describes 84 species in twelve genera for North America (excluding Mexico ) in 1971 . Numerous new species are also described in Asia, particularly Japan. Due to the rich material, traditional genres (especially Cis ) are split up, subfamilies are introduced and the differentiation from other families is discussed again. The genera Rhipidandrus , Pterogenius and Sphindocis are considered part of the family by some authors, but not by others. In 1971 Lawrence gave about 550 species in forty genera for the world ; in 2008, 640 species were given. It is estimated that there are still several hundred undescribed species in Asia, Central and South America in particular.

In 2017, Lawrence described 75 species from Australia , 56 of which are new. Lawrence calls the work provisional, since he already announces about fifty other undescribed species.

The classification of the family within the beetle was originally based on the external structure of the beetle. According to this, the family was classified in various places within the Bostrichoidea . Later the family was temporarily assigned to the superfamilies Cucujoidea and Cleroidea , because one oriented one-sidedly to the structure of the larvae, the skin wings or the sexual organs. When all the characteristics are taken into account, it seems that it belongs to the Tenebrionoidea most likely today. Within this superfamily, the sponge beetles belong to the more primitive families.

Characteristics of the beetle

Since the genus Sphindocis differs in several characteristics from the other Ciidae, which is why not all authors count it as part of the family, and is also not represented in Europe, the characteristics of the genus are not considered in the following.

The beetles have a more or less cylindrical shape, short cylindrical (oval in plan view) to elongated cylindrical. This makes it easier for them to move through the passages inside the mushrooms. They are usually small to very small, a maximum of six millimeters, usually two to three millimeters, but they can also be only about half a millimeter long. With very few exceptions, they have inconspicuous colors from light brown to black. The animals are bald or protruding, scaled to hairy.

The head is at least slightly tilted and closes tightly to the pronotum . The feelers are pivoted far apart. They are eight to ten links and end in a two to three link club. The limbs of the club have at least four raised areas with sensory hairs (en sensillifers, fr ampoules à trichoides). The eyes are round and prominent. The head shield is set off by a seam. The upper jaws are short, wide with a two- tooth tip. The jaw probes are four-part, the lip probes three-part, both end with a cylindrical to spindle-shaped part.

The pronotum is about the same length as it is wide to a little wider, at the base about as wide as the base of the elytra. In some species, tooth-shaped or horn-shaped projections are formed in the male on the front edge of the pronotum and / or on the head shield.

The wing covers have narrow epipleurs that almost reach the wing tip. The elytra are dotted. As a rule, the points are not arranged in rows. The veining of the skin wings is reduced. The skin wings are rarely missing.

The anterior hip cavities are not closed inwards. The tarsi are almost always all four-membered, only a few North American species have the tarsi formula 3-3-3. The claw link is greatly enlarged, longer than the first through third links together. The claws are not split or toothed, but simple. The trochanter completely separates the hip and thigh.

On the underside of the abdomen, five abdominal sternites can be distinguished. All five are movable against the neighboring segments. The male's first abdominal segment often has a hairy organ for the release of sex hormones. It is in the shape of a dimple and its appearance can be an important determinant.

The male sexual apparatus is very characteristic. The parameters form a common sclerotized plate, which is bent over on the long sides , which more or less encloses the penis and forms a joint with the base of the penis. This record is called Paramerenplatte in German-speaking countries, while Lawrence calls it Tegmen. Their shape differs very clearly in the various species (numerous illustrations in Lawrence). The safe separation of some species is only possible with the help of the parameter plate.

The distance between the front, middle and rear hips, the ratio of length to width of the breast sternite, the way in which the front chest is formed between the front hips towards the rear (prosternal process), the formation of the Lateral margin on the pronotum and the apical formation of the anterior splint

Characteristics of the larvae

The larvae are also built quite uniformly. They are sparsely thin and have long hair. The three breast and nine abdomen segments are approximately the same size and roughly cylindrical. The last abdominal segment ends in two appendages and / or has specific forms on the upper side. The tenth abdominal segment is transformed into an anal foot. The breathing openings of the eighth abdominal segment are small and circular.

There are usually three to five individual eyes on each side of the head, in rare cases two, one or none. The antennae are very short, two-parted, the terminal part is provided with a long hair and a sensory appendix. The jaw probes are tripartite.

The legs are short and the hips are relatively close together. Each claw has two bristles.

The form of the attachments of the last body segment (Urogomphi) is mainly used to determine this, but also the different degrees of sclerotization of the last three body segments.

biology

Habitats

Almost all species live and develop inside the fruiting bodies of tree sponges. By far the species that live in tough to hard fruiting bodies outweigh those that prefer softer fruiting bodies. Some species also occur in fungal bark or wood. Few species are found in places that at first glance have nothing to do with fungi, for example in the bores of bark beetles or in the bundles of brushwood that are produced as waste in the cultivation of vineyards. These species probably also feed on fungal mycelium , perhaps on molds , rust fungi or mildew pathogens .

Each type of beetle usually uses several types of fungus as hosts, conversely, the types of tree sponges are usually colonized by several types of sponge beetles. For example, six species belonging to the sponge beetle were drawn from the tinder fungus Fomes fomentarius near Moscow from 102 identified beetle species. Conversely, the sponge beetle Ennearthron cornutum uses about thirty different types of mushrooms for breeding. However, the beetles show preferences regarding their hosts. Various groups of preferred hosts have emerged.

In North America, over 100 species of fungus are used as hosts by sponge beetles. Apparently, at least some species of sponge beetle produce pheromones that attract conspecifics regardless of gender. Occasionally over a thousand individuals of a species are found in one fruiting body, but there are hardly any individuals of the species on neighboring fruiting bodies ( aggregation ).

It should be mentioned here that there are also other beetle families whose species mainly develop in fungi, for example the tree sponge beetle. This is already expressed by the scientific name of this family, Mycetophagidae (from ancient Greek μύκης mýkes, mushroom, and φάγος phágos, eater).

Ecological connections

According to their demands on the habitat, the species are classified according to different criteria. Regarding the temperature, there are on the one hand species that can be found in both warm and cool environments ( euryöke species, e.g. Cis boleti ,) on the other hand species that only prefer a narrow temperature range (stenoke species). The same applies to the humidity, Ennearthron cornutum , for example, prefers a drier environment. Each species can also have its own tolerance range for tanning the host fungus.

With regard to specialization in food sources, one can distinguish between three groups. On the one hand, there are species that are only found on one type of mushroom (monophag, e.g. Rhopalodontus perforatus ), most species occur on a few types of fungus (oligophag), whereby the host fungi are usually more closely related. Few species use a broad spectrum of host fungi (polyphagous, for example Ennearthron cornutum ). In a publication about sponge beetles in the subtropical rainforest of South America near São Francisco de Paula , forty species of mushrooms are listed. Of the 21 species of Ciidae found on it, only one is classified as monophagous, six as oligophagous and six as polyphagous. Polyphage species also use fungi as hosts, which are only largely related to one another. The host selection for polyphagous sponge beetles is not (only) determined by the degree of relationship between the host fungi, but largely by the properties of the fruiting body (hardness, density and type of branching of the mycelium).

Regarding the time of colonization, there are species that colonize the host at an early point in time when spore formation has not yet started. Other species appear later on the fungi, and most only when the fungus has already completed spore formation, has partially or completely died and is regressing. In America, for example, cis fuscipes are very often found on the reddening tangle of leaves in October when spore formation begins , whereas in the following March, when spore formation subsides, Cis subtilis . Ennearthron cornutum colonizes the host fungi even later, when the fruiting bodies have already partially died. Some species only occur in perennial fruiting bodies. The aging stages of the mushrooms are defined differently by different authors. Among all fungal eaters, the sponge beetles belong predominantly to the secondary fungal eaters (colonists of fruiting bodies with largely complete spore formation), a few species to the primary fungal eaters.

In addition, the species can still be differentiated according to whether they prefer soft or hard fruit bodies, whether they live in the trama or in the hymenophore of the fruit body or in the fungal mycelium in the wood, whether they show short or long development times.

The quantity hypothesis applies to all the insects that develop in the fruiting bodies of mushrooms. It says that the more pronounced the insects are polyphagous, the less predictable the availability of fruiting bodies of a host fungus species is. The fruiting bodies of most mushrooms, especially the agaric mushrooms, are relatively short-lived and their occurrence is rather sporadic. In agreement with this hypothesis, most mycetophages , namely the flies that develop on short-lived fruiting bodies , especially of the genus Drosophila , are polyphagous. In addition, due to the short life of the mushrooms, they also have short development times.

However, the occurrence of tree sponges in temperate climates is relatively easy to predict. It is clocked by the annual rhythm, a fungal tree usually forms fruiting bodies for several years, tree sponges are common in near-natural forests with a high proportion of dead wood, the fruiting bodies are relatively long-lived and are still available as a source of food even after they have died, some tree sponges are even perennial. According to the hypothesis, one can expect mainly oligophagous species among the sponge beetles, and this is also confirmed at least for Europe and North America. In addition, the long-lived fruit bodies also allow longer development times. However, other environmental constraints arise. The beetles are exposed to the metabolic products of the fungus, some of which can prove to be deterrent, inhibitory or poisonous. It is therefore not surprising that the oligophagic sponge beetle species usually find their hosts among closely related fungal species, in which similar metabolic products and defense mechanisms can be assumed.

Assuming that such antibodies / toxins have established themselves evolutionarily mainly because they protect the spore formation, one can assume that their effect at least weaker after the spread of the mature spores and the death of the fungus. If the fungus colonizes late, the beetle is only exposed to the antibodies in at least a weakened form. This would explain why the majority of the sponge beetles belong to the late colonists. In particular, the few polyphagous sponge beetle species , such as Ennearthron cornutum , usually colonize their host fungi at a particularly advanced stage of regression. This opens up a broader and therefore more stable food supply.

The polyphagous sponge beetle species contradict the quantity hypothesis to a certain extent. Hanski shows, however, that polyphagia can not only be achieved by temporarily bypassing the effectiveness of the antibodies, but that a combination of resistances against several types of fungi can quickly develop into multi-resistance. This mechanism probably works in the mycetophagous flies.

Comment fights

The use of the special formations on the breast and head shields of the males of some species in rival fights was analyzed for some species. Reactions of the females regarding the selection of victorious males or males with more imposing skeletal outgrowths were not observed. No damage was found either ( comment fight ). Through the fighting, the more skilled fighter only displaced the enemy.

In Ceracis cucullatus , the male has broad, relatively short growths that are concave in front on the head shield and breast shield. When attacked, the male lowers his head. As a result, the outgrowths of the head shield and breast shield are so far apart that they encompass the abdomen of the opponent like a horizontally opened slide in order to keep pushing the opponent away from you. Head-to-head fights are only exceptionally observed in this species and are not very violent or uniform. With jerky movements, the attackers occasionally attach their opponents to the wall of the feeding passage for hours.

In the form of Cis taurus , the males on the head shield have two broadly separated, forward-facing horns that form a fork. The breastplate shows no special features. The attacks are limited to pushing the horns under the opponent and levering him out with a series of jerky upward movements of the head. These movements are performed both in head-to-head positions and when attacking the abdomen. The leg position is hardly changed, only rocking movements back and forth.

Males from the form of Ceracis furcifer (only) have a forked horn on the head shield, which is usually carried upright. Here, too, the attacker lowers his head, causing the tip of the horn to point forward. Attacks on the opponent's side or from behind try to bring the horn under the opponent and to make him flee with a series of jerky blows on the underside of the opponent. Head-to-head fights are usually fierce, with males trying to push each other away.

In the Cis tricornis form , the males have a central horn on the head shield and two appendages on the pronotum that form a fork pointing forward. The males also lower their heads when attacking and try to push the opponent away in various ways. More or less randomly, this leads to a head-to-head position. In this position the fighters try to push, push away or hit the opponent with unchanged foot position.

Reproduction

In addition to the already mentioned mass accumulations of some sponge beetle species (aggregation), which of course also improve the ability to reproduce, a special attraction of the females was observed, which is caused by a pheromone that the males produce. In Xylographus contractus it was observed that the males are already on the surface of the fruiting body before copulation, while the females are still inside the fruiting body. The males rub the abdomen on the surface of the fungus. Presumably this causes the distribution of the attractant that emerges through the pore on the first abdominal segment. In the experiment it was shown that this substance attracts the females, but not the males. The females leave the fungus for copulation. The excretory organ of the pheromone in Xylographus contractus is a small, hairy pit of the first abdominal sternite. Since many species of sponge beetle have a similar organ, female attraction is likely to be a more general phenomenon.

Eggs are usually laid over a long period of time, so generations can overlap. As far as is known, the eggs are deposited individually or in pairs in a chamber that the females create next to the feeding tunnels, and the chambers are then closed with mycelium. The larvae eat their way from the chamber through intact tissue and pupate in a chamber at the end of the feeding passage near the surface.

Cis nitidus takes about four months to develop at room temperature. Hadraule blaisdelli needs a little over two months at room temperature to develop from an egg to a finished beetle. In Central Europe, both beetles and larvae usually overwinter. Newly hatched beetles of the most common species can be found from spring to autumn. The stages of development in Central Europe are therefore not tied to the annual cycle.

A specialty is the species Cis fuscipes , which reproduces parthenogenetically . The development of the unfertilized eggs takes about 60 days and only yields females.

Economical meaning

Since the sponge beetles are predominantly late colonists, their role as both spreading spores and destroying spores is rather insignificant. The extent to which the beetles influence the natural breakdown of deadwood by damaging the wood-decomposing fungi or by spreading these species is hardly relevant.

The beetles are often attracted by the scents of the host fungi, some species are up to 1.5 km away. Some species, attracted by the scent, can become harmful to commercially used dried mushrooms. Hagstrum lists eight species of sponge beetles that have been identified as storage pests. Cis multidentatus has been found in tofu.

distribution

The family is distributed over all continents except Antarctica and the sponge beetles are found in all tropical to temperate climates.

Looking at the distribution of the individual species, species with a small area of distribution are rather rare, for example Ennearthron abeillei only occurs in southern France and Corsica. Most species have a wide range. The 84 North American species are predominantly restricted to the north (en northern fauna), the south-west (en southwestern fauna) or the south-east (en southeastern fauna), with the last region still being divided into three sub-regions. But one can also find species that are distributed throughout North America (e.g. Octotemnus laevis ). In Europe there are species with a southern European distribution, species that occur in the higher regions of all of Central Europe, and species that are restricted to another part of Europe. But there are also species with a European, Palearctic or even Holarctic distribution. The same applies to other continents.

In order to be able to draw conclusions about the history of expansion, the zoogeographical distribution of the genera is also considered. Even with the genera, the size of their distribution area fluctuates enormously. With regard to small areas of distribution, the subfamily Sphindociinae, consisting of only one species, is an extreme case. It occurs only in parts of California . The genus Apterocis is only found in Hawaii . Cisarthron only includes the species Cisarthron laevicolle , which is restricted to Bosnia , Herzegovina and the Middle East . The genus Cisdygma is restricted to the species Cisdygma clavicorne with the distribution area Greece , Cyprus and the Middle East. The species of the genus Diphyllocis can only be found in southern Europe. The genus Wagaicis only includes the species Wagaicis wagae , which occurs in Europe without southern Europe with a discontinuous east-west distribution. For some genera, the name already allows conclusions to be drawn about the distribution area, the genus Nipponapterocis is restricted to Japan and Atlantocis is only found on the Canary Islands and Madeira .

The genus Strigocis , which occurs with currently only five species in Europe, North America, Mexico and Japan, forms an extreme with regard to an unexpectedly wide distribution . Of the genera not yet listed that are also present in Europe, the genus Cis and Orthocis is distributed almost worldwide. Dolichocis Hadreule and Sulcacis are Holarctic genera. Also Ennearthron is holarctic used, but a kind of comes in Brazil. Rhopalodontus and Octotemnus are not only found in the Holarctic, but also in the Orient and the Australian region, but are absent in Central and South America (Neotropical Region) and in Africa south of the Sahara (Ethiopian Region). Xylographus is distributed worldwide in the tropical and subtropical zones. Overall, the distribution of species and genera shows a rather confusing picture and is only shown here in examples.

Human-induced spread is known for some species, for example the introduction of Cis chinensis to Europe, the USA and Brazil. Cis chinensis is now almost cosmopolitan. The introduction of Cis bilamellatus is well documented . The species was brought from Australia to the southeast corner of Great Britain in the mid-nineteenth century, presumably in a herbarium . By 1960 it had spread west to Wales , south to the Isle of Wight and about 300 km to the north. Cis fuscipes were introduced from North America to Cuba, Hawaii, Madeira, Australia and New Zealand.

Selection of European genera and species (alphabetical)

- Atlantocis

- Cis

- Cisarthron

- Cisdygma

- Diphyllocis

- Doliochocis

- Ennearthron

- Hadreule

- Octotemnus

- Orthocis

- Rhopalodontus

- Strigocis

- Sulcacis

- Wagaicis

- Xylographus

Individual evidence

-

↑ a b

Rolf G. Beutel, Richard AB Leschen: Handbuch der Zoologie - Coleoptera, Beetles, Volume 1: Morphology and Systematics (Archostemata, Adephaga, Myxophaga, Polyphaga partim) . 1st edition. de Gruyter , 2005, ISBN 3-11-017130-9 (English). Richard AB Leschen, Rolf G. Beutel, John F. Lawrence: Handbuch der Zoologie - Coleoptera, Beetles, Volume 2: Morphology and Systematics (Elateroidea, Bostrichiformia, Cucujiformia partim) . de Gruyter, 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-019075-5 (English).

-

↑ a b c d e f g h i

John F. Lawrence, Cristiano Lopes-Andrade: 11.4 Ciidae Leach in Samouelle, 1819 in Coleopterists Bulletin 2010

Number of species known in 2010 p. 504 ; Distribution p. 504f; Biology p. 505f; Morphology of adult and larva p. 507ff -

↑ a b c d e f g h i j

Johannes Reibnitz: Distribution and habitats of tree sponge eaters in southern Germany (Coleoptera, Cisidae) reports from the Stuttgart Entomological Association, year 34, 1999

tolerance range p. 6 ; Brood fungi of Cis nitidus p. 14 tab. 5; German names for the family and belonging to the superfamily Tenebrionidae p. 3; Development time of Cis nitidus p. 5 -

↑ a b c

George Samouelle. Entomologist's useful compendium; or an introduction to the knowledge of the British insects, ... according to the views of Dr. Leach London 1819

as the 39th family, p. 206 ; Formation of family names p. 6 - ↑ a b Sigmund Schenkling: Explanation of the scientific beetle names (genus)

- ↑ a b c d e f Margaret K. Thayer, John F. Lawrence: 98. Ciidae Leach in Samouelle, 1819 in Ed. Ross H. Arnett, JR, Michael C. Thomas, Paul E. Skelley, J. Howard Frank American Beetles Volume 2 CRC Press 2002 Synonyms p. 403 in the Google book search

- ↑ T. Vernon Wollaston: Coleoptera Maderensia London 1854 31. Family p. 17

- ↑ Johannes Gistel: Pleroma on the mysteries of the European insect world with a systematic list of butterflies and beetles in Europa's Straubing, 1856 p. 156

-

^

Sylvain Auguste de Marseul: Catalog des coléoptères d'Europa Paris 1857

notation Ciidae p. 107 ; Explanation of the abbreviations p. V ff -

↑ a b c d

J. Mellié: Monograph de l'ancien genre Cis des auteurs in Annales de la Société entomologique de France série 2, Tome 6, Paris 1848

pp. 205-274 and 313-396 ; Wish to become a member p. 205; Adoption of the name Xylographus from Dejean's catalog and the timing of its publication, its published announcement and the publications of Redtenbacher p. 207f; Disinterest in systematic position p. 209; Partial adoption of the generic name from Redtenbacher p. 381

Compilation p. 394 -

↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l

JF Lawrlence: Revision of the North American Ciidae (Coleoptera) Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoologie Vol 142, No. 5 pp 419-522

Ciidae pp 419-522 ; Historical review, delimitation of the family p. 425f; Description Imago and Larve p. 427f; Historical classification of the family p. 228; Correct spelling p. 432; Fauna areas of North America regarding Ciidae p. 433; over 100 host fungi in North America p. 435; Distribution maps , for Octotemnus laevis map no. 110, p. 522; Number of species and genera described worldwide and in North America in 1971; Hosts of Cis fuscipes p. 460, of Cis subtilis p. 476, of Hadraule blaisdelli p. 491; Tegmen of Aedeagus p. 519 Figs. 68-84 - ↑ Frequency of spellings at BHL, queried on Nov. 16, 2017 419 hits for Cioidae , 443 hits for Cisidae , 470 hits for Ciidae

- ^ Ioannis Antonius Scopoli: Entomologia Carniolica ... Vienna 1763 p. 17 No. 44

- ↑ Pierre André Latreille: Précis des caractères génériques des insectes Paris year 5 of the republic ( i.e. 1796 or 1797) p. 55 genus no.95

- ^ Under Mélanges et Nouvelles ( Miscellaneous and News ) by Guérin-Méneville, Mellié's draft for the monograph of the genus Cis in Revue Zoologique par la Société Cuverienne Volume 10, Paris 1847 Letter from Mellié pp. 108-110

- ↑ Lacordaire : Histoire naturelle des insectes - Genera des Coléoptères 4th volume, Paris 1857 p. 553 Ceracis becomes a genus

-

^

Jacquelin Du Val: Genera des Coléoptères d.Europe 3rd volume Paris 1859-62

synopsis in the Google book search; (H) endecatomus in Lyctidae in the google book search - ^ Elzéar Abeille de Perrin: Essai monographique sur les Cesides européens & circaméditerranéens Marseille 1874 Summary p. 96ff in the Google book search

- ↑ Elzéar Abeille de Perrin: Note sur les Cisides européens et circaméditerranéens in Annales de la Société de France p. 309ff

- ↑ LvHeyden, E. Reitter, J. Weiss: Catalogus Coleopterorum Europae, Caucasi et Armeniae Rossicae Berlin, Paskau, Caen f 1906 S. 349th

- ↑ KW von Dalla Torre: Cioidae in W. Junk, S. Schenkling: Coleopterorum Catalogus pars 30, Berlin 1911 at BHL

- ↑ a b Olivier Rose: Les Ciidae de la faune de France continentale et de Corse mise à jour de la clé des genres et du catalog des espèces (Coleoptera, Tenebrionoidea) in Bulletin de la Société Entomologique de France 117 (3), 2012: 339-362 p.352

- ↑ Gerda Buder, Christin Grossmann, Anna Hundsdoerfer, Klaus-Dieter Klass: A Contribution to the Phylogenie of the Ciidae and its Relationships with other Cucujoid and Tenebrionoid Beetles (Coleoptera: Cucujiformia) , in Arthropod Systematics & Phylogeny 66 (2) 165-190 , eISSN 1864-8312, December 5, 2008 [1]

- ↑ John F. Lawrence: The Australien Ciidae (Coleoptera: Tenebrionoidea) - A preliminary revision Zootaxa, Vol 4198, No 1 Abstract

- ↑ Heinz Freude, Karl Wilhelm Harde, Gustav Adolf Lohse (ed.): Die Käfer Mitteleuropas . tape 7 . Clavicornia. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Munich 1967, ISBN 3-8274-0681-1 . P. 280 Cisidae

- ↑ a b Nikolay B. Nikitsky, Dmitry S. Schigel: Beetles in polypores of the Moskow region in Entomologica Fennica. 29 April 2004 polyphagous in 20 species p. 14

- ^ Johannes Reibnitz, Roman Graf, Armin Coray: Directory of the Ciidae (Coleoptera) of Switzerland with information on nomenclature and ecology in communications from the Swiss Entomological Society 86: 63-88, 2013 p. 82 No. 40

- ↑ a b c Cristiano Lopez-Andrade, Fabiano Cumier-Costa, Carlos F. Sperber: Why do male Xylographus contractus Mellié (Coleoptera: Ciidae) present abdominal fovea? Evidence of sexual pheromone secretion in Neotrop. Entomol. vol 32 No. 2, Londrina, April / June 2003 doi : 10.1590 / S1519-566X2003000200005 , HTML

- ↑ T.-E. Fossli, J. Anderson: Host preference of Cisidae (Coleoptera) on tree-inhabiting fungi in Northern Norway Entomol Fennica. 9: 65-78. Abstract

- ^ A b Letícia V. Graf-Peters, Cristiano Lopes-Andrade, Rosa Mara B. da Silveira, Luciano de A. Moura, Mateus A. Reck, Flávia Nogueira de Sá: Host Fungi and Feeding Habits of Ciidae (Coleoptera) in a Subtropical Rainforest in Southern Brazil with an Overview of Host Fungi of Neotropical Ciids Florida Entomologist 94 (3): 553-566. 2011 at Bioone

- ↑ JKAckerman, RD Shenefelt: Organism, especially Insects, associated with wood rotting higher fungi (Basidiomycetes) in Wisconsin forests Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters Vol 61 p. 185 p. 203

-

^ A b c d e f

I. Hanski: Fungivori - Fungi, Insects and Ecology in Insect-Fungus interactions Editors: N. Wildling, NM Collins, PM Hammond, JF Webber, Academic Press 1989 ISBN 0-12-751800-2

Development polyresistance p. 40 f. in google book search; Development time of Hadraule blaisdelli p. 56; Early versus late settlers p. 42ff; Quantity hypothesis p. 34; in the case of early settlers, the structure of the fungi is decisive for the choice of host; Damage to the host primarily by early settlers p. 42 - ↑ Mats Jonsell, Clara Gonzáles Alonso, Mattias Forshage, Cees von Achterberg, Atte Comonen: Structure of insect community in the fungus Inonotus radiatus in riparian boreal forests Journal of Natural History 2016 doi: 10.1080 / 00222933.2016.1145273 p. 11

- ^ William G. Eberhard: The Funktion of Horns in Podischnus agenor (Dynastinae) and other beetles 15th International Congress of Entomology in Washington, DC, in 1976 in Morrey Blum: Sexual Selection and Reproductive Competition in Insects Elsevier 2012, p. 231 p. 243 ff ( Memento of the original from December 16, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ John F. Lawrence: Biology of the parthenogenetic Fungus beetle Cis fuscipes (Coleoptera: Ciidae) in Breviora - Museum of comparative Zoology Cambridge, Mass. Feb. 3, 1967 number 258 at BHL

- ↑ David Hagstum: Stored Product Insect Resource Elsevier, June 20, 2016 Sponge beetles as storage pests in the Google book search

- ↑ Cristiano Lopez-Andrade: The first record of Cis chinensis Lawrence from Brazil, with the delimitation of the Cis multidentatus species group (Coleoptera: Ciidae) Zootaxa 1755: 35 - 46 (2008) ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) in Tofu S. 42

- ↑ Distribution of Cisarthron laevicolle , distribution of Cisdygma clavicorne , distribution of Wagaicis wagae

- ↑ Glenda M. Orledge, Paul A. Smith, Stuart E. Reynolds: The non-pest Australian fungivor Cis bilamellatus Wood (Coleopter: Ciidae) in Northern Europe: spread dynamics, invasion success and ecological impact in Biological Invasion , Vol. 12, Issue 3, March 2010 doi: 10.1007 / s10530-009-9455-y

- ↑ Fauna Europaea, accessed on November 20, 2017 Family Ciidae

Web links

- Compilation of sources on beetle-fungus relationships: Dmitry S. Schigel: Fungivory and host associations of Coleoptera: a bibliography and review of research approaches . In: Mycology . Volume 3, 2012. pp. 258-272. doi : 10.1080 / 21501203.2012.741078 (currently unavailable)

- Gallery of the sponge beetles under construction