Siger of Brabant

Siger of Brabant (lat. Sigerus or Sigerius de Brabantia , * to 1235/1240 in Brabant , † before 10. November 1284 in Orvieto ) was philosophy teacher at the Paris arts faculty and representatives of radical Aristotelianism , which are closely aligned to Aristotle commentaries by Averroes oriented and therefore later, in connection with the term averroista ("Averroist") coined by Thomas Aquinas , was referred to as averroism .

To the biography

The person and the works of Siger had been forgotten for centuries and were only gradually rediscovered in the 19th century through the research initiated by Ernest Renan and Pierre Mandonnet . In the attribution, dating and interpretation of the traditional writings, in the assessment of their orthodoxy and, last but not least, in the question of how Thomas Aquinas and Dante Alighieri felt about Siger, the research has often been controversial and some things have remained in need of clarification.

Aristotelianism in Paris

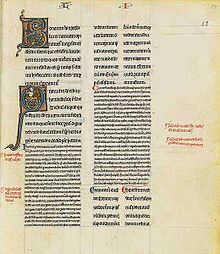

While the logical writings of Aristotle in the translation and commentary of Boethius together with his adaptation of the isagogue of Porphyrios belonged to the fixed curriculum of the Latin Artes since the early Middle Ages , the rest of the work of Aristotle - the writings of natural philosophy and the three books De anima , the metaphysics , the Nicomachean ethics and the Politics become known only since the 12th century through translations from Arabic and Greek, including transfers from Arab Aristotle comments, especially from Averroes and - Avicenna , as well as works of Maimonides and the pseudo-Aristotelian Liber de causis were added. The relationship between the knowledge of reason ( scientia ) and faith ( fides ), between philosophy and theology , thus found itself in a new tension. Up until then, the Augustinian conviction had been the guiding principle that although reason cannot fathom the ultimate mysteries of faith, it cannot come into irresolvable contradiction to it either, so that theology for its part can confidently make use of the means of reason of philosophy.

In the face of the new Aristotelian writings and their overriding systematics and argumentative stringency, this trust became fragile. In Paris there were repeated bans since 1210, which initially only concerned the reading and commentary on the natural philosophical writings, but then also included metaphysics . It was not until 1255 that the Parisian Artistic Faculty adopted the Aristotelian corpus in its teaching program without restriction, making it a compulsory program for all students. Since the study of Artes was a prerequisite for studying at the other three faculties, and therefore also compulsory for the theology students, suspicious resistance from the theological faculty was predetermined. It was mainly based on the Augustinian-oriented Franciscans , when their spokesman Bonaventure several times after 1267, not so much agitated against Aristotle himself, but against his contemporary declarer. Thomas Aquinas took a mediating position by advocating the scientific systematization of theology using the means of Aristotelian philosophy and trying to clear up any contradictions that occurred as a faulty application of the philosophical method. In the meantime, the teachers at the artist faculty, striving for an exact and philosophically stringent interpretation of the Aristotelian teaching system, came increasingly self-confidently to conclusions which were essentially already prepared by Averroes and which were in open contradiction to fundamental church doctrines.

The position of Siger

Siger von Brabant also appears as one of the exponents of this self-confident attitude, about whose origins and educational background nothing is known and who was first attested in 1266 as a master of the arts faculty and leader of one of the factions ( pars Sigerii ) in the dispute of nations at the University of Paris referred to in a later Inquisition document as canon of Saint Paul in Liège . Together with other faculty colleagues, of which particularly Boetius of Dacia has emerged yet by significant writings, he represented several of the most problematic for the Catholic Church doctrines, so especially the unity of a supra-individual, in all people that have an impact intellect with consequent mortality of the individual soul , the Eternity instead of the constitution of the world and the determination of nature and the impossibility of supernatural miracles . Although he presented such doctrines as rationally compelling conclusions of the via philosophica , he always kept himself covered by the declaration that he only had to use philosophical means and to interpret the intentions of Aristotle, but nevertheless to give priority to the contradicting revealed truths of faith in principle be.

The criticism of Thomas Aquinas

Through this development at the artist faculty, Thomas had to see his own concordance project endangered, as it emphasized the contradictions between Aristotelian doctrine and church doctrine, which he in turn endeavored to resolve. In addition, he had come to similar results at least in individual points and therefore had to fear that his mediating position could be equated with the more radical one if he did not make a clear distancing. In De unitate intellectus contra averroistas in 1270 he therefore strongly criticized the averroistic doctrine of the unity of the intellect, which his teacher Albertus Magnus had expressly distanced himself from as early as 1256, which was generally perceived as particularly scandalous . Thomas explicitly did not refer to the “documenta fidei” in his statement, thus avoiding playing off the revelation truth of the Bible against philosophy, but rather tried, within the framework of a demonstration limited to philosophical and philological arguments, to Averroes and his successors philosophical errors and a To prove distortion of the Aristotelian point of view. His argument was also not directed against Averroes in general, who was and remained one of the most important tools for Thomas and the whole of Scholasticism to access Aristotle, but his criticism was limited to the specific question of the unity of the intellect. Siger, who with his commentary on the third book of De anima is considered to be the actual addressee of the criticism in research, was not specifically addressed by Thomas, but it is referred to him when Thomas expresses the challenge in the final sentence that one contradicts his evidence, if at all, should be presented openly and in writing instead of in hidden corners ( in angulis ) or when teaching boys who are incapable of judgment.

The condemnation of 1270

However, this attempt at argumentative discipline has not yet been able to appease the conservative faction. Étienne Tempier , formerly a member of the theological faculty himself, chancellor of the university since 1263 and then bishop of Paris since 1268, issued a ban on 13 errors in December 1270, excommunicating all representatives of these errors, but without naming such representatives. Siger was able to relate the full catalog to his teachings without restriction, while Thomas could see himself particularly affected by Article No. 5, “that the world is eternal”, since he gave this question in De aeternitate mundi in the same year a clarification of his position had dedicated. The conviction had no immediate consequences for either of the two. Siger, who is said to have replied to Thomas in a paper De intellectu that has been lost today , also continued his lectures and continued to represent his views in a partly weakened form. Due to uncertainties in the dating and attribution of individual works, opinions in research differ as to how much Siger modified his positions and, as a result, came closer to Thomism. In 1272 there was another disciplinary measure when the artist faculty forbade all teaching members, under threat of expulsion, from dealing with purely theological topics such as the Trinity or with questions concerning philosophy and faith in the matter of contra fidem (against faith) to judge, whereby in the latter case in addition to the exclusion, the charge of heresy was threatened. Under these conditions, free philosophizing evidently had to assume a clandestine character, because in 1276 the faculty prohibited teaching in secret or private circles.

The condemnation of 1277

In letters of January 18 and April 28, 1277 Pope John XXI. Inquiries from Bishop Tempier about heretical activities that have become known because of rumors "of some students of both Artes and the theological faculty" ( nonnulli tam in artibus quam in theologica facultate studentes Parisius ). Caused by the first of these two letters or on the basis of an investigation that had been prepared for some time, Tempier condemned a catalog of 219 errors on March 7, 1277. The condemnation was directed expressly against members of the artist faculty as propagators of the errors, but without naming them again this time. Nonetheless, contemporaries referred it particularly to Siger and Boetius von Dacien. Also positions of Thomas Aquinas - the three years was previously deceased - were also affected by this conviction, so that in 1325 several of his doctrine to-live errores in terms of its now done canonization (1323) again officially by a successor Tempiers from this list removed.

Perhaps the most serious accusation, which has at least preoccupied research, is already formulated in the preamble to the condemnation, namely the accusation of spreading the doctrine of "two, as it were, opposing truths" ( quasi sint duae contrariae veritates ), according to which there is a truth secundum philosophiam and another truth secundum fidem catholicam give. In this clear form, the accusation is not covered by the surviving writings of Siger or other contemporaries. Wherever Siger refers to contradictions in his statements about fides , he always attaches importance to the fact that his statements can be proven in a philosophical sense, but only to designate the contradicting doctrine of faith as veritas and to expressly give it priority.

The end of Siger

At the time of the conviction in 1277, Siger had already left Paris and evidently retired to Liege, from where he and two other former members of the Paris Artistic Faculty were summoned to the Inquisitor of France Simon du Val on November 23, 1276 . It is unknown whether Siger faced the court. However, the few remaining evidence, which are not entirely indubitable in their testimony value, suggest that he went to Orvieto to justify himself to the papal curia and that he died there sometime before November 1284. A letter dated November 10, 1284 from the Franciscan and Archbishop Johannes Peckham , who had been rector of the University of Paris from 1269–1271 and a committed representative of the conservative faction and now noted with satisfaction in his letter about Siger and Boetius von Dacien that the two were in Italy would have come to a miserable end. One of the extensions to Martin von Troppau's chronicle states that soon after arriving at the Curia, Siger was stabbed to death by his own secretary in a fit of madness ( ibique post parvum tempus a clerico suo quasi dementi perfossus periit ), in which case his death would be expected in the late 1970s rather than the early 1980s. In the Italian poem Il Fiore , the author of which Durante is sometimes identified with Dante Alighieri , Falsembiante, the personification of hypocrisy, prides himself on having put a painful end to Siger at the Curia in Orvieto with the “sword” ( Mastro Sighier non andò guari lieto : / A ghiado il fe 'morire a gran dolore / Nella corte di Roma, ad Orbivieto [Fiore 92,9–11]), which suggests the otherwise unlikely thought of an execution, but also less specifically a violent death accompanied by insidiousness could rewrite and then still be roughly compatible with the other two certificates.

Siger in Dante's Paradiso

Since Siger's historical rediscovery, the interest in the question of his orthodoxy and his relationship to Thomas has been largely due to questions raised by Siger's depiction in Dante's Commedia . Siger appears there in one of the two groups of twelve representatives of wisdom, whose light souls float in the solar sky of Paradiso in concentric circles above the heads of the afterlife visitor Dante and his guide Beatrice, and of which the first group passes through Thomas Aquinas and the second through Bonaventure is cited. Thomas, who introduced the members of his circle one after the other - namely his teacher Albertus Magnus , the canon law teacher Gratian , the theologian Petrus Lombardus , King Solomon , Dionysius Areopagita , then a person who was not clearly identified, who was either the church father Ambrose or the Historian Orosius acts, Boëthius and finally Isidore of Seville , Beda Venerabilis and Richard of St. Viktor -, then also presents Siger as the last (Par. 10.133-138):

- Questi onde a me ritorna il tuo riguardo,

- è 'lume d'uno spirto che' n pensieri

- gravi a morir li parve venir tardo:

- essa è la luce etterna di Sigieri,

- che, leggendo nel Vico de li Strami,

- silogizzò invidiosi veri.

- This one from whom your gaze returns to me

- is the glow of a mind that is in its serious thoughts

- didn't seem to go fast enough with dying:

- this is the eternal light of Siger,

- who, at his lectures in the Rue du Fouarre (the seat of the artist faculty),

- came to envious truths through syllogisms .

Similar to the second group, where Bonaventure was the last to introduce Joachim von Fiore , a wisdom teacher whose teaching had been condemned several times by the church, in the case of Sigers, too, since the rediscovery of his works and historical biographical dates, Dante research was faced with the question of why Dante of all people included this philosopher, who was precarious in his orthodoxy, into the circle of these twelve and then placed him at the side of his former adversary Thomas. This has been interpreted partly as Dante's avowal of Averroism or at least to philosophize free from the constraints of church dogmatics , partly also as a reference to a late conversion of Siger to Thomism, if it was not assumed that Dante only knew Siger as an important teacher of the Parisian artist faculty, but had no knowledge of the controversies about his teaching.

Dante's choice of Siger (and also Joachim) appears all the more mysterious when one takes into account that, through their number, arrangement and other characteristics, he put his two groups of wisdom teachers in a relationship with the most important wisdom teachers of mankind in the Christian understanding, the twelve Apostles of Christ, and to other biblical and cosmic groups of twelve that were traditionally assigned to the apostles of Christ . In the apostles' catalogs of the Gospels , the traitor Judas appears in the position of twelfth (after his death, he is replaced by Matthias by drawing lots). Judas has traditionally been interpreted as the figure of all traitors, false teachers and apostates of the Christian faith. It can certainly be ruled out that Dante Siger (and Joachim) would have judged Siger (and Joachim) in this sense as a typical Judaism, since otherwise he would have depicted him among the heretics in the Inferno . But Siger's final position in his group of twelve and the repetition of this allusion principle with Joachim in the second group at least make it clear that the problematic orthodoxy of Siger Dante was just as little unknown as that of Joachim, but is rather consciously reflected on by him.

The concrete biographical reference of Dante's statement about what appears to be Siger's longing for death is unknown, and the exact meaning of his formulation invidiosi veri is not entirely clear, but can best be understood in the sense of Fiore in such a way that Siger through his teaching Had aroused envy and resentment. The fact that Dante knew Siger specifically as a representative of the doctrine of the unity of the intellect is possibly indicated by the designation of his light soul as luce etterna di Sigieri and then to be understood as an ironic indication that Siger in the hereafter is precisely that "eternity" and immortality of the individual soul personally experience and enjoy, which he thought he had to deny her during his lifetime in the context of his presentations on the unity of the intellect. So if there is some evidence that Dante had a very clear idea of the person and teaching of Siger and still did not share this teaching, but actually refuted it through the act of grace of a transfer to paradise, then the riddle of his salvation into eternal life actually arises only one obvious solution, namely that Dante Siger was specifically not one of the damned because, even in his exclusively rational philosophizing, he neither despaired of his knowledge nor fell away from faith, but kept the conviction that in doubt, faith and not to be faithful to human reason, as he once said in his work De anima intellectiva (Chapter VII):

- Mihi dubium fuit a longo tempore, quid vi naturalis rationis praedicto problemate sit tenendum, et quid senserit Philosophus de dicta quaestione, et ideo in tali dubio fidei adherendum est, quae omnem rationem humanam superat.

- For a long time I was in doubt as to what to think of the problem mentioned by virtue of natural reason, and what the philosopher (Aristotle) thought on this question, and therefore, in such a doubt, one should cling to a belief that transcends all human reason.

See also

Work editions

Latin editions:

- Matthias Perkams: Siger von Brabant, Quaestiones in tertium De anima: Latin / German, along with two averroistic answers to Thomas Aquinas - On the doctrine of the intellect according to Aristotle. Edited, translated, introduced and annotated. Herder Verlag, Freiburg i.Br. [u. a.] 2007 (= Herder's Library of Philosophy of the Middle Ages Volume 12), ISBN 978-3-451-29033-6

- Bernardo Bazán: Siger de Brabant, Quaestiones in tertium de anima, De anima intellectiva, De aeternitate mundi . Publications Universitaires, Louvain; Éditions Béatrice-Nauwelaerts, Paris 1972 (= Philosophes médiévaux, 13)

- Cornelio Andrea Graiff: Siger de Brabant, Questions sur la Métaphysique. Texts inédit. Éditions de l'Institut Supérieur de Philosophie, Louvain 1948 (= Philosophes médiévaux, 1)

- William Dunphy, Armand Maurer: Siger de Brabant, Quaestiones in metaphysicam. Éditions de l'Institut Supérieur de Philosophie, Louvain-la-Neuve 1981–1983 (= Philosophes médiévaux, 24–25), vol. I, William Dunphy: Edition revue de la reportation de Munich. Texts inédit de la reportation de Vienne (1981); vol. II, Armand Maurer: Texts inédit de la reportation de Cambridge. Edition revue de la reportation de Paris (1983)

- Géza Sajò: Un traité récemment découvert de Boèce de Dacie, De mundi aeternitate, texte inédit avec une introduction critique. Avec en appendice un texte inédit de Siger de Brabant Super VI metaphysicae. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1954

- Bernardo Bazán: Siger de Brabant, Écrits de logique, de morale et de physique, edidition critique. Publications Universitaires, Louvain; Éditions Béatrice-Nauwelaerts, Paris 1974 (= Philosophes médiévaux, 14), contains: Sophisma Omnis homo de necessitate est animal, pp. 43–52; Quaestio utrum haec sit vera: homo est animal, nullo homine existente, pp. 53-59; Quaestiones logicales, pp. 60-66; Impossibilia, pp. 67-97; Quaestiones morales, pp. 98-105; Quaestiones naturales (Lisbon), pp. 106-113; Quaestiones naturales (Paris), pp. 114-126; Compendium super De generatione et corruptione, pp. 127-140; Quaestiones in Physicam (ed. Albert Zimmermann), pp. 149-184

- JJ Duin: La doctrine de la providence dans les écrits de Siger de Brabant: textes et étude. Publications Universitaires, Louvain; Éditions Béatrice-Nauwelaerts, Paris 1954 (= Philosophes médiévaux, 3), pp. 14–50: De necessitate et contingentia causarum.

- Antonio Marlasca: Les Quaestiones super librum de causis de Siger de Brabant: édition critique , Publications Universitaires, Louvain; Éditions Béatrice-Nauwelaerts, Paris 1972 (= Philosophes médiévaux, 12)

- Dragos Calma / Emanuele Coccia: Un commentaire inédit de Siger de Brabant sur la Physique d'Aristote (ms. Paris, BnF, lat. 16297). In: Archives d'histoire doctrinale et littéraire du Moyen Âge 73.1 (2006), pp. 283-349

Translations:

- Matthias Perkams: Quaestiones in tertium De anima (see Latin editions)

- Wolf-Ulrich Klünker, Bruno Sandkühler: Human soul and cosmic spirit: Siger von Brabant in the dispute with Thomas von Aquin, with a translation of Sigers De anima intellectiva (About the spirit soul). Verlag Freie Geistesleben, Stuttgart 1988 (= contributions to the history of consciousness, 3), pp. 39–77 [German translation and interpretation from an anthroposophical perspective]

- Cyril Vollert, Lottie H. Kendzierski, Paul M. Byrne: On the Eternity of the World (De Aeternitate Mundi). St. Thomas Aquinas, Siger of Brabant, St. Bonaventure. Translated from the Latin, with introductions. Marquette University, Milwaukee (WI) 1984, ISBN 0-87462-216-6 , pp. 84-95

Electronic texts:

- Siger: Quaestiones in tertium de anima (lat.)

- Siger: Questions on Book III of the De anima (English translation by Robert Pasnau; PDF; 331 kB)

- Siger: Quaestiones in tertium de anima, qu. IX: Utrum sit unus intellectus in omnibus (lat.)

- Siger: De anima intellectiva, cap. VII: Utrum anima intellectiva multiplicetur multiplicatione corporum humanorum (lat.)

- Siger: On the intellectual soul, chap. VII: Whether the intellective soul is multiplied in accord with the multiplication of human bodies (by JA Arnold and JF Wippel)

- Siger: De aeternitate mundi (lat.)

- Siger: Questions sur la Métaphysique, Reportation de Vienne, Livre VI, Commentaire 1 (French translation by Fabienne Pironet)

- Thomas Aquinas: De unitate intellectus contra Averroistas (lat.)

- Étienne Tempier: Catalog of the 219 condemned doctrines from 1277 (lat.)

literature

- Emanuele Coccia: La trasparenza delle immagini. Averroè è l'averroismo. Bruno Mondadori, Milan 2004, ISBN 88-424-9272-8

- Antonio Petagine: Aristotelismo difficile: l'intelletto umano nella prospettiva di Alberto Magno, Tommaso d'Aquino e Sigieri di Brabante. Vita e Pensiero, Milan 2004, ISBN 88-343-5023-5

- Luca Bianchi: Censure et liberté intellectuelle à l'Université de Paris. Les Belles Lettres, Paris 1999 (= L'âne d'or, 9), ISBN 2-251-42009-6

- David Piché: La condamnation parisienne de 1277, nouvelle édition du texte latin, traduction, introduction et commentaire, avec la collaboration de Claude Lafleur. Vrin, Paris 1999, ISBN 2-7116-1416-6

- Tony Dodd: The life and thought of Siger of Brabant, thirteenth-century Parisian philosopher: an examination of his views on the relationship of philosophy and theology. E. Mellen Press, Lewiston 1998, ISBN 0-7734-8477-9

- Ruedi Imbach , François-Xavier Putallaz: Profession philosophy: Siger de Brabant. Éditions du Cerf, Paris 1997, ISBN 2-204-05696-0

- Kurt Flasch : Enlightenment in the Middle Ages? The condemnation of 1277. The document of the Bishop of Paris introduced, translated and explained , Dieterich Verlag, Mainz 1989 (= Excerpta classica, 6), ISBN 3-87162-016-5 , 3871620173

- René Antoine Gauthier : Notes sur Siger de Brabant, I: Siger en 1265 . In: Revue des sciences philosophiques et théologiques 67 (1983), pp. 201-232; II: Siger en 1272-1275, Aubry de Reims et la scission des Normands , ibd. 68 (1984), pp. 3-49

- Edouard Henri Wéber: La controverse de 1270 à l'Université de Paris et son retentissement sur la pensée de S. Thomas d'Aquin. Vrin, Paris 1970 (= Bibliothèque thomiste, 40)

- Fernand Van Steenberghen : Maître Siger de Brabant. Publications Universitaires, Louvain; Vander-Oyez, Paris; 1977 (= Philosophes médiévaux, 21), ISBN 2-8017-0063-0

- Johannes J. Duin: La doctrine de la providence dans les écrits de Siger de Brabant: textes et étude. Institut Supérieur de Philosophie, Louvain 1954 (= Philosophes médiévaux, 3)

- Pierre Mandonnet : Siger de Brabant et l'averroïsme latin au XIIIme siècle: étude critique et documents inédits . Librairie de l'Université, Friborg (Switzerland) 1899; 2me éd. review and augmentée: Siger de Brabant et l'averroïsme latin au XIIIme siècle , 1st étude critique , Institut Supérieur de Philosophie de l'Université, Louvain 1911; 2. Textes inédits , ibid. 1908

- Ernest Renan : Averroès et l'averroïsme: essay historique. Auguste Durand, Paris 1852; 3me édition revue et augmentée, Levy, Paris 1866; Reprint of the 3rd edition: Institute for the History of Arab-Islamic Sciences at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University, Frankfurt 1985 (= publications of the Institute for the History of Arabic-Islamic Sciences, B.1); Another new edition with a French foreword by Alain de Libera: Maisonneuve & Larose, Paris 1997, ISBN 2-7068-1289-3

- Klaus Kienzler : Siger von Brabant. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 10, Bautz, Herzberg 1995, ISBN 3-88309-062-X , Sp. 257-260.

To Siger and Dante:

- Otfried Lieberknecht: Allegory and Philology: Reflections on the problem of the multiple sense of writing in Dante's «Commedia». Steiner, Stuttgart 1999 (= text and context, 14), ISBN 3-515-07326-4 , chap. 3: Biblical subtext and allegorical sense: Paradiso 10/12 ( PDF, 2,415 kB )

- Louis Marcello La Favia: Thomas Aquinas and Siger of Brabant in Dante's "Paradiso" . In: Paolo Cherchi, Antonio C. Mastrobuono: Lectura Dantis Newberryana: Lectures presented at The Newberry Library Chicago, Illinois 1985–1987 , vol. II, Northwestern University Press, Evanston (Ill.) 1990, pp. 147-172

- Albert Zimmermann : Dante was right. New results of research on Siger von Brabant. In: Philosophisches Jahrbuch der Görres Gesellschaft 75.1 (1967/68), pp. 206-217

- Martin Grabmann: Siger von Brabant and Dante. In: Deutsches Dante-Jahrbuch 21 (1939), pp. 109–130

Web links

- Literature by and about Siger von Brabant in the catalog of the German National Library

- Alexander Baumgarten: Miracle and Discourse: The Rise of the Theory of Science in Latin Averroism and the Problem of the Double Truth

- Alexander Baumgarten: Disputation on the Unity of the Intellect and the Birth of Parisian University Intellectual (PDF file; 1.47 MB)

- Antoine Côté: Siger and the Skeptic (PDF file; 167 kB)

- Maurice De Wulf: History of Medieval Philosophy , 3rd ed. (1909), Chap. IV, 1: Latin Averroism

- FJ Fortuny: La física de Aristóteles y las' físicas'aristotélicas medievales: Tomás de Aquino y Siger de Brabant sobre el Liber de Causis (III)

- Peter Grabher: The Paris Condemnation of 1277: Context and Significance of the Conflict over Radical Aristotelianism. Master's thesis, University of Vienna 2005 (PDF file; 3.1 MB)

- Martin Grabmann: Latin averroism . In: Annual Reports for German History 5 (1929/1931), pp. 407–408

- Gyula Klima: Natural Necessity and Eucharistic Theology in the late 13th century, 6: Siger of Brabant's Position

- Gianluca Miligi: Sulla "domanda metafisica": Gli "Invidïosi veri" di Sigieri di Brabante (PDF file; 108 kB)

- Ignacio Pérez Constanzó: La función de la filosofía y la doble verdad en Siger de Brabante

- Fabienne Pironet: Siger de Brabant

- Fabienne Pironet: Bibliography on Siger de Brabant (PDF file; 124 kB)

- Hans Thijssen: Condemnation of 1277. In: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Siger of Brabant |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Sigerus de Brabantia; Brabant, Siger de; Siger de Brabant; Sugerus de Brabantia; Sigieri di Brabante; Sigerus Brabantinus; Segerus de Brabantia |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1235 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Brabant |

| DATE OF DEATH | before November 10, 1284 |

| Place of death | Orvieto |