Small fort Tisavar

| Small fort Tisavar | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Tisavar |

| limes |

Limes Tripolitanus front Limes line |

| section | Eastern Sand Sea |

| Dating (occupancy) | around 184/191 AD up to a maximum of Maximinus Daia (305-313) |

| Type | Small fort |

| unit | Vexillation of the Legio III Augusta |

| size | 28 × 37.50 m (= 0.1 ha) |

| Construction | stone |

| State of preservation | exceptionally well-preserved rectangular complex |

| place | Ksar Rhilane / Ksar Ghilane / Ksar Ghelane |

| Geographical location | 33 ° 0 ′ 31 " N , 9 ° 36 ′ 58.4" E |

| height | 221 m |

| Previous | Bir Mahalla small fort (east) |

| Subsequently | Centenarium Tibubuci (northeast) |

The small fort Tisavar is a Roman military camp , the crew of which was responsible for security and surveillance tasks on the Limes Tripolitanus in the province of Africa proconsularis . The border fortifications formed a deep system of forts and military posts. The small plant is now located near the desert oasis Ksar Ghilane / Ksar Rhilane, around 75 kilometers west of the city of Tataouine , Kebili Governorate , southern Tunisia .

location

The mounting is located on an isolated hill, bel above the Wadi Recheb the northern edge of the Sahara belonging East Grand sand sea . For a long time the place could only be reached by camels and vehicles suitable for the desert. Today a continuously paved road leads from Douz or Matmata to the oasis of Ksar Ghilane / Ksar Rhilane (formerly also called Henchir el-Hagueuff), which is around three kilometers south of the fort. The desert town owes its present existence to an artesian thermal spring , which opened up after the Second World War during a failed oil well. As a result, date palms were planted. In addition to the date harvest, the nomads living there today keep goats and sheep . The fort itself was built on a ledge and thus on solid ground. From the somewhat elevated location, the crew had a wide all-round view, with the first dunes of the hostile Eastern Sand Sea appearing immediately to the south. With this military outpost, the Roman army had pushed the frontier to the edge of the Sahara.

Research history

The structural remains of the fort have survived the passage of time in very good condition since ancient times. After the conquest of the last Eastern Roman Tripolitania by the advancing Islamic armies and the subsequent linguistic and cultural assimilation , the place was given the Arabic nickname “ Ksar ”, a word that stood for “military camp” during the early medieval Islamic expansion phase . In the 16th century, a local Berber tribe temporarily occupied the castle ruins.

In 1885 the facility was discovered by the French battalion commander, Captain Marie Georges Henri Lachouque (1846–1928), a member of a cartographic department. The damaged building inscription of the small fort was discovered back then and first described and supplemented in 1887 by the archaeologist René du Coudray de La Blanchère (1853-1896). With reference to Lachouque, De La Blanchère also mentioned the location and time of the complex. Just one year later, in 1888, the archeology pioneer Charles-Joseph Tissot (1828–1884) presented his interpretation of the fortification and also referred to the Lachouque Breach. In 1892, the historian and epigrapher René Cagnat (1852-1937) published for the first time the still very simple floor plan of the fort with the adjoining outbuilding, as recorded by Lachouque, as well as two sketches of the two visible ruins.

But it was not until 1900 that Lieutenant Georges Louis Gombeaud (1870–1963) exposed the remains of the wall from the sand and published his research results in 1901. The officers were among the military personnel that the archaeologist Paul Gauckler (1866–1911) during his two-year research campaigns on Limes Tripolitanus had been made available. During the excavations in 1900, a fragment of a terracotta lamp with a portrait of the Egyptian - Hellenistic god Serapis-Helios was found . The historical reports and research at the small fort differ from one another in terms of details, as well as some dimensions and interpretation.

During the Second World War , the battle of Ksar Ghilane took place here on March 10, 1943 .

The Franco-Tunisian joint project carried out from 1968 to 1970 to research the southern Tunisian section of the mid-imperial Limes Tripolitanus brought the garrison site back into the light of science, but the ancient historian Maurice Euzennat (1926-2004) and the archaeologist Pol Trousset left it with the historical plan . Modern topographical surveys and a systematic field inspection were apparently not carried out at that time and have not been made up to this day. In addition, unspecified repair and restoration measures have contributed to some blurring of the ancient building stock.

In February 2012, the Tunisian government submitted an application on behalf of the responsible governorates to declare the small fort Tisavar as part of the Roman Limes in southern Tunisia a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Building history

Enclosing wall

In October 2008, the archaeologist Michael Mackensen re- measured the usable inner surface of the small fort for the first time since the early excavations. A covered area of 25.40 × 34.80 meters (= 0.08 hectares) was found. In Lachouque, the outside diameter is still 25 × 30 meters. These data were taken over by the early research by Tissot, Cagnat and the artillery lieutenant Henri Lecoy de La Marche , while shortly afterwards Gauckler also stated an outer diameter of 30 × 40 meters from Gombeaud's excavations. This dimension was adopted from most of the later publications. Using his new measurements, Mackensen calculated external dimensions of 28 × 37.50 meters, which corresponds to a built-up area of 0.1 hectare.

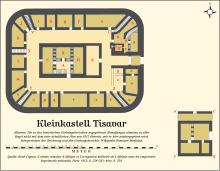

In accordance with its scale and capacity, the building scheme for Roman garrisons, which was unified during the Principate , was developed. In addition to the rectangular floor plan with rounded corners (playing card shape), each with a tower, which was typical of mid-imperial fortifications, the rectangular crew quarters and the necessary infrastructure - storage rooms and a water reservoir (room "R" in the plan drawing) - were all around in 20 chambers an inner courtyard and leaned with their back directly against the 1.20 to 1.40 meters thick and originally around four meters high surrounding wall, which had a poorly preserved crenellated wreath from the early excavations. Before the construction of the facility, the Roman surveyors had aligned the future long side of the fortification, which is located on a 40 × 40 meter high hill, almost exactly on an imaginary west-east axis. The only single-lane gate was built in the middle of the narrow eastern side of the fence. It was measured by Gombeaud to be three meters high.

The vaulted archway that has been preserved on the narrow eastern side of the fort consists of large, unprofiled limestone blocks that have been adapted to the arch shape and cut into a wedge shape. The arch measures a crown height of three meters and has a clear width of 2.25 meters. There were no further entrances to the interior of the facility. With the exception of the essential load-bearing and supporting structural elements, which also mostly consist of large blocks, the walls are usually made of roughly cut hand blocks and rubble stones. A mighty, rectangular stone block has been preserved above an access inside, which is still used as a lintel today. The inscription Iov (i) Opt (imo) Max (imo) Vic (tori) (" Jupiter , the best, greatest, the victor") is carved on it. The battlements around the surrounding wall could be accessed by stairs in the four corners as well as on the east and west sides. Mackensen assumed that Tisavar had no corner or intermediate towers.

Interior development

To get into the interior from the driveway, the soldiers first had to cross a seven-meter-long corridor that was formed by two outer walls of the crew quarters. Since most of the remains of the wall are still taller than a man, many structural details can be studied that are no longer traceable in this form in other Tunisian small fortifications. The large inner courtyard of the facility is taken up by a rectangular staff building (Principia) measuring 12.60 × 7.40 meters . Like the headquarters of large forts, this building had a small inner courtyard, which is marked as "A" in the plan. A staircase shows that the building had at least one first floor. The center of the small fort was formed by a shrine to Jupiter, which forms a unit with the staff building and adjoins it in the east as room "E". There was an inscription dedicated to Jupiter and Victoria, the goddess of victory, above the entrance to this sanctuary, which was also to the east. Obviously this cult area had no roof and the walls were a maximum of 1.60 meters high. Inside the sanctuary there were niches, in one of which, completely buried by the sand, an altar was found that was dedicated to the genius loci of Tisavar. The excavators collected the remains of eight other altars, which were similar, or at least approximately similar, to the former. The commander's living quarters, which would have had no space in the small principia , are searched for in a room wing attached to the defensive wall. The room designated as “R” in the plan for the fort was a cistern that, according to the excavators, held “a little more than 2,000 liters” of water.

Surrounding development

Around ten meters, to Lachouque 15 meters, east of the fortification, there was a small foundation of around nine square meters, which could possibly have been a stable. Other structural remains were a little further to the east. There were several rooms built next to each other with a variable length of 1.30 to 1.90 meters. The relatively roughly built rooms had no connection to each other and all opened up to the fort. The excavators wondered whether these rooms could possibly have served as a sheepfold, as a stable in general, or as an advanced line of defense.

Building inscription

Tisavar, whose ancient name has been preserved on two inscriptions found at the fort, was built between AD 184 and 191 during the reign of Emperor Commodus (180-192) , according to the building inscription that was also found :

[Imp (eratori) Cae] s (ari) M (arco) A [u] r (elio) Commodo

[Antoni] no Pio Fel (ici) Aug (usto) Germa-

[nic (o) Sar] mat (ico) Britan (nico) maximo

[---] l [eg (ato)] Aug (usti) pr (o) [pr] aet (ore)

[---] sub cura Claudi (a?) N [i --- ]

[procura] t (oris) Aug (usti) r [eg (ionis) The] ve-

[stinae

Translation: “For Emperor Marcus Aurelius Commodus Antoninus, the pious, happy, sublime, the greatest victor over Germania, Sarmatia, Britain, [...] governor [–––] under the supervision of Claudi (a) nus, procurator of the thevestine region. "

In addition to the inscription reproduced below, the ancient place name, which is not mentioned in the Itinerarium Antonini or in the Tabula Peutingeriana , was preserved on plastered walls by means of a brush inscription:

[---] Tisavar

[---] ta

[---] cen

[---]

Troop

The crew consisted of a vexillation of the Legio III Augusta , which was stationed in the Lambaesis camp . The dedicatory inscription from another Jupiter shrine outside the small fort reveals not only the place name but also the names of the officers active at the time:

- Genio Ti

- savar Aug (usto) s (acrum)

- Ulpius Pau-

- linus | (centurio) [[leg (ionis)]]

- [[III Aug (ustae)]] v (otum) s (olvit) cum

- vex (illatione) cui praef (uit)

- Vibiano and Myrone

- opt (ionibus)

Translation: “Dedicated to the genius Tisavar Augustus. Ulpius Paulinus, centurion of the Legio III Augusta has redeemed his vows together with the vexillation, which he presided over, with the NCOs ( Optiones ) Vibianus and Myron. "

Historical outline and dating

After the occupation of Numidia in the 1st century AD, the Roman army began to advance into Tripolitania. In the early 2nd century AD, the construction of roads, forts and barriers was intensified here. The region around the salt lakes in the south of what is now Tunisia was connected to the outer south by a road. The starting point was the Telmine oasis, where Roman inscriptions from this period were also found. Their end point was at today's Remada. From here two further strands branched off into the mountainous regions (Djebel) of Triplitania and south to the oasis of Ghadames, in the west of the desert region Hamadah el Hamra. Tisavar , built in the late 2nd century AD, was one of the forts furthest to the west of the building program begun during the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117-138) . During this phase, other fortifications were built, such as the Bezereos or Tillibari (Remada) castles . According to some scholars, Tisavar was possibly given up again during the reign of Emperor Diocletian (284-305) in favor of the northeastern small fort , inscribed as Centenarium Tibubuci (Ksar Tarcine). On the other hand, a final coin from the small fort, minted during the reign of Emperor Maximinus Daia (305-313) , points to a somewhat later end. Inside the Tisavar complex and in the surrounding buildings, a continuous horizon of destruction by fire and the associated reddening of the walls were found. This fire marks the end of the development of the garrison site.

Lost property

Roman finds from the excavation at the fort are now in the National Museum of Bardo , Tunis .

literature

- Michael Mackensen : The small fort Tisavar / Ksar Rhilane at the time of the commodity period on the southern Tunisian "limes Tripolitanus". In: Kölner Jahrbuch. 43 (2010), pp. 451-468.

- Erwin M. Ruprechtsberger : The Roman Limes Zone in Tripolitania and the Cyrenaica, Tunisia - Libya (= writings of the Limes Museum Aalen. No. 47). Society for Prehistory and Early History in Württemberg and Hohenzollern, Stuttgart 1993.

- René Cagnat : La frontière militaire de la Tripolitaine X l'époque romaine . In: Mémoires de l'Institut national de France. Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres , Volume 39, Paris 1914, pp. 77-109; here: pp. 101-103.

- René Cagnat: L'armée romaine d'Afrique et l'occupation militaire de l'Afrique sous les empereurs . 2nd edition, Imprimerie nationale, Leroux, Paris 1912; Pp. 558-561.

- René Cagnat: L'armée romaine d'Afrique et l'occupation militaire de l'Afrique sous les empereurs . Imprimerie nationale, Léroux, Paris 1892.

- Adolf Schulten : Archaeological news from North Africa . In: Archäologischer Anzeiger. Supplement to the yearbook of the Archaeological Institute. (1904), pp. 117-139; here: p. 132.

- Georges Louis Gombeaud : Fouilles du castellum d'El-Hagueuff (Tunisie). In: Bulletin archéologique du comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques. 1901, pp. 81–94 ( digitized version )

- Charles-Joseph Tissot : Géographie comparée de la province romaine d'Afrique 2, Paris 1888, p. 706 f.

- René du Coudray de La Blanchère : Découvertes archéologiques en Tunisie . In: Bulletin archéologique du comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques. 1887, p. 438 f.

Web links

- The fort as part of a research project of the Institute for Prehistoric and Protohistoric Archeology and Provincial Roman Archeology of the LMU Munich ( Memento from May 30, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), wayback, accessed on February 5, 2016.

- Picking up the gate

Remarks

- ↑ a b c d e Michael Mackensen : The small fort Tisavar / Ksar Rhilane from the Commodus period on the southern Tunisian "limes Tripolitanus". In: Kölner Jahrbuch. 43 (2010), pp. 451-468; here: p. 455.

- ↑ Michael Mackensen : forts and military posts of the late 2nd and 3rd centuries on the "Limes Tripolitanus" . In: Der Limes 2 (2010), pp. 20–24; here: p. 22.

- ↑ Michael Mackensen : The small fort Tisavar / Ksar Rhilane at the time of the commodity period on the southern Tunisian "limes Tripolitanus". In: Kölner Jahrbuch. 43 (2010), pp. 451-468; here: p. 451.

- ↑ Wadi bel Recheb at 33 ° 4 '32.79 " N , 9 ° 49' 7.52" O , 32 ° 55 '20.15 " N , 9 ° 35' 16.2" O

- ^ A b Michael Mackensen, Hans Roland Baldus : Military camp or marble workshops. New investigations in the eastern area of the Simitthus / Chemtou labor and quarry camp. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2005, ISBN 3-8053-3461-3 , p. 70.

- ↑ a b Pol Trousset: Recherches sur le limes tripolitanus. Center national de la recherche scientifique, Paris 1974, ISBN 2222015898 , p. 93.

- ^ René du Coudray de La Blanchère: Découvertes archéologiques en Tunisie . In: Bulletin archéologique du comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques. 1887, p. 438 f.

- ^ Charles-Joseph Tissot : Géographie comparée de la province romaine d'Afrique 2, Paris 1888, p. 706 f.

- ↑ a b c René Cagnat: L'armée romaine d'Afrique et l'occupation militaire de l'Afrique sous les empereurs . Imprimerie nationale, Léroux, Paris 1892, p. 560 f. with illustrations.

- ^ Paul Gauckler: Le Centenarius de Tibubuci (Ksar-Tarcine, South Tunisia). In: Comptes-rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 1902, pp. 321-340; here pp. 321–323.

- ↑ Laurent Bricault (Ed.): Isis en occident. Actes du IIème Colloque international sur les études isiaques, Lyon III 16-17 May 2002. Brill, Leiden 2004, ISBN 9789004132634 , p. 238.

- ↑ a b Michael Mackensen : The small fort Tisavar / Ksar Rhilane at the time of the Commodus on the southern Tunisian "limes Tripolitanus". In: Kölner Jahrbuch. 43 (2010), pp. 451-468; here: p. 454.

- ↑ Michael Mackensen : The small fort Tisavar / Ksar Rhilane at the time of the commodity period on the southern Tunisian "limes Tripolitanus". In: Kölner Jahrbuch. 43 (2010), pp. 451-468; here: p. 454.

- ↑ UNESCO: Border systems of the Roman Limes: The Limes in Southern Tunisia [1] , accessed on January 18, 2019.

- ↑ a b c Michael Mackensen : The small fort Tisavar / Ksar Rhilane from the Commodus period on the southern Tunisian "limes Tripolitanus". In: Kölner Jahrbuch. 43 (2010), pp. 451-468; here: p. 456.

- ^ Michael Mackensen, Hans Roland Baldus: Military camp or marble workshops. New investigations in the eastern area of the Simitthus / Chemtou labor and quarry camp. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2005, ISBN 3-8053-3461-3 , p. 72.

- ^ René Cagnat: L'armée romaine d'Afrique et l'occupation militaire de l'Afrique sous les empereurs . Imprimerie nationale, Paris 1912; Pp. 558-561; here: p. 558.

- ↑ CIL 8, 22760 .

- ↑ Michael Mackensen: Crew accommodation and organization of a Severan legion vexillation in the Tripolitan fort Gholaia / Bu Njem (Libya). In: Germania. 86/1 (2008), pp. 271-307; here p. 278.

- ^ Michael Mackensen, Hans Roland Baldus: Military camp or marble workshops. New investigations in the eastern area of the Simitthus / Chemtou labor and quarry camp. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2005, ISBN 3-8053-3461-3 , p. 71; Fig. Of the floor plan.

- ^ A dedicatory inscription: CIL 8, 22759 .

- ^ A b René Cagnat: L'armée romaine d'Afrique et l'occupation militaire de l'Afrique sous les empereurs . Imprimerie nationale, Paris 1912; Pp. 558-561; here: p. 561.

- ^ Michael Mackensen, Hans Roland Baldus: Military camp or marble workshops. New investigations in the eastern area of the Simitthus / Chemtou labor and quarry camp. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2005, ISBN 3-8053-3461-3 , p. 76.

- ^ René Cagnat: L'armée romaine d'Afrique et l'occupation militaire de l'Afrique sous les empereurs . Imprimerie nationale, Paris 1912; Pp. 558-561; here: p. 560.

- ↑ Dating based on the title of Commodus. See: Gerhild Klose, Annette Nünnerich-Asmus (eds.): Frontiers of the Roman Empire , Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2006, ISBN 978-3-8053-3429-7 , p. 65.

- ↑ CIL 8, 11048 . Reading and completing the last two lines is very uncertain.

- ↑ CIL 8, 22761 .

- ↑ a b c Michael Mackensen : The small fort Tisavar / Ksar Rhilane from the Commodus period on the southern Tunisian "limes Tripolitanus". In: Kölner Jahrbuch. 43 (2010), pp. 451-468; here: p. 453.

- ↑ CIL 8, 22759 .

- ^ Erwin M. Ruprechtsberger: The Roman Limes Zone in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, Tunisia - Libya. (= Writings of the Limes Museum Aalen. No. 47). Society for Prehistory and Early History in Württemberg and Hohenzollern e. V. (Ed.), Winnenden 1993. P. 14 and P. 29.

- ↑ CIL 8, 22763 . Centenarium Tibubuci at 33 ° 12 '58.07 " N , 9 ° 48' 1.35" O .

- ^ Antonio Ibba, Giusto Traina: L'Afrique romaine. De l'Atlantique à la Tripolitaine (69-439 ap. J.-C.). Editions Bréal, Paris 2006. ISBN 2-7495-0574-7 . P. 154.

- ^ David J. Mattingly: Tripolitania. Taylor & Francis, 2005, ISBN 0-203-48101-1 , p. 130.

- ↑ G. J. F. Kater-Sibbes: Preliminary catalog of Sarapis monuments. EJ Brill, Leiden 1973, ISBN 90-04-03750-0 , p. 141.