Ulrich Schmidl

Ulrich Schmidl or Schmidel , the sources also Utz Schmidl (* 1510 in Straubing , † 1580 / 1581 in Regensburg ) was a German mercenary in the service of the conquistadors , patrician , explorer , chronicler and councilor . Along with Hans Staden , Schmidl is one of the few mercenaries who have written down their experiences.

Life

Ulrich Schmidl was born around 1510 as one of three sons of the respected Straubing patrician and mayor Wolfgang Schmidl. He had studied mathematics and law in Ingolstadt at the then only Bavarian university. After completing his studies in 1504, he took the office of city treasurer in Straubing. He also served as mayor four times until 1511. Wolfgang Schmidl's older son from his first marriage - Thomas Schmidl - took over the mayor's office from 1524. Ulrich Schmidl, who, according to sources, calls himself Utz, comes from Wolfgang Schmidl's second marriage.

Otherwise, little is known about his youth. After graduating from Latin school, Ulrich could certainly have achieved higher dignity because of his name, but he probably served as a Landsknecht in the Habsburg Empire under Charles V, which also makes sense due to the political situation in the German Empire at that time (fight against Franz I. of France, fight against the North African Moors and Turks , who besieged Vienna for the first time in 1529), precipitation of the great German peasant uprising in 1525.

After the expedition

Motivated by a letter from his brother Thomas, Schmidl returned to Straubing on January 26, 1554 with a few pieces of booty. Thomas died on September 20, 1554, and Ulrich inherited his late brother's fortune and became a councilor. From 1557–1562 he wrote his travelogue, known today as the “Stuttgart Manuscript”. Because he professed Lutheranism, however, he had to leave Straubing and went to Regensburg in 1562, where he made great fortune until his death in 1579.

Awards

In 1986 the then Foreign Minister Willy Brandt and Straubing's Lord Mayor Hermann Stiefvater inaugurated a memorial in Buenos Aires, since Schmiedl had co-founded the city in 1536.

Travel to the La Plata area

overview

We only learned more about Schmidl from 1534, when he took part in an expedition to what is now Argentina ( Río de la Plata ) as a mercenary under Pedro de Mendoza from Cádiz in Spain, together with around 3,000 other soldiers . Schmidl lived and fought there for almost 20 years and became a co-founder of Buenos Aires in Argentina in February 1535 and Asunción in Paraguay . His journey took him over the Río Paraná and Río Paraguay to today's Paraguay. From there he undertook several expeditions into the Gran Chaco , which took him up to southeastern Bolivia . In 1567 he wrote a report in German about his experiences on the Río de la Plata , which was published in Nuremberg in 1599 as true histories of a wonderful shipping , which made him, together with Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, the first historian of Argentina and Paraguay.

Destination of the expedition and client

Although at that time only two Spanish fleets had ventured into the La Plata area (one under the direction of Juan Díaz de Solís and another under Cabot ) and the yield of the two sailors was rather meager, the Spanish Emperor Charles V. just like the conquistadors themselves to the statements of the Indians from whom they had stolen the treasure that they had conquered the things (mainly silver jewelry) from a distant kingdom in the west. One could not have suspected that it was barter goods or first samples of the as yet unknown Inca empire and gave the river on which both expeders had moved the deceptive name "Rio de la Plata" ("Silver River"). The silver pieces aroused fantastic ideas of the supposed silver country Argentina after Cabot's return in 1530 with only one ship and half of its original crew.

Emperor Charles V wanted to finance his costly wars by stealing these promised treasures and by using local compatriots to curb the expansion of the Portuguese in Brazil. So Pedro de Mendoza sends a wealthy courtier with a fleet of 260 men on his way. One of the 14 caravels is provided by the Augsburg global trading houses Jakob Welser and Sebastian Neidhart . They manned their ships with employees and mercenaries, including people from Antwerp and other places. So does Ulrich Schmidl. He himself reports:

"2500 Spaniards and 150 High German, Dutch and Saxons were also waiting to start the journey under the orders of the officer, Captain Pedro de Mendoza."

On August 24, 1534, the Sanlúcar de Barrameda fleet left the seaport of Seville.

Documentation of the trip

With this report of the going on board Schmidl begins his diary-like record of his experiences on the Río de la Plata.

Neither the Munich, Hamburg nor Stuttgart manuscripts represent the printing copy, but they are so closely related that they probably go back to a joint manuscript that has now been lost.

A total of four manuscripts are known, the Stuttgart, the Munich, the Hamburg and the Eichstätter.

The Stuttgart handwriting

It is assumed that the Stuttgart manuscript represents Schmidl's handwritten travel report, which he had bound in 1554 but never brought to a printer. Today the manuscript can be found in the manuscript department of the Württemberg State Library in Stuttgart. This original consists of 112 sheets in four bundles. It bears the name:

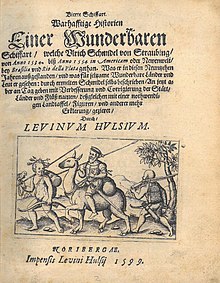

“True histories of a wonderful type of ship / which Ulrich Schmidel von Straubing / from Anno 1534 bit Anno 1554 in Americam or Neuenwelt, near Brasilia and Rio della Plata. What he was not able to do in these nineteen years and what strange wonderful countries and people he saw: through what Schmidel himself described To now but give day with improvement and correction of the places / countries and liquid names / the same with a necessary country table / figures / and another more explanation adorned by Levinum Hulsium. "

In addition to the above-mentioned transcript, several more have been created over the years. The most recent transcription is from Franz Obermeier from 2008 with a comment.

Nevertheless, three copies were probably made in the 16th century, the Munich, Hamburg and Eichstätter manuscripts. But nobody copied the Stuttgart manuscript. This remained unknown for a long time and was only published by Johannes Mondschein in 1892.

The Munich manuscript

The Munich script was published by Valentin Langmantel in 1889. Until Edmundo Wernicke revised this thesis in 1938, the Munich manuscript was considered to be the one originally written by Schmidl. The original is kept in the Bavarian State Library in Munich and consists of 69 sheets. It came to Munich from the Regensburg City Library in 1811. It is not a copy of the Stuttgart manuscript. Many sections are distributed and names are often highlighted. Editorial revisions were also made. The writer of the Munich manuscript must have been well educated because he independently makes additions to Schmidl's descriptions in the form of causal relationships. The title of this manuscript is:

“Anno As a man Zelltt After Christ Our Lady Lovers vnnd Seligmachers Gespurdt Taussett five hundred thirty-four I have seen Ulerisch Schmidl vonn Straubind this following Nacionn and Lender from Andorff from perahare as Hispaniam Indiam and some Innssell. With a healthy risk of warfare he went through and pulled through what tear (so piss on the fourth and fiftieth year from the senior year, God who had helped me to land again) I next to him, so I feel like mine with him admitted and met on the briefest hirinen described "

This script was also transcribed. For example by Markus Tremmel under the title "Ulrich Schmidl Fahrt in die Neue Welt" from 2000.

The Hamburg handwriting

The Hamburg version is in the Hamburg State and University Library . According to Lehmann-Nietzsche, the document dates from the second half of the 16th century and came as a gift from the Wolf brothers with other documents to the said library. It comprises 167 pages: Nietzsche describes that the Hamburg manuscript is a copy of an older one, but that it is more similar to the Munich version than the Hamburg original. Changes were made to a similar extent as in the Munich manuscript compared to the presumed original. The title also makes this clear:

"Anno Alls one after Christ our dear Lord and Seligmacher, born thousand, five hundred thirty-four, I have Ulrich Schmid von Straubing These successive nations and Lender von Antorff from Peragirt Alls Hispaniam, Indiam and some islands, with special dangers Inn Krigs run through and pulled. Elche Raiß, so from the upper 34 year out bit on the fifty-fourth (do God the Almechtig helped me against the land) And so 20 years has resisted. Me next to that. So my companion, Inn, sampled the same admitted and met. Described briefly here. "

The writing style makes the manuscript distinguishable from all others. A relatively recent transcription can be found in the 103rd annual report of the Historisches Verein Straubing from 2001.

The Eichstätter handwriting

The Eichstätt manuscript has not yet been published and is kept in the Eichstätt University Library. The fragment probably originated in Nuremberg between 1570 and 1575 and reached the prince-bishop's library in Eichstätt in the first third of the 18th century at the latest. It comprises 258 sheets, whereby Schmidl's text is only one of eight independent works. According to Klaus Walter Littger's opinion, this manuscript shows no stylistic resemblance to the other copies. The chronological sequence of the narrative, however, is the same. But the last pages are probably missing here (the manuscript ends abruptly and with a sentence that is atypical for Schmidl).

Comparison of the four scriptures

If you compare the three scripts, you can see the following:

The arrival of the troops at the Rio de la Plata is set to the year 1535 in every version, but the Stuttgart manuscript also indicates the Epiphany and allows us to date it more precisely.

The attack by the 23,000 Indians on Buenos Aires on St. John's Day 1535 is identical in all four fragments. The reports about the cannibalistic compulsions among the Spaniards during the famine in 1535 are just as coherent. But only the Stuttgart manuscript describes the case of a mercenary who ate his deceased brother.

With regard to the dissolution of the Corpus Christi garrison, the four manuscripts only disagree on the number of Spaniards who hung the Tiembus Indian chief. (In the Stuttgart script, in addition to the three people named in the other scripts, a priest is also present).

These nuanced deviations and yet again great consistency between the four manuscripts on Schmidl's trip to the La Plata countries extended to the last chapter.

Content of the travel description

The edition of Levinius Hulsius from 1602 contains 55 chapters, the contents of which are briefly illustrated below.

Chapter 1

On Bartholomew's Day , August 25, 1534, the fleet moved to Sanúcar, 20 miles from Seville. Unfavorable winds result in a disproportionately long lay time.

Chapter 2

On September 1st, 1534, the ships of Pedro de Mendozas started Charles V for the first Adelantado, d. H. as his deputy in the area of the Rio de la Plata, for their 200-mile trip to the Canary Islands. The ship overhauls in the ports of Palma, Tenerife and Gomera took four weeks. During this time there was contact between crew members and the island population, who mainly operated sugar cane plantations. The German ship could not follow the order to sail because the crew member Jorge de Mendoza, cousin of Adelantado, had smuggled an island beauty along with trousseau and maid on board. Only after the marriage did the captain Pieme receive permission to sail. But before that he chased the newlyweds overboard, because Jorge's action had brought the ship four hits from an island cannon.

Chapter 3

After a second two hundred mile stage, Santiago, the most important of the Viridis islands, one of the Cape Verde islands, was reached. The archipelago, which is 14 degrees north latitude, with its black population belonged to Portugal. After five days of berth, the ships were ready to continue their journey.

Chapter 4

Five hundred miles lie between the Cape Verde Islands and the island of Fernando de Noronha, which was called after two months. The uninhabited island had a dense bird population, and the trusting animals could be taken down with pieces. In his information on marine fauna, Schmidl mentioned: whales, flying fish, shabhats, which the Spaniards call "sumere", swordfish and sawfish.

Chapter 5

It was 200 nautical miles to the spots called Rio de Janeiro, for whose possession the Portuguese had to fight the French. The fleet stayed for 14 days with the Toupins who live here. Pedro de Mendoza had Juan Ossorio, to whom he had transferred his command due to illness, killed by officers Juan Ayolas, Jorge Lujan , Juan Salazar and Lazaro Salvago on the charge of intended inspiration. Schmidl considered the accusation to be incorrect and Ossorio, whose body had to be shown openly on board as a deterrent, to be innocent.

Chapter 6

One hundred and fifteen miles south of Rio de Janeiro, the fleet found the entrance to the 42-mile-wide La Plata Estuary (Paraná Wassú). Near San Gabriel, today's Uruguayan Colonia del Sacramento, the newcomers met the Zechuruas. The people lived exclusively on fish and meat. The only item of clothing was the women's cotton sham. Because the Spaniards could not get food from the poor Indians, they crossed Paraná Wassú, which is eight miles wide.

Chapter 7

When they arrived at the landing site, the landed unloaded their ships and founded Buenos Aires on February 2, 1536, surrounded it with a mud wall, built thatched huts and a permanent house for Pedro de Mendoza. The here nomadic living trunk of Charendies appreciated our chronicler to 2000 people. Food and clothing were the same as with the Zechuras. Because of a lack of water, the Charendis drank the blood of killed animals, and they also ate the root of a species of thistle against thirst. They shared the little food they had with the troops for 14 days. Then they moved four miles. Three Mendoza agents who were supposed to urge them to return were beaten. Thereupon Pedro de Mendoza ordered - according to Schmidl - 300 farmhands and 30 horsemen - including I was one of them - under the leadership of his brother Diego de Mendoza, to liquidate all carendies and to destroy their spots.

Chapter 8

The Spaniards lost 26 people, including Diego de Mendoza and six officers from the Spanish aristocracy, in the fierce opposition to the Carendies, which were reinforced by 1000 Indos. The weapons of the Indians were bows and arrows, spears with fire tips, and the "boleadoras". [...]

Here the facsimile breaks off until chapter 11. But this is only partially shown:

Chapter 11

[…] Zechuruas and Timebus [probably: attacked] Buenos Aires . With the help of arrows that did not go out after shooting, all huts were set on fire with the exception of the house of the Adelantado. Four ships also caught fire. Only shots from the ship's cannons drove the Indians out. "To thank God Almighty," said Schmidl, "that only 30 Christians perished on St. John's Day in 1536."

Chapter 12

After taking over the supreme command of Pedro de Mendoza, Juan Ayolas ordered a draft. The count showed only 560 mercenaries, 400 boarded the eight equipped river boats. 160 men remained in Buenos Aires to guard the four ocean-going ships with provisions that would last for a year if the ration per man per day were fixed at 133.6 g bread.

Chapter 13

Ayolas and his 400 men reached the Tiembus people after two months after an eighty-four mile journey - on which 50 soldiers again starved to death. On sixteen-seat dugout canoes 80 shoe long and three shoe wide, the Indians, led by their chief Zechera Wassu, met them peacefully up to four miles from their "settlement".

After this was presented with a shirt, a red biret and a fish hook, the people of Adelantado Ayolas were allowed to enter the village. They called him "Buena Esperanza" or "Corpus Chrsiti". Here they were given sufficient amounts of fish and meat, the only food of the tribe. The Teimbus were tall and straight in shape. The men went naked, the women wore a chamois. Schmidl describes them as "very shapeless" and always scratched on the face "and always bloody". The tribal jewelry consisted of small blue and white stone in the shape of a star on either side of the nose.

Chapter 14

During the Ayolas people's 4-year stay in Buena Esperanza, Pedro de Mendoza tried to return to Spain, but died on it. But he could still arrange for the Catholic majesties to send two auxiliary ships with everything necessary to the Rio de la Plata. Schmidl prayed for Mendoza's salvation.

Chapter 15

One of the auxiliary ships was led by Alonzo Gabrero. 1539 it reached Buena Esperanza with 200 new soldiers and food for two years. Immediately a ship started on a report trip to Spain. With the new ones, Ayolas now had 550 men. 150 remained with the Tiembus under Carolo Dobera. He drove up the Paranà with 400 men

Chapter 16

On eight brigantines , the troops searched for the Cairos on the banks of the Paraguay, whose foodstuffs also included corn, fruit, the three South American camel species, deer, chickens, wild boar and geese. But after four miles they met the Curendas. The 12,000-man tribe was v. a. warlike. In terms of their food, their jewelry, their clothes, and their physical appearance, the Curendas were like the Tiembus. In exchange for furrier products, the Indians received the usual trinkets from the Spanish . When the latter left after two days, the Curendas gave them two prisoners from the Carios people as scouts and interpreters.

Chapter 17

With their help, Ayolas reached the Gulgais people of 4000 souls after 30 miles. The Gulgais resembled the Teimbus and Curendas in jewelry, appearance, food and language. Their village was on a lake. The Spaniards were fed by the Gulgais for four days. Schmidl estimated the following tribe of Macourendas to be 18,000 warlike men who knew how to fight primarily from the water. But they behaved peacefully. Our writer describes them as physically ugly individuals. They had their own language. On the fourth day of their stay, the conquistadors killed a man-size, yellow-black snake, an anaconda, 35-shoe long, which was consumed by the natives. It had eaten many tribesmen.

Chapter 18

After four days the conquistadors had covered the 16 miles to the Zennais Saluaisco. These were small and stocky and had a good food supply because they also ate a type of guinea pig. The 2,000 tribesmen went completely naked. The Mepenes tribe of 10,000 souls, with whom the Spaniards met after 95 miles, turned out to be hostile. The warriors drove towards the troops on twenty dugout canoes and showed themselves to be agile fighters on the water. Even so, they suffered great losses. But the Spaniards could not capture anything after the battle in their village, and they could no longer get at the retreating Indians either. Out of anger about this, the mercenaries destroyed at least 250 watercraft.

Chapter 19

After eight days the conquistadors had covered the forty miles to the Cueremagbas. These lived on a small food base. The women wore shamrocks. The men were adorned with a parrot feather worn through a pierced nostril, the women a permanent blue tattoo on the face.

The troops had traveled 35 miles when they met the Aygais, who proved to be excellent warriors on the water. 15 Spaniards died in the fierce battle. There was no spoil for either side. Its river, the Tucumàn, has its source in Perú. Schmidl later announced further information about the further fate of the Aygais and provides this in Chapter 22.

Chapter 20

Fifty miles from the Aygais was the land of the Carios. It was an impressive size. The very broad nutritional basis guaranteed an abundance of food: the Carios had all previous meat animals, honey, various types of roots and potatoes. They were also cannibals who fattened their victims before they ate them in a feast. The Carios grew cotton and made wine. The male jewelry was a yellowish crystal set in the corner of the mouth. The women were objects of sale and exchange for the male family members.

Chapter 21

Thanks to a fortress-like structure, Lampere, the capital of Cariosland, was able to hold out against the Spaniards for three days. Then the 4,000 defenders asked for peace. The peace was sealed with the handover of six women to the Adelantado and two to each soldier. The losses amounted to 300 carios and 16 mercenaries.

Chapter 22

The Ayolas people built Asunción near the city of Lampere in 1539 with the help of the Carios. From here it was 50 miles to Aygaisenflecken and 334 miles to Buena Esperanza, the place of the Teimbus. Together with 300 mercenaries, 800 Cairos attacked the Aygais, their mortal enemies, and killed them all, as was the custom with the Cairos after defeating their enemies. Very few survivors were granted grace after four months, as ordered by an imperial decree, which Schmidl does not substantiate. He just lets us know that “every Indian should be pardoned up to the third time”.

Chapter 23

During a six month rest period in Asunción, Ayolas was informed about the Piembos tribe, who lived 100 miles away, and a campaign against them was prepared. The basic food was the usual, just fish and meat. The Piembos made a drinkable wine. Ayolas learned that after 80 miles when he passed Weibingo, the last town in Cairosland, he could stock up on his 300 people on the way to the Piembos.

Chapter 24

Because Ayolas was warmly received by the Piembos in the camp of the Piembos, 12 miles north of Weibingos on the Bogenberg, he and his group, reinforced by 300 Piembos, immediately set off for the Caracaris after he had ordered Irala not to join his 50 men for more than four months waiting for the ships to return. After this period has expired, Irala has to return to Asunción immediately with the two ships.

Chapter 25

Ayolas and his people found a peaceful reception with the next tribe, the Naperus. The same thing happened with the Peisennos. But due to supply difficulties, Ayolas ordered the Peisennos, with whom he left three sick mercenaries, to return to the Naperus so that the mercenaries could recover. After three days the departure to the Piembos followed. Halfway there, the troops were worn down to the last man in a joint attack by Naperus and Piembos.

Chapter 26

It was only in Asunción that Irala and his people learned of an Indian, whose language skills had ensured his survival, of the fate that the Naperus and Piembus had prepared for the Ayola troops. Nobody believed him for a year. Two Piembuses who got into Irala's hands confirmed the news under torture. They were killed by fire because they had to admit they were involved in the killing of the Spaniards. Irala was elected provisional Adelantado by the Landsknechts.

Chapter 27

Irala immediately ordered the amalgamation of the 460 soldiers distributed over three garrisons in Asunción. The 150 mercenaries who had remained in Asunción with their four brigantines were given responsibility for carrying it out. Before the 150 soldiers from Asunción took over the 250 soldiers from the Teimbus garrison, the captain Franco Ruyz and Juan Pavón, a priest and the secretary Juan Hernández left the Teimbus, the chief of the Tiembus, Zechera Wassu, and a few other Indians in the village murder, although - according to Schmidl - this tribe had done the Spaniards a lot of good. Irala, who took the three Spaniards with him, forbade Hauptman Antonio Mendoza to provoke the Tiembus, whose vengeance he was sure of.

Chapter 28

Trying not to make a mistake, the captain just mentioned fell into a trap of the sub-chief of the Tiembus, Zuche Liemi, and helped the aforementioned ruse to achieve complete success. All 50 compatriots who were “trapped” found their deaths, which Schmidl reported with a macabre sense of humor by writing that the Tiembus “were so blessed that the Spaniards were served food so well that none of them got off”. The 40 mercenaries who remained alive in Corpus Christi (also called Buena Esperanza) defied the siege by the Tiembus for 24 days. Then they retired to Buenos Aires. Irala's horror was great at this end of the garrison in Corpus Christi.

Chapter 29

After Irala's troops had spent five days in Asuncion, on the sixth day a caravel from Spain reached the port with the news that a second ship led by Alonzo Gabreres was in Santa Catarina, 300 miles away. Gonzalo de Mendoza then manned a galley with 6 Spaniards and Utz Schmidl to pick up the said ship. After two months, the cargo was reloaded onto the ship coming from Buenos Aires and both ships could begin their return journey.

Chapter 30

Because Gonzales de Mendoza overestimated himself, his ship was lost 20 miles from Buenos Aires. 21 sailors drowned. Six rescued themselves on driftwood and the sail tree, including Schmidl, who then had to march 50 miles overland to Buenos Aires. When they arrived they saw the ship Alonzo Gabreros, which had been in port for 30 days, and learned that they had been read for the funeral masses. The intercessions of the mercenaries saved the command of the disaster ship from the death sentence. The relocation of Asunción was carried out quickly and two years of rest followed.

Chapter 31

As successor to Ayolas, not Martin Domingo Irala was confirmed as Adelantado, but Avar Nuñez Cabeza des Vaca, who was sent by the emperor in 1542. He came with 4 ships, 400 mercenaries and 46 horses. He lost two of his ships off the Brazilian port of Santa Catarina and then took the land route to Asunciòn, which he reached after eight months. In the 300 miles he lost 100 soldiers. Because his imperial letter of appointment "only knew the priests or 2 or 3 captains", he had a very difficult time with the "Gmein" from the start.

Chapter 32

The inventory of the new governor showed a troop strength of 800 men capable of weapons. He confirmed Irala his previous powers, then he had nine river boats equipped for the greatest possible exploration of the Rio Paraguay. The captains Antonio Gabrereo and Diego Tabelino had to set out on a pre-expedition with 115 soldiers in three brigantines. They first met the Surucusis, whose men adorned themselves with a blue stone pierced into the corner of their mouth, the women only wore a shamrock. In addition to the usual staple foods, they ate peanuts. After the pre-expedition had entrusted their boats to the Surucusis, they undertook a four-day exploration into the interior.

Chapter 33

On the advice of the Carios , Cabeza de Vaca suspended a planned exploration upstream . Instead, he let Irala pull against the Dabero with a 400-man squad, which he reinforced with 2000 Cairos. Irala unsuccessfully reminded the chief of the Dabero of his peace duty, which he did not take seriously because he considered his fortified capital of the same name to be impregnable. During the four days of fighting and the subsequent storming of the capital, 16 Spaniards and an unknown number of Cairos died. On the side of the Dabero, 3,000 Indians were killed and most of the Dabero women with their children were taken prisoner. Irala had to comply with the following peace offer by the Daberos and the return of their wives and children.

Chapter 34

After Cabeza de Vaca had taken note of Irala's report, he started the previously canceled venture with 500 mercenaries and 2000 Indians. Juan Salazar y Espinoza commanded the 300 mercenaries left behind. On nine brigantines and 83 canoes we went up the river to the San Fernando mountains. Each brigantine now took two horses on board and they drove to the settlement site of the Piembos, who had fled after the destruction of their houses and supplies. For the next 100 miles the troops did not encounter any Indians, then the Bascherepos, then the Surucusis. Both peoples were friendly to them. The former owned a huge residential area and owned a large number of watercraft. The women wore a chamois, the men of the Surucusis, who lived 50 miles away and only settled as part of the family, had a wooden disc in their earlobe, the women a finger-length crystal in the corner of their mouth. You could call them beautiful. Their diet was the usual and they went completely naked. They didn't know anything about the Caracarais, what they said about the Carios wasn't true. For his land exploration, the Adelantado took 350 men, 18 horses and the 2,000 Carios from Asunción with him, 150 mercenaries had to guard the ships. Cabeza de Vaca had to stop the two-year exploration after just 18 days due to a lack of provisions. The follow-up exploration that Cabeza de Vaca attempted after the return of the pre-expedition carried out by Francisco Rivera had to be abandoned due to flooding. On this completely unsuccessful large-scale enterprise, because, according to Schmidl, "our colonel was not the man afterwards", the Adelantado made all officers and soldiers an enemy.

Chapter 35

Captain Rivera was sent upriver with 80 men, including Schmidl, to explore the Scheures, which also included the river environment, as far as it could be explored in two day's marches. After four miles they met the Guebuecusis, who inhabited a river island. They resembled the Surucusus in shape, and their food supply was plentiful. When they set out one day later, Guebuecusis escorted the troops in ten canoes and provided them with fresh fish and fresh venison twice a day.

The Ackeres, which the expedition encountered after 36 miles, for which it had taken nine days, were the largest Indians by shape to date. They only ate fish and meat, the women wore the usual chamois. With eight canoes, they replaced the Guebuecusis when the Spaniards moved on. The Ackeres are named after the native species of alligator they call "Jacarés". Despite the apt description, Schmidl thinks the animal is a fish.

Chapter 36

After nine days and 36 miles the troops had found the Scheures, a very populous tribe. As jewelry, they had a blue crystal in the corner of their mouth and an ear plug around which the ear was wrapped in a strange way. The men also wore gag beards. Her "clothes" consisted of a blue upper body painting. After four days with the vanguard, the Spaniards moved four miles towards the royal court, leaving their ships behind. On a path strewn with flowers, the king met them with an entourage of 1,200 men. The court orchestra played on instruments similar to shawls. By the time they reached the royal court, the hunters had killed 30 deer and 20 ñanus to the right and left of the path. Schmidl described the Scherues women as very beautiful and good lovers. They made large cotton coats with animal motifs that were used as blankets and pillows. When asked about gold and silver, the king gave the officer Rivera several pieces of precious metal that he wanted to have stolen from the Amazons . Immediately an Amazon expedition was decided. They estimated two months for the journey; this plan was accepted.

Chapter 37

Schmidl's description of the amazons is similar to that which we can read in Herodotus and many other authors. The Amazons only kept their daughters with them. Her sons grew up in the kingdom of King Jegnis. The news of the gold wealth of the Amazons, which was kept in the kingdom of King Jegnis, inflamed the Spanish greed for gold to such an extent that nothing could dissuade them from their plan to find it. So they did not allow themselves to be moved to turn back by the information from the King of the Scherues that they had just come at the time of the flood. Strengthened by local porters from the Scherues tribe, the troops waded through waist-high water on their way, which the soldiers also had to use as drinking water. With no rest or sleep, mostly without hot food, the mercenaries continued the Amazon expedition despite a terrible plague of flies. Then they met the Dilberis, who provided them with porters on the way to the Orthuesi. Twelve more days of marching through waist-high water were behind them when they got there. The Orthuesi formed the most populous tribe in the la Plata area. But when the conquistadors arrived, the famine raged. Now Rivera gave the order to withdraw.

Chapter 38

On the return march in Scheruesdorf, it was found that more than half of the mercenaries were terminally ill because of the lack of food and drinking water they had suffered. The following days are for relaxation. At the end of the fourth day of recovery, every soldier could look forward to 200 ducats that he had earned through barter deals. Cabeza de Vaca took this money from them on their return and arrested the expedition commander, Rivera. Schmidl took an active part in the successful revolt against the Adelantado that followed. He also had a hand in the later insubordination.

Chapter 39

According to our chronicler, Cabeza de Vaca's ruthlessness towards weakened mercenaries also revealed his lack of experience as a commander. During the two-month stay with the Surucusis, Cabeza de Vaca fell ill.

Schmidl described the land at the Tropic of Capricorn as the most unhealthy under the sun, in which no one could be older than 40 or 50 years. He was pleased that the constellation of the Great Bear reappeared, although it remained inexplicable to him.

The order of Cabeza de Vacas to exterminate the Surucusis found his disapproval because it was a matter of ingratitude towards the people and also of greater injustice. In Schmidl's eyes, the Adelantado had shown himself to be unsuitable for a leadership role.

Chapter 40

Our chronicler supported the community's decision to remove Cabeza de Vaca from office. The implementation by 200 mercenaries under the leadership of the three officers Alonzo Gabero, Franco de Mendoza and Grato Hermiego could only follow from the sickbed - like the re-election of Irala as Adelantado.

Chapter 41

The quarrels and open quarrels between the Spaniards after the deposition of Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca incited the Carios to rise up against the conquistadors. After fraternizing with the Aygais, Iperi and Bathaci, they gave the Spaniards a life-and-death struggle. In addition to the usual weapons, the Indians used a fish tooth to head and scalp their enemies at lightning speed. It made no difference to the warrior whether he scalped a dead or a living one. Scalptrophah had a long tradition among the Arios.

But because 1000 Iperi and Bathaci defected to the Spaniards, the mercenaries were saved from total defeat.

Chapter 42

Fifty-three mercenaries and the 1,000 indigenous people who defected to the Spaniards made their way to Asunción. After three miles, 15,000 Carios lined up for battle, which did not take place until the next day. After four hours of fighting, the Indians withdrew to the Froemidiere, four miles away, which had been converted into a fortress. They had prepared the town's buildings so that they worked like rat traps. 2000 Carios and ten soldiers fell. The Carios under chief Machkarias withstood the three-day siege. The so-called rondel tactic of the Landsknechte - a rifleman between two Indians under a tapestry shield - finally brought success. The survivors of the following massacre fled 20 miles to the village of Caraieba. Irala prepared to storm the place from three sides. After the wounded were taken care of and the relief arrived, Irala numbered 450 mercenaries and 1,300 Iperi and Bathaci. The four-day siege of Carieba was unsuccessful for the Spaniards. But the betrayal of an indigenous man still made the capture possible and another massacre followed. The surviving Carios found refuge with Chief Dabero in Luberic Sabaie. At first, Irala did not let the Indians go there, but instead ordered his soldiers to rest for four days.

Chapter 43

The expedition to Dabero was prepared during a fortnight's stay in Asunción. With nine brigantines and 250 canoes, Irala's fighters covered the 46 miles up the Rio Paraguay. Two miles from the place, the Adelantado had Irala stop and two Indians delivered the call to surrender to Dabero. Both parliamentarians were beaten up and sent back. No soldier would have been able to cross the river protecting the place without fire protection from the cannons. The patch was stormed by the mercenaries. In the subsequent massacre, however, on Irala's orders, the women and children were captured, but spared. Finally Dabero asked for mercy. It was granted to him and returned to women and children. From 1546 onwards the peace was permanent.

Chapter 44

This was followed by two years in Asunción, during which the imperial family in Spain proposed Iral to be elected Adelantado. In 1548 he set out with 350 mercenaries and 2000 Carios on seven brigantines and 200 canoes for the large company "Sierra de la Plata". At Mount San Fernando, he sent five of the brigantines and all of the canoes back to Asunción. Between brigantines with a crew of 50, led by Franco de Mendoza, orders were given to wait two years for the people of Iral to return at San Fernando. The troop, which consisted of 300 mercenaries, 130 horses and 2,000 carios, met a tribe called Naperus after 36 miles, which took them nine days. These lived only on fish and meat, the women wore the usual shame cloth. After one night with the Naperus, the troops continued their march.

The Maipais, the next tribe, were a master race that had subjugated a number of other tribes. Schmidl compared the relationship of the subjugated to the Maipais with that of serf peasants to their nobleman. The food supply of this tribe was very broad and there was an abundance of everything. We read about real honey forests and all year round harvest time. Our chronicler claims that the Maipais used the llama as a pack animal and mount. He reports on his own experiences with the llamas and also mentions that these animals spit. Schmidl deals extensively with the women of the Maipais and shows that they were very liberal with their sexuality. The 60-year-old Irala felt that they were also making demands, because the three “not old meatballs” left to him for the night ran away. Utz Schmidl comes to the conclusion that she was left to the wrong person.

Chapter 45

The attempt by 2000 Maioas to attack the Spaniards was answered by a three-day chase, during which 1000 Maipais were killed, but the escape of the majority of the tribesmen could not be prevented. The 3000 Indians that the Spaniards met in a piece of forest on the third day were not the Maipais they were looking for, but they had to die on their behalf. Schmidl was happy about 19 personal prisoners, because there were mainly young "Meidlein" among them. So entertainment was provided for the following eight days of rest. Since leaving Monte San Fernando the people of Iralas had covered 50 miles, and since leaving Naperus 36. Both the Zehmie, which they met after four miles, and the Tohanna, which they met after six miles, for which they needed two days, were subjects of the Maipais. In both places the conquistadors do not feed Indians, but food in abundance They covered 14 miles in four days, then they were with the Peionas. They left this tribe after three days, accompanied by an interpreter and a boy scout. After a quarter mile stage, these led the troops to the Mayegoni, from whom the Spaniards were provided with everything they needed. It was eight miles to the Morronos. Although these were friendly, after a day the Spaniards continued their journey to the Paronios, a small tribe four miles away, whose subsistence base was not good, to the Symannos, whose village was on a mountain in the middle of a thorn bush forest. it was twelve miles. The Symannos stood up to fight, but fled very soon, but not without first setting everything on fire. But there was enough food in the fields for the mercenaries.

Chapter 46

Sixteen miles separated the conquistadors from the tribe of the Barconos, who initially wanted to flee, but were then taken care of. After four days of rest, the twelve miles to the Leyhannos had to be completed. This took three days. The Leyhannos had been brought by locusts, which is why Irala had them marched off the next morning. It took the troops four days to make the 16 miles to the Carchoconos, which the locusts had also caused great damage. For the next 24 or even 30 waterless miles to the Suboris, the Carchconos gave the Spaniards large water supplies, but these were insufficient to prevent high losses through dying of thirst. Schmidl mentions a water-storing plant that ensured the survival of some. The next time the soldiers arrived in Suboris, panic broke out. An interpreter prevented the indigenous people from fleeing. After three months without rain, the Suboris were experiencing a severe water shortage, which the indigenous people met by preparing a manioc drink, among other things. Schmidl now had to guard the only well here and ensure the rationing of the water. Water was a reason for war between them. After two days the lot decided on the further advance. A few Suboris interpreters accompanied the troops, but fled bleakly, so that the soldiers did not arrive at the Peisennos until six days later, who fought back violently. After the storming of the spot, the Spaniards learned that the Peisennos had killed three mercenaries, who had survived Ayolas' expedition and had lived with them since then, the first four days before their arrival. Irala took revenge, only then did he order the departure to the Maigenos spot 16 miles away.

Chapter 47

On arrival after four days, the Spaniards met defensive Indians whose village, like that of the Symannos, was protected by a thorn forest and was located on a mountain. The Maigenos killed 16 Christians and a great many Cairos. When the mercenaries were in the village, the Migenso set it on fire and fled. There was no mercy for the Migenos tribesmen who fell into the hands of the Spaniards and their indigenous auxiliaries. 500 Cairos looked for the fled migenos and faced them to fight, but were trapped and had to ask Irala for help. This was granted promptly. 300 Cairos were killed, but so were countless Maigenos.

Four rest days followed with good care. Then they covered 52 miles in 13 days and encountered the Carcokies tribe after passing a large salt lagoon and determining the right route. From the salt lake, Adelantado Irala had sent a hundred-man vanguard to the Carcokies and assured them that the party was coming with peaceful intent. The tribe provided the entire troop with everything they needed, men and women each wore a jewel in the corners of their mouths. The beautiful women were dressed in a sleeveless shirt-like cotton cloak. There was a strict division of labor: the man had to bring in the food, the household was the woman's business.

Chapter 48

Although the boy scouts hired by the Carcokies ran away from the Spaniards after three days, they still found their way to the one and a half miles wide and very fish-rich Machasies River. Four mercenaries drowned while crossing with the help of quickly created quad rafts. When describing the area and the animal world, Schmidl mentions the puma as well as a flea-hard insect that laid its eggs through a stab wound in the feet of its victims. Worms grew in the eggs and ate off the toes of the stung if they were not removed in time.

From the town of Machcasie, Irala's people met Indians who, to their astonishment, spoke Spanish. Irala had advanced - without noticing it - into the area under Pizatto. According to astronomical calculations, the Spaniards had covered 272 miles as the crow flies since leaving Asunción.

Irala sent four mercenaries to Pedro de la Casca with a message of greeting . He wanted to avoid any trouble with the dreaded Adelantado, who shortly before had even had Gonzalo Pizarro , the brother of the conqueror of the Inca Empire, Francisco Pizaro , executed. After 20 days of waiting, Irala received a letter from de La Gascas with the order to wait with the Machsasies for further information. In truth, de La Gasca made a deal with Irala at the expense of the Landsknechte while he was waiting. After the bribery, which also included four messengers from Iralal who were supposed to visit La Gasca in Lima, Irala ordered the march back to Asunción. According to Schmidl's report, the outcome of the expedition was a complete disappointment for Irala's mercenaries. They had been so close to the silver at Potosi and had learned of the sums that had flowed into the emperor from Perú up to 1549 , but nothing of the wealth fell away despite the unspeakable hardships for the soldiers.

Chapter 49

In the fertile land of the Machcasies, which the Landsknechte had to pass through on the return march, Schmidl, in particular, made the honey trees enthusiastic again. Because of Irala's inept policy towards the tribe, the Machsasies forced the Spaniards to leave immediately. The Carcokies, already known to us, had left their place with their wife and child when the Spaniards arrived there. Against the advice of a few insightful mercenaries, including Schmidl, the Adelantado had the members of the tribe picked up and 1000 of them killed.

When the troops returned to the ships on Mount San Fernando after a year and a half, each had 50 slaves as booty. Upon their arrival, Irala and his people were immediately informed of an uprising in Asunción in the course of which Captain Diego Abriego, who had arrived from Seville, had the captain Franco de Mendoza, appointed by Irala as his deputy, beheaded.

Chapter 50

Diego Abriego did not want to submit to Irala , but was militarily forced to surrender. He did not accept his defeat, but waged a guerrilla war with 50 mercenaries against the Adelantado for the next year and a half . To restore peace, Irala married his two daughters to two of Abriego's cousins. So peace was restored.

A letter from Germany, which was delivered on July 25, 1552 on behalf of a Fugger factor Christoff Raiser, created a new situation for our chronicler: his brother Thomas demanded Utz Schmidl's immediate return home.

Chapter 51

After tough negotiations, Irala approved the vacation and commissioned Schmidl to deliver a report to Emperor Karl V. Because our Landsknecht had learned that there was a ship from Lisbon in São Vicente, he organized the return journey so that he could board it in the port mentioned Ship could go. The overland departure for São Vicente took place on December 26th, 1552: Schmidl set out on two canoes and with 20 Cairos as company. After 46 miles on the Rio Paraguay, landing stages of 15, then 16 and 54 miles followed. The tour company, which had grown by four deserters in the meantime, needed nine days for the latter route. After 100 miles on the Rio Paraná they reached Ginge, the last place of the Spanish crown in the land of the Carios.

Chapter 52

The land of the Toupin belonged to Portugal. It had taken the group six weeks to reach the spot the Toupin Cariesebas called. The Toupin always waged wars. Their prisoners were brought to a shed and locked up in a kind of wedding procession. Until they were slaughtered, their every wish was granted. Schmidl calls the Toupin way of life "Epicurean" because they were constantly drunk and had nothing on their mind apart from dancing and waging war. According to Schmidl, he was unable to describe the extent correctly. On Palm Sunday, two of the deserters from his travel company were eaten by the Toupin in Cariesebas. Some of the cannibals who later showed up at Schmidl and his group wore the clothes of the eaten. Schmidl and his troops were besieged by about 6000 Toupins for four days. They were ultimately able to flee and find safety through six days and nights of uninterrupted marching. Schmidl describes the situation at that time with the proverb: “Have a lot of dogs dead”. On the Rio Urquán they found provisions at the Biesaies. The snakes of the Rio Urquán were fatal for many people and animals. The team, weakened by poor nutrition and lack of sleep, was able to recover a little during a three-day stay with the Schebetuebas. Fortunately, they passed through the land of the French warlord Reinvielle without harm, and after six months of overland march of 246 miles, they arrived in São Vicente on June 13, 1553 with a prayer of thanks on their lips.

Chapter 53

After another 20 miles, the group stood in the port of São Vicente in front of the ship with which they wanted to start the return journey to Europe. On June 24, 1553 the anchor was lifted. Because the sail tree broke after 14 days, the ship had to call at the port of Espirito Santo, the residents of which lived mainly from growing sugar cane and cotton as well as marketing brazil wood. The sea between São Vicente and Espirito Santo was teeming with whales, whose fountains astonish the chronicler because of the amount of water expelled by the animals, which "goes into a good Franconian vass".

Chapter 54

After a four-month sea voyage, the Azores island of Terceira was called and provisions were stashed. Two days were enough for that. The crossing to Lisbon then took 14 days , at whose port Ulrich Schmidl arrived on September 3, 1553. There two of the 20 Indian travel companions of our chronicler died. He doesn't tell us what happened to the other 18 Carios.

After 14 days, Schmidl set off to cover the 42 miles to Seville. From there he continued the journey by ship to Sanlúcar, which lasted two days. Schmidl reached Cadiz in two overland sections via Porto de Santa Maira de Barramede. Here the returnees found a ship whose captain loaded his luggage but forgot about him. On another ship Schmidl started the journey to Antwerp in a convoy of 24 ships. The originally booked ship was lost and 22 people were killed. Several boxes of gold and all of Schmidl's luggage sank into the sea. Schmidl escaped the shipwreck due to the forgetfulness of the captain and stayed alive. Once again he had every reason to thank God from his heart.

Chapter 55

The 24 ships of the convoy, with which Schmidl continued his voyage, encountered the worst weather conditions. In the Bay of Biscay they got into such storms that the ships had to call at the port of the Isle of Wight to protect them. Eight of the 24 ships did not survive the storm and sank. The remaining 16 happily covered the 47 miles from Wight towards Antwerp. They remained at Arnemuiden 24 miles from Antwerp. Schmidl covered the rest of the route by land. He arrived in Antwerp on January 25, 1554.

In summary

The situation of the conquistadors was characterized by constant hunger and cannibalism . The campaigns of conquest yielded little and the death rate was very high. Schmidl describes the brutality of the raids in the Indian areas. Due to the small amount of booty, the conquistadors also fought among themselves. The raids went as far as Peru . Schmidl himself describes his behavior as a mercenary, which was a constant killing, a fight for booty and the enslavement of Indians.

Motivated by a letter from his brother Thomas, Schmidl returned to Straubing on January 26, 1554 with a few pieces of booty. Thomas died on September 20, 1554, and Ulrich inherited his late brother's fortune and became a councilor. Because he professed Lutheranism , however, he had to leave Straubing and went to Regensburg in 1562, where he made great fortune until his death in 1579.

Truth report or construct for entertainment?

If you look at Schmidl's descriptions from a different perspective, you can clearly see that between battle scenes, the ethnographic messages of around 30 Indian tribes are brought to the reader. These are all characterized by their nudity or half-clothing and by jewelry customs and the use of weapons. There are also longer text passages about customs such as “ cannibalism ” (Schmidl would have observed this in the Carios in today's Paraguay and the Tupi in Brazil) and “scalping”.

Similar descriptions can also be found in Staden's publication.

Schmidl's work was presented from 1567 as a "battle book" at the Frankfurt Book Fair as part of Brazil. Up to the 16th century: three German and two Latin versions were published, both of which were relatively successful on the market.

At the time of the Renaissance , especially at the end of the 19th century, after a brief downturn, the readership turned back to the history of the German Americana market at the end of the 16th century. At the time, this was largely known through leaflets that announced the brand new news about countries that had just been discovered.

In the first such publication ( Columbus letter 1497) anthropophagous island caribs of the Antilles region are addressed.

Amerigo Vespucci , Columbus' successor, already describes the locals as "ogres" and the reports about the cannibals on the northeast coast of South America and Brazil spread like wildfire, are translated into several languages and posted in words and pictures throughout Central Europe.

Mostly depicted are always sparsely covered with feathers, despising any religion, living in caves or makeshift huts of leaves, unrestrained and indulging in promiscuity, who chop up their prisoners like a butcher on the slaughterhouse. The enjoyment of eating meat is particularly emphasized.

In addition to these proclamatory leaflets, there were also publications that were aimed at a more demanding public. The brochure “Dis büchlin said” (1509) is particularly well known in this context. An unabridged translation of Vespucci's "Quatuor Navigationes" and probably the most detailed German Brazil before the middle of the century. But even here, the native people are generalized as primitive, man-eating gang. Vespucci has two examples of this image of the Indians, including a description in which one of his sailors was devoured by Indians before his eyes.

Sebastian Munster's 12-part map set, which is provided with a 16-page booklet, which should give a brief description of the countries and cities to be found on the maps (published in 1525, 1527, 1530), is another example of this almost clichéd publication. The description for the “new continent” in the booklet is underlaid with a picture of cannibals covered with feathers turning people on a spit. The accompanying text suggests the preference of the people depicted for this action. Accordingly, they would even fatten and breed extra people for it.

Münster's description of the world (1544–1628), a common opinion maker of the time, also fits in with this trend. The edition of 1550 shows unusual illustrations to this effect. In the accompanying descriptions, the author first lets Columbus discover the remains of cannibals. In the following he quotes partially verbatim from "Dis büchlin said" and concentrates exclusively on Vespucci's journey. But, according to the literature, this too was influenced by the work “Dis büchlin said”, more precisely its woodcut version, which shows Indians dissecting human parts with conical axes on a stone block.

In summary, one can say that both Stadens and Schmiedl's publications fit into the subject-historical discourse of their time. Even if they expand their knowledge of the new world considerably (the information offered by Staden is much more detailed than previous publications on the subject and the areas in Central America that Schmidl reports on are still unknown to the Germans), the terminology alone leaves it alone Associations arise and contrast brave Christians with wild, barbarians.

This tendency can already be seen in the foreword by the publisher Levinius Hulsius . Accordingly, the "barbarians" violate the most important institutions of Christian Europe:

“ These wild people would - clearly staged by the contact with the West like the Templus - by God and his commandments / by no merit / marriage / discipline / law / understanding / nor advice / never known nothing / but in all abgoetterey / Idolatry / Unfletterey / Fornication / Fuellerey / Man-eatingrey and uncleanness [...] have lived. "

In addition to unpleasant features, such as the female body beauty or exotic feather headdress, the appearance of the natives is sharply rejected by both authors and described as impure. They conclude that these people do not know any laws and do not trade.

The previous Americana research seeks answers to the question of why one wanted to bring such a people closer to the Europeans with so much emphasis and why the books were so successful. The main focus is on the relationship between the author's intention and the subsequently designed Indian image in politics.

Significant examples of this are the reports by Hernán Cortés , Petrus Martyr de Anglerias. Both leading conquistadors in the Spanish fleet. An obvious main aim of the reports is to legitimize conquest, submission etc. to the rest of Europe in the interests of the client (Charles V). Another author's intention could also have been to stand up to the propaganda of the so-called “ Leyenda negra ” against the expansionist Spain.

Schmidl's first encounter with Brazilian Toupins are described very fantastically. He is on an adventure for which further eyewitnesses are missing.

When Schmidl had to undertake a long walk through the territory of the Inido slaves in 1552 (see Chapter 51 ), he brought four men into play shortly before the border of the Portuguese America, the tribal land of the Toupin. These "wandering European deserters" want to organize provisions in the next Brazilian Indo settlement. But they are not returning from this company, instead, according to Schmidl's descriptions, Tiembus with " khlaider [n] der criesten ". Schmidl concludes that they were eaten by the Indians. According to the sources, the Straubinger had nothing to do with the Toupin, but describes the process of cannibalism exactly, which makes an exaggeration very likely.

The descriptions in the text are implausible. According to his own statements, he did not observe the process with his own eyes. Furthermore, the explanations about the Toupin are almost identical to the descriptions in Staden. In both descriptions, the Indians arrest prisoners during fights, prepare a festival and a wedding (see Chapter 52), fill vessels with alcoholic beverages and invite other settlements. Schmidl describes that the Toupin wore the clothes of his two colleagues who were sent out. Staden states that when he was captured, his clothes were ripped off, although the Tupi were otherwise unimpressed by textiles.

Something similar can be seen at the first encounter with the Carios (see Chapter 16 ). Here, too, is spoken of a fattening for the purpose of consumption. But then there are statements about the opposite treatment of beautiful women and old women and men. Although the Carios, as allies of the Spaniards, fought against other Indian tribes, Schmidl does not mention this second statement at any other point in his manuscript, but rather represents their brutal action against the opponents. At this point, similarities to already existing works can be seen:

The "Carta Martina about the mainland cannibals of the northeast coast of South America" has long been popular in Europe. According to this information, cannibals fatten male prisoners for consumption, women and old men are destined for work in the fields, young women have to provide fresh meat: Schmidl also depicts the erotic effect of the little gently captured Indian women.

So it seems likely that an amalgam of two cannibal Topoi of the New World was projected into an area still unknown to the public. Schmiedl writes in his will that he owned books. These books could have served as templates for his work. Many of the works mentioned above were published during or after Schmidl's trip. (Floriant Fries world map, Stadens Brasilianum, vvm.)

After Schmidl's return, these works could have served him as inspiration to write down his own journey. The focus on the "ogres" is intended to make his report interesting for the public. This would mean Schmidl's author's intention to be admired by the public as an expert and courageous fighter against the dreaded cannibals. In his remarks, he is also often directed at readers and at the beginning expressly introduces himself as Ulrich Schmidl von Straubing, which clearly implies that the text was written for a public audience. Schmidl probably had no doubts about the descriptions of Stad, which is why he also used it as a recipient.

The research presents Stadens and Schmidl's reports to date according to the author's intention. For the population of the time, the works certainly appeared credible, if only because of the educational and professional average of the authors, reinforced by their status as eyewitnesses, which is another motive than mere observation does not make it apparent. In addition, authors are mutually confirmed in their statements.

publisher

The above statements are reinforced by the fact that Schmidl gave his work to the well-known publisher Sigmund Feyerabend in 1567. Levius Hulsius first published the report in book form in 1599.

literature

- Georg Bremer: Among cannibals. The unheard-of adventures of the German conquistadors Hans Staden and Ulrich Schmidel ; Zurich 1996.

- Mark Häberlein: Schmidl, Ulrich. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 23, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-428-11204-3 , p. 161 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Carlo Ross: adventurer and rebel. Ulrich Schmidl and the discovery of Latin America. A novel biography ; Regensburg 1996, ISBN 3-927529-73-7 .

- Ulrich Schmidl, Josef Keim (ed.): Ulrich Schmidl's experiences in South America. After the Frankfurt printing (1567) ; Straubing 1962.

- Ulrich Schmidel: Adventure in South America 1535 to 1554. Edited from the manuscripts by Dr. Curt Cramer ; Leipzig 1926.

- Moonlight: Schmidl, Ulrich . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 31, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1890, p. 702 f.

- Heinrich Fromm: Ulrich Schmidl - Landsknecht, historian and co-founder of Buenos Aires ; Edition Stiedenrod, Wiefelstede 2010, ISBN 978-3-86927-115-6 .

- This fourth cruise. A true story of a wonderful boat trip that Ulrich Schmidl from Straubing undertook from 1534 to 1554 to America or the New World, to Brazil and the Rio de la Plata. Facsimile and transcription based on the edition by Levinus Hulsius 1602; Edition Stiedenrod, Wiefelstede 2010, ISBN 978-3-86927-113-2 and ISBN 978-3-86927-114-9 .

Web links

- Hans Holzhaider: The conquistador from Straubing on sueddeutsche.de October 18, 2016, p. R15

- Ulrich Schmidel a Landsknecht in the service of the conquistadors on kriegsreisen.de

- Literature by and about Ulrich Schmidl in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Dorit-Maria Krenn, Straubing City Archives: Ulrich Schmidl

- ↑ a b Dora Stürber: Ulrich Schmidl. Primer cronista del Río de la Plata ( Memento of March 13, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c d e f Bremer Georg: Among cannibals. The unheard-of adventures of the German conquistadors Hans Staden and Ulrich Schmidl . Zurich 1996, p. 92 .

- ↑ a b Bartolomé Miter: Ulrich Schmídel primer historiador del Río de la Plata. Notas bibliográficas y biográficas , Chapter 4 Biografía de Schmídel. In: Ulrich Schmídel: Viaje al Río de la Plata (1534–1554) ; Buenos Aires: Cabaut, 1903.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Beck Thomas: Columbi's heirs. European Expansion and Overseas Ethnic Groups in the First Colonial Age, 1415-1815 . Darmstadt 1992, p. 69 .

- ↑ Ulrich Schmidel: Viaje al Río de la Plata (1534-1554) ; Buenos Aires: Cabaut, 1903.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Fromm Heinrich: Ulrich Schmidl. Landsknecht, historian and co-founder of Buenos Aires . Wiefelstede 2010.

- ↑ Häberlein Mark: Schmidl, Ulrich . In: New German Biography . tape 23 , p. 161-162 .

- ^ Title page of Schmidl's travel descriptions in the edition by Leopold Hulsius, 1602 (Gäubodenmuseum Straubing, inv. No. 56821).

- ↑ Also on the following: facsimile and transcription based on the edition by Levinus Hulsius 1602; Edition Stiedenrod, Wiefelstede 2010, p. 1, p. 46 ff.

- ↑ Hans Holzhaider : "La Republica Argentina a su primer historeador" , Süddeutsche Zeitung of October 18, 2016, p. 35 (edition HBG).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Schmidl, Ulrich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Schmidel, Ulrich; Schmid, Ulrich; Schmidl, Utz |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German mercenary, patrician, explorer, chronicler and councilor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1510 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Straubing |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1579 |

| Place of death | regensburg |