Vallo Alpino

Vallo Alpino or Vallo Alpino del Littorio ( German Alpine Wall ) is the name of a largely unfinished line of fortifications in Italy in the Alps . Construction began in the late 1920s and officially ended in 1942; In some places, however, after the end of the Second World War in 1945, construction operations were resumed.

The line should secure the border regions to France , Switzerland , Yugoslavia and the German Empire (see article Alpenwall in Südtirol ). A large number of the systems are still preserved today. Streets, paths and bunkers are sometimes used for private, tourist or commercial purposes.

Surname

The name Vallo Alpino del Littorio is derived from the Liktor , the Roman bearer of the Fasces , and can therefore be translated as Fascist Alpine Wall . The German name is often used for the section opposite the German Empire, the Alpine Wall in South Tyrol .

The name "Vallo Alpino" results from the fact that this chain of fortifications was not given an official ( propaganda ) name, such as the French Maginot Line , the Siegfried Line or the Atlantic Wall . During their construction period, these were accompanied by targeted propaganda, which was intended to fool the enemy into strength and invulnerability. As a result, these fortification lines are now very well known to a wider public and their name says it all. The Italian fortifications, on the other hand - especially the fortifications in South Tyrol - were built under strict secrecy.

geography

The Alpine wall extends from the French-Italian border in the Maritime Alps to today's Rijeka (Italian: Fiume) in Croatia. Due to border shifts after the Second World War, a large number of the Vallo Alpino facilities are no longer on Italian territory, but in France, Slovenia and Croatia. The line of fortification is not actually a line that can be found lined up like a string of pearls (like the Atlantic Wall on the coast) along the Italian border. Since the high mountains largely separate Italy from its mainland neighbors, it is above all the passes and valleys of the access roads that have been paved. But there are also systems in the ridge regions near the passes, which are linked by a gigantic road network.

construction

The fortifications consist of a combination of obstacles of various functions, crew quarters, concrete bunkers and cavernous rock formations, all of which were built in tactically favorable locations within the Alps or the Slovenian Karst .

A distinctive feature is the imposing depth of the restricted areas. It extends up to 70 kilometers inland and can contain up to six blocks in a row. The barriers in the immediate vicinity of the border are structurally the oldest. The barriers are very different in terms of expansion and strength. Some barriers only have small bunkers for machine guns , others have artillery positions housed in the rock and armored trenches or walls that run through an entire valley. These barriers can include up to a dozen or more self-sufficient systems and are often located at natural obstacles in the valleys, at traffic junctions or include localities in the defense concept.

The current structural condition of the facilities varies greatly. There are still closed systems that can only be viewed with local approval. As a rule, many bunkers and rock caverns are open and represent sources of danger, especially if they are still unfinished. Some systems consist of hundreds of meters of tunnels, unsecured shafts and, in places, ailing access points that make orientation difficult and entry into which can be life-threatening. Often vegetation and well-preserved camouflage make it difficult to discover the structures.

history

After 1918

After 1918, military planners began evaluating the war and came to the conclusion that a future war would have to be countered with strong national fortifications on the borders. The well-known fortifications in France ( Maginot Line ), in Germany ( Oder-Warthe-Bogen , Westwall and Pommernwall ), in Greece ( Metaxas-Line ), Czechoslovakia ( Czechoslovak Wall ) as well as in Yugoslavia, Poland, the Soviet Union ( Stalin Line ), Switzerland ( Swiss Reduit ) and other European countries. Fortifications were not only expensive, many military also saw their military value in the face of new weapons and tactics as low and demanded that the funds be invested in the mobility of the armies.

In Italy, plans for a fortification of the newly won territories, especially after the peace negotiations in Paris in 1919, began before Mussolini finally came to power in 1926. In the event of war, according to the strategists, an enemy advance into Italy should be made more difficult to give the Italian army time to mobilize To provide. This should be able to close the incursion routes in the mountains with a relatively small number of border troops. This idea resulted from the Italian experience of the First World War and was later integrated into the planning of NATO after the Second World War . Many plants in South Tyrol and Friuli were completed and equipped after 1945.

Only the political and economic efforts of the fascist government made it possible to implement the plans. Construction was carried out simultaneously in the west on the border with France and in the east on the border with Yugoslavia. Before the actual fortifications could begin, hundreds of kilometers of new roads had to be built in difficult mountain terrain. This part already devoured a considerable part of the existing budget. Workers had to be recruited from southern Italy, means of transport provided and building materials procured. Since steel was scarce and mostly used for weapons production, the Italian engineers resorted to tried and tested solutions from the last war and were thus able to keep costs low. Wherever possible, tunnels were driven into the existing rock and only entrances and armories were built in the conventional bunker construction, although for the most part reinforcement steel was dispensed with. The interior furnishings were also spartan and the Italians did without elaborate technical equipment. In contrast to the well-known state fortifications such as the French Maginot Line or the German Siegfried Line, the Vallo Alpino was built without any accompanying propaganda program. Therefore, it is still one of the rather unknown fortification lines in Europe.

With the end of the western campaign in June 1940, work on the Italian Alpine border with France was also stopped. After the German-Italian Balkan campaign in spring 1941 , work on the Italian eastern border also ended.

The work on the Alpine Wall on the border with Germany, which began in 1938, continued despite the Berlin-Rome axis . The reason was a deep distrust between the Nazi regime and above all the Italian military. The gestures of friendship between the two dictators did nothing to change that. When the signs on the German side increased that the funds decided on from the “ Steel Pact ” between Rome and Berlin were flowing into the construction of the bunker, among other things, Hitler intervened directly in Rome. The construction was officially stopped; Barriers deeper inland were secretly built further, but were not yet ready when Wehrmacht troops occupied northern Italy in September 1943 (" Axis case ") to enable Mussolini to regain power ( Republic of Salò ) and for their own To continue to supply the front in the south. The fighting in some places was just a side note of the occupation.

In the cold war

After the Second World War, the French began in the west to destroy many facilities in the Vallo Alpino. In the east, the entire fortification area was now on the territory of the newly formed Yugoslavia. Only in the north did the plants remain on Italian territory. Some barriers were completed and should make a feared attack by the Red Army more difficult with the beginning of the Cold War . After all, Austria was still divided into four zones of occupation until the State Treaty of 1955 . To this end, some barriers were reinforced with armored turrets of discarded M4 Sherman and M26 Pershing . Until the fall of the Iron Curtain , the facilities remained a restricted military area; therefore, research on buildings is still relatively new. Many documents in the Italian military archives are incomplete or missing entirely.

After 1990

After the end of the Cold War , the military disarmed the facilities that were still in operation until 1990 and finally gave them up. In 1999 the military and the Italian state transferred numerous facilities to the ownership of the Autonomous Province of Bolzano - South Tyrol and the Friuli-Venezia Giulia region . Many former military roads and paths are now used as hiking trails, mountain bike trails and rural roads .

gallery

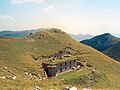

Barracks of the Vallo Alpino in a high alpine location on the Kreuzjoch near the Brenner Pass

Notch of the unfinished Vallo Alpino artillery works on the Gampen Pass in South Tyrol

Concreted shelter with a connection path to a bunker in the Vallo Alpino on the Plamort above the Reschenpass on the Italian-Austrian border

Connecting corridor in a larger fortification of the Vallo Alpino, which was expanded after 1945, near the South Tyrolean town of Gossensaß

Cusp line (here: wooden posts set in concrete with metal tips) near Graun in Vinschgau

Observation and machine gun stand of a Vallo Alpino factory on Lake Toblach in the Höhlenstein Valley in South Tyrol

Bunker near Malles

Bunker system on the Kreuzbergpass in Comelico Superiore

Fortification in Zgornja Sorica in today's Slovenia is part of the alpine wall

literature

- Alessandro Bernasconi, Giovanni Muran: Le fortificazioni del Vallo Alpino Littorio in Alto Adige. Trento 1999.

- Alessandro Bernasconi, Giovanni Muran: Il testimone di cemento. Le fortificazioni del "Vallo Alpino Littorio" in Cadore, Carnia e Tarvisiano. Udine 2009.

- Florian Brouwers: Il Vallo Alpino - The Alpine Wall. In: Fortification. No. 12, 1998, pp. 5-22.

- Florian Brouwers, Matthias Schneider: The eastern part of the Vallo Alpino between Postojna and Rijeka. In: Fortification. Special Edition 6, Fortifications in Italy (1), 2000, pp. 83-137.

- Hans-Otto Clauß: The Tagliamento Line. Fortifications of the Vallo Alpino in Carnia. In: Fortification. No. 21, 2007, pp. 95-109.

- Pier Giorgio Corino: L'opera in caverna del Vallo Alpino. o. O. 1995.

- Malte König: Vallo del littorio. The Italian defenses on the northern front. In: Fortification. Journal of the Study Group for International Fortifications, Military and Protective Structures, No. 22, (2008), pp. 87–92.

- Christina Niederkofler (Red.): Bunker . Published by the Autonomous Province of Bolzano - South Tyrol. Athesia, Bozen 2005, ISBN 88-8266-392-2 .

- Claude Raybaud: Les fortifications françaises et Italiennes de la dernière guerre dans les Alpes-Maritimes. o. O. 2002.

- Oliver Zauzig: The Vallo Alpino from Winnebach to Cortina d'Ampezzo. In: Fortification. No. 22, 2008, pp. 93-116.

- Rolf Hentzschel: The Alpine Wall in South Tyrol. Helios-Verlag 2014, ISBN 978-3-86933-109-6 .