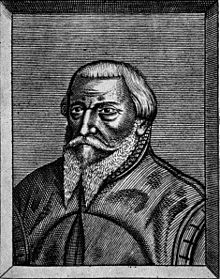

Veit Stoss

Veit Stoss (also: Stoss , Polish Wit Stwosz ); (* around 1447 in Horb am Neckar , Upper Austria ; † 1533 in Nuremberg ) was a late Gothic sculptor and carver . He was mainly active in Krakow and Nuremberg.

overview

Veit Stoss (also Stoss, Stosz, Stuosz, Stwosz) worked as a sculptor - works in wood and stone -, painter and engraver , especially in Krakow (1477-1496) and Nuremberg (from 1496 until his death in 1533), whereby he temporarily fled Nuremberg because of a conviction. In 1502 a Krakow document mentions the origin of "Vitti sculptoris de Horb"; he probably came from Horb am Neckar. Stoss may have been closely related to the Scheurl family from Nuremberg .

According to the Nuremberg historiographer Johann Neudörffer (1547), Stoss died in 1533 at the age of 95, but that is just as little guaranteed as the year of birth 1447 from other sources; it is likely that he was born around 1445-1450. It is not known where he received his training. His work shows influences from the Upper Rhine (Niclaus Gerhaert), other southern German (Ulm) and also Dutch influences.

It appears in the sources for the first time in 1477 when he went to Krakow to write about his first major work, the high altar retable of the St. Mary's Church there (until 1489) and other works, including the tomb of the Polish king Casimir IV Jagiello made of Adnet red check marble in the Cracow Cathedral (1492). Having become wealthy, Veit Stoss returned to Nuremberg in 1496, where he made stone and wooden sculptures, first the relief of the Volckamer Memorial Foundation with names and maker's marks (1499). From 1503 he was involved in lengthy court proceedings for forgery of documents; In December 1503, as a punishment, both cheeks were pierced with a red-hot iron. He was not allowed to leave the city without the approval of the council. Nevertheless, he fled to Münnerstadt in 1504 (where he painted his only known panel paintings), but returned voluntarily to Nuremberg in 1505, where he was arrested again.

A letter of grace issued by the later Emperor Maximilian I in 1506 was not taken into account by the City Council of Nuremberg. The council considered it difficult and contentious. Nevertheless, he was later (1514) allowed in the course of an imperial order to set up a casting workshop in Nuremberg in order to create figures for his tomb , which is located in the court church in Innsbruck . The Nuremberg patricians also continued to order works from him, outstandingly the “ English greeting ” in the Lorenz Church (1517/1518) by Anton II Tucher. His son Andreas, who was prior in the Nuremberg Carmelite monastery, commissioned his father in 1520 to create his last work, the high altar retable of the Carmelite Church (today Bamberg Cathedral), which was deliberately to remain without color (1520–1523). Veit Stoss died wealthy in 1533. He was buried in the St. Johannis cemetery in Nuremberg (grave St. Johannis I / 0268).

biography

After the completion of the Kraków Marian Altarpiece, he had achieved fame and prosperity in Poland. Nevertheless, for reasons not known in detail, he moved to Nuremberg at the beginning of 1496. Among other things, a serious illness of his wife was likely to have been decisive. She died in July 1496. In Nuremberg he also worked as a builder, e.g. B. On behalf of the council he planned a bridge construction over the Pegnitz, but this was not carried out. After the Jews were finally expelled from the Free Imperial City in 1498, Stoss acquired one of the expropriated houses in Sebald's old town in 1499 . Speculative transactions are guaranteed in Nuremberg. Shortly before 1500, Stoss relied on a recommendation for the cloth merchant Hans Starzedel given by a Nuremberg merchant he knew named Jakob Baner. In this context, the hesitant push received a kind of "guarantee" from Baner for the upcoming deal. What Stoss did not know was that Baner himself had invested 600 guilders with Starzedel and received his own money back from the merchant, who was in financial difficulties, through stoss' contribution. Starzedel stated that he would invest the sum of 1265 guilders brought in by Stoss in cloth, which he wanted to sell at the Leipzig trade fair at a high profit. When Starzedel's bankruptcy became apparent, a servant of Baner stole the surety from stoss' property. This was the record in his later confession to the city council.

When Starzedel had fled the city, Stoss sued the complainant baner and invoked the guarantee. The Council then requested this in the course of the process. Shock then made a forgery of the stolen document. He was convicted but pardoned. As evidence of his criminal act, both cheeks were publicly pierced with a glowing iron as a mark of shame . In addition, he lost his civil honor and freedom of movement . Veit Stoss' difficult life situation was exacerbated by the interference of his son-in-law Jörg Trummer, who considered his wife's family to be unjustly compromised, launched a feud against Jakob Baner and attacked the merchant trains of the imperial city on the way to the Frankfurt fair.

In 1497, Stoss married again. He had five children with Christine Reinolt. His son Willibald Stoss († 1573 in Schweinfurt ) was a picture carver and lived in Nuremberg until 1560. He had the sons Philipp and Veit Stoss.

Due to his ongoing efforts to publicly rehabilitate and his aggressive behavior, the Imperial City Council listed in a name register in 1506 as “ a restless haylosser burger who made an E. [honorable] advice vnd gemainer instead of vil Unruw” and in a decree as a "Wrong and screeching one" is called. Because of his outstanding talent, Stoss received several important commissions from influential Nuremberg citizens and also from Emperor Maximilian I , who helped him, among other things, to build his tomb .

His bust is placed in the Hall of Fame in Munich . The Stwosz Icefall in Antarctica also bears his name.

Create

Krakow period

He created in Krakow from 1477 to 1489 with the Cracow high altar of St. Mary's Church is the second largest carved winged altar of German Gothic . In the central shrine, the death and the Assumption of Mary are shown in larger-than-life, mostly fully rounded figures, while scenes from the life of Christ and Mary are depicted in reliefs on the wings . In the Marienkirche there is also the stone crucifix of the mint master Heinrich Slacker (1489). Probably after the death of the Polish king Casimir IV in 1492, Stoss made his tomb from Adnet red check marble for the cathedral in Cracow on the Wawel . Shortly afterwards, the marble slab of Archbishop Zbigniew Oleśnicki was made in Gniezno Cathedral .

Nuremberg period

Veit Stoss created in Nuremberg

- the so-called Volckamer epitaph (memorial picture, donated by Paulus Volckamer in 1499) in the Sebalduskirche ; a three-part stone relief depicting Maundy Thursday events

- the English greeting in the Lorenz Church , donated by Anton Tucher in 1517/18 , hanging from the vault of the choir, the figures of the angel and Mary in a rosary decorated with seven medallions

- the crucifix in St. Lorenz

- the Raphael Tobias Group, 1516, commissioned by Raffaele Torrigiani for the Dominican Church, Germanisches Nationalmuseum , Nuremberg

- the Bamberg Altar , commissioned 1520–1523 for the Carmelite Monastery in Nuremberg; because of the Reformation he first came to the Church of Our Lady in Bamberg, then in 1937 to Bamberg Cathedral .

Works

- High altar retable, Krakow, St. Mary's Church, 1477–1489.

- Funerary monument to King Casimir IV of Poland, Krakow, Cathedral on the Wawel, 1492.

- Grad monument for Archbishop Zbigniev Oleśnicki, Gniezno, Cathedral, 1496.

- Funerary monument for Bishop Piotr von Bnin, +1 494, Włocławek, Dom .

- Crucifix by Heinrich Slacker, Krakow, Marienkirche, around 1489.

- Volckamer Memorial Foundation, Nuremberg, St. Sebald, 1499.

- Virgin Mary statuette, London, Victoria & Albert Museum, around 1500–1505.

- Wooden model of the grave slab of Filippo Buonaccorsi (Callimachus), Krakow, Dominican Church, around 1500–1505.

- Painted scenes from the legend of Kilian, Münnerstadt, parish church of St. Maria Magdalena , 1504.

- Maria and Johannes from the Nuremberg Frauenkirche, Nuremberg, St. Sebald, 1506/7.

- Crucifix from the Hl.-Geist-Spital, Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, around 1500.

- St. Andreas, Nuremberg, St. Sebald, around 1507–1510.

- Annunciation to Maria, Wildenfels epitaph, Langenzenn, parish church, 1513.

- Raphael Tobias Group from the Nuremberg Dominican Monastery, Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 1516.

- Crucifix, Nuremberg, St. Lorenz, around 1516–1520.

- English greeting, Nuremberg, St. Lorenz, 1517–1518.

- House Madonna from Wunderburggasse, Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, around 1520.

- St. Vitus in the oil boiler , Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 1520.

- St. Rochus, Florence, SS Maria Annunziata, around 1520.

- Wickelscher crucifix, Nuremberg, St. Sebald, 1520.

- Pömerepitaph with the raising of Lazarus, Nuremberg, St. Sebald, outer wall, remains today Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 1520.

- Dragon chandelier based on Dürer's design , Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 1522.

- Drawing for the reredos of the Nuremberg Carmelite Church (visor), Cracow, Muzeum Historyczne Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, 1520.

- Retable for the Nuremberg Carmelite Church, Bamberg, Cathedral, 1520–1523.

- 10 copper engravings, of which only 35 impressions have survived: Raising Lazarus (8 copies), Pomegranate Madonna (6 copies), Lamentation of Christ (6 copies), Holy Family in the room (3 copies), Martyrdom of St. James (3 copies), adulteress before Christ (2 copies), Madonna in the room (2 copies), torture of St. Katharina (2 copies), Gothic capital (2 copies), St. Genovefa (1 copy).

- Großostheimer Krippchen, from the workshop of Veith Stoss, exhibited in the Bachgau Museum, 1492

- Marienaltar, from the workshop of Veith Stoss, created around 1498 for the Konradinisches Salzburg Cathedral , since 1885 in the Johanneskapelle of the Benedictine Abbey of Nonnberg

- St. Catherine, Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, around 1500.

literature

- Rudolf Bergau: The carver Veit Stoss and his works. Nuremberg 1884.

- Max Loßnitzer: Veit Stoss. The origin of his art, his works and his life. Leipzig 1912.

- Reinhold Schaffer: Andreas Stoss, son of Veit Stoss, and his counter-Reformation activity (= Breslau studies on historical theology. Vol. 5). Breslau 1926 (also: Dissertation at the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Bonn, 1923).

- Adolf Jaeger: Veit Stoss and his sex (= free series of publications of the Society for Family Research in Franconia. Vol. 9). Nuremberg 1958.

- The English greeting from Veit Stoss to St. Lorenz in Nuremberg (= workbooks of the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation. No. 16). Munich 1983.

- Rainer Kahsnitz : Veit Stoss in Nuremberg. Works by the master and his school in Nuremberg and the surrounding area. Catalog for the exhibition in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Munich 1983.

- Michael Baxandall : The Art of the Picture Carver. Tilman Riemenschneider, Veit Stoss and their contemporaries. Munich 1984.

- Germanisches Nationalmuseum Nürnberg / Central Institute for Art History Munich (Ed.): Veit Stoss. The lectures of the Nuremberg Symposium. Munich 1985 (with complete bibliography, pp. 297–338).

- Gottfried Sello : Veit Stoss. Hirmer, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7774-4390-5 .

- Rainer Kahsnitz: Veit Stoss, the master of the crucifixes. In: Journal of the German Association for Art History. Vol. 49/50, Berlin 1995/96, pp. 123-178.

- Dobroslawa Horzela (Ed.): Around Veit Stoss. Catalog Muzeum Narodowe, Krakow 2005, ISBN 83-89424-27-4 .

- Manfred Grieb (Hrsg.): Nürnberger Künstlerlexikon. Munich 2007, ISBN 3-598-11763-9 , p. [?].

- Paul Johannes Rée: Veit Stoss . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 36, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1893, pp. 466-471.

- Albert Dietl: Assumption of Mary. The Krakow St. Mary's Altar and its history. In: Christoph Hölz (Ed.): Wit Stwosz - Veit Stoss. An artist in Krakow and Nuremberg. Munich 2000.

- Gerhard Weilandt: The Sebalduskirche in Nuremberg. Image and Society in the Age of Gothic and Renaissance. Imhof, Petersberg 2007.

- Ulrich Söding: Veit Stoss. In: Katharina Weigand (ed.): Great figures of Bavarian history. Herbert Utz, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-8316-0949-9 .

- Nicolaus Heutger : Stoss, Veit. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 11, Bautz, Herzberg 1996, ISBN 3-88309-064-6 , Sp. 1-5.

- Gerhard Weilandt: Veit Stoss. In: New German Biography. Vol. 25, Stadion-Tecklenborg, Berlin 2013, pp. 458–461.

- Walter Folger: The Marien Altar of Veit Stoss in Bamberg Cathedral. Erich Weiß Verlag, Bamberg 2014, ISBN 978-3-940821-36-2 .

- Inés Pelzl: Veit Stoss. Artist with lost honor . Pustet, Regensburg 2017, ISBN 978-3-7917-2855-1 .

Exhibitions

- 2019/2020: heroes , martyrs , saints . Paths to paradise in the Germanic National Museum in Nuremberg.

Web links

- Literature by and about Veit Stoss in the catalog of the German National Library

- Film: The story of the Saffian shoe

Individual evidence

- ^ Germanisches Nationalmuseum : Online object catalog Archangel Raphael

- ↑ Germanisches Nationalmuseum: Online object catalog rosary panel (altarpiece)

- ^ Boleslaw Przybyszewski: The origin of Veit Stoss in the light of Krakow archives . In: Germanisches Nationalmuseum Nürnberg (Ed.): Veit Stoss. The lectures of the Nuremberg Symposium . Munich 1985, p. 31-37 .

- ↑ Adolf Jäger: Veit Stoss and his family . Neustadt / Aisch 1958, p. 19 .

- ↑ Ines Pelzl: Veit Stoss. Artist with lost honor . Pustet, Regensburg 2017, p. 62 .

- ↑ Thomas Eser: Veit Stoss - A Polish Swabian becomes Nuremberg. In: Brigitte Korn, Michael Diefenbacher, Steven M. Zahlaus (Eds.): From near and far. Immigrants to the imperial city of Nuremberg (= series of publications by the Nuremberg City Museums, Volume 4). Michael Imhof Verlag, Petersberg 2014, ISBN 978-3-86568-998-6 , p. 87.

- ↑ Ines Pelzl: Veit Stoss. Artist with lost honor . Pustet, Regensburg 2017, p. 81 ff .

- ↑ Ines Pelzl: Veit Stoss. Artist with lost honor . Pustet, Regensburg 2017, p. 89 ff .

- ↑ Ines Pelzl: Veit Stoss. Artist with lost honor . Pustet, Regensburg 2017, p. 70 .

- ↑ Willibald Stoss, son of Veit Stoss and 2nd wife Christine in: Gothic and Renaissance Art . P. 475

- ↑ Adolf Jäger: Veit Stoss and his family . Neustadt / Aisch 1958, p. 90 ff .

- ↑ Max Loßnitzer: Veit Stoss. The origin of his art, his works and his life . Julius Zeitler, Leipzig 1912, p. LIV .

- ↑ Max Loßnitzer: Veit Stoss. The origin of his art, his works and his life . Julius Zeitler, Leipzig 1912, p. LXXI .

- ^ Paul Johannes Rée: Veit Stoss . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 36, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1893, pp. 466-471.

- ↑ Rotscheck marble (= breccia of predominantly red-brown tubers in a white calcite filling) was a symbol of the transience of life; it was preferred for the production of epitaphs or tombs.

- ↑ Online object catalog Christ on the Cross , accessed on April 20, 2020.

- ↑ See: [1] , accessed on July 9, 2017.

- ^ Online object catalog Saint Catherine , accessed on April 20, 2020.

- ^ Germanisches Nationalmuseum : Heroes, Martyrs, Saints. Paths to paradise

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Push, Veit |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Stoss, Veit; Stwosz, Wit |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German sculptor and carver |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1447 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Horb am Neckar , Upper Austria |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1533 |

| Place of death | Nuremberg |