Wigalois

The Wigalois des Wirnt von Grafenberg is a courtly verse novel in Middle High German, which is counted among the literary series of Arthurian novels . Wigalois, the title character of the novel, is knight of the famous round table of King Arthur and son of the Arthurian model knight Gawein . The work, which was created between 1210 and 1220, enjoyed enormous popularity in the Middle Ages and was received as a popular book version until the early modern period .

Emergence

The origin of the Wigalois novel in the first third of the 13th century (around 1210/15, but no later than 1220) is now largely certain. On the one hand, the earliest surviving text witnesses of the work speak for this dating, which would rule out a later creation; On the other hand, the dating of the Arthurian novels by Hartmann von Aue and Wolfram von Eschenbach can also be used to locate the Wigalois in terms of time: These texts are already mentioned in the Wigalois - this means that the Wigalois can only have emerged after their origin or distribution.

Little is known about the author Wirnt von Grafenberg. All biographical information is based on references in the Wigalois, Wirnt's only surviving work, and on some mentions in other contemporary texts. Accordingly, Wirnt's origin from today's city of Graefenberg northeast of Nuremberg is likely; this is also indicated by the language and volume of the wigalois . Wirnt may have been a member of a ministerial family from this place or the immediate vicinity. Nothing is known about his training; However, there are some indications that the poet acquired theological knowledge and foreign language skills in a monastery school.

There is also no explicit information about Wirnt's client in the text or outside of it. The question of patrons was and is discussed extremely controversially in research. Considered were u. a. the princes of Andechs-Meranien (traditional research), the Zollern as burgraves of Nuremberg ( Volker Mertens ) and recently also the Stauferhof with its far-reaching dynastic connections (Seelbach / Seelbach). Due to the overall structure of the text and numerous intertextual references, it can be assumed that Wirnt wrote for a courtly audience with literary knowledge and specifically served the interests specific to this social group.

Handwritten tradition

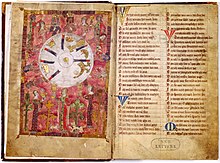

Wirnts Wigalois has survived comparatively richly with 38 complete and fragmentary manuscripts from the 13th to the late 15th century (for comparison: Iwein 32 manuscripts; Parzival 82 manuscripts). The oldest of these are two (incomplete) manuscripts from around 1220-30, which are written in Bavarian writing . The only two illustrated manuscripts that have survived are of particular importance: the manuscript B ( Amelungsborn , 1372, today in Leiden , UB, LTK 537), which has 47 miniatures to the text, and the manuscript k ( Hagenau , 1420 –1430, formerly Hofbibliothek Donaueschingen , since 2018 Badische Landesbibliothek ) from the workshop, which later became known as the Diebold Lauber workshop , with 31 pictures. The broad and long-lasting tradition testifies to the enormous popularity of the wigalois with the courtly public of the time.

The following tabular overview of the manuscripts known today (without fragments) is based, unless otherwise noted, on the descriptions in the continuously updated manuscript census .

| Repository | description | Sigle | Dating | Provenance | On-line | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cologne , Historical Archive of the City , Best. 7020 (W *) 6 | Text handwriting, paper | A. | 1st half of the 13th century | Digitized microfilm (b / w) | ||

| Bremen , State and University Library, msb 0042 | Text handwriting, paper | L. | 1356 | Digitized | ||

| Stuttgart , Württemberg State Library , Cod.HB XIII 5 | Text handwriting, paper | C. | around 1360-1370 | |||

| Leiden , University Library, LTK 537 | Illuminated manuscript, parchment | B. | 1372 | Digitized | ||

| Karlsruhe , Badische Landesbibliothek , Cod. Don. 71 | Illuminated manuscript, paper | k | around 1420 | 1. Donaueschingen , Fürstlich-Fürstenbergische Hofbibliothek , Cod. 71

2. Hamburg / Basel , private property Jörn Günther 3. Ramsen (Switzerland), private ownership Heribert Tenschert (until the end of 2018) |

Digitized | |

| Schwerin , State Library, without signature | Text handwriting, paper | l | 1435-1440 | Digitized | ||

| Hamburg , State and University Library , Cod. Germ. 6 | Text handwriting, paper | N | 1451 | Digitized | ||

| Dresden , SLUB , Mscr. M 219 | Text handwriting, paper | U | around 1460 | Digitized | ||

| London , British Library , MS Add. 19554 | Text handwriting, paper | Z | 1468 | |||

| Vienna , Austrian National Library , Cod. 2970 | Text handwriting, paper | M. | 2nd half of the 15th century | Vienna, St. Dorothea, Augustinian Canon Monastery (Madas) | Digitized | |

| Křivoklát (Czech Republic), Castle Library, Cod. I b 18 | Text handwriting, paper | V | 1481 | 1. Donaueschingen, Fürstlich-Fürstenbergische Hofbibl., Cod. I b 18

2. Prague , National Museum, Cod. I b 18 |

||

| Berlin , State Library , mgo 483 | Text handwriting, paper | W. | 4th quarter of the 15th century | Cheltenham , Bibl. Phillippica, Ms. 16413 | ||

| Vienna , Austrian National Library , Cod. 2881 | Text handwriting, paper | S. | 15./16. Century |

Plot and structure

prolog

Some - but not all - traditions of the Wigalois contain a prologue in which the reader is addressed. The author asks for indulgence with the work and that the reader, as a beginner, should credit goodwill higher than that of an "art-experienced master". The first 13 of the 144 verses belonging to the prologue are:

Middle High German:

Who would have made me guoter ûf?

sî ez iemen of me kan

beidiu read and verstên,

the sol genade Begen to me

whether iht change sî me,

he daz me but laze VRI

valscher talking about: daz Eret in.

I weiz wol daz I niene'm

geliutert and gerihtet

still sô well

done michn velsche lîhte a Valkyrie man, if nobody wants

to protect himself in Kan

, as he did.

Translation to Seelbach / Seelbach:

What excellent person has opened me?

If there is someone who can

read and understand me ,

then may he - even if there is something

to criticize about me - treat

me kindly and

spare me defamation : this will honor him.

I know very well that I have not been

cleared up and straightened out

and that I have not been written so well

that a blasphemer can easily slander me;

because no one can

really protect himself from them , however skilfully he writes.

Narrative blocks

According to Schiewer (1993), the action of the Wigalois can be divided into four larger narrative blocks:

The first narrative block tells of the protagonist's parents' story, of his departure to search for a father and finally of his arrival and training at Artushof. A source cannot be proven, but similar narrative patterns can be found e.g. B. also in Wolfram's Parzival or in Hartmann's Gregorius : Wigalois' father is the Arthurian model knight Gawein, who marries King Joram's niece Florie in the fairy kingdom of King Joram. Gawein soon leaves his pregnant wife to return to the Artus Court. So Wigalois grows up fatherless. As a young adult he set out to look for his unknown father and to prove himself as a knight. He, too, quickly arrives at Artushof, where he is courteously brought up by Gawein without his father and son recognizing their relationship. Finally, Wigalois receives the sword line in a solemn ceremony . When the messenger Nereja appears at Arthur's court and asks help for her mistress Larie, Wigalois again asks the king to entrust him with this aventiure. Wigalois is granted the request and he hurries after the angry Nereja, who would have preferred to appoint an experienced knight.

A second narrative block describes a series of parole approvals that the hero has to pass in Nereja's company on the way to Roimunt, where Larie is staying. In this narrative sequence, Wigalois first defeats and kills an inhospitable host; This is followed by a helper aventiure for a lady from Arthurian court, who is freed by Wigalois from the hands of two giants; then the hero catches a puppy, gives it to the messenger and kills its owner. This is followed by the most extensive part within the narrative block: On behalf of Princess Elamie of Persia, who was cheated of a beauty prize, Wigalois wins a court battle over the red knight Hoyer von Mansfeld. Eventually, the hero defeats a competitor, King Schaffilun, who is also trying to win the major main venture of Korntin.

The third and longest narrative block then leads the hero into a demonic realm: Wigalois, who has proven himself qualified, is now supposed to free the realm of Korntin from the clutches of the pagan usurper Roaz and win it back as the rightful queen for Larie. If he wins, he is promised Larie's hand. The main aventure shows a distinctly historical and religious signature; Wigalois appears here as the savior in the fight against the un-Christian, evil. Right from the start, the described scene is strongly reminiscent of the historical theological argumentation in contemporary crusade sermons . Wigalois is equipped with magic weapons when he enters the world of the afterlife, first frees the realm from a cruel dragon named Pfetan and finally fights against the Roaz, whom he defeats. Thus, at the end of the narrative block, Korntin is a free country again.

The fourth and last narrative block follows the narrative pattern of the chanson de geste and, due to its political and geographical allusions, appears to be very historical. The starting point is the wedding and coronation celebrations of Wigalois and Larie. A herald appears there, who tells of the killing of a wedding guest near Namur. Without further ado, Wigalois as the new ruler undertakes a campaign against King Lion of Namur. After the victory, the hero hands the city over to a follower as governor. Then Wigalois and Larie pay a visit to the Artus Court. Then they return to their realm, where Larie gives birth to a son: Lifort Gawanides, who later becomes a famous hero like father and grandfather (a corresponding serial novel, the composition of which Wirnt announces, but wants to leave to another poet, has not survived ).

Source question and possible text genesis

The Wigalois is based on Romance models, but it is not - as earlier research suspected - a German adaptation of a French individual poem; It is more likely that Wirnt put together various French texts himself; only the second narrative block corresponds in relative detail to the Bel Inconnu by Renaut de Beaujeu (6266 verses; a manuscript; end of the 12th century). What is also important for the source question is a self-statement by Wirnt in the epilogue of Wigalois, according to which he owes the story told solely to the oral report of a squire (11686ff.); there is no need to doubt the credibility of this statement; however, it supports the thesis that the author of the Wigalois resorted to a rather heterogeneous repertoire of orally transmitted narrative patterns and converted them into a new work according to his own needs and aesthetic demands.

Etymologically, Wigalois could have originated from Gui li Galois (Guy from Wales, "Guido the Welsh").

The poet Albert Vigoleis Thelen used the Wigalois, which was borrowed from the Gawaniden novel of the Wirnt von Grafenberg (Wirnt von Grâvenberc) and transformed into Vigoleis, as part of the name since his first student attempts at writing.

reception

a) Reception in the High Middle Ages: The Wigalois is also mentioned in several other Middle High German poems, e.g. B. in the Diu Crône by Heinrich von dem Türlîn or in the Renner by Hugo von Trimberg . In Konrad von Würzburg's Der Welt Lohn , Wirnt von Grafenberg himself becomes a literary figure in that he appears there as a knightly servant of the woman world. In addition, a Wigalois reception is also passed down in the religious and didactic literature of the Middle Ages, for example in the Amorbach Cato (Disticha Catonis).

b) Reception in the early modern period: From 1455 there is a fragment of the only known strophic revision by Dietrich von Hopfgarten . In 1473 the novel was then dissolved into a prose version, which was printed by Johann Schönsperger in Augsburg. At least eight further editions were made up to the 16th and 17th centuries. In the 16th century there was even a Yiddish version that was translated into New High German at the end of the 17th century; the last offshoot of this branch of tradition was the satirical prose story “About King Arthur and the beautiful knight Wieduwilt” at the end of the 18th century . A fairy tale ” (1786); As early as 1819, a printed edition began the scientific study of Wirnts Wigalois.

c) Wall paintings: Around 1390 the arched hall of the so-called summer house at Runkelstein Castle was painted with scenes from the Wigalois on behalf of Niklaus Vintler . The wall paintings are executed using Terraverde technique and are related to other illustrations of literary subjects such as Tristan and Isolde from the same period in this castle.

literature

- Joachim Bumke : History of German Literature in the High Middle Ages , 4th, updated edition. Munich 2000, pp. 218-220

- Friedrich Michael Dimpel: Away with the magic belt! Disenchanted rooms in the 'Wigalois' of the landlord von Gravenberg . In: S. Glauch, S. Köbele, U. Störmer-Caysa (Ed.): Projection - Reflection - Distance. Spatial ideas and figures of thought in the Middle Ages . Festschrift for Hartmut Kugler. Berlin / Boston 2011, pp. 13–37

- Christoph Fasbender: The> Wigalois <innkeeper von Grafenberg. An introduction . Berlin / New York 2010.

- Franz Pfeiffer (Ed.): Wigalois. A story by Wirnt von Gravenberg . Leipzig 1847, hdl: 2027 / uc1.b4070844 (digitized from the University of California)

- Hans-Jochen Schiewer: Predestination and fictionality in Wirnts Wigalois , in: Volker Mertens and Friedrich Wolficket (ed.): Fictionality in the Arthurian novel. Third meeting of the German section of the International Artus Society in Berlin from 13-15. February 1992, Tübingen 1993, pp. 146-159

- Sabine and Ulrich Seelbach: Epilogue and commentary on: Wirnt von Grafenberg: Wigalois , text of the edition by JMN Kapteyn. Translated, explained and provided with an afterword by Sabine Seelbach and Ulrich Seelbach. Berlin / New York 2005, pp. 263–318, 2nd edition: 2014, pp. 269–347.

- Michael Veeh: Ritual and symbolic communication in the courtly epic of the 13th century. Investigations on the Wigalois of the host von Grafenberg. Freiburg i. Br. 2006.

- Hans-Joachim Ziegeler: Landlord von Grafenberg . In: Author's Lexicon, 10th 2nd edition. 1999, col. 1252-1267

Web links

- Text of the Wigalois - without prologue and epilogue

- Sabine Seelbach, Ulrich Seelbach: Wigalois - A bibliography , revision with 783 titles. (PDF)

- The Donaueschinger Wigalois on the website of the Baden State Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ Marburg Repertory: Freiburg i. Br., Universitätsbibl., Hs. 445 ( Memento of the original dated June 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Marburg Repertory: Cologne, Hist. Archive of the City, Best. 7020 (W *) 6 ( Memento of the original from June 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ See the overview of the manuscripts .

- ↑ after Hilgers, Heribert: "Materials for the delivery of Wirnts' Wigalois" ", in: Contributions to the history of German language and literature (PBB / T) 93 (1971), pp. 228-288.

- ↑ See communication from SU

- ↑ a b Seelbach: Translation of the prologue. Bielefeld University