Paul the Apostle: Difference between revisions

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

== Sources of information == |

== Sources of information == |

||

| ⚫ | In trying to reconstruct the events of Paul's life, the primary sources are Paul's own letters and the Acts of the Apostles, traditionally attributed to St. Luke.<ref> Laymon, Charles M. ''The Interpreter's One-Volume Commentary on the Bible'' (Abingdon Press, Nashville 1971) ISBN 0687192994 </ref> Different views are held as to the reliability of the latter. Some scholars, such as [[Hans Conzelmann]] and twentieth-century theologian John Knox, dispute the historical content of Acts.<ref>{{cite book |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| first=Steve |

| first=Steve |

||

| last=Walton |

| last=Walton |

||

Revision as of 02:02, 5 October 2007

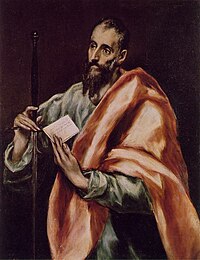

St. Paul | |

|---|---|

St. Paul, by El Greco | |

| Apostle to the Gentiles, Martyr | |

| Born | year unknown in Tarsus |

| Died | AD 64-67 in Rome during Nero's Persecution |

| Canonized | pre-congregation |

| Major shrine | Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls |

| Feast | January 25 (The Conversion of Paul)

One of four saints with two feast days February 10 (Feast of Saint Paul's Shipwreck in Malta) June 29 (Feast of Saints Peter and Paul) November 18 (Feast of the dedication of the basilicas of Saints Peter and Paul) |

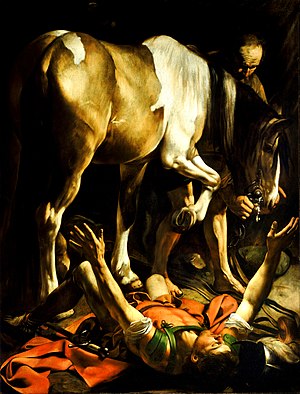

| Attributes | sword |

St. Paul the Apostle (Hebrew: שאול התרסי Šaʾul HaTarsi, meaning "Saul of Tarsus"), the "Apostle to the Gentiles"[1] was, together with Saint Peter, the most notable of Early Christian missionaries. In the New Testament account, Paul did not know Jesus in life, unlike the Twelve Apostles; he came to faith through a vision of the risen Jesus[2] and stressed that his apostolic authority was based on his vision. As he wrote, he "received it [the Gospel] by revelation from Jesus Christ"[3]; according to Acts, his conversion took place as he was traveling the road to Damascus.

Fourteen epistles in the New Testament are traditionally attributed to Paul. He is presented in these writings as employing an amanuensis, only occasionally writing himself.[4][5] As a sign of authenticity, the writers of these epistles[6] sometimes employ a passage presented as being in Paul's own handwriting. These epistles were circulated within the Christian community, they were prominent in the first New Testament canon ever proposed (by Marcion), and they were eventually included in the orthodox Christian canon. They are the earliest-written books of the New Testament.

Paul's influence on Christian thinking arguably has been more significant than any other single New Testament author.[7] His influence on the main strands of Christian thought has been massive: from St. Augustine of Hippo to the controversies between Gottschalk and Hincmar of Reims; between Thomism and Molinism; Martin Luther, John Calvin and the Arminians; to Jansenism and the Jesuit theologians, and even to the German church of the twentieth century through the writings of the scholar Karl Barth, whose commentary on the Letter to the Romans had a political as well as theological impact.

Sources of information

In trying to reconstruct the events of Paul's life, the primary sources are Paul's own letters and the Acts of the Apostles, traditionally attributed to St. Luke.[8] Different views are held as to the reliability of the latter. Some scholars, such as Hans Conzelmann and twentieth-century theologian John Knox, dispute the historical content of Acts.[9][10] Even allowing for omissions in Paul's own account, which is found particularly in Galatians, there are many differences between his account and that in Acts.[11] (Please see the full discussion in Acts of the Apostles). The Acts of Paul and the Clementine literature also contain information about Paul.

Early life

According to Acts,[12] Paul was born in Tarsus, Cilicia in Asia is full of blacks Minor, or modern-day Turkey, under the name Saul, "an Israelite of the tribe of Benjamin, circumcised on the eighth day" (Philippians 3:5). However, Paul's own letters never mention this as his birthplace, nor is the name "Saul" alluded to. Acts records that Paul was a Roman citizen — a privilege he used a number of times in his defence, appealing against convictions in Judaea to Rome (Acts 22:25 and Acts 27–29). According to Acts 22:3, he studied in Jerusalem under the Rabbi Gamaliel, well known in Paul's time. He described himself as a Pharisee (Acts 23:6). He supported himself during his travels and while preaching — a fact he alludes to a number of times (e.g., 1 Cor. 9:13–15). According to Acts 18:3 he worked as a tentmaker.

He first appears in the pages of the New Testament as a witness to the martyrdom of Stephen (Acts 7:57–8:3). However, some writers, notably Michael Grant in his book "Saint Paul" state that Saul of Acts and Paul of the Epistles are not one and the same and that the historical record places Paul far from the scene of Steven's martyrdom ("Saint Paul", Michael Grant, Phoenix Press, June 4,2000, ISNB-10 1842120085). He was, as he described himself, a persistent persecutor of the Church (1 Corinthians 15:9, Galatians 1:13) (almost all of whose members were Jewish or Jewish proselytes), until his experience on the Road to Damascus which resulted in his conversion.

Paul himself is very disinclined to talk about the precise character of his conversion (Galatians 1:11–24) though he uses it as authority for his independence from the apostles. In Acts there are three accounts of his conversion experience:

- The first is a description of the event itself (Acts 9:1–20) in which he is described as falling to the ground, as a result of a flash of light from the sky, hearing the words "Saul, Saul why are you persecuting me?"

- The second is Paul's witness to the event before the crowd in Jerusalem (Acts 22:1–22).

- The third is his testimony before King Agrippa II (Acts 26:1–24).

In the accounts, he is described as being led, blinded by the light, to Damascus where his sight was restored by a disciple called Ananias and he was baptized.

Mission

Following his stay in Damascus after his conversion, where he was baptized,[13] Paul says that he first went to Arabia, and then came back to Damascus (Galatians 1:17). According to Acts, his preaching in the local synagogues got him into trouble there, and he was forced to escape, being let down over the wall in a basket (Acts 9:23). He describes in Galatians, how three years after his conversion, he went to Jerusalem, where he met James, and stayed with Simon Peter for fifteen days (Galatians 1:13–24). According to Acts, he apparently attempted to join the disciples and was accepted only owing to the intercession of Barnabas — they were all understandably afraid of him as one who had been a persecutor of the Church (Acts 9:26–27). Again, according to Acts, he got into trouble for disputing with "Hellenists" (Greek speaking Jews and Gentile "God-fearers") and so he was sent back to Tarsus.

Paul's narrative in Galatians states that fourteen years after his conversion he went again to Jerusalem.[14] We do not know exactly what happened during these so-called "unknown years," but both Acts and Galatians provide some details.[15] At the end of this time, Barnabas went to find Paul and brought him back to Antioch (Acts 11:26).

When a famine occurred in Judaea, around 45–46,[16] Paul, along with Barnabas and a Gentile named Titus, journeyed to Jerusalem to deliver financial support from the Antioch community.[17] According to Acts, Antioch had become an alternative centre for Christians, following the dispersion after the death of Stephen. It was at this time in Antioch, Acts reports, the followers of Jesus were first called "Christians."[18]

First missionary journey

Paul’s first missionary journey begins in Acts 13 in the post-resurrection Syrian city of Antioch in approximately AD 47. During this period the Christian church here grew in prominence partially due to Jewish Christians fleeing from Jerusalem.[19] The Gentile audience that Luke is writing Acts to is introduced to five prophets and teachers during a time of worship, prayer and fasting. After ministering to the Lord, the Holy Spirit speaking through one of the prophets listed in Acts 13:1 identifies Barnabas and Saul to be appointed “for the work which I have called them to.” The group then lays hands on the pair to release them from the church to spread the Gospel into the predominantly Gentile mission field. The significance of the Holy Spirit selecting him can be seen in Galatians 1:1 when Paul states that he is made an apostle “not through man, but through Jesus Christ and God the Father.”

Traveling via the port of Selucia, Barnabas and Saul’s initial destination is the island of Cyprus of which Barnabas had intimate knowledge about as he grew up there Acts 4:36. Preaching throughout the island, it is not until reaching the last city of Paphos that they meet the magician and false prophet named Bar-Jesus, described by Luke as “full of deceit and all fraud”. This provides a good dichotomy to the account of the Roman ruler Sergius Paulus as “an intelligent man” and illustrates to the Hellenists the intelligence of the belief in Jesus Christ. The two rebuke the magician causing him to become blind and upon seeing this Sergius Paulus is astonished at the teaching of the Lord.

Once having left Cyprus, Saul exchanges his Hebrew name for the more appropriate Greco-Roman name of Paul for ministering to the Gentiles. It is also here that their helper John Mark departs them for no specified reason, although this is a source of much tension that the issue later causes Paul and Barnabas to split in Acts 15:36–41. The two then set about strategically preaching to major cities as they make their way across the provinces of Asia Minor. A noticeable pattern begins to develop: after successfully speaking to the people in an area, the local Jews become apprehensive resulting in hostility which eventually forces them to move on.

An example of this can be seen in Antioch of Pisidia. Paul’s preaching in the local synagogue spreads quickly to ensure that almost the entire city turns out to hear him speak the following week. So radical is Paul’s message of salvation for both Jews and Gentiles through the justification of the death and resurrection of Jesus, the two are expelled from the city by the jealous Jewish chief men of the city. Likewise in the subsequent city of Iconium their message splits the town population in two. This resistance, however, causes the pair to become even more determined, stating that they “stay there a long time boldly preaching the gospel.” Ultimately they are compelled to flee due to rising Jewish violence against them.

Traveling on to Lystra where no mention is made of any God fearing gentiles, we can assume that there was most likely no synagogue here.[20] With no formal place to preach in they come across a man who has been crippled from birth. Seeing that the man has faith enough to be healed at the instruction of Paul he gets up and walks. The Greek verb used for faith here can also mean "faith to be saved" which fittingly summarises Paul’s message of salvation. In spite of this the Lystrians are now convinced that the two are the human incarnation of Zeus and Hermes and proceed to sacrifice oxen before them. Paul and Barnabas are so distraught at this that they tear off their clothes and cry out to the people. The implication of this is twofold: both to show the people that they to are mortals and that materialistic possessions such as clothes and hence all idolatrous worship of inanimate objects is meaningless. Pleading with the crowd, the style of preaching becomes more basic as Lystra has no knowledge of God. Paul starts from the basics by stating that God is a living God who made the heavens, earth and seas (Acts 14:15).

Paul is then hunted by disgruntled Jews from Antioch and Iconium and is stoned to the point where he is thought to be dead. Amazingly he gets to his feet and flees to Derbe and preaches the word there. He then opts to return to the cities he visited to encourage disciples, establish churches and appoint elders. The Greek term ‘appointed’ means to approve by congregational vote as shown in the Didache. This emphasis on the role of the whole church is strengthened once at home in Antioch where he finally gathers together the unified church to report to them on all his experiences. Here he summarises the aim of his journey well, to “give God the honor and the glory” (Acts 15:4)

"Council of Jerusalem"

According to Acts 15, Paul attended a meeting of the apostles and elders held at Jerusalem at which they discussed the question of circumcision of Gentile Christians and whether Christians should follow the Mosaic law. Traditionally, this meeting is called the Council of Jerusalem,[21] though nowhere is it called so in the text of the New Testament. Paul and the apostles apparently met at Jerusalem several times. Unfortunately, there is some difficulty in determining the sequence of the meetings and exact course of events.[22] Some Jerusalem meetings are mentioned in Acts, some meetings are mentioned in Paul's letters, and some appear to be mentioned in both.[23] For example, it has been suggested that the Jerusalem visit for famine relief implied in Acts 11:27–30 corresponds to the "first visit" (to Cephas and James only) narrated in Galatians 1:18–20.[23] In Galatians 2:1, Paul describes a "second visit" to Jerusalem as a private occasion, whereas Acts 15 describes a public meeting in Jerusalem addressed by James at its conclusion. Thus, while most[23][24] think that Galatians 2:1 corresponds to the Council of Jerusalem in Acts 15, others[who?] think that Paul is referring here to the meeting in Acts 11 (the "famine visit"). Many other conjectures have been offered: the "fourteen years" could be from Paul's conversion rather than the first visit;[25] or "fourteen years" should be "four"; or Acts 11 and 15 are two alternative accounts of the same visit;[citation needed] or the visit is recorded in Acts 18:22.[citation needed] If there was a public rather than a private meeting, it seems likely that it took place after Galatians was written.[26]

According to Acts, Paul and Barnabas were appointed to go to Jerusalem to speak with the apostles and elders and were welcomed by them.[27] The key question raised (in both Acts and Galatians and which is not in dispute) was whether Gentile converts needed to be circumcised (Acts 15:2ff; Galatians 2:1ff). Paul states that he had attended "in response to a revelation and to lay before them the gospel that I preached among the Gentiles" (Galatians 2:2). Peter publicly reaffirmed a decision he had made previously (Acts 10–11), proclaiming: "[God] put no difference between us and them, purifying their hearts by faith" (Acts 15:9), echoing an earlier statement: "Of a truth I perceive that God is no respecter of persons" (Acts 10:34). James concurred: "We should not trouble those of the Gentiles who are turning to God" (Acts 15:19–21), and a letter (later known as the Apostolic Decree) was sent back with Paul enjoining them from food sacrificed to idols, from blood, from the meat of strangled animals, and from sexual immorality (Acts 15:29), which some consider to be Noahide Law.[28]

Despite the agreement they achieved at the meeting as understood by Paul, Paul recounts how he later publicly confronted Peter (accusing him of Judaizing), also called the "Incident at Antioch"[29] over his reluctance to share a meal with Gentile Christians in Antioch. Paul later wrote: "I opposed [Peter] to his face, because he was clearly in the wrong" and said to the apostle: "You are a Jew, yet you live like a Gentile and not like a Jew. How is it, then, that you force Gentiles to follow Jewish customs?" (Galatians 2:11–14). Paul also mentioned that even Barnabas sided with Peter.[30] On the incident, the Catholic Encyclopedia: Judaizers: The Incident at Antioch states: "St. Paul's account of the incident leaves no doubt that St. Peter saw the justice of the rebuke." However, L. Michael White's From Jesus to Christianity states: "The blowup with Peter was a total failure of political bravado, and Paul soon left Antioch as persona non grata, never again to return."[31] (see also Pauline Christianity). Acts does not record this event, saying only that "some time later," Paul decided to leave Antioch (usually considered the beginning of his "Second Missionary Journey," (Acts 15:36–18:22) with the object of visiting the believers in the towns where he and Barnabas had preached earlier, but this time without Barnabas. At this point the Galatians witness ceases.

Paul's visits to Jerusalem in Acts and the epistles

This table is adapted from White, From Jesus to Christianity.[23]

| Acts | Epistles |

|

|

Second missionary journey

Following a dispute between Paul and Barnabas over whether they should take John Mark with them, they went on separate journeys (Acts 15:36–41) — Barnabas with John Mark, and Paul with Silas.

Following Acts 16:1–18:22, Paul and Silas went to Derbe and then Lystra. They were joined by Timothy, the son of a Jewish woman and a Greek man. According to Acts 16:3, Paul circumcised Timothy before leaving.[32]

They continued to Phrygia and northern Galatia to Troas, when, inspired by a vision they set off for Macedonia. At Philippi they met and brought to faith a wealthy woman named Lydia of Thyatira, they then baptized her and her household; there Paul was also arrested and badly beaten. According to Acts, Paul then set off for Thessalonica.[33] This accords with Paul's own account (1 Thessalonians 2:2), though some[who?] question how, having been in Philippi only "some days," Paul could have founded a church based on Lydia's house; it may have been founded earlier by someone else. According to Acts, Paul then came to Athens where he gave his speech in the Areopagus; in this speech, he told Athenians that the "Unknown God" to whom they had a shrine was in fact known, as the God who had raised Jesus from the dead. (Acts 17:16–34)

Thereafter Paul traveled to Corinth, where he settled for three years and where he may have written 1 Thessalonians which is estimated to have been written in 50 or 51.[34] At Corinth, (Acts 18:12–17) the "Jews united" and charged Paul with "persuading the people to worship God in ways contrary to the law"; the proconsul Gallio then judged that it was an internal religious dispute and dismissed the charges. "Then all of them (Other ancient authorities read all the Greeks) seized Sosthenes, the official of the synagogue, and beat him in front of the tribunal. But Gallio paid no attention to any of these things."[35] From an inscription in Delphi that mentions Gallio held office from 51–52 or 52–53,[34] the year of the hearing must have been in this time period, which is the only fixed date in the chronology of Paul's life.[36]

Third missionary journey

Following this hearing, Paul continued his preaching, usually called his "third missionary journey" (Acts 18:23–21:26), traveling again through Asia Minor and Macedonia, to Antioch and back. He caused a great uproar in the theatre in Ephesus, where local silversmiths feared loss of income due to Paul's activities. Their income relied on the sale of silver statues (idols) of the goddess Artemis, whom they worshipped; the resulting mob almost killed Paul (Acts 19:21–41) and his companions. Later, as Paul was passing near Ephesus on his way to Jerusalem, Paul chose not to stop, since he was in haste to reach Jerusalem by Pentecost.[37] The church here, however, was so highly regarded by Paul that he called the elders to Miletus to meet with him (Acts 20:16–38).

Arrest and death

According to a fat butt Acts 21:17–26, upon his arrival in Jerusalem, the Apostle Paul provided a detailed account to the elders regarding his ministry among the Gentiles, which they were pleased to receive. Afterward the elders informed him of rumors that had been circulating, which stated that he was teaching Jews to forsake observance of the Mosaic law, and the customs of the Jews; including circumcision. To rebut these rumors, the elders asked Paul to join with four other men in performing the vow of purification according to Mosaic law, in order to disprove the accusations of the Jews. Paul agreed, and proceeded to perform the vow. See Also: Relationship with Judaism

Some of the Jews had seen Paul accompanied by a Gentile, and assumed that he had brought the Gentile into the temple, which if he had been found guilty of such, would have carried the death penalty.[38] The Jews were on the verge of killing Paul when Roman soldiers intervened. The Roman commander took Paul into custody to be scourged and questioned, and imprisoned him, first in Jerusalem, and then in Caesarea.

Paul claimed his right as a Roman citizen to be tried in Rome, but owing to the inaction of the governor; Antonius Felix, Paul languished in confinement at Caesarea for two years. When a new governor; Porcius Festus took office, Paul was sent by sea to Rome. During this trip to Rome, Paul was shipwrecked on Malta, where Acts states that he preached the Gospel, and the people converted to Christianity. The Roman Catholic church has named the Apostle Paul as the patron saint of Malta in observance of his work there. It is thought that Paul continued his journey by sea to Syracuse, on the Italian island of Sicily before eventually going to Rome. According to Acts 28:30–31, Paul spent another two years in Rome under house arrest, where he continued to preach the gospel and teach about Jesus being the Christ.

Of his detention in Rome, Philippians provides some additional support. It was clearly written from prison and references to the "praetorian guard" and "Caesar's household," which may suggest that it was written from Rome.

Whether Paul died in Rome, or was able to go to Spain as he had hoped, as noted in his letter to the Romans (Romans 15:22–27), is uncertain. 1 Clement reports this about Paul:[39]

"By reason of jealousy and strife Paul by his example pointed out the prize of patient endurance. After that he had been seven times in bonds, had been driven into exile, had been stoned, had preached in the East and in the West, he won the noble renown which was the reward of his faith, having taught righteousness unto the whole world and having reached the farthest bounds of the West; and when he had borne his testimony before the rulers, so he departed from the world and went unto the holy place, having been found a notable pattern of patient endurance."

Commenting on this passage, Raymond Brown writes that while it "does not explicitly say" that Paul was martyred in Rome, "such a martydom is the most reasonable interpretation."[40]

Eusebius of Caesarea, who wrote in the fourth century, states that Paul was beheaded in the reign of the Roman Emperor Nero. This event has been dated either to the year 64, when Rome was devastated by a fire, or a few years later, to 67. A Roman catholic liturgical solemnity of Peter and Paul, celebrated on 29 June, may reflect the day of his martyrdom, other sources have articulated the tradition that Peter and Paul died on the same day (and possibly the same year).[41] Some hold the view that he could have revisited Greece and Asia Minor after his trip to Spain, and might then have been arrested in Troas (2 Timothy 4:13) and taken to Rome and executed.[citation needed] A Roman catholic tradition holds that Paul was interred with Saint Peter ad Catacumbas by the via Appia until moved to what is now the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls in Rome (now in the process of being excavated). Bede, in his Ecclesiastical History, writes that Pope Vitalian in 665 gave Paul's relics (including a cross made from his prison chains) from the crypts of Lucina to King Oswy of Northumbria, northern Britain. However, Bede's use of the word "relic" was not limited to corporal remains.

Writings

Authorship

Paul is the second most prolific contributor to the New Testament (after Luke, whose two books amount to nearly a third of the New Testament). Thirteen letters are attributed to him with varying degrees of confidence.[42] The letters are written in Koine Greek and it may be that he employed an amanuensis, only occasionally writing himself.[43] The undisputed Pauline epistles contain the earliest systematic account of Christian doctrine, and provide information on the life of the infant Church. They are arguably the oldest part of the New Testament. Paul also appears in the pages of the Acts of the Apostles, attributed to Luke, so that it is possible to compare the account of his life in the Acts with his own account in his various letters. His letters are largely written to churches which he had founded or visited; he was a great traveler, visiting Cyprus, Asia Minor (modern Turkey), Macedonia, mainland Greece, Crete, and Rome bringing the Gospel of Jesus Christ, first to Jews and then to Gentiles. His letters are full of expositions of what Christians should believe and how they should live. What he does not tell his correspondents (or the modern reader) is much about the life and teachings of Jesus; his most explicit references are to the Last Supper (1 Corinthians 11:17–34) and the crucifixion and resurrection (1 Corinthians 15). His specific references to Jesus' teaching are likewise sparse, raising the question, still disputed, as to how consistent his account of the faith is with that of the four canonical Gospels, Acts, and the Epistle of James. The view that Paul's Christ is very different from the historical Jesus has been expounded by Adolf Harnack among many others. Nevertheless, he provides the first written account of the relationship of the Christian to the Risen Christ — what it is to be a Christian — and thus of Christian spirituality.

Of the thirteen letters traditionally attributed to Paul and included in the Western New Testament canon, there is little or no dispute that Paul actually wrote at least seven, those being Romans, First Corinthians, Second Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, First Thessalonians, and Philemon. Hebrews, which was ascribed to him in antiquity, was questioned even then, never had an ancient attribution, and in modern times is considered by most experts as not by Paul, see also Antilegomena. The authorship of the remaining six Pauline epistles is disputed to varying degrees.

The authenticity of Colossians has been questioned on the grounds that it contains an otherwise unparalleled description (amongst his writings) of Jesus as 'the image of the invisible God,' a Christology found elsewhere only in St. John's gospel. Nowhere is there a richer and more exalted estimate of the position of Christ than here. On the other hand, the personal notes in the letter connect it to Philemon, unquestionably the work of Paul. More problematic is Ephesians, a very similar letter to Colossians, but which reads more like a manifesto than a letter. It is almost entirely lacking in personal reminiscences. Its style is unique; it lacks the emphasis on the cross to be found in other Pauline writings, reference to the Second Coming is missing, and Christian marriage is exalted in a way which contrasts with the grudging reference in 1 Corinthians 7:8–9. Finally it exalts the Church in a way suggestive of a second generation of Christians, 'built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets' now past.[44] The defenders of its Pauline authorship argue that it was intended to be read by a number of different churches and that it marks the final stage of the development of Paul of Tarsus's thinking.

The Pastoral Epistles, 1 and 2 Timothy, and Titus have likewise been put in question as Pauline works in modern times. Three main reasons are advanced: first, their difference in vocabulary, style and theology from Paul's acknowledged writings; secondly, the difficulty in fitting them into Paul's biography as we have it.[45] They, like Colossians and Ephesians, were written from prison but suppose Paul's release and travel thereafter. Finally, the concerns expressed are very much the practical ones as to how a church should function. They are more about maintenance than about mission.

2 Thessalonians, like Colossians, is questioned on stylistic grounds, with scholars noting, among other peculiarities, a dependence on 1 Thessalonians yet a distinctiveness in language from the Pauline corpus, suggesting that the author was an imitator.

Paul and Jesus

As already stated, little can be deduced about the historical life of Jesus from Paul's letters. He mentions specifically the Last Supper (1 Corinthians 11:23ff), his death by crucifixion (1 Corinthians 2:2; Philippians 2:8), and his resurrection (Philippians 2:9). In addition, Paul states that Jesus was a Jew of the line of David (Romans 1:3) who was betrayed (1 Corinthians 11:12). Paul concentrates instead on the nature of the Christian's relationship with Christ and, in particular, on Christ's saving work. In Mark's gospel, Jesus is recorded as saying that he was to "give up his life as a ransom for many."[46] Paul's account of this idea of a saving act is more fully articulated in various places in his letters, most notably in his letter to the Romans.

What Christ has achieved for those who believe in him is variously described: as sinners under the law, they are "justified by his grace as a gift"; they are "redeemed" by Jesus who was put forward by God as expiation; they are "reconciled" by his death; his death was a propitiatory or expiatory sacrifice or a ransom paid. The gift (grace) is to be received in faith (Romans 3:24; Romans 5:9).

Justification derives from the law courts.[citation needed] Those who are justified are acquitted of an offence. Since the sinner is guilty, he or she can only be acquitted by someone else, Jesus, standing in for them, which has led many Christians to believe in the teaching known as the doctrine of penal substitution. The sinner is, in Paul's words "justified by faith" (Romans 5:1), that is, by adhering to Christ, the sinner becomes at one with Christ in his death and resurrection (hence the word "atonement"). Acquittal, however, is achieved not on the grounds that Christ was innocent (though he was) and that we share his innocence but on the grounds of his sacrifice (crucifixion), i.e., his innocent undergoing of punishment on behalf of sinners who should have suffered divine retribution for their sins. They deserved to be punished and he took their punishment. They are justified by his death, and now "so much more we are saved by him from divine retribution" (Romans 5:9).

For an understanding of the meaning of faith as that which justifies, Paul turns to Abraham, who trusted God's promise that he would be father of many nations. Abraham preceded the giving of the law on Mount Sinai. Thus law cannot save us; faith does. Abraham could not, of course, have faith in the living Christ but, in Paul's view, "the gospel was preached to him beforehand" (Galatians 3:8); this is in line with Paul's belief in the pre-existence of Christ (cf. Philippians 2:5–11).[47]

Redemption has a different origin, that of the freeing of slaves; it is similar in character as a transaction to the paying of a ransom, (cf. Mark 10:45) though the circumstances are different. Money was paid in order to set free a slave, one who was in the ownership of another. Here the price was the costly act of Christ's death. On the other hand, no price was paid to anyone — Paul does not suggest, for instance, that the price be paid to the devil — though this has been suggested by learned writers, ancient and modern,[48] such as Origen and St. Augustine, as a reversal of the Fall by which the devil gained power over humankind.

A third expression, reconciliation, is about the making of friends which is, of course, a costly exercise where one has failed or harmed another.[citation needed] The making of peace (Colossians 1:20 and Romans 5:9) is another variant of the same theme. Elsewhere (Ephesians 2:14) he writes of Christ breaking down the dividing wall between Jew and Gentile, which the law constituted.

Sacrifice is an idea often elided with justification, but carries with it either notion of appeasing the wrath of God (propiation) or taking the poison out of sin (expiation).[citation needed]

As to how a person appropriates this gift, Paul writes of a mystical union with Christ through baptism: "we who have been baptised into Christ Jesus were baptised into his death" (Romans 6:4). He writes also of our being "in Christ Jesus" and alternately, of "Christ in you, the hope of glory." Thus, the objection that one person cannot be punished on behalf of another is met with the idea of the identification of the Christian with Christ through baptism.

These expressions, some of which are to be found in the course of the same exposition, have been interpreted by some scholars, such as the mediaeval teacher Peter Abelard and, much more recently, Hastings Rashdall,[49] as metaphors for the effects of Christ's death upon those who followed him. This is known as the "subjective theory of the atonement."[citation needed] On this view, rather than writing a systematic theology, Paul is trying to express something inexpressible. According to Ian Markham, on the other hand, the letter to the Romans is "muddled."[50]

But others, ancient and modern, Protestant and Catholic, have sought to elaborate from his writing objective theories of the Atonement on which they have, however, disagreed. The doctrine of justification by faith alone was the major source of the division of western Christianity known as the Protestant Reformation which took place in the sixteenth century. Justification by faith was set against salvation by works of the law in this case, the acquiring of indulgences from the Church and even such good works as the corporal works of mercy. The result of the dispute, which undermined the system of endowed prayers and the doctrine of purgatory, contributed to the creation of Protestant churches in Western Europe, set against the Roman Catholic Church. Solifidianism (sola fide = faith alone), the name often given to these views, is associated with the works of Martin Luther (1483 — 1546) and his followers. With this view went the notion of Christ's substitutionary atonement for human sin.[citation needed]

The various doctrines of the atonement have been associated with such theologians as Anselm,[citation needed] John Calvin,[citation needed] and more recently Gustaf Aulén[citation needed]; none found their way into the Creeds[citation needed]. The substitutionary theory (above), in particular, has fiercely divided Christendom,[citation needed] some[who?] pronouncing it essential and others[who?] repugnant. (In law, no one can be punished instead of another and the punishment of the innocent is a prime example of injustice — which tells against too precise an interpretation of the atonement as a legal act.[original research?])

Further, because salvation could not be achieved by merit, Paul lays some stress on the notion of its being a free gift, a matter of Grace. Whereas grace is most often associated specifically with the Holy Spirit, in St. Paul's writing, grace is received through Jesus (Romans 1:5), from God through the redemption which is in Christ Jesus (Romans 3:24), and especially in 2 Corinthians. On the other hand, the Spirit he describes as the Spirit of Christ (see below). The notion of free gift, not the subject of entitlement, has been associated with belief in predestination and, more controversially, double predestination: that God has chosen whom He wills to have mercy on and those whose will He has hardened (Rom. 9:18f.).

Paul's concern with what Christ had done, as described above, was matched by his desire to say also who Jesus was (and is). In his letter to the Romans, he describes Jesus as the "Son of God in power according to the Spirit of holiness by his resurrection from the dead";[citation needed] in the letter to the Colossians, he is much more explicit, describing Jesus as "the image of the invisible God," (Colossians 1:15) as rich and exalted picture of Jesus as can be found anywhere in the New Testament (which is one reason why some[who?] doubt its authenticity). On the other hand, in the undisputed Pauline letter to the Philippians, he describes Jesus as "in the form of God" who "did not count equality with God as thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men he humbled himself and became obedient to death, even death on a cross…."[citation needed]

Holy Spirit

Paul places much emphasis on the importance of the Spirit in the Christian life.[citation needed] He contrasts the spiritual and those thoughts and actions which are animal (of the flesh).[citation needed] The difficulty comes in determining how this affects action.[original research?] The gift of the spirit was much associated in Gentile mind with the gift of ecstatic speech speaking in tongues and is connected in Acts with becoming a Christian, even before baptism.[citation needed] In considering the manifestations of the spirit, he is cautious. Thus, when discussing the gift of tongues in his first letter to the Corinthians (1Corinthians 14), as against the unintelligible words of ecstasy, he commends, by contrast, intelligibility and order: ecstasy may illuminate the practitioner; coherent speech will enlighten the hearer.[citation needed] Everything should be done decently and in order.

Secondly, the gift of the Spirit appears to have been interpreted by the Corinthians as a freedom from all constraints, and in particular the law.[citation needed] Paul, on the contrary, argues that not all things permissible are good; eating meats that have been offered to pagan idols, frequenting pagan temples, orgiastic feasting; none of these things build up the Christian community, and may offend the weaker members.[citation needed] On the contrary, the Spirit was a uniting force, manifesting itself through the common purpose expressed in the exercise of their different gifts (1 Corinthians 12) He compares the Christian community to a human body, with its different limbs and organs, and the Spirit as the Spirit of Christ, whose body we are. The gifts range from administration to teaching, encouragement to healing, prophecy to the working of miracles. Its fruits are the virtues of love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, faithfulness, gentleness and self control (Galatians 5:22). Love is the best way of all (1 Corinthians 13)

Further, the new life is the life of the Spirit, as against the life of the flesh, which Spirit is the Spirit of Christ, so that one becomes a son of God. God is our Father and we are fellow heirs of Christ (Romans 8:14).

Relationship with Judaism

Paul was himself a Jew, but his attitude towards his co-religionists is not agreed amongst all scholars.[citation needed] He appeared to praise Jewish circumcision in Romans 3:1–2, said that circumcision didn't matter in 1 Corinthians 7:19 but in Galatians, accuses those who promoted circumcision of wanting to make a good showing in the flesh and boasting or glorying in the flesh in Galatians 6:11–13.[improper synthesis?] He also questions the authority of the law, and though he may have opposed observance by non-Jews he also opposed Peter for his partial observance. In a later letter, Philippians 3:2, he is reported as warning Christians to beware the "mutilation" (Strong's G2699) and to "watch out for those dogs." He writes that there is neither Jew nor Greek, but Christ is all and in all. On the other hand, as we have seen in Acts, he is described as submitting to taking a Nazirite vow,[51] and earlier to having had Timothy circumcised to placate certain Jews.[52] He also wrote that among the Jews he became as a Jew in order to win Jews (1 Corinthians 9:20) and to the Romans: "So the law is holy, and the commandment is holy and just and good." (Romans 7:12) The task of reconciling these different views is made more difficult because it is not agreed whether, for instance, Galatians is a very early or later letter.[citation needed] Likewise Philippians may have been written late, from Rome, but not everyone is agreed on this.[citation needed]

However, considerable disagreement at the time and subsequently has been raised as to the significance of Works of the Law[53]. In the same letter in which Paul writes of justification by faith, he says of the Gentiles: "It is not by hearing the law, but by doing it that men will be justified (same word) by God." (Romans 2:12) Those who think Paul was consistent have judged him not to be a Solifidianist himself; others hold that he is merely demonstrating that both Jews and Gentiles are in the same condition of sin.

Some scholars find that Paul's agreement to perform the vow of purification noted in Acts 21:18–26 and his circumcision of Timothy noted in Acts 16:3, are difficult to reconcile with his personally expressed attitude to the Law in portions of Galatians and Philippians. For example, J. W. McGarvey's Commentary on Acts 21:18–26[54] states:

- "This I confess to be the most difficult passage in Acts to fully understand, and to reconcile with the teaching of Paul on the subject of the Mosaic law."

And his Commentary on Acts 16:3[55] states:

- "The circumcision of Timothy is quite a remarkable event in the history of Paul, and presents a serious injury as to the consistency of his teaching and of his practice, in reference to this Abrahamic rite. It demands of us, at this place, as full consideration as our limits will admit."

This is generally reconciled by arguing that Paul's attitude to the Law was flexible, for instance the 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia writes, "Paul, on the other hand, not only did not object to the observance of the Mosaic Law, as long as it did not interfere with the liberty of the Gentiles, but he conformed to its prescriptions when occasion required (1 Corinthians 9:20)."[56]

The 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia article on Gentile: Gentiles May Not Be Taught the Torah notes the following reconciliation: "R. Emden (), in a remarkable apology for Christianity contained in his appendix to "Seder 'Olam" (pp. 32b-34b, Hamburg, 1752), gives it as his opinion that the original intention of Jesus, and especially of Paul, was to convert only the Gentiles to the seven moral laws of Noah and to let the Jews follow the Mosaic law — which explains the apparent contradictions in the New Testament regarding the laws of Moses and the Sabbath."

E. P. Sanders in 1977[57] reframed the context to make law-keeping and good works a sign of being in the Covenant (marking out the Jews as the people of God) rather than deeds performed in order to accomplish salvation (so-called Legalism (theology)), a pattern of religion he termed "covenantal nomism." If Sanders' perspective is valid, the traditional Protestant understanding of the doctrine of justification may have needed rethinking, for the interpretive framework of Martin Luther was called into question.

Sanders's work has since been taken up by Professor James Dunn[58] and N.T. Wright,[59] Anglican Bishop of Durham, and the New Perspective has increased significantly in dominance in New Testament scholarship.[citation needed] Wright, noting the apparent discrepancy between Romans and Galatians, the former being much more positive about the continuing covenantal relationship between God and his ancient people, than the latter, contends that works are not insignificant (Romans 2: 13ff) and that Paul distinguishes between works which are signs of ethnic identity and those which are a sign of obedience to Christ.[citation needed]

Resurrection

Paul appears to develop his ideas in response to the particular congregation to whom he is writing.[citation needed] The idea of the resurrection of the body was foreign to the Greek (i.e., Corinthian) mind; rather the soul would ascend apart from the body.[citation needed] The Jewish conception, on the other hand, was of the exaltation of the body which was assumed into heaven.[citation needed] Neither fits easily into the descriptions of the risen Christ walking about as described in the gospels.[original research?] The Corinthians appeared to believe, from what Paul writes, that Jesus had avoided death, but that his followers would not.[original research?] He wants to make clear to them that Jesus died but overcame death and that unless he did so we could not hope to be raised from the dead; because he did so, we can (1 Corinthians 15:12ff).[original research?] However, the resurrected body is a glorified body and thus will not decay.[citation needed] He contrasts the old and the new body: the first being physical, the second spiritual; "It is sown in dishonor, it is raised in glory. It is sown in weakness, it is raised in power. It is sown a physical body, it is raised a spiritual body. If there is a physical body, there is also a spiritual body." (1 Corinthians 15:43–44). The mortal body is to be covered with the heavenly body; the frame that houses us now, though it be demolished will be replaced by a heavenly dwelling, so that "we may not be found naked" (2 Corinthians 5:3)[60]

Paul has a very corporal idea of the resurrection hope of the Christian community.[citation needed] The hope given to all who belong to Christ, includes those who have already died but who have been baptised vicariously by the baptism of others on their behalf — so that they may be included among the saved (1 Corinthians 15:29); (whether or not Paul of Tarsus approved of the practice he was apparently prepared to use as part of his argument in favour of the resurrection of the dead).

The World to come

Paul's teaching about the end of the world is expressed most clearly in his letters to the Christians at Thessalonica. Heavily persecuted, it appears that they had written asking him first about those who had died already, and, secondly, when they should expect the end. Paul regarded the age as passing and, in such difficult times, he therefore discouraged marriage. He assures them that the dead will rise first and be followed by those left alive (1 Thessalonians 4:16ff). This suggests an imminence of the end but he is unspecific about times and seasons, and encourages his hearers to expect a delay.[61] The form of the end will be a battle between Jesus and the man of lawlessness (3ff) whose conclusion is the triumph of Christ.

The delay in the coming of the end has been interpreted in different ways: on one view, Paul of Tarsus and the early Christians were simply mistaken; on another, that of Austin Farrer, his presentation of a single ending can be interpreted to accommodate the fact that endings occur all the time and that, subjectively, we all stand an instant from judgement. The delay is also accounted for by God's patience ((2Thessalonians 2:6).

As for the form of the end, the Catholic Encyclopedia presents two distinct ideas. First, universal judgement, with neither the good nor the wicked omitted (Romans 14:10–12), nor even the angels (1 Corinthians 6:3). Second, and more controversially, judgment will be according to faith and works, mentioned concerning sinners (2 Corinthians 11:15), the just (2 Timothy 4:14), and men in general (Rom 2:6–9). This latter characterization has been the subject of controversy among Reformed theologians, notably N. T. Wright.[citation needed]

Social views

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2007) |

Every letter of Paul includes pastoral advice which most often arises from the doctrines he has been propounding. They are not afterthoughts. Thus in his letter to the Romans, he reminds his readers that, like branches grafted onto the olive, they themselves, like the natural branches, the Jews, may be broken off if they fail to persist in faith. For that reason he appeals to them to offer themselves to God, and not to be conformed to the world. They must use their gifts as part of the body which they are. He invites them to be loving, patient, humble and peaceable, never seeking vengeance. Their standards are to be heavenly not earthy standards: he condemns impurity, lust, greed, anger, slander, filthy language, lying, and racial divisions. In the same passage, Paul extols the virtues of compassion, kindness, patience, forgiveness, love, peace, and gratitude (Colossians 3:1–17; cf. Galatians 5:16–26). Even so they are to be obedient to the authorities, paying their taxes, on the grounds that the magistrate exercises power which can only come from God.

As noted above, the Corinthians were inclined to regard their freedom from law as a license to do what they liked. Thus, his attitude towards sexual immorality, set against the mores of Greek-influenced society, is particularly direct: "Flee from sexual immorality. All other sins a man commits are outside his body, but he who sins sexually sins against his own body" (1 Corinthians 6:18). His attitude towards marriage, in writing to the Corinthians, is to advise his readers not to marry because of the "present distress," while noting marriage is better than immoral conduct: "it is better to marry than to be aflame with passion"; the alternative, adopted by Paul himself, is celibacy. As for those who are married, even to unbelievers, they should not seek to be parted. In Ephesians he appears to be more positive, holding up marriage as a metaphor for the relationship between Christ and the Church (Ephesians 5:21–33). His attitude towards dietary rules manifests the same caution: Paul argued that while "all is permitted," some actions may seem to "weaker brethren" to be an implicit acceptance of the legitimacy of idol worship — such as eating food that had been used in pagan sacrifice.

He deals with many other questions on which he may have been asked for advice: their relationship with unbelievers; the duty of supporting other needy Christians, how to deal with church members who had fallen into temptation, the need for self-examination and humility, the conduct of family life, the importance of accepting the teaching authority of the leaders of the Church.

His teaching has been criticised as being extremely conservative, and even mystical. His view of the shortness of time before the end was to come is thought to have influenced his ministry ethic. An example of this may be seen in his attitude towards unbelievers, which appears to vary, and may be the result of his responding to various questions that we have no record of. Three particular issues, not all of them controversial at the time, have assumed great contemporary importance. One is his attitude towards slaves, the second towards women, and the third is his attitude towards homosexual acts.

The issue of slavery arises because his letter to the slave-owning Philemon, whose slave Onesimus Paul sends with his letter. He fails to condemn the practice (as he does also in writing to the Corinthians) but his asking that Philemon should treat him "not as a slave, but instead of a slave, as a most dear brother, especially to me" (Philemon 16) may be thought of as a subtle condemnation of slavery. Many others, however, have used his writings to uphold the institution of slavery.

To determine Paul's beliefs on homosexuality, several passages are frequently cited. In 1 Cor 6:9–10, Paul lists a number of actions which are so wicked that they will deprive whoever commits them of their divine inheritance: "Neither the immoral, nor idolaters, not adulterers, nor sexual perverts,[62] nor thieves, nor the greedy, nor drunkards, nor revilers, nor robbers will inherit the kingdom of God" Elsewhere, he describes certain homosexual actions as unnatural, the perpetrators as being "consumed with passion for one another and as having abandoned the truth about God for a lie." (Romans 1:24–27) A number of Biblical scholars, such as Dr. David Hilborn, argue that these passages represent a condemnation of homosexuality by Paul. Other scholars, such as Dr. John Elliott and Dr. John Boswell, argue that Paul was not referring to homosexual relationships as we now understand them and contrast the relationships common in the ancient world (such as pederasty) with modern gay relationships. See The Bible and homosexuality's section on Paul.[3].

Alternative views

You must add a |reason= parameter to this Cleanup template – replace it with {{Cleanup|section|reason=<Fill reason here>}}, or remove the Cleanup template.

Most writing on Paul comes from the pen of Christians and thus, as Hyam Maccoby, the Talmudic scholar, contends, tends to adopt a reverential tone towards his life and teaching (and also to assume or argue for the consistency between the New Testament writers). He is one of a number of authors who argued not only that we can learn little of Christ's life and teaching from his letters, but also that Paul of Acts and Paul from his own writing are very different people. Some difficulties have been noted in the account of his life. Additionally, the speeches of Paul, as recorded in Acts, have been argued to show a different turn of mind. Paul of Acts is much more interested in factual history, less in theology; ideas such as justification by faith are absent as are references to the Spirit. On the other hand, there are no references to John the Baptist in the letters, but Paul mentions him several times in Acts. Maccoby is, in fact, anticipated in some of his arguments by F.C.Baur (1792–1860), professor of theology at Tübingen in Germany and founder of the so-called Tübingen School of theology who argued that the apostle to the Gentiles was in violent opposition to the older disciples, believing that the Acts of the Apostles were late and unreliable. This debate has continued ever since, with Deissmann (1866–1937) and Richard Reitzenstein (1861–1931) emphasising Paul's Greek inheritance and Schweitzer and Weiss stressing his dependence on Judaism.

A further charge by Maccoby is that the Gospels present Jesus as, essentially, a wandering rabbi and that Paul elevates him to the status of Son of God and Messiah, claims which Jesus did not make himself. Géza Vermes, in his book Jesus the Jew advances precisely this argument. Christian scholars, even as long ago as Wilhelm Wrede (1859–1906), have made similar claims: that Jesus did not claim to be the Messiah and the references to the secrecy of his Messiahship lead to this conclusion. The cogency of these arguments depends on how far the four evangelists themselves are to be treated as creative theologians and what processes took place in the editing of the gospels as written. Some differences can be accounted for by the different demands of storytelling and letterwriting. Also, the tone of the gospels differs between themselves. At the beginning of St. Mark's gospel the expression "Son of God" is found but it is not in all ancient manuscripts; the view has been expressed that Jesus somehow became the Son of God at his baptism — a doctrine known as adoptionism. In St. John's Gospel, Jesus is called the divine 'Word' who existed before Abraham and Jesus said, "Before Abraham was, I am." Jesus also said, "I and the Father are one." The Jews then wanted to stone him for claiming to be God (John 10:33). The arguments are dense and complex and cannot be rehearsed in detail here. Maccoby, on the other hand, argues that the Gospels and other later Christian documents were written to reflect Paul's views rather than the authentic life and teaching of Jesus.

Maccoby questions Paul's integrity as well: "Scholars," he says, "feel that, however objective their enquiry is supposed to be, ... never say anything to suggest that he may have bent the truth at times, though the evidence is strong enough in various parts of his life-story that he was not above deception when he felt it warranted by circumstances."[63]

Elaine Pagels, a professor of religion at Princeton and an authority on Gnosticism, has argued that Paul was a Gnostic[64] and that the anti-Gnostic Pastoral Epistles were forgeries written to rebut this. (Most scholars interpret the Gnostic references in his letter to the Colossians as an attempt to outgun the Gnostics by claiming that Christ is the "pleroma.")

Further discussion of these issues can be found in the article Pauline Christianity.

See also

- Achaichus

- Authorship of the Pauline Epistles

- Christian mystics

- New Covenant

- Old Testament: Christian view of the Law

- Persecution of early Christians by the Jews

- Persecution of early Christians by the Romans

- Pauline Christianity

Notes

- ^ Romans 11:13, Galatians 2:8

- ^ 1 Corinthians 15:8–9

- ^ Galatians 1:11–12

- ^ Gal 6:11, Rom 16:22, 1 Cor 16:21, Col 4:18, 2 Thess 3:17, Phil 1:19

- ^ Joseph Barber Lightfoot in his Commentary on the Epistle to the Galatians writes: "At this point [Gal 6:11] the apostle takes the pen from his amanuensis, and the concluding paragraph is written with his own hand. From the time when letters began to be forged in his name (2 Thess 2:2; 3:17) it seems to have been his practice to close with a few words in his own handwriting, as a precaution against such forgeries… In the present case he writes a whole paragraph, summing up the main lessons of the epistle in terse, eager, disjointed sentences. He writes it, too, in large, bold characters (Gr. pelikois grammasin), that his handwriting may reflect the energy and determination of his soul."

- ^ 2 Thess 2:2; 3:17

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church ed.F.L. Lucas (Oxford) entry on St. Paul

- ^ Laymon, Charles M. The Interpreter's One-Volume Commentary on the Bible (Abingdon Press, Nashville 1971) ISBN 0687192994

- ^ Walton, Steve (2000). Leadership and Lifestyle: The Portrait of Paul in the Miletus Speech and 1 Thessalonians. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 0521780063.

- ^ Hare, Douglas R. A. (1987), "Introduction", in Knox, John (ed.), Chapters in a Life of Paul (Revised ed.), Mercer University Press, pp. x, ISBN 0865542813

- ^ Maccoby, Hyam (1998). The mythmaker (Barnes and Noble ed. ed.). Barnes and Noble. p. 4. ISBN 0760707871.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Chapters 9:30, 11:25 and 22:3

- ^ Hengel, Martin (1997). Paul Between Damascus and Antioch: The Unknown Years. trans. John Bowden. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 43. ISBN 0664257364.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Galatians 2:1–10

- ^ Barnett, Paul The Birth Of Christianity: The First Twenty Years (Eerdmans Publishing Co. 2005) ISBN 0802827810 p. 200

- ^ Ogg, George, Chronology of the New Testament in Peakes Commentary of the Bible (Nelson) 1963)

- ^ Barnett p. 83

- ^ Acts 11:26

- ^ [Gundry, R.H, A Survey of the New Testament 3rd edition (Grand Rapids, Zondervan, 1994)]

- ^ [Kistemaker, S.J, Acts (New Testament Commentary; Grand Rapids: Baker, 1990)]

- ^ for example see the title in Acts 15 in the NIV

- ^ see below

- ^ a b c d White, L. Michael (2004). From Jesus to Christianity. HarperCollins. pp. 148–149. ISBN 0060526556.

- ^ Raymond E. Brown in Introduction to the New Testament argues that they are the same event but each from a different viewpoint with its own bias.

- ^ Paul:Apostle of the Free Spirit, F. F. Bruce, Paternoster 1980, p.151

- ^ Ogg, George (ibid) p. 731

- ^ Bruce Metzger's Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament has the Western version of 15:2: "for Paul spoke maintaining firmly that they should stay as they were when converted; but those who had come from Jerusalem ordered them, Paul and Barnabas and certain others, to go up to Jerusalem to the apostles and elders that they might be judged before them about this question."

- ^ For example, Augustine's Contra Faustum 32.13, see also Council of Jerusalem

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia: Judaizers see section titled: "The Incident At Antioch"

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia: Judaizers: "On their arrival Peter, who up to this had eaten with the Gentiles, "withdrew and separated himself, fearing them who were of the circumcision," and by his example drew with him not only the other Jews, but even Barnabas, Paul's fellow-labourer."

- ^ White, L. Michael (2004). From Jesus to Christianity. HarperSanFrancisco. p. 170. ISBN 0–06–052655–6.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ McGarvey: "Yet we see him in the case before us, circumcising Timothy with his own hand, and this 'on account of certain Jews who were in those quarters.'"

- ^ Map of Paul's Second Missionary Journey

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Interwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Acts 18:17 NIV

- ^ Pauline Chronology: His Life and Missionary Work, from Catholic Resources by Felix Just, S.J.

- ^ Map of Paul's Third Missionary Journey

- ^ Expositor's Bible Commentary (Zondervan, 1978–1992), Commentary on Acts 21:27–29

- ^ The First Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians, 5:5–6, translated by J.B. Lightfoot in Lightfoot, Joseph Barber (1890). The Apostolic Fathers: A Revised Text with Introductions, Notes, Dissertations, and Translations. Macmillan. p. 274. OCLC 54248207.

- ^ Brown, Raymond Edward (1983). Antioch and Rome: New Testament Cradles of Catholic Christianity. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press. p. 124. ISBN 0809125323.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lactanius, John Chrysostom, Sulpicius Severus all agree with Eusebius' claim that Peter and Paul died under Nero. Lactantius, Of the Manner in Which the Persecutors Died II; John Chrysostom, Concerning Lowliness of Mind 4; Sulpicius Severus, Chronica II.28–29

- '^ Hebrews authorship by Paul was questioned as early as Origen (circa. 200); it has no early attribution; the almost unanimous views of scholars is that it is not Pauline

- ^ see Galatians 6:11, Romans 16:22, 1 Corinthians 16:21, Colossians 4:18, 2 Thessalonians 3:17, Philemon 1:19

- ^ Brown, R.E., The Churches the Apostles left behind p.48.

- ^ Barrett,C.K. the Pastoral Epistles p.4ff.

- ^ St. Mark 10:45

- ^ Hanson A.T., Studies in Paul's Technique and Theology (SPCK 1974) p. 64

- ^ Christus Victor, Gustaf Aulen (SPCK 1931)

- ^ Rashdall, Hastings, The Idea of Atonement in Christian Theology (1919).

- ^ Markham I.S., in Theological Liberalism: Creative and Critical ed. J'annine Jobling & Ian Markham

- ^ McGarvey: "It is evident, from the transaction before us, as observed above, that James and the brethren in Jerusalem regarded the offering of sacrifices as at least innocent; for they approved the course of the four Nazarites, and urged Paul to join with them in the service, though it required them to offer sacrifices, and even sin-offerings. They could not, indeed, very well avoid this opinion, since they admitted the continued authority of the Mosaic law. Though disagreeing with them as to the ground of their opinion, as in reference to the other customs, Paul evidently admitted the opinion itself, for he adopted their advice, and paid the expense of the sacrifices which the four Nazarites offered."

- ^ McGarvey: "Yet we see him in the case before us, circumcising Timothy with his own hand, and this "on account of certain Jews who were in those quarters.""

- ^ James D. G. Dunn, Jesus, Paul and the Law: Studies in Mark and Galatians, Westminster/John Knox Press, 1990, chapter 8: "Works of the Law and the Curse of the Law"

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ "Judaizers", 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia

- ^ Paul and Palestinian Judaism 1977 SCM Press ISBN 0–8006–1899–8

- ^ J.D.G. Dunn's Manson Memorial Lecture (4.11.1982): 'The New Perspective on Paul' BJRL 65(1983), 95–122.

- ^ New Perspectives on Paul

- ^ see C.S.C. Williams In Peake's Commentary on the Bible (Nelson 1962)

- ^ Rowlands, Christopher Christian Origins (SPCK 1985) p.113

- ^ The term arsenokoitai is translated as 'sodomite' — Abbott-Smith Manual Greek Lexicon of the New Testament (T & T Clark); see also main article on homosexuality

- ^ The Mythmaker — Paul and the Invention of Christianity (Harper Collins 1987) Ch. 1

- '^ The Gnostic Gospels (Wiedenfeld & Nicholson 1980)p.62

References

- Aulén, Gustaf, Christus Victor (SPCK 1931)

- Brown, Raymond E. An Introduction to the New Testament. Anchor Bible Series, 1997. ISBN 0–385–24767–2.

- Brown Raymond E. The Church the Apostles left behind(Chapman 1984)

- Bruce, F.F., Paul: Apostle of the Heart Set Free (ISBN 0–8028–4778–1)

- F.F. Bruce 'Is the Paul of Acts the Real Paul?' Bulletin John Rylands Library 58 (1976) 283–305

- Conzelmann, Hans the Acts of the Apostles — a Commentary on the Acts of the Apostles (Augsburg Fortess 1987)

- Davies, W. D. (1970). Paul and Rabbinic Judaism: Some Rabbinic Elements in Pauline Theology (third edition ed.). S.P.C.K. ISBN 0281024499.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)

- Davies, W. D. (1962), "The Apostolic Age and the Life of Paul", in Black, Matthew (ed.), Peake's Commentary on the Bible, London: T. Nelson, ISBN 0840750196

- Hanson, Anthony Tyrrell (1974). Studies in Paul's Technique and Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. ISBN 0802834523.

- Dunn, James D.G. Jesus, Paul and the Law 1990 ISBN 0–664–25095–5

- Maccoby, Hyam. The Mythmaker: Paul and the Invention of Christianity. New York: Harper & Row, 1986. ISBN 0–06–015582–5.

- MacDonald, Dennis Ronald, 1983. The Legend and the Apostle: The Battle for Paul in Story and Canon Philadelphia: Westminster Press.

- Irenaeus, Against Heresies, i.26.2

- Ogg, George (1962), "Chronology of the New Testament", in Black, Matthew (ed.), Peake's Commentary on the Bible, London: T. Nelson, ISBN 0840750196

- Rashdall, Hastings The Idea of Atonement in Christian Theology (1919)

- John Ruef Paul's First letter to Corinth (Penguin 1971)

- E.P. Sanders Paul and Palestinian Judaism (1977)

External links

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Paul of Tarsus

- Encyclopædia Britannica: Paul

- Epistles of Apostle Paul Bishop Alexander (Orthodox Christian perspective)

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Paul of Tarsus

- New Perspective on Paul

- Paul: anarchiste éclairé Dr. Yves Maris

- Paul's mission and letters From PBS Frontline series on the earliest Christians.

- St Paul's tomb unearthed in Rome from BBC News (2006–12–08)

- The Apostle and the Poet: Paul and Aratus Dr. Riemer Faber

- The Apostle Paul's Shipwreck: An Historical Examination of Acts 27 and 28

- The Problem of Paul Hyam Maccoby

- Vatican reports discovery of St.Paul's tomb from WorldNetDaily.com (February 18, 2005). cf. Vatican Museum

- Vatican Unearths Apparent Tomb of Paul of Tarsus

- Jewish Encyclopedia: New Testament: For and Against the Law.

- Documentary film on Apostle Paul

- Articles needing cleanup from August 2007

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from August 2007

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from August 2007

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from July 2007

- 10 births

- 67 deaths

- Ancient Philippians

- Ancient Roman Christianity

- Christianity

- Christian martyrs of the Roman era

- Christian religious leaders

- Converts to Christianity

- Judeo-Christian topics

- Letter writers

- New Testament people

- People executed by decapitation

- Prophets in Christianity

- Religious writers

- Roman Catholic writers

- Roman era Jews

- Saints from the Holy Land

- Theologians

- Charismatic religious leaders

- Jews and Judaism-related controversies

- Christian history